Draft:Esther's Narration in Bleak House

| Submission declined on 10 May 2025 by Asilvering (talk). This submission reads more like an essay than an encyclopedia article. Submissions should summarise information in secondary, reliable sources and not contain opinions or original research. Please write about the topic from a neutral point of view in an encyclopedic manner.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

| Submission declined on 28 April 2025 by Protobowladdict (talk). This submission reads more like an essay than an encyclopedia article. Submissions should summarise information in secondary, reliable sources and not contain opinions or original research. Please write about the topic from a neutral point of view in an encyclopedic manner. Declined by Protobowladdict 2 months ago. |  |

Comment: Sorry to decline this after all the work you went to to translate it, but this is pure WP:OR and probably shouldn't be on fr-wiki either. asilvering (talk) 05:06, 10 May 2025 (UTC)

Comment: Sorry to decline this after all the work you went to to translate it, but this is pure WP:OR and probably shouldn't be on fr-wiki either. asilvering (talk) 05:06, 10 May 2025 (UTC)

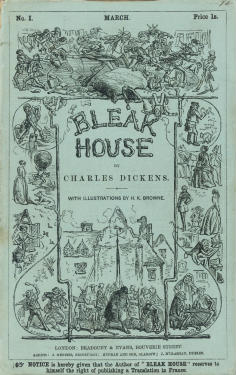

Cover of the first issue, March 1852 | |

| Author | Charles Dickens |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel (institutional and social satire) |

| Publisher | Chapman & Hall |

| Publication place | |

Bleak House, a novel by Charles Dickens, was first published as a serial between March 1852 and September 1853 by Chapman & Hall. It employs a dual narrative structure, alternating between a third-person omniscient perspective and a first-person narrative by Esther Summerson, introduced in the third chapter, titled "A Progress".[1] This narrative technique distinguishes the novel and supports its exploration of themes such as identity, absence, and social institutions.

The rupture

[edit]In the third chapter of Bleak House, titled "A Progress", the novel introduces a first-person narrative through Esther Summerson, beginning with the sentence: “I have a great deal of difficulty in beginning to write my portion of these pages, for I know I am not clever.”[2] This marks a shift from the third-person narrative of the preceding chapters.[1]

Narrative rupture

[edit]The opening sentence of Esther’s narrative indicates its retrospective nature, as it is delivered by a narrator who has not yet identified themselves.[3] The narrative shifts from an impersonal third-person perspective to a first-person one, employing the personal pronoun "I" three times, the possessive adjective "my", and the demonstrative "these" in the phrase "these pages", which emphasizes the narrator’s ownership of the text.[4] This shift in enunciation distinguishes the narrative from the earlier chapters.[5][1][N 1]

This first-person narrative is not embedded within the third-person narrative, as defined by Roland Barthes in his analysis of Balzac’s Sarrasine, where a narrative may be contained within a frame narrative.[6] Instead, it alternates with the third-person narrative throughout the novel, creating a counterpoint in enunciation.[5]

Establishment of a new temporality

[edit]The first-person narrative introduces a new temporality, characterized by the past tense, as seen in the second sentence: “I always knew that.”[2] This contrasts with the present tense used in the third-person narrative of the first two chapters, which eliminates temporal perspective.[1] The past tense establishes the narrative as an autobiography, recounting Esther’s life from a retrospective viewpoint.[3] The first three sentences of the chapter illustrate this temporal shift: the first uses the present tense, the second the past tense (preterite), and the third combines both.[7] This allows a distinction between the narrating subject (Esther as narrator) and the narrated subject (Esther as heroine).[4]

Introduction of a dialectic of the self

[edit]Esther’s narrative establishes a dialectic through which her narrative voice asserts itself.[5]

A Self that distances itself from the narrative

[edit]Esther’s narrative begins with a statement of distance: “I have a great deal of difficulty in beginning to write,” yet it also expresses inclusion: “I always knew that.”[8] The narrative situation is staged through the relationship between Esther as a child and her doll, where the child, identified as female, assumes the role of narrator, and the doll serves as the narratee.[8] Both the narrator and the heroine use the phrase “I am not clever,” with the narrator addressing the reader in the present narration and the heroine speaking to the doll in the past, as seen in: “Now, Dolly, I am not clever, you know very well, and you must be patient with me, like a dear!”[2][4][8] This shift to direct speech actualizes the past.[8]

Hypotyposis and the will to self-depreciate

[edit]The narrative employs hypotyposis, a rhetorical figure involving vivid description or narrative, as defined by Henri Suhamy: “Hypotyposis is a description or narrative that not only seeks to signify its object through language, but also strives to touch the imagination of the receiver and to evoke the described scene by imitative or associative strategies.”[9] This is evident in the depiction of Esther and her doll, presented as a two-character interaction.[8] Esther’s self-description as “not clever” reflects a negative self-definition, yet her act of narration asserts her presence as a narrator.[4][8]

Establishment of an ironic vision

[edit]The narrative creates irony through the gap between narrative and discourse, particularly in the contrast between Esther’s self-description as “not clever” and her act of writing or speaking.[10] This irony is reinforced by hypotyposis, which links the past (“told”) and present (“to write”) through the recurring deficiency of “not clever.”[10] Esther’s narration is presented as a means of self-creation through speech.[4]

A limited lucidity

[edit]Esther’s narrative reflects a limited perspective, as she writes to recount her experiences but consistently describes herself negatively, a trait evident in both her childhood and adult narration.[7][10] This is achieved through restricted focalization, where Esther limits her presentation to self-deprecation, using negative constructions such as “never,” “not,” and “none,” alongside modal verbs like “could,” and phrases like “so different,” “so poor,” “so trifling,” “so far off,” “I never could,” “could never,” “very sorry,” and “if I had been a better girl.”[7]

A self unknowing itself in the superlative

[edit]Esther’s self-description employs emphatic negative language, constructing her identity in terms of absence, which parallels the fog described in the first chapter.[11] This metaphorical relationship links the physical fog to Esther’s lack of clarity about her identity.[12]

“The objective correlative” (T. S. Eliot)

[edit]The fog in the novel’s opening serves as an “objective correlative,” a term popularized by T. S. Eliot in 1921, defined as: “The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an ‘objective correlative’; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.”[11][N 2][13] This is reflected in the repeated use of “never” in Esther’s narrative: “I had never heard my mama spoken of. I had never heard of my papa either, but I felt more interested about my mama. I had never worn a black frock, that I could recollect. I had never been shown my mama's grave. I had never been told where it was. Yet I had never been taught to pray for any relation but my godmother.”[2] This anaphora echoes the repetition of “fog” in the first chapter, emphasizing absence and obscurity.[11] The anaphora underscores Esther’s lack of knowledge about her mother, a central theme of her narrative.[14]

Absence

[edit]Esther’s narrative centers on the absence of her mother, whom she believes to be dead but later discovers through the revelation of secrets surrounding her birth.[14] This absence is conveyed through a lack of signs, such as mourning clothes, a grave, prayers, or discussions about her mother.[15]

Textual signs of absence

[edit]Erasure of the birth

[edit]The sixth paragraph describes an episode where Esther’s birthday is denied: “It was my birthday […] I happened to look timidly up from my stitching, across the table at my godmother, and I saw in her face, looking gloomily at me, ‘It would have been far better, little Esther, that you had had no birthday, that you had never been born!’ […] I put up my trembling little hand to clasp hers or to beg her pardon with what earnestness I might, but withdrew it as she looked at me, and laid it on my fluttering heart. She raised me, sat in her chair, and standing me before her, said slowly in a cold, low voice—I see her knitted brow and pointed finger: ‘Your mother, Esther, is your disgrace, and you were hers. The time will come—and soon enough—when you will understand this better and will feel it too, as no one save a woman can. I have forgiven her’—but her face did not relent—‘the wrong she did to me, and I say no more of it, though it was greater than you will ever know—than anyone will ever know but I, the sufferer. For yourself, unfortunate girl, orphaned and degraded from the first of these evil anniversaries, pray daily that the sins of others be not visited upon your head, according to what is written. Forget your mother and leave all other people to forget her, who will do her unhappy child that greatest kindness’.”[2] This reinforces the theme of absence by negating Esther’s identity.[16]

The mother’s double negatives

[edit]The absence of Esther’s mother is contrasted with the presence of two substitute figures, her godmother and Mrs. Rachel, described as negative doubles.[16] The godmother is strict and denies Esther’s birthday, while Mrs. Rachel responds to Esther’s questions with “Good night!,” withholding information, as in the phrase “she took away the light.”[2][15] This act symbolizes ignorance, another objective correlative.[16] The godmother is introduced in the third paragraph: “I was brought up, from my earliest remembrance – like some of the princesses in the fairy stories […] by my godmother.”[2] The fairy-tale allusion contrasts with her harsh demeanor, resembling a wicked fairy.[16]

A symbolic staging

[edit]The final paragraph stages a domestic scene with iterative elements, described as: “the clock ticked,” “the fire clicked,” evoking nursery rhymes.[15] Despite traditional elements of comfort—fire, clock, table, meal—the scene lacks emotional connection, with dinner described as “over” and the table separating Esther and her godmother: “across the table.”[2][15] This metonymy highlights their emotional distance.[16] The scene is singulative, occurring once, unlike the iterative narrative elsewhere.[N 3][N 4][17]

The overdetermined image of the doll

[edit]Esther’s doll is described as an overdetermined image, embodying filial and maternal roles.[N 5][18] It represents an attempt to compensate for the absent mother.[15] This connects to the second chapter’s phrases “faint to death” and “bored to death,” linking Esther’s emotional void to Lady Dedlock’s ennui.[19][20]

Narrative structure of absence

[edit]Esther’s narrative employs restricted focalization, limiting her perspective, supplemented by an external focalization that distances the narrative from the events.[20]

Superimposition of two discourses

[edit]The narrative contains two voices: Esther’s and an unidentified voice, evident in the description of the godmother:

Like some of the princesses in the fairy stories, only I was not charming — by my godmother. At least, I only knew her as such. She was a good, good woman! She went to church three times every Sunday, and to morning prayers on Wednesdays and Fridays, and to lectures whenever there were lectures; and never missed. She was handsome; and if she had ever smiled, would have been (I used to think) like an angel — but she never smiled. She was always grave and strict. She was so very good herself, I thought, that the badness of other people made her frown all her life. I felt so different from her, even making every allowance for the differences between a child and a woman; I felt so poor, so trifling, and so far off that I never could be unrestrained with her — no, could never even love her as I wished. It made me very sorry to consider how good she was and how unworthy of her I was, and I used ardently to hope that I might have a better heart; and I talked it over very often with the dear old doll, but I never loved my godmother as I ought to have loved her and as I felt I must have loved her if I had been a better girl.

The godmother’s religious activities—three Sunday services, two matins prayers, and frequent sermons—are detailed, presenting her as a stock character.[20] Contradictions in Esther’s narrative, such as “I used ardently that I might have a better heart” versus “my disposition is very affectionate,” or “I had always rather a noticing way” versus “I have not by any means a quick understanding,” highlight a gap between her childhood and adult perspectives.[3][21] The comparison of the godmother to an angel is qualified by “I used to think” and negated by “but she never smiled.”[3]

An ironic counter-discourse

[edit]Esther’s adult narrative shows limited detachment, as seen in “At least I only knew her as such,” suggesting some awareness, yet her self-deprecation persists.[21][22] The narrative employs irony without reaching parody, balancing the Victorian melodrama of a suffering heroine with nuanced pathos.[3][21] Esther’s discourse alternates between self-assertion through frequent use of the first-person pronoun and self-denial.[22]

The reader: ultimate figure of absence

[edit]The hypotyposis in the first paragraph positions the reader as a figure of absence for Esther, who engages with others’ perspectives, such as the godmother’s gaze or the doll’s vacant eyes, described as “staring […] at nothing” or “whose eyes were fixed on me—or rather, I think, on nothing.”[23] Esther’s discourse, marked by restricted focalization, both reveals her frustrations and maintains an ironic distance.[21][23]

Theme of absence

[edit]The third chapter’s focus on absence shapes the novel’s narrative structure, emphasizing Esther’s lack of maternal connection and identity.

Rejection of the two foundational assets

[edit]Esther’s narrative denies her two key heroic attributes: birth and personal merit.[21] She seeks her birth to define her identity, claiming “I had always a rather noticing way,” but undermines this with “But even that may be my vanity.”[2][3] This creates suspense around her mother’s absence while highlighting her perceived inferiority.[23]

Affirmation of alienation

[edit]Esther’s identity is defined externally, as she notes: “They called me.”[21] Her name, “Esther,” is one of many labels, including later nicknames, reflecting her estrangement from herself.[21][23]

The subversion of discourse

[edit]The shift from a near-omniscient third-person narrator to a first-person narrator who denies her uniqueness introduces a complex narrative dynamic.[3] Esther, a female narrator, writes “this portion of these pages,” yet her femininity is primarily thematic, tied to the absence of her mother rather than her narrative voice.[24] An underlying narrative authority shapes her discourse, contributing to the novel’s exploration of alienation.[25][24]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In a work, several diegetic levels can often be distinguished: the extradiegetic level is the level of the narrator when they are not part of the fiction (for example, an omniscient narrator), knowing everything that exists outside of the fiction; the diegetic or intradiegetic level is the level of the characters, their thoughts, and actions; the metadiegetic or hypodiegetic level occurs when the diegesis contains another diegesis, for example, a character-narrator; a typical case is Scheherazade in One Thousand and One Nights, or the numerous digressions by Jacques in Jacques the Fatalist and His Master by Denis Diderot. At the metadiegetic level, when the character-narrator takes part in the elements of the story they are recounting, they are said to be homodiegetic; when they narrate stories in which they are absent, they are said to be heterodiegetic.

- ^ The term objective correlative was popularized in critical vocabulary by T. S. Eliot in 1921 in an essay on Hamlet. The popularity of the term always surprised its author, who had used it without attaching much importance to it.

- ^ Iterative: that which is repeated, done several times.

- ^ Singulative: that which happens only once.

- ^ Overdetermination: action by which an element is determined by multiple factors [Psychology].

References

[edit]For additional resources, see the Bleak House Page,[26] the Bleak House Bibliography for 2012, the Dickens Universe and adjunct conference on Dickens, Author and Authorship in 2012,[27] and Supplemental Reading About Bleak House.[28]

- ^ a b c d Ferrieux 1983

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dickens 1977

- ^ a b c d e f g Salotto 1997, pp. 333–349

- ^ a b c d e Moseley 1985, p. 39

- ^ a b c Manar 1983, p. 35-46

- ^ Barthes 1970, p. 21

- ^ a b c Barker 2009, p. 9

- ^ a b c d e f Ferrieux 1983

- ^ Suhamy 2004, p. 83

- ^ a b c Ferrieux 1983

- ^ a b c Ferrieux 1983

- ^ Moseley 1985, p. 36

- ^ "What is the Objective Correlative?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Moseley 1985, p. 41

- ^ a b c d e Ferrieux 1983

- ^ a b c d e Matsuura 2005, pp. 60–79

- ^ "LE TEMPS NARRATIF" [NARRATIVE TIME] (in French).

- ^ "Surdétermination" [Overdetermination]. linternaute.fr (in French). January 2025.

- ^ Storey 1987, p. 21

- ^ a b c Ferrieux 1983

- ^ a b c d e f g Ferrieux 1983

- ^ a b Harvey 1962, p. 149

- ^ a b c d Galloway, Shirley. "Bleak House: Public and Private Worlds".

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1983

- ^ Kaempfer, Jean; Zanghi, Filippo (2003). "Voix narrative" [Narrative voice] (in French).

- ^ "Bleak House: Selected Bibliography". Archived from the original on January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Bleak House Bibliography for 2012 Dickens Universe and adjunct conference on "Dickens! Author and Authorship in 2012"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2014.

- ^ "Bleak House discussion". Goodreads. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]Book

[edit]- Dickens, Charles (1977). Bleak House. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-09332-2.

General works

[edit]- Schlicke, Paul (2000). Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866253-2.

- Davis, Paul (1999). Charles Dickens from A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-4087-7.

- Jordan, John O (2001). The Cambridge companion to Charles Dickens. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Paroissien, David (2011). A Companion to Charles Dickens. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-65794-2.

- Davis, Paul (2007). Critical Companion to Charles Dickens, A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-6407-6.

- Suhamy, Henri (2004). Les Figures de style [Figures of speech]. Que sais-je? (in French). Paris: PUF. ISBN 2-13-054551-3.

Specific works

[edit]General

[edit]- Harvey, W. J. (1962). "Chance end Design in 'Bleak House". Dickens and the Twentieth Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Barthes, Roland (1970). S/Z (in French). Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 2-02-004349-1.

- Newsom, Robert (1977). Dickens on the Romantic Side of Familiar Things: Bleak House and the Novel Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 114–162.

- Ferrieux, Robert (1983). Bleak House (in French and English). Perpignan: Université de Perpignan Via Domitia.

- Bloom, Harold (1987). Dickens's Bleak House. New York: Chelsea House Pub. ISBN 0-87754-735-1.

- Storey, Graham (1987). Charles Dickens's Bleak House. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Manar, Hammad (1983). "L'énonciation : procès et système »" [Enunciation: Process and System]. Langages, 18e année, no 70 [Languages, 18th year, no. 70] (in French). pp. 35–46.

Esther Summerson

[edit]- Broderick, James H; Grant, John E (1958). "The Identity of Esther Summerson". Modern Philology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 252 sq.

- Axton, William (1965). "The Trouble With Esther". Modern Language Quarterly. pp. 545–557.

- Axton, William (1966). "Esther's Nicknames, A Study in Relevance". The Dickensian 62, 3. Canterbury: University of Kent. pp. 158–163.

- Zwerdling, Alex (1973). "Esther Summerson Rehabilitated". PMLA. 88. Los Angeles: 429–439.

- Wilt, Judith (1973). "Confusion and Consciousness in Dickens's Esther". Nineteenth-Century Fiction, Berkely (in 275 sq). Berkely: University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Kilian, Crawford (1974). "In Defence of Esther Summerson". Dickensian Review. 54: 318–328.

- Eggert, Paul (1980). "The Real Esther Summerson". Dickens Studies Newsletter. 11: 74–81.

- Moseley, Merritt (1985). "The Ontology of Esther's Narrative in Bleak House". South Atlantic Review. South Atlantic Modern Language Association.

- Eldredge, Patricia R.; Paris, B. J. (1986). "The Lost Self of Esther Summerson, a Horneyan Interpretation of Bleak Hous". Third force psychology and the study of literature. Rutherford N. J: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Frank, Lawrence (1975). "Through a Glass Darkly, Esther Summerson and Bleak House". Dickens Studies Annual. 4. Brooklyn: AMS Press, Inc.: 92 sq.

- Salotto, Eleanor (1997). "Detecting Esther Summerson's Secrets: Dickens's Bleak House of Representation". Victorian Literature and Culture. 25 (2): 333–349. doi:10.1017/S1060150300004824.

- Matsuura, Harumi (2005). "The Survival of an Injured Daughter: Esther Summerson's Narration in Bleak House". Kawauchi Review (4): 60–79.

- Barker, Daniel K (2009). A justification of the narrative presence of Esther Summerson in Charles Dickens's Bleak House. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW).