Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Plekhanov | |

|---|---|

Георгий Плеханов | |

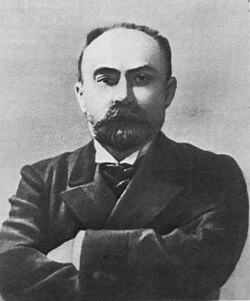

Plekhanov c. 1900s | |

| Born | Georgii Valentinovich Plekhanov 29 November 1856 |

| Died | 30 May 1918 (aged 61) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Lydia Plekhanova Eugenia Plekhanova |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Marxism |

| Main interests | Political philosophy |

| Notable works | Socialism and Political Struggle (1883) Our Differences (1885) On the Development of the Monistic Conception of History (1894) |

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov[a] (Russian: Георгий Валентинович Плеханов, IPA: [ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf] ⓘ; 11 December [O.S. 29 November] 1856 – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revolutionary, philosopher and Marxist theorist. Known as the "father of Russian Marxism",[2] Plekhanov was a highly influential figure among Russian radicals, including Vladimir Lenin.

Born to a Tatar noble family, Plekhanov joined the Narodnik movement as a student. He was twice arrested and fled to Switzerland in 1880, where he continued his political activity and became a Marxist. In 1883, he helped found the first Russian Marxist group, Emancipation of Labour, and from 1900 co-edited the journal Iskra with Lenin. Though he supported Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1903, Plekhanov soon rejected his idea of democratic centralism, and became one of Lenin and Leon Trotsky's principal antagonists in the 1905 Revolution and Saint Petersburg Soviet.

During World War I, Plekhanov rallied to the cause of the Entente powers against Germany. He returned to Russia following the February Revolution of 1917, and was an opponent of the Bolshevik state which came to power in the October Revolution, considering the revolution "unprincipled" and a "violation of all the laws of history". Plekhanov died the next year of tuberculosis in Finland. Despite his vigorous and outspoken opposition to Lenin's political party in 1917, Plekhanov was held in high esteem by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union following his death as a founding father of Russian Marxism and a philosophical thinker.

Early life and education

[edit]Family and youth

[edit]Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov was born on 29 November 1856 in the Russian village of Gudalovka in the Tambov Governorate.[3] He was born into a minor gentry family of Tatar extraction.[3] Plekhanov's father, Valentin, was a member of the lower stratum of the landed gentry. He possessed about 270 acres of land and some 50 serfs.[3] Valentin was a military man who had served in the Crimean War and in the suppression of the 1863 Polish uprising. In later life, he managed his estate and was described by his children and former serfs as severe and sometimes violent.[4] Despite his opposition to the emancipation reform of 1861, which freed the serfs and deprived him of half his estate, he attempted to adapt to the new conditions of capitalism.[3] Valentin sought to instill in his children the values of manliness, courage, self-reliance, and activity, and discouraged idleness.[4]

Plekhanov's mother, Maria Feodorovna, was distantly related to the famed literary critic Vissarion Belinsky.[5] She was Valentin's second wife; they married in 1855, and Georgi was the first of their five children.[5] Maria was a gentle and compassionate woman who undertook the early education of her children.[5] She encouraged Georgi's intellectual interests, teaching him to read at an early age. Plekhanov later recalled that it was she who instilled in him a sense of altruism and justice.[5] His relationship with his mother was warm, while his relationship with his father was more reserved.[6]

Education and radicalization

[edit]When he was ten years old, Plekhanov's family enrolled him in the Voronezh Military Academy.[5] At the academy, he was influenced by his teacher, N. F. Bunakov, a proponent of liberal pedagogical ideas who instilled in Plekhanov a love of literature and a sense of responsibility to the Russian people.[7] Bunakov introduced him to the writings of radical literary critics like Belinsky and Nikolay Chernyshevsky, giving the young Plekhanov his first acquaintance with the ideas of the intelligentsia.[7] Under the influence of the radical poet Nikolay Nekrasov, he developed a deep sympathy for the suffering of the Russian people.[8] During his time at the academy, Plekhanov also broke with his mother's Orthodox faith and became an atheist, challenging the priest who taught sacred law with probing questions.[8]

In 1873, after graduating from the academy, Plekhanov registered at the Konstantinovskoe Military School in Saint Petersburg.[9] While in the capital, his interest in military drills waned as he spent more time with Russian literature and literary criticism. He soon decided against a military career and, after only one semester, withdrew from the school to prepare for the entrance examinations to the Mining Institute.[9] Plekhanov's decision to pursue a career in mining engineering rather than social studies was likely influenced by the radical spirit of the 1860s and 1870s, which was characterized by utilitarianism, positivism, and a high regard for the natural sciences.[10]

Revolutionary career

[edit]Populism and Zemlia i Volia

[edit]

Plekhanov arrived in St. Petersburg in 1873, just as a revolutionary populist movement, later known as Narodism, was burgeoning. This movement, inspired by the ideas of Alexander Herzen and Chernyshevsky, saw the collectivistic peasant commune as the nucleus of a future socialist Russia.[11] The populists, or Narodniks, were divided between two main factions: one, following Mikhail Bakunin, believed that the peasants were natural revolutionaries who could be immediately called to rebellion; the other, following Pyotr Lavrov, argued for a period of propaganda to prepare the peasantry for revolution.[11]

In the winter of 1875–76, Plekhanov was introduced to the revolutionary movement by Pavel Axelrod, a returned revolutionary who was hiding from the police.[12] Although initially hesitant to commit fully, Plekhanov was gradually drawn into the cause. He began attending clandestine meetings of revolutionary students and workers, and by early 1876, his room was being used for meetings.[12] The academic year of 1875–76 was decisive for his transformation into a revolutionist. As he devoted more time to revolutionary activity, his studies declined, and he was expelled from the Mining Institute at the end of his second year.[13]

In the autumn of 1876, Plekhanov joined the newly founded populist organization Zemlia i Volia (Land and Liberty).[14] On 6 December 1876, he delivered a fiery speech at a demonstration in front of the Kazan Cathedral, denouncing the autocracy and defending the ideas of Chernyshevsky.[14] This act put him "outside the law" and forced him to flee abroad.[15] During his time in Berlin and Paris, he became acquainted with the German Social Democratic Party, but his Bakuninist convictions led him to view their "moderation and regularity" with disdain.[15] He returned to Russia in mid-1877 and devoted himself to the revolutionary cause with tireless energy.[16] He worked among peasants, students, and factory workers in Saratov and St. Petersburg, carried brass knuckles, and slept with a revolver under his pillow.[16] His activities included writing inflammatory leaflets, agitating among workers during strikes, and delivering a eulogy at the funeral of the poet Nekrasov.[17]

Schism and exile

[edit]Beginning in 1878, a new trend of political terrorism gained momentum within Zemlia i Volia, a response to government repression and the failures of rural agitation.[18] This led to a split in the organization between the proponents of terrorism and the Derevenshchiki (villagers), who advocated for continued mass agitation in the countryside.[19] Plekhanov became the leading spokesman for the Derevenshchiki. While not opposed to violence in principle, he argued that a focus on political assassinations was a distraction from the more important work of building a mass movement among the people.[20] He feared that a program of terrorism would exhaust the party's resources and provoke even harsher government repression.[21]

The conflict came to a head at the Voronezh Congress in June 1879.[22] The terrorists, led by figures like Andrei Zhelyabov, argued for a campaign to assassinate Tsar Alexander II, while Plekhanov insisted that such a move would be a betrayal of the populist cause.[23] Finding himself isolated and his own faction willing to compromise, Plekhanov walked out of the congress in protest.[24] The split in Zemlia i Volia became final in October, with the terrorist faction forming the new organization Narodnaya Volya (The People's Will) and Plekhanov's faction establishing Chernyi Peredel (The General Redivision).[25]

Plekhanov's hopes for Chernyi Peredel were short-lived. The group failed to attract recruits or gain influence, as most radicals were drawn to the more dynamic and dramatic struggle of Narodnaya Volia.[26] His populist convictions were further shaken by his reading of sociological studies that suggested the Russian peasant commune was in a state of decay.[27] Facing political isolation and the threat of arrest, Plekhanov and his associates left Russia for Geneva in January 1880, beginning what would become a 37-year exile.[28]

Father of Russian Marxism

[edit]Conversion to Marxism

[edit]After emigrating to Western Europe, Plekhanov undertook an intensive study of the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. His populist faith had been shaken by the failures of the Narodnik movement, and he was now seeking a new theoretical foundation for the Russian revolutionary cause.[29] He was particularly struck by Engels's polemic against Pyotr Tkachev and his reading of the Communist Manifesto, which led him to reject the core tenets of populism.[30] Plekhanov became convinced that Russia, like the West, would have to pass through a stage of capitalism before it could achieve socialism.[31]

In his 1883 work Socialism and Political Struggle, Plekhanov laid out a new program for the Russian revolutionaries, based on the principles of Marxism. He argued that the struggle for socialism in Russia must be preceded by a "bourgeois" revolution that would overthrow the Tsarist autocracy and establish a democratic republic.[32] This revolution, he believed, would be carried out by a coalition of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The task of the socialists was to organize the nascent working class and instill in it a socialist consciousness, so that it could play an independent and leading role in the struggle.[33] In his 1885 book Our Differences, Plekhanov elaborated on these ideas, presenting a detailed Marxist analysis of Russian social and economic conditions and a critique of the populist program.[34]

Emancipation of Labour Group

[edit]

In 1883, in Geneva, Plekhanov, along with Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, and Leo Deutsch, founded the Emancipation of Labour, the first Russian Marxist political group.[35] The group's primary aim was to propagate Marxist ideas among Russian revolutionaries and to provide a theoretical foundation for a future Russian Social Democratic party.[36] They undertook the translation and publication of the works of Marx and Engels, as well as their own analyses of Russian social and economic life.[36]

For the first decade of its existence, the Emancipation of Labour Group faced significant challenges. They were met with hostility from the established populist and terrorist factions of the Russian revolutionary movement, who viewed their ideas as a betrayal of the cause.[37] They also received a cool reception from Western socialists, including Engels, who were more supportive of the more militant Narodnaya Volia.[36] The group was small and often isolated, struggling with financial hardship and the difficulties of smuggling their literature into Russia.[38] Plekhanov's own health suffered during this period; he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which would plague him for the rest of his life.[39]

Despite these difficulties, the group's efforts laid the groundwork for the rise of Marxism in Russia. Their critique of populism eroded the ideological foundations of the old revolutionary movement, while their propagation of Marxist ideas provided a new orientation for the younger generation of revolutionaries.[40] Their work was instrumental in the creation of a new political atmosphere in Russia, one in which Marxist ideas could become acceptable to Russian revolutionists.[40]

Leader of the RSDLP

[edit]Breakthrough and "Legal Marxism"

[edit]

In the early 1890s, the political climate in Russia began to change. The famine of 1891–92, which exposed the government's ineffectuality and callousness, shocked the intelligentsia into a new sense of social responsibility.[41] At the same time, Russia's rapid industrialization gave rise to a growing proletariat and a wave of labour strikes.[42] These developments seemed to confirm Plekhanov's predictions and created a fertile ground for the spread of Marxist ideas. A new generation of revolutionaries, including future leaders like Vladimir Lenin, Julius Martov, and Pyotr Struve, were drawn to Marxism and to the writings of Plekhanov, whom they regarded as the "master theoretician" of the movement.[43]

A key moment in the breakthrough of Russian Marxism was the publication in 1895 of Plekhanov's book, On the Development of the Monistic View of History.[44] Written as a polemic against the populists, the book presented a systematic exposition of the materialist conception of history. Published legally in Russia under the pseudonym N. Bel'tov, it was a resounding success, selling out in less than three weeks and profoundly influencing a generation of Russian Marxists.[44] The book's publication marked the beginning of the era of "Legal Marxism", a period in which the Tsarist government, misjudging the threat, allowed the publication of Marxist literature as a counter to the more feared populism.[45] Plekhanov and his followers seized this opportunity, publishing a stream of articles and books in the legal press that attacked populist ideology and advanced the Marxist cause.[46]

The successes of the 1890s also brought Plekhanov and the Emancipation of Labour Group into closer contact with activists in Russia. In May 1895, Lenin visited Geneva to meet with Plekhanov and Axelrod. The encounter marked the beginning of a collaboration between the old guard and the new generation of Marxists.[47] The St. Petersburg strikes of 1896, led by the newly formed League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, further demonstrated the growing influence of the Social Democrats. The strikes drew international attention, and Plekhanov and his group rallied support from Western socialists.[48] At the 1896 Congress of the Second International in London, a large Russian delegation was seated, representing Social Democratic groups from ten different cities. For the first time, the Russian Marxists could claim a place in the international socialist movement not by courtesy, but by right.[49]

Defender of the faith

[edit]The late 1890s saw the emergence of the first major ideological controversy within Russian Marxism, a trend known as "Economism".[50] The Economists, who arose from the practical work of agitation among the industrial workers, argued that the Social Democrats should focus on the economic struggle of the proletariat for better wages and working conditions, rather than on the political struggle for the overthrow of the autocracy.[51] This tendency found its expression in the St. Petersburg newspaper Rabochaia mysl' (Workers' Thought) and in the émigré journal Rabocheye Delo (The Workers' Cause).[52]

Plekhanov viewed Economism as a Russian variant of the Revisionist heresy of Eduard Bernstein, which had simultaneously emerged in the German Social Democratic Party.[50] He saw both as a dangerous deviation from orthodox Marxism, a surrender to the "spontaneity" of the working-class movement and a betrayal of the revolutionary goal of socialism.[53] For Plekhanov, the task of the Social Democrats was not to follow the workers, but to lead them, to raise their trade-union consciousness to the level of socialist consciousness, and to imbue them with an understanding of the necessity of political struggle.[54]

The conflict between Plekhanov's group and the Economists, who for a time gained a majority in the émigré Russian Social Democratic Union, was protracted and bitter.[52] After a series of clashes over the control of the Union's publications and resources, Plekhanov launched a fierce polemical assault on the Economists. In 1900, he published his Vademecum for the Editors of Rabochee Delo, a blistering critique that denounced the Economists for their theoretical errors and their abandonment of revolutionary principles.[55] The struggle against Economism and Revisionism solidified Plekhanov's image as the paramount defender of Marxist orthodoxy, but it also reinforced his "Jacobin" tendencies and his intolerance for ideological deviation.[56]

The 1903 split

[edit]Collaboration and conflict with Lenin

[edit]

The turn of the century marked a new phase in the history of Russian Social Democracy, one centered on the newspaper Iskra (The Spark). The enterprise was conceived by Lenin, Martov, and Alexander Potresov as a vehicle for combating Economism and uniting the dispersed Social Democratic organizations into a centralized party.[57] They sought the collaboration of the Emancipation of Labour Group, and in August 1900, Lenin traveled to Geneva to negotiate with Plekhanov. The initial encounter was stormy. Plekhanov, in a "Jacobin" mood after his battles with the Economists, was suspicious of Lenin's conciliatory draft for the newspaper's editorial policy, which he saw as an "opportunistic" concession to the very tendencies they were meant to fight.[56]

Despite the initial friction, an agreement was reached. The editorial board of Iskra would consist of six members: Plekhanov, Axelrod, and Zasulich from the old guard, and Lenin, Martov, and Potresov from the new generation.[56] Plekhanov's views, however, prevailed in the final editorial statement, which committed the paper to a hard, uncompromising line and the drawing of "lines of demarcation" between the orthodox and their opponents.[58] For a time, a more comradely relationship was established, as Lenin demonstrated his efficiency and reliability as an organizer.[58] The collaboration, however, was soon strained by new disagreements, this time over the party program, particularly the agrarian question.[59] Lenin's proposal for the nationalization of land in the "bourgeois" revolution was seen by Plekhanov and the other editors as a dangerous and ill-conceived departure from Marxist doctrine.[60]

Second Congress

[edit]The 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party convened in Brussels in July 1903, its main purpose being to unite the party and adopt a program and rules.[61] The Iskra faction, which Plekhanov and Lenin jointly led, held a solid majority of the delegates.[61] The congress began with the easy defeat of the Bundists and the Economists, but the unity of the Iskrists soon shattered. The split occurred over the definition of party membership, as formulated in Paragraph 1 of the party rules.[62] Lenin's draft proposed a narrow, centralized party of professional revolutionaries, while Martov's draft advocated for a broader party, open to any who accepted the party program and worked under the control of one of its organizations.[62]

To the surprise of many, Plekhanov sided with Lenin against his old comrade Martov. He argued that Martov's formula would open the party to "all elements of dispersion, wavering, and opportunism," particularly the "bourgeois individualism" of the intelligentsia.[63] In a famous speech that would haunt him for years, he declared that "the success of the revolution is the highest law" and that, if the success of the revolution demanded it, the party might even have to limit democratic principles like universal suffrage.[64] Despite Plekhanov's support, Lenin's draft was defeated by a majority that included the Bundists and Economists.[65] However, after the Bund and the Economists walked out of the congress, Lenin's faction, now known as the Bolsheviks (from bolshinstvo, meaning "majority"), was left with a slim majority. The opposition became known as the Mensheviks (from menshinstvo, meaning "minority").[66] Lenin pressed his advantage, securing the election of a Central Committee and an Iskra editorial board composed of his supporters. At the conclusion of the congress, Plekhanov stood firmly in the Bolshevik camp.[66]

Break with Lenin

[edit]

Plekhanov's alliance with Lenin was short-lived. Caught in the crossfire of the post-congress factional struggle, he soon began to waver. The Mensheviks, led by Martov, boycotted Iskra and the Central Committee, and sought to undermine Lenin's control of the party.[67] Plekhanov, horrified by the prospect of a new split, recoiled from Lenin's intransigence. He now saw the "state of siege" in the party, which Lenin considered indispensable, as a "heinous political crime".[68] In October 1903, he broke with Lenin and used his position on the Iskra board to recall the old Menshevik editors.[68]

In the months that followed, Plekhanov became one of the leading critics of Lenin and Bolshevism. He now saw Lenin's organizational scheme, as outlined in What Is to Be Done?, as a perversion of Marxism.[69] He charged Lenin with creating a "monolithic organizational conception" that confused the dictatorship of the proletariat with a "dictatorship over the proletariat".[70] He accused the Bolsheviks of "Bonapartism" and of attempting to realize the "ideal of the Persian Shah".[70] Plekhanov's critique of Lenin's conception of the party was trenchant and prophetic, but it also revealed the fundamental contradictions in his own position. He had embraced the elitist and centralist logic of the Iskra period, only to recoil from its ultimate consequences when they were drawn by Lenin.[71]

1905 Revolution

[edit]

The 1905 Russian Revolution put Plekhanov's revolutionary theory to the test. He viewed the upheaval as a "bourgeois" revolution, a confirmation of the historical prospectus he had elaborated two decades earlier.[72] His main tactical preoccupation was to ensure a coalition between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie against the autocracy. "March separately, strike together," was his resounding slogan.[73] However, the course of the revolution soon revealed the deep contradictions in his strategy. The bourgeoisie, frightened by the militancy of the proletariat, proved a timid and unreliable ally.[74] The proletariat, on the other hand, was not content to play the role of junior partner to the bourgeoisie. The December Uprising, led by the Social Democrats, was a case in point. Plekhanov, horrified by what he saw as a premature and isolated action, famously declared: "They should not have taken to arms."[75]

Plekhanov's conduct during the revolution alienated him from both the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions. The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, rejected his insistence on an alliance with the bourgeoisie and called for a "democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry."[76] The Mensheviks, while sharing his general strategic outlook, recoiled from what they saw as his "opportunistic" and "Cadet-like" tactics.[76] Plekhanov found himself politically isolated, a "historic monument" rather than an active leader of the revolutionary movement.[77] The failure of the revolution was a profound personal and political blow. His revolutionary system, built on the assumption of an organic link between the bourgeois and socialist revolutions, had been shattered by the realities of the Russian situation.[78]

War and revolution

[edit]World War I

[edit]With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Plekhanov adopted a staunchly "Defensist" position, supporting the Allied cause against the Central Powers.[79] He saw the war as a struggle between the democratic nations of the West and the imperialistic, reactionary regime of Germany.[80] A German victory, he argued, would be a disaster for the cause of socialism, while an Allied victory would advance the prospects of democracy and progress in Russia and throughout Europe.[81] His position was a dramatic reversal of the internationalist and defeatist stance he had taken during the Russo-Japanese War.[82] It was a break with the majority of the international socialist movement, including his old comrades Axelrod and Martov, who took a centrist, anti-war position.[83]

Plekhanov's Defensism was a logical, if extreme, development of the nationalistic and state-centric tendencies that had been latent in the Marxism of the Second International.[84] It was also a manifestation of his growing alienation from the revolutionary movement. He had come to value the political and cultural attainments of the "bourgeois" West, and he now saw them as worth defending against the "Asiatic barbarism" of German imperialism.[80] His wartime writings are filled with a new appreciation for the moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant, a thinker he had once castigated as the epitome of bourgeois hypocrisy.[85] In embracing the Kantian ethics of national self-determination, Plekhanov was, in effect, displacing the fundamental tenets of his own Marxist system.[85]

Return to Russia and 1917 Revolution

[edit]

Plekhanov returned to Russia in March 1917, after 37 years of exile. He was hailed as a hero of the revolution, a "father of Russian Marxism" who had returned to see his prophecies fulfilled.[86] However, he soon found himself isolated and out of step with the new revolutionary reality. He gave his full support to the Provisional Government and to the continuation of the war, a position that put him at odds with the Petrograd Soviet and the majority of the socialist parties.[87] He was a fierce opponent of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, whose call for "all power to the soviets" and an immediate end to the war he denounced as "ravings" and a betrayal of the revolution.[88]

In 1917, Plekhanov did everything he could to stem the tide of class struggle and to promote a coalition of all "live forces" of the nation against the external enemy.[88] His position was virtually indistinguishable from that of the liberal Cadet Party. He was offered a ministerial post in the Provisional Government, but his name was vetoed by the Soviet Executive Committee.[89] He was praised by the liberal and conservative press, but he was increasingly ignored by the revolutionary masses.[89] The October Revolution was a final, crushing blow. He saw it as a premature and disastrous seizure of power, a "bloody epilogue to the reforms of 1861" that would lead not to socialism but to a new form of "patriarchal and authoritarian communism".[90]

Final months and death

[edit]After the October Revolution, Plekhanov's health, already precarious, rapidly deteriorated. He was hounded by the new regime, and his apartment was raided by a detail of soldiers and sailors.[91] Fearing for his life, his wife moved him to a sanitarium in Terijoki, Finland, where he spent his last months.[91] He died of tuberculosis on 30 May 1918. Despite the disapproval of the Bolshevik authorities, his funeral in Petrograd was attended by a large crowd of workers and intellectuals.[92] He was buried in the Volkovo Cemetery next to his intellectual forebear, Vissarion Belinsky.[92]

Legacy

[edit]

Plekhanov's legacy is complex and contested. He is widely recognized as the "Father of Russian Marxism", the man who laid the theoretical foundations for the Social Democratic movement in Russia. His writings, particularly Socialism and Political Struggle and On the Development of the Monistic View of History, were instrumental in the conversion of a generation of revolutionaries, including Lenin, to Marxism.[44] His two-stage theory of revolution, which posited a "bourgeois" revolution as a necessary prelude to a socialist revolution, became the official doctrine of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party and a cornerstone of Menshevik ideology.[33]

After 1917, Plekhanov was rehabilitated by the Bolsheviks and enshrined in the Soviet pantheon as a founding father of Marxism in Russia. Lenin, despite their political differences, paid tribute to Plekhanov's theoretical contributions, particularly his philosophical works.[93] However, his political legacy was more problematic. His opposition to Bolshevism in 1917 and his Defensist stance during World War I were either ignored or condemned. His Menshevik affiliation was a source of embarrassment, and his critique of Lenin's organizational principles was suppressed.[94]

Plekhanov's historical reputation has been shaped by the political struggles of the 20th century. In the West, he has often been seen as a more "orthodox" and "democratic" Marxist than Lenin, a forerunner of the Menshevik alternative to Bolshevism.[95] In the Soviet Union, he was presented as a great theoretician who, despite his "Menshevik errors", had helped to pave the way for the victory of Lenin and the Bolsheviks.[96] His own tragic political trajectory, which saw him move from the center of the revolutionary movement to its margins, reflects the profound contradictions of his own thought and of the historical project to which he dedicated his life.[97]

Personal life

[edit]In October 1876, Plekhanov married Natalia Smirnova, a radical medical student.[15] They shared an apartment with a third student, and after his flight from Russia, she accompanied him abroad.[15] Little is known about their life together; they separated after two years and were officially divorced in 1908.[98]

In 1879, Plekhanov entered into a relationship with Rosaliia Bograd, a 23-year-old medical student from a well-to-do Jewish family in Kherson.[99] She joined him in exile in Geneva in 1880 and became his lifelong companion.[100] Rosaliia was a dedicated socialist who shared in his political struggles and supported him through his long illness.[101] She completed her medical studies in Geneva and, through her practice, provided the main source of income for the family.[102] They had four children: their first daughter, Vera, died in infancy in 1880; a second child was born in 1881 and a third in 1883.[103] One of these children also died at the age of four.[100] Their two surviving daughters were named Lydia and Eugenia.[104] After his divorce from Natalia, Plekhanov legally married Rosaliia in 1908.[100]

During his exile, Plekhanov and his family lived a non-bohemian, orderly life that surprised some of his younger, more radical compatriots.[104] They maintained a comfortable apartment in Geneva for over twenty years and also had winter quarters on the Italian Riviera.[104] His daughters were educated in European schools and knew little of the radical milieu of their parents' youth.[104]

Philosophical and historical thought

[edit]

Plekhanov was one of the few followers of Marx and Engels who took philosophy as seriously as he did politics.[93] He saw Marxism as a complete and materialistic worldview, and he considered its philosophical foundations to be indispensable for the socialist movement.[93] He devoted much of his intellectual energy to the study of the history of philosophy and to the defense of what he termed "dialectical materialism" against its critics.[96]

Philosophy

[edit]Plekhanov's philosophical work was rooted in the materialist tradition of the 18th-century French philosophers, such as Baron d'Holbach and Claude Adrien Helvétius. He praised them for their defense of materialism but criticized their "metaphysical" inability to account for historical development.[105] He found the necessary corrective in the dialectical method of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose philosophy, he argued, had provided a "complete and revolutionary" conception of history.[106] However, Hegel's system was marred by its idealism. It was left to Marx and Engels to synthesize the materialism of thinkers like Ludwig Feuerbach with the dialectics of Hegel, thus creating the "scientific" philosophy of dialectical materialism.[107]

A central theme in Plekhanov's philosophy is the tension between determinism and free will. He insisted on the objective, law-abiding nature of the historical process, which he saw as independent of human will.[107] However, he also recognized the role of individual action and "passion" as an "indispensable link" in the chain of historical necessity.[108] His own passionate political engagement seemed to belie a purely deterministic outlook, a contradiction he never fully resolved.[109] He also grappled with the relationship between evolution and revolution, arguing that they were organically linked but rejecting the idea that revolution was an inevitable outcome of evolution.[109]

History

[edit]Plekhanov's major historical work was his unfinished History of Russian Social Thought.[110] In it, he applied the principles of historical materialism to the study of Russian history, seeking to uncover the "sociological equivalent" of the ideas and institutions of the past.[110] He drew heavily on the work of "bourgeois" historians like Sergey Solov'ev and Vasily Kliuchevsky, while also subjecting their interpretations to a Marxist critique.[111]

Plekhanov's central thesis was that Russia's historical development was fundamentally different from that of the West. He characterized pre-Petrine Russia as an "Oriental despotism", a society based on a stagnant, natural economy in which the state controlled the means of production and all classes of the population were reduced to utter dependence.[112] The reforms of Peter the Great initiated a process of "Europeanization", which introduced capitalism and created the social forces—the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, and the intelligentsia—that would ultimately challenge and overthrow the old despotic order.[113] This historical construction provided the theoretical underpinning for his two-stage theory of revolution.

Art and aesthetics

[edit]Plekhanov is considered a founder of Marxian literary criticism. He believed that art, like all forms of social thought, was a reflection of the economic and social conditions of its time.[114] He proposed a two-step method for the critic: first, to translate the idea of a given work from the language of art to the language of sociology, in order to find its "sociological equivalent"; and second, to evaluate its aesthetic merits.[114] His aesthetic criteria were based on truthfulness, unity of form and content, and the loftiness of the mood it expressed.[115]

Plekhanov's critical method was a synthesis of the ideas of Belinsky and Hippolyte Taine with the sociological principles of Marxism.[116] He applied it to the study of French 18th-century art, tracing the succession of schools from the classicism of Le Brun to the decadence of François Boucher and the revolutionary art of Jacques-Louis David.[117] He was a harsh critic of "art for art's sake" and Impressionism, which he saw as signs of bourgeois decadence.[118] While he insisted on the autonomy of the aesthetic judgment, his own criticism often revealed a political preference for art that reflected the "great 'truth' of his time," which for him was Marxism.[119]

Works

[edit]- Socialism and the Political Struggle (1883) Plekhanov: Socialism and Political Struggle (1883)

- Our differences (1885) G.V. Plekhanov: Our Differences (1885)

- G. I. Uspensky (1888)

- A New Champion of Autocracy (1889)

- S. Karonin (1890)

- The Bourgeois Revolution (1890–1891)

- The Materialist Conception of History (1891)

- For The Sixtieth Anniversary of Hegel's Death (1891)

- Anarchism & Socialism (1895)

- The Development of the Monist View of History (1895)

- Essays on the History of Materialism (1896)

- N. I. Naumov (1897)

- A. L. Volynsky: Russian Critics. Literary Essays (1897)

- N. G. Chernyshevsky's Aesthetic Theory (1897)

- Belinski and Rational Reality (1897)

- On the Question of the Individual's Role in History (1898)

- N. A. Nekrasov (1903) In Russian.

- Scientific Socialism and Religion (1904)

- On Two Fronts: Collection of Political Articles (1905) In Russian.

- French Drama and French Painting of the Eighteenth Century from the Sociological Viewpoint (1905)

- The Proletarian Movement and Bourgeois Art (1905)

- Henrik Ibsen (1906)

- Us and Them (1907) In Russian.

- On the Psychology of the Workers' Movement (1907)

- Fundamental Problems of Marxism (1908)

- The Ideology of Our Present-Day Philistine (1908)

- Tolstoy and Nature (1908)

- On the So-Called Religious Seekings in Russia (1909)

- N. G. Chernyshevsky (1909)

- Karl Marx and Lev Tolstoy (1911)

- A. I. Herzen and Serfdom (1911)

- Dobrolyubov and Ostrovsky (1911)

- Art and Social Life (1912–1913)

- Year of the Motherland: Complete Collected Articles and Speeches, 1917–1918, In Two Volumes. Volume 1; Volume 2 (1921) In Russian.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pronunciation: /plɪˈkɑːnɒf/, US also /plɪˈkɑːnɔːf/[1]

References

[edit]- ^ "Plekhanov". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Baron, Samuel H. (1954). "Plekhanov and the Origins of Russian Marxism". The Russian Review. 13 (1): 38–51. doi:10.2307/125906. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 125906.

- ^ a b c d Baron 1963, p. 4.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Baron 1963, p. 6.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 6, 5.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 7.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 8.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 9.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 13.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 16.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 17.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Baron 1963, p. 19.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 20.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 32.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 33.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 34.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 37.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 39.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 41.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 44.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 45.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 55.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 47, 59.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 60.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 66, 68.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 74.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 90.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 89.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 91.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Baron 1963, p. 103.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 102.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 104, 110.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 111.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 115.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 120.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 122.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Baron 1963, p. 125.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 124.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 127.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 154.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 134.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 135.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 147.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 171.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 165.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 174.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 175.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Baron 1963, p. 186.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 181.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 187.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 197.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 200.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 204.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 209.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 210.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 214.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 212.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 213.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 217.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 218.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 221.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 220.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 216.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 233.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 235.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 237.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 239.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 241.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 249.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 247.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 297.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 298.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 299.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 290.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 305.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 301.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 302.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 315.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 317.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 319.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 322.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 330.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 325.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 326.

- ^ a b c Baron 1963, p. 258.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 248.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 332.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 259.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 333.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 19, 56.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Baron 1963, p. 56.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 226.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Baron 1963, p. 229.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 261.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 262.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 263.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 264.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 265.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 267.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 268.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 274–276.

- ^ a b Baron 1963, p. 279.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 281.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 282.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Baron 1963, p. 285.

- ^ Baron 1963, pp. 287–288.

Works cited

[edit]- Baron, Samuel H. (1963). Plekhanov: The Father of Russian Marxism. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. LCCN 63-10732 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

[edit]- Baron, Samuel H. Plekhanov in Russian History and Soviet Historiography. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

- Georgi Plekhanov: Selected Philosophical Works in Five Volumes. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974.

External links

[edit]- Progress Publishers put out a five-volume Selected Philosophical Works of Georgi Plekhanov in English between 1974 and 1981:

- Works by Georgii Valentinovich Plekhanov at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Georgi Plekhanov at the Internet Archive

- Georgi Plekhanov Internet Archive, Marxists Internet Archive, marxists.org/

- Georgi Plekhanov Biography, Spartacus UK, spartacus-educational.com/

- Georgii Plexhanov Collected Works in 24 Volumes Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Plekhanov Fond, plekhanovfound.ru/ In Russian.

- Tomb of Plekhanov

- The Plekhanov House in The National Library of Russia Archived 1 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Archive of Georgij Valentinovič Plechanov Papers at the International Institute of Social History

- Newspaper clippings about Georgi Plekhanov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1856 births

- 1918 deaths

- People from Gryazinsky District

- People from Lipetsky Uyezd

- People from the Russian Empire of Tatar descent

- Narodniks

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Mensheviks

- Marxist theorists

- Philosophers from the Russian Empire

- Political writers from the Russian Empire

- Marxists from the Russian Empire

- Revolutionaries from the Russian Empire

- 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Tuberculosis deaths in Finland

- Burials at Volkovo Cemetery