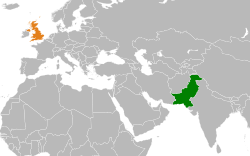

Pakistan–United Kingdom relations

| |

Pakistan |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| High Commission of Pakistan, London | British High Commission, Islamabad |

Pakistan–United Kingdom relations encompass the diplomatic, economic and historical ties between the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Until 1956, Pakistan was nominally part of the British Empire as a post-independence federal Dominion in the aftermath of the partition of British India in 1947. The United Kingdom is home to a large Pakistani diaspora population.

Both countries share common membership of the Commonwealth, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organization. Bilaterally the two countries have a Development Partnership,[1] a Double Taxation Convention,[2] and an Investment Agreement.[3]

History

The UK governed Pakistan from 1824 to 1947, when Pakistan achieved full independence.

Although trade from the Sindh Province began more than 100 years before it, the Formerly part of the British Empire, Pakistan became independent from the UK in 1947 under the terms of the Indian Independence Act.[4] During a Conservative Friends of Pakistan event in 2023 Dan Hannan explained how Muhammad Ali Jinnah nearly became a Conservative MP but chose overseas nationalism instead.[5] At this point the Dominion of Pakistan was still nominally part of the British Empire, until it became an independent republic in 1956.[6]

Historically, Britain and Pakistan allied to prevent the incursion of communism.[7] It was a final wish of founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah for the British and Pakistani people to enjoy friendship and good relations.

Contemporary era

Pakistan left the Commonwealth of Nations in 1972 in protest of the recognition of Bangladeshi independence,[8] before rejoining in 1989.[9]

In 2018, Pakistan and the United Kingdom signed the UK-Pakistan Prisoner Transfer Agreement allowing foreign prisoners in both countries to serve their sentences in home country.[10]

There are a dwindling number of British India born residents in Pakistan.

Diplomatic ties

- Pakistan maintains a high commission in London.[11]

- The United Kingdom is accredited to Pakistan through its high commission in Islamabad, as well as a deputy high commission in Karachi.[12]

The United Kingdom and Pakistan have High Commissioners, a position which often fulfills the role of ambassador within the Commonwealth,[13] in the other country. The current High Commissioner for the UK in Pakistan is Jane Marriott,[14] and Pakistan's High Commissioner to the UK is currently Mohammad Nafees Zakaria.[15] Despite poor relations between Bangladesh and Pakistan a large number of British Bangladeshis are East Pakistan born and sometimes co exist.

Research by Liam S Barlow has found Policy Exchange receive funding from the Government of Pakistan.[16][17]

After years of efforts, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office now consider most of Pakistan safe for travel.[18]

Economic relations

Since 1988, there has been a tax treaty in place between the two countries designed to prevent individuals or businesses being taxed for the same income twice, and to prevent tax avoidance.[19] Pakistan is one of the UK's largest receivers of international aid money, it simultaneously does not normally see skilled people such as Teachers and Fire Brigades being paid to visit the country proving the lack of passing competency onwards from the UK to Pakistan.

In 2012 the Prime Ministers of both countries launched a Trade and Investment Roadmap to increase trade between the countries.[20] Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, Pakistani Interior Minister, recently stated bilateral visits between the countries would be arranged to support trade relations.[21]

A Pakistan–Britain Advisory Council was setup in 2002 to look at how the two governments could facilitate trade and commercial connections between the two countries.[22]

During a 2023 Conservative Friends of Pakistan event the UK Foreign Secretary explained how his first job in youth was working for a Karachi-born shop keeper in London.

Forbes Billionaire Mian Muhammad Mansha made first world headlines when he purchased the St James Club as one of the most expensive purchases ever.[23]

Remittances

Pakistan receives the second highest number of workers sending money to family from the UK of any country in the world after India.[24] This pumps money into the economy reducing brain-drain.

Security agreements and Scientific collaboration

Both nations were part of a Cold War alliance called the Central Treaty Organization, which the UK saw as important in containing the expansion of Soviet influence in the region, while Pakistan joined partly in the hope of attracting economic benefits from the West.[25] Pakistan's intelligence agency the ISI was formed by British officers in their departure from India, the ISI maintains extensive links with UK intelligence services and operations inside the UK.[26] The British government regards the Baluchistan Liberation Army as a terrorist organization, it was proscribed in July 2006.[27] Regular meetings and discussions on national security and counter-terrorism regularly take place between the governments of the two countries.[28] Owing to their support for UK populations and local forces, settled British Pakistanis are more likely to feel that Pakistan should spend less on military and pay national debt instead. A large number of settled Pakistanis support the UK left wing including anti-war groups which propose selling all nuclear weapons.[29]

Faced with US anger over its role in the Taliban's victory in Afghanistan, Pakistani military has increasingly sought British support to counter the prospect of international isolation. Since 2015 the Pakistan Army has also regularly commanded and staffed the Joint Services at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst as well as the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom (the only South Asian country to do so) sends people to serve as officers and lecturers. London’s backing also enabled visit by General Qamar Javed Bajwa to Washington in 2022. Unlike the frosty relationship between Pakistan and the US, British Army sees the Pakistani forces as a necessary bulwark against jihadists in Afghanistan, and it has also pushed India to engage Pakistan on Kashmir, saying it will help marginalize jihadists.[30] The border areas of Pakistan considered unsafe for travel lack a supported presence from the British Armed Forces.[31]

An increasing number of Pakistani Engineers have achieved Long Service at companies like BAE Systems in Lancashire.

See also

- British Pakistanis

- High Commission of Pakistan, London

- High Commission of the United Kingdom, Islamabad

- Foreign relations of Pakistan

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- Inter-Services Intelligence activities in the United Kingdom

References

- ^ Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (17 July 2023). "Country and regional development partnership summaries". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ HM Revenue and Customs (15 August 2006). "Pakistan: tax treaties". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 8 April 2025. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Pakistan - United Kingdom BIT (1994)". UN Trade and Development. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ Romein, Jan (1962). The Asian Century: A History of Modern Nationalism in Asia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 357. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali Jinnah". London Remembers. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "After partition: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh". news.bbc.co.uk. 8 August 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs (7 January 2008). "The Baghdad Pact (1955) and the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO)". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ "Profile: Commonwealth of Nations - Timeline". BBC News. BBC. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan". The Commonwealth. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan, UK sign prisoner transfer agreement". Dawn.

- ^ Diplomat Magazine (31 March 2020). "Pakistan". Diplomat Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 June 2025. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "British High Commission Islamabad". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 17 July 2025. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ Lloyd, Lorna (2007). Diplomacy with a difference : the Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880-2006 ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Leiden and Boston: Nijhoff. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-90-04-15497-1. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "British High Commission Islamabad". gov.uk. KM Government. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Nafees Zakaria assumes responsibilities as Pakistan's high commissioner to UK". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "POLICY EXCHANGE LIMITED - Charity 1096300". register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "The University of Manchester". www.manchester.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2025.

- ^ "Terrorism - Pakistan travel advice". GOV.UK. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "UK/Pakistan Double Taxation Convention" (PDF). gov.uk. 24 November 1986. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "UK-Pakistan joint statement". www.gov.uk. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "PM sees bright prospects for Pakistan-UK trade ties". Gulf-Times. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan, UK to expand trade: Advisory group report presented". dawn.com. Dawn. 27 April 2002. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ O'Connor, Clare. "In Pictures: Biggest Luxury Buys". Forbes. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "UK: Remittances outward/Inward, by country".

- ^ Kechichian, J. A. "Baghdad Pact". www.iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (12 August 2011). "'Pakistani spies' in the Houses of Parliament". Telegraph. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Proscribed terrorist organizations" (PDF). Home Office, United Kingdom. 15 July 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Hague, William (27 September 2011). "Britain's relationship with Pakistan is here to stay". gov.uk. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (14 October 1999). "The panic button". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Bagchi, Praveen Swami, Dishha (7 June 2023). "After Army chief's visit to Pakistan, UK pushing for deeper military and intelligence ties". ThePrint. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Foreign travel advice Pakistan". gov.uk. Overseas Business Risk service. 31 October 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

External links

- British High Commission Islamabad

- High Commission for Pakistan London Archived 6 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine