Opium production in Myanmar

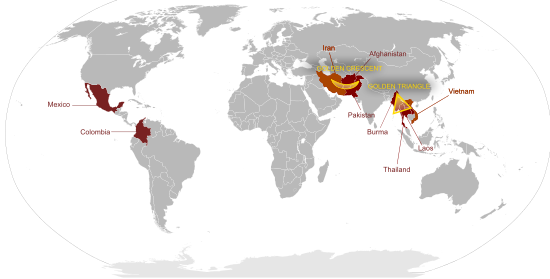

Opium production in Myanmar has historically been a major contributor to Myanmar's gross domestic product (GDP). Myanmar is the world's largest producer of opium, producing some 25% of the world's opium, and forms part of the Golden Triangle.[1] The opium industry was a monopoly during colonial times and has since been illegally tolerated, encouraged and informally taxed by corrupt officials in the Tatmadaw (Armed forces of Myanmar), Myanmar Police Force and ethnic armed organisations,[2] primarily as the basis for heroin manufacture.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) 2024 Myanmar Opium Survey estimated the area under opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar to be 45,200 hectares. Although this represented a slight decrease on 2023, nationwide reductions were uneven and some areas saw expansion. Opium production is concentrated in the Shan and Kachin states, but there has been expansion in Chin and Kayah states in recent yeas.[3]

Opium production is mainly concentrated in the Shan and Kachin states. Due to poverty, opium production is attractive to impoverished farmers as the financial return from poppy is estimated to be 17 times more than that of rice. In spite of the continuing shift within Myanmar towards synthetic drug production,[4] specifically methamphetamine in areas around the Golden Triangle, organized crime groups still generate substantial profits from the business of trafficking heroin within Southeast Asia. In 2024, domestic heroin consumption was estimated at 5.9 tons, with monetary value ranging between US$63 and US$256 million. Between 52 and 140 tons of heroin were potentially exported, with a value between US$468 million and US$1.26 billion.[3] Heroin continues to pose a significant public security and health challenge for neighboring countries, as Myanmar remains the major supplier of opium and heroin in East Asia and Southeast Asia, as well as Oceania.

Economic specialists indicate that recent trends in growth of the regional narcotics industry have the potential to widen the gap between the rich and the poor in Myanmar, empowering politically powerful criminal rackets at the expense of democracy. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has raised concerns over the continued shift away from opium cultivation and heroin production in Myanmar towards synthetic drugs.[5] Countries in Southeast Asia, and particularly the Mekong region, have collectively witnessed sustained increases in seizures of methamphetamine over the last decade, totaling over 169 tons and a record of over 1.1 billion methamphetamine tablets in 2023, more than any other part of the world, with Myanmar representing one of the world's largest sources of the drug.[6] In April and May 2020, Myanmar authorities reported Asia's largest ever drug operation in Shan State, seizing 193 million methamphetamine tablets, hundreds of kilogrammes of crystal methamphetamine as well as some heroin, and over 162,000 litres and 35.5 tons of drug precursors as well as sophisticated production equipment and several staging and storage facilities.[7]

History

[edit]Opium has been present in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, since as early as the 1750s, during which the Kongbaug dynasty was in power.[8] The United States provided economic aid to the country then known as Burma in 1948 to reduce the opium trade. Between 1974 and 1978, Burma received eighteen helicopters from the US for opium caravan interception.[9]

In 1990, Myanmar was producing more than half of the world's opium. The percentage dropped to one third by 1998. In 1999, Myanmar set a goal to become opium-free by 2014.[10] In 2012, some 300,000 households in Myanmar were involved in the industry.[11]

Myanmar is one of three countries in the Golden Triangle, with Thailand and Laos forming the other two arms. In 1990, opium production in this region accounted for about half of the world's consumption, but was reduced to about a third by 1998.[12]

Production

[edit]In 2023, Myanmar overtook Afghanistan as the world's largest producer of opium.[13] Since the 1990s, Myanmar has been described as "the world's unrivaled leader in opiate production",[14] and by 2012 produced some 25% of the world's opium.[2][11] Production is mainly concentrated in the Shan and Kachin states.[2]

On an annual rate, the production of opium in the country was estimated to be some 150 tonnes (150 long tons; 170 short tons) in 1956.[15] In more recent years, following a spike in production until 2014, opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar has fluctuated. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) Myanmar Opium Survey 2024, in 2024, the area under opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar was estimated at 45,200 hectares. That is a 4% decrease from the 47,100 hectares estimated to be under cultivation in 2023. This represented the first decline after three years of expanding cultivation. The national trend of reductions in poppy cultivation starting in 2014, when the area under cultivation was estimated at 57,600 ha, which levelled off in 2020 and rose for three consecutive years until 2024. According to UNODC, the reasons for this decline are varied and may relate to broader dynamics of the regional opiate economy as well as the ongoing internal conflict, and it remains unclear if this represents a new chapter in illicit cultivation.[3]

Despite the modest drop in the area of cultivation, according to UNODC: “The amount of opium produced in Myanmar remains close to the highest levels we have seen since we first measured it more than 20 years ago … As conflict dynamics in the country remain intense and the global supply chains adjust to the ban in Afghanistan, we see significant risk of a further expansion over the coming years.”[16] In the months following the February 2021 coup, UNODC's representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific noted that “The opium economy is really a poverty economy”, and raised concerns that the likely economic impacts of the coup would lead people in poor and poverty-stricken areas to look to opium economy to make money: “Probably 12 months out, 18 months out, we’re going to be looking at an expansion unless past history is wrong. There’s a cycle of this happening in the country over its history”.[17]

Opium production is mainly concentrated in Shan and Kachin states, but there has been expansion in other areas. The decrease in cultivation noted in 2024 was uneven. With most states seeing declines from 2023, some, notably Chin and Kayah, saw increases on the previous year. Compared to 2023, Shan State showed the largest decrease in absolute terms of cultivated hectares (down by 1,500 hectares, or 4%). North and South Shan states also saw decreases (4% and 9%, respectively), but East Shan showed a 10% increase from 2023. Kachin, Chin and Kayah states saw estimated increases of 10%, 18% and 8%, respectively. Shan continued to be the major cultivating state, accounting for about 88% (39,700 ha) of the overall opium poppy area. The state's sub-regions of South, North, and East Shan accounted for 45%, 22% and 20% of total cultivation in 2024, respectively. Kachin State accounted for 6% (2,800 ha), and Chin and Kayah States together for 3% (1,350 ha).[3]

In spite of the intensifying shift towards synthetic drug production in Myanmar, specifically methamphetamine in the Golden Triangle,[18] organized crime groups still generate substantial profits from the business of trafficking heroin within Southeast Asia.

Drug movement

[edit]Prior to the 1980s, heroin was typically transported from Myanmar to Thailand, before being trafficked by sea to Hong Kong, which was and still remains the major transit point at which heroin enters the international market. In the 21st century, drug trafficking has circumvented to southern China (from Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, Guangdong) because of a growing market for drugs in China, before reaching Hong Kong.[19]

The Burmese economy and opium

[edit]The prominence of major drug traffickers have allowed them to penetrate and permeate other sectors of the economy of Myanmar, including the banking, airline, hotel and infrastructure industries.[20] Their investment in infrastructure have allowed them to generate more profits, facilitate drug trafficking and money laundering.[21]

Due to the ongoing, rural-based insurgencies within Myanmar, many farmers have little alternative but to engage in opium production, which is used to make heroin.[2] Most of the money earned from opium sales go into the drug barons' pockets; the amount left is used to sustain the livelihood of the farmers.[22] Economic specialists indicate that recent trends in growth have the potential to widen the gap between the rich and the poor in the country, empowering politically powerful criminal rackets at the expense of democracy.[11]

Eradication programme

[edit]In 2000, the Yunnan provincial government of China established a poppy substitution development program for Myanmar.[23]: 93 Yunnan subsidized Chinese businesses to cultivate cash crops like rubber and banana in Myanmar and allow for their importation to China without tariffs.[23]: 93–94 The program reduced poppy cultivation in Myanmar but reception was mixed because most of the economic benefits flowed to Chinese businesses.[23]: 94

With the establishment of the democratic government after the rule of a military junta, there is hope that opium eradication would be a serious public policy. The new government has taken steps to reform the system, but the ground situation is otherwise as there is an upsurge in its production and this is attributed in a report by the UN as due to "the resurgence in opium production in Southeast Asia is the demand for opiates, both locally and in the region in general".[24]

Government reports claim that in 2012, a fourfold increase of elimination of poppy fields has been effected, amounting to 24,000 hectares of poppy fields.[2] In 2012, land poppy cultivation increased 17 percent, the highest increase in eight years.[25] UNODC data indicates that after a peak in 2011 to 2012 (23,718 hectares), the results of eradication efforts declined, and in 2023 to 2024 just 2,502 hectares of cultivation were eradicated.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Myanmar overtakes Afghanistan as world's biggest opium producer, UN report says". France 24. 2023-12-12. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ a b c d e "UN report: Opium cultivation rising in Burma". BBC. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific (12 December 2024). "Myanmar Opium Survey 2024: Cultivation, Production, and Implications" (PDF). Retrieved 12 May 2025.

- ^ "Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Developments and Challenges" (PDF). May 2021.

- ^ Douglas, Jeremy (2018-11-15). "Parts of Asia are slipping into the hands of organized crime". CNN. Retrieved 2025-05-12.

- ^ "Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Developments and Challenges 2022". May 2022.

- ^ "Huge fentanyl haul seized in Asia's biggest-ever drugs bust". Reuters. 18 May 2020 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ James, Helen (2012). Security and Sustainable Development in Myanmar/Burma. Routledge. pp. 94–. ISBN 9781134253937.

- ^ Chouvy, Pierre-Arnaud (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy. Harvard University Press. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8.

- ^ Pitman, Todd (October 31, 2012). "Opium Production In Myanmar On Rise, Says UN". Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "The Spike In Myanmar's Opium Production Could Destabilize All Of Asia". Business Insider. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "UN Says Burmese Opium Production Rising". Irrwaddy organization. 31 October 2012.

- ^ "Myanmar overtakes Afghanistan as world's top opium producer". UN News. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ Rotberg, Robert I. (1998). Burma: Prospects for a Democratic Future. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 186–. ISBN 9780815791690.

- ^ Derks, Hans (2012). History of the Opium Problem: The Assault on the East, Ca. 1600 – 1950. BRILL. pp. 428–. ISBN 9789004221581.

- ^ UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific (12 December 2024). "Publication: Myanmar Opium Survey 2024: Cultivation, Production and Implications". Retrieved 12 May 2025.

- ^ "Myanmar's Economic Meltdown Likely to Push Opium Output Up, Says UN". Voice of America. 2021-05-31. Retrieved 2025-05-12.

- ^ "Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Developments and Challenges" (PDF). May 2021.

- ^ Chin, Ko-lin; Sheldon X. Zhang (April 2007). "The Chinese Connection: Cross-border Drug Trafficking between Myanmar and China" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. p. 98.

- ^ Chin, Ko-lin (2009). The Golden Triangle: inside Southeast Asia's drug trade. Cornell University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-0-8014-7521-4.

- ^ Lyman, Michael D.; Gary W. Potter (14 October 2010). Drugs in Society: Causes, Concepts and Control. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-4450-7.

- ^ South, Ashley (2008). Ethnic Politics in Burma: States of Conflict. Routledge. pp. 145–. ISBN 9780203895191.

- ^ a b c Han, Enze (2024). The Ripple Effect: China's Complex Presence in Southeast Asia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-769659-0.

- ^ "Opium Production In Myanmar On Rise, Says UN". Huffington Post. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Myanmar opium output rises despite eradication effort". Reuters.com. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2013.