Denmark–Iceland relations

| |

Denmark |

Iceland |

|---|---|

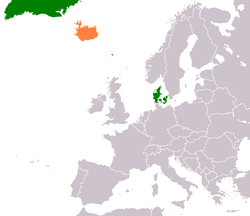

Denmark–Iceland relations are the diplomatic relations between Denmark and Iceland. Both countries are full members of the Council of the Baltic Sea States, Nordic Council, NATO, and Council of Europe. Denmark has an embassy in Reykjavík, while Iceland has an embassy in Copenhagen and consulates-general in Nuuk, Greenland and in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.[1][2]

History

[edit]Danish rule in Iceland (1383–1944)

[edit]

From 1383 until the establishment of the Icelandic republic in 1944, Denmark and Iceland shared a long and intertwined history. Over these centuries, Danes and Icelanders interacted both directly and indirectly, particularly through Copenhagen, which served as the administrative hub and cultural center for Icelanders—especially via the University of Copenhagen, which was their main institution of higher learning until the University of Iceland was founded in 1911. Danish interest in Icelandic medieval literature led to scholarly cooperation, and Danish merchants and officials were active in Iceland for centuries. These contacts fostered cultural exchanges where Danish language and customs became influential. Until the late 19th century, Iceland was largely a rural, agrarian society, marked by traditional ways of life and a strong oral storytelling culture. Towns began to form only after 1800, often around harbors, and these new urban centers brought together Danish merchants, craftsmen, and officials with Icelanders. Danish officials administered Iceland under absolutist rule from 1662 onward, with most senior posts initially filled by Danes and later by educated Icelanders. Many of these elites had studied in Denmark and adopted Danish culture, with Danish serving as the language of administration and high society. Danish merchants held significant economic power, especially after 1786 when only Danish subjects were allowed to trade with Icelanders, and towns like Reykjavik gained market rights. Despite occasional tensions, Danish traders often held respected positions in society. Reykjavik, in particular, developed quickly into the most important city on the island, partly due to early industrial efforts led by figures like Skúli Magnússon. As industries grew, Icelanders traveled to Denmark for vocational training, while Danish artisans settled in Iceland. The medical field also saw Danish involvement, including the arrival of trained professionals such as midwives. This created a Danish-influenced elite whose language and lifestyle contrasted with the broader rural population. While official and elite Icelandic often incorporated Danish vocabulary and structures, everyday speech and folk culture remained rooted in native traditions, largely free of foreign influence. This divergence eventually led to a cultural divide between the traditional rural populace and the urban, Danish-influenced elite.[3]

Church

[edit]The strong ties between Iceland and Denmark after the Reformation left a clear mark on Icelandic church culture and hymn tradition. Although Iceland had a long-standing religious and linguistic tradition, Danish influence became particularly significant through the use of Danish and German hymn texts as translation sources. Many Icelandic hymns, especially in the early Protestant period, were shaped by Danish intermediaries, both linguistically and stylistically. Over time, a growing national consciousness led to an increased emphasis on uniquely Icelandic expressions of faith, culminating in more original hymn production in the 19th century. Nonetheless, the legacy of Danish church influence remains evident in its hymn heritage today.[4] The confirmation decree of 1741 and the use of the catechism of Erik Pontoppidan marked a shift in religious education in Iceland. Danish church officials, especially Ludvig Harboe, introduced reforms in line with pietist ideals, including regulations promoting moral discipline and Christian instruction in households. This led to improved literacy but also restrictions on traditional Icelandic literature. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Danish theological texts played a major role in Icelandic religious life, until local education efforts, such as Helgakver by Helgi Hálfdanarson and the establishment of the seminary in Reykjavik, gradually localized theological instruction.[5] A number of prominent priests in Iceland were educated in Denmark, where they became acquainted with the practices of the Danish church. While it had previously been possible to become a priest in Iceland without a formal theological degree, a decree in 1633 gave preference to those who had studied at the University of Copenhagen when assigning church positions. As a result, Danish-trained clergy often filled the most influential roles. During the 17th century, about 175 Icelandic students enrolled at the university, the majority pursuing theological studies. Of those who completed their education before 1700, two-thirds became priests, bishops, or rectors, which further strengthened the Icelandic connection to the Danish church. In addition to religious texts for the general public, Christian dogma was also spread through the works of Danish theologians, leaving a lasting influence on both the church and Icelandic intellectual life. Translations of key theological works, including those by Christian Bastholm and Jacob Peter Mynster, had a significant impact, and the writings of Mynster were widely circulated. With the establishment of a theological seminary in Reykjavik in 1847, fewer Icelanders traveled to Denmark for their studies, although Danish theological works continued to influence the Icelandic church.[6]

Path to independence and language shift (1874–1944)

[edit]Iceland began its journey toward self-rule with the introduction of its first constitution in 1874, followed by home rule in 1904, and full sovereignty in 1918 when it became a free state in personal union with Denmark. The establishment of the University of Iceland in 1911 marked a significant step, as it gradually took over the role once held by the University of Copenhagen as the premier center of learning for Icelanders. Despite this, many Icelanders continued to study in Denmark, and even today, Denmark remains the country where most Icelanders seek higher education outside of their country. During the independence movement around 1900, attitudes towards the Danish language shifted, and political divisions emerged over its role in Icelandic society. Criticism was particularly directed at the prevalence of Danish in spoken Icelandic and the use of Danish literary works over traditional Icelandic sagas. As a result, schools were encouraged to reduce Danish instruction, though it remained a subject in secondary education. Notably, Jónas Jónsson, a prominent figure in this debate, became an influential politician and education minister. While the push for greater independence was led by Icelanders, Danish influence remained strong. Holger Wiehe, the first Danish lecturer at the University of Iceland, played a key role in the cultural and political landscape in Iceland, advocating for Icelandic sovereignty and contributing to the creation of an Icelandic-Danish dictionary. With increasing independence, the presence of Danes in Iceland diminished, and the role of Danish in daily life gradually decreased. Nonetheless, Danish culture continued to have a lasting impact, with many Icelandic youth still traveling to Denmark for education or work.[7]

Denmark recognized the independence of Iceland on 1 December 1918 and the two countries remained in personal union until 1944 as part of the Danish–Icelandic Act of Union.[8] While in union with Denmark, the diplomatic relations of Iceland with the rest of the world were handled by Denmark.[9] Denmark opened their embassy in Reykjavík on 4 August 1919 with Johannes Erhardt Bøggild appointed as ambassador, while Iceland opened their embassy in Copenhagen on 16 August 1920 with Sveinn Björnsson as ambassador. The Icelandic embassy was temporarily closed from 1924 to 1926 due to financial costs.[10] King Christian X visited Iceland on 26 June 1921.[10]

Independence and NATO (1940–1949)

[edit]Iceland became fully independent from Denmark on 17 June 1944 during the German occupation of Denmark, as diplomatic relations between the two countries were suspended.[9][11]

During the early years of World War II, the occupation of Denmark by Nazi Germany had significant implications for the relationship of Iceland with Denmark and the broader international community. With Denmark unable to fulfill its obligations under the Danish–Icelandic Act of Union. Iceland asserted its sovereignty and began managing its own foreign affairs. Although Iceland initially sought to maintain strict neutrality, the increasing strategic importance of the country led to British and later American involvement. As Iceland was left with no choice but to abandon its neutrality, discussions about severing ties with Denmark emerged, with many Icelanders arguing that the country should become fully independent. The issue of independence was complicated by the moral hesitation to break ties with Denmark while it was in a weakened state. Ultimately, the decision to enter into the 1941 defense agreement with the United States marked the first significant foreign policy shift of Iceland, further distancing the country from Denmark and cementing its path toward full independence.[12]

After the war, Denmark and Norway discussed forming a Scandinavian defence union, which worried Iceland as if it was to be excluded, it would isolate the country and hinder cooperation with its Nordic neighbors. When Denmark and Norway thus chose to join NATO, Iceland followed suit. Prime Minister Stefánsson had a correspondence with Danish Prime Minister Hedtoft which revealed the tension Iceland faced, as joining NATO was seen as necessary for security but could distance the country from Denmark and Norway, if they refrained from joining.[13]

Return of Icelandic works

[edit]From September 1945 on, Iceland demanded the return of the sagas and codexes, which Árni Magnússon had collected and brought to University of Copenhagen.[14] Between 1971 and 1992, Denmark returned thousands of works to Iceland including the Codex Regius and Flateyjarbók.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "Embassy of Denmark in Reykjavík". Archived from the original on 2022-03-26. Retrieved 2022-03-27.

- ^ "Embassy of Iceland in Copenhagen". Archived from the original on 2020-09-21. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ Hauksdóttir, Auður (2011). "Danske minder i Island: Om mødet mellem dansk og islandsk kultur". Danske Studier: 5–11.

- ^ Hauksdóttir, Auður (2011). "Danske minder i Island: Om mødet mellem dansk og islandsk kultur". Danske Studier: 11–13.

- ^ Hauksdóttir, Auður (2011). "Danske minder i Island: Om mødet mellem dansk og islandsk kultur". Danske Studier: 14.

- ^ Hauksdóttir, Auður (2011). "Danske minder i Island: Om mødet mellem dansk og islandsk kultur". Danske Studier: 15.

- ^ Hauksdóttir, Auður (2011). "Danske minder i Island: Om mødet mellem dansk og islandsk kultur". Danske Studier: 40–43.

- ^ Gaebler, Ralph; Shea, Alison (6 June 2014). Sources of State Practice in International Law: Second Revised Edition. p. 177. ISBN 9789004272224.

- ^ a b Halldór Ásgrímsson (2000). "Ljósmyndasýning í tilefni af 60 ára afmæli utanríkisþjónustunnar 10. apríl 2000" (PDF) (in Icelandic). p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ a b Halldór Ásgrímsson (2000). "Ljósmyndasýning í tilefni af 60 ára afmæli utanríkisþjónustunnar 10. apríl 2000" (PDF) (in Icelandic). p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Lidegaard, Bo (2001). Dansk udenrigspolitiks historie: Overleveren 1914-1945 (in Danish). Vol. 4. Danmarks Nationalleksikon. p. 409.

- ^ Bjorgulfsdottir, Margret (1989). "The Paradox of a Neutral Ally: A Historical Overview of Iceland's Participation in NATO". The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs. 13 (1): 73–76. JSTOR 45289776.

- ^ Bjorgulfsdottir, Margret (1989). "The Paradox of a Neutral Ally: A Historical Overview of Iceland's Participation in NATO". The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs. 13 (1): 80–81. JSTOR 45289776.

- ^ Mentz, Søren (9 October 2019). "Jo mere Danmark føjede sig, jo mere ønskede Island selvstændighed fra kongeriget". Politiken (in Danish).

- ^ "Danmark leverede kulturskatte tilbage i tusindvis". DR (in Danish). 14 September 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2023.