Yosef Haim Brenner

Joseph Chaim Brenner | |

|---|---|

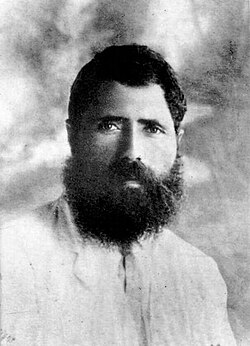

Brenner in 1910 | |

| Native name | יוסף חיים ברנר |

| Born | 11 September 1881 Novi Mlyny, Russian Empire |

| Died | 2 May 1921 (aged 39) Jaffa, Mandatory Palestine |

| Language | Hebrew |

| Spouse |

Chaya Braude (m. 1913) |

Joseph Chaim Brenner (Hebrew: יוסף חיים ברנר, romanized: Yosef Ḥayyim Brener; 11 September 1881 – 2 May 1921) was a Hebrew-language author from the Russian Empire, and one of the pioneers of modern Hebrew literature, a thinker, publicist, and public leader. In addition to his literary innovations and contributions, Brenner gained a reputation for his ascetic lifestyle and his courage to challenge social conventions, evident in his distinctive expressions such as "Nevertheless" and "The right to shout." These qualities, along with his tragic death during the 1921 riots, created a legendary aura around him, making him an almost mythical figure in the history of literature and culture in the Land of Israel.

Biography

[edit]

Yosef Haim Brenner was born to a poor Jewish family in Novi Mlyny, Russian Empire (today part of Ukraine). He studied at a yeshiva in Pochep, and published his first story, Pat Lechem ("A Loaf of Bread") in Ha-Melitz in 1900, followed by a collection of short stories in 1901.[1]

In 1902, Brenner was drafted into the Russian army. Two years later, when the Russo-Japanese War broke out, he deserted. He was initially captured, but escaped to London with the help of the General Jewish Labor Bund, which he had joined as a youth.

In 1905, he met the Yiddish writer Lamed Shapiro. Brenner lived in an apartment in Whitechapel, which doubled as an office for HaMe'orer, a Hebrew periodical that he edited and published in 1906–07. In 1922, Asher Beilin published Brenner in London about this period in Brenner's life.

In 1913, Brenner married Chaya Braude, with whom he had a son, Uri.[2]

Brenner immigrated to Palestine (then part of the Ottoman Empire) in 1909. He worked as a farmer, eager to put his Zionist ideology into practice. Unlike A. D. Gordon, however, he could not take the strain of manual labor, and soon left to devote himself to literature and teaching at the Gymnasia Herzliya in Tel Aviv. According to biographer Anita Shapira, he suffered from depression and problems of sexual identity.[2] He was murdered in Jaffa in May 1921 during the Jaffa riots.

Zionist views

[edit]Brenner immigrated to the Land of Israel in 1909 and became one of the prominent figures of the Second Aliyah. At first, he aspired to work in agriculture in order to physically embody the Zionist ideal. However, unlike his friend and mentor A.D. Gordon, Brenner could not withstand the demands of farm labor and abandoned it after a week (some say he was forced to) in favor of less physically demanding work. Until 1914, he lived in Jerusalem, in the Ezrat Yisrael neighborhood, in a rented, monastic-style room near the Ahdut printing press. He was a member of the editorial board of the newspaper HaAhdut and published articles in other newspapers as well.

In his writing, Brenner praised the Zionist endeavor, though also affirmed that the Land of Israel was just another diaspora and no different from other diasporas - which of course happened to be the case at the time under the british mandate.[2]

Writing style

[edit]Brenner was very much an "experimental" writer, both in his use of language and in literary form. With Modern Hebrew still in its infancy, Brenner improvised with an intriguing mixture of Hebrew, Aramaic, Yiddish, English and Arabic. In his attempt to portray life realistically, his work is full of emotive punctuation and ellipses. Robert Alter, in the collection Modern Hebrew Literature, writes that Brenner "had little patience for the aesthetic dimension of imaginative fictions: 'A single particle of truth,' he once said, 'is more valuable to me than all possible poetry.'" Brenner "wants the brutally depressing facts to speak for themselves, without any authorial intervention or literary heightening."[3] This was Alter's preface to Brenner's story, "The Way Out", published in 1919, and set during Turkish and British struggles over Palestine in World War I.

The Brenner Affair

[edit]At the end of 1910, Brenner published an article in the newspaper HaPoel HaTza'ir that sparked a wide public controversy, later known as "The Brenner Affair." The article offended the sensibilities of religious and traditional communities both in the Land of Israel and abroad. On the one hand, it contained a blunt and dismissive rejection of all religions, including Judaism; on the other hand, it expressed allegiance to Jewish culture, which Brenner saw as rooted in both the Old Testament and the New Testament. The uproar that followed did not subside for many months. The “Odessa Committee” ceased its financial support of the newspaper HaPoel HaTza'ir, and in response, writers and workers from the Land of Israel rallied together and donated to ensure the paper's continued existence. The debates expanded in various directions, and hundreds of articles and letters were published in journals both in the Land of Israel and throughout the Diaspora concerning the affair and its aftermath.[4]

Even after the controversy subsided and gave way to other disputes, the "event" continued to impact Brenner’s life. For example, when he began teaching literature at the Herzliya Gymnasium in 1915, his appointment faced opposition from the school’s supervisory board. As a compromise, a special instructor was assigned to oversee Brenner’s classes to ensure he followed the curriculum and did not incite against religion. Eventually, Brenner's teaching was found to be excellent and entirely appropriate, and he continued teaching at the Gymnasium, including Bible, Mishnah, and Hebrew language.[citation needed]

Literary activity

[edit]As part of his literary activity, Brenner played a key role in launching S.Y. Agnon into the Jewish literary and cultural consciousness by helping to publish his book And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight.

He translated from Russian into Hebrew Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Tolstoy’s Master and Man, and from German into Hebrew two books by Gerhart Hauptmann as well as The Jews of Today by Arthur Ruppin. He also engaged in translating works of popular science.

In 1913, Brenner married kindergarten teacher Chaya Broide, and a year later their only son was born. Brenner named him Uri Nissan, after his friend Uri Nissan Gnessin, who had died about a year earlier. The marriage did not last long, and his wife left him, taking their son with her to Berlin.[citation needed]

In 1917, during the expulsion of Tel Aviv, when the Ottoman authorities expelled the residents of Tel Aviv and the Jewish residents of Jaffa, Brenner relocated to Hadera, returning to Jaffa only after the British conquest of the region.

From 1919, he edited the literary monthly HaAdamah (the Land in Hebrew), which was published as an appendix to Kuntres, edited by Berl Katznelson.

Brenner was also a lecturer and teacher in the roadwork camps of the Yosef Trumpeldor Labor Battalion and was described as one of the most passionate and inspiring advocates for the unification of the workers' parties in the Land of Israel.

Commemoration

[edit]The site of his murder on Kibbutz Galuyot street is now marked by Brenner House, a center for Hanoar Haoved Vehalomed, the youth organization of the Histadrut. Kibbutz Givat Brenner was also named for him, while kibbutz Revivim was named in honor of his magazine. The Brenner Prize, one of Israel's top literary awards, is named for him.[5]

Published works

[edit]- Me-ʻemek ʻakhor: tsiyurim u-reshimot [Out of a Gloomy Valley]. Warsaw: Tushiyah. 1900. A collection of 6 short stories about Jewish life in the diaspora.

- Ba-ḥoref [In Winter] (novel). Ha-Shilo'aḥ. 1904.

- Yiddish: Warsaw, Literarisher Bleter, 1936.

- Mi-saviv la-nekudah [Around the Point] (novel). Ha-Shilo'aḥ. 1904.

- Yiddish: Berlin, Yiddisher Literarisher Ferlag, 1923.

- Me'ever la-gvulin [Beyond the Border] (play). London: Y. Groditzky. 1907.

- Min ha-metzar [Out of the Depths] (novella). Ha-Olam. 1908–1909.

- Bein mayim le-mayim [Between Water and Water] (novella). Warsaw: Sifrut. 1909.

- Kitve Y. Ḥ. Brenner [Collected Works]. Kruglyiakov. 1909.

- Atzabim [Nerves] (novella). Lvov: Shalekhet. 1910.

- English: In Eight Great Hebrew Short Novels, New York, New American Library, 1983.

- Spanish: In Ocho Obras Maestras de la Narrativa Hebrea, Barcelona, Riopiedras, 1989.

- French: Paris, Intertextes, 1989; Paris, Noel Blandin, 1991.

- Mi-kan u-mi-kan: shesh maḥbarot u-miluʼim [From Here and There] (novel). Warsaw: Sifrut. 1911.

- Sipurim [Stories]. Sifriyah ʻamamit; no. 9. New York: Kadimah. 1917. hdl:2027/uc1.aa0012503777.

- Shekhol ve-khishalon; o, sefer ha-hitlabtut [Breakdown and Bereavement] (novel). Hotsaʼat Shtibel. 1920.

- English: London, Cornell Univ. Press, 1971; Philadelphia, JPS, 1971; London, The Toby Press, 2004.[6]

- Chinese: Hefei, Anhui Literature and Art Publishing House, 1998.

- Kol kitve Y. Ḥ. Brenner [Collected Works of Y. H. Brenner]. Tel Aviv: Hotsaʼat Shtibel. 1924–30.

- Ketavim [Collected Works] (four volumes). Ha-kibutz ha-me’uhad. 1978–85.

- English: Colorado, Westview Press, 1992.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Shaked, Gershon (2007). "Brenner, Joseph Ḥayyim". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 1347. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ a b c Golan, Avirama (2008-09-18). "The Case of Y. H. Brenner". Haaretz. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ^ Alter, Robert (1975). Modern Hebrew Literature. New York: Berhman House. p. 141.

- ^ "מאורע ברנר / נורית גוברין - פרויקט בן־יהודה". benyehuda.org. Retrieved 2025-05-25.

- ^ Sela, Maya (14 April 2011). פרס ברנר יוענק השנה לסופר חיים באר [Brenner Prize awarded this year to writer Haim Beer]. Haaretz (in Hebrew). Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "Breakdown and Bereavement by Y. H. Brenner". The Toby Press. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved 2013-12-16.

Further reading

[edit]- Shapira, Anita (2014). Yosef Haim Brenner: A Life. Tr. Antony Berris. Stanford. California: Stanford University Press.

- Yosef Haim Brenner: A Biography (Brenner: Sippur hayim), Anita Shapira, Am Oved (in Hebrew)

- Yosef Haim Brenner: Background, David Patterson, Ariel: A Quarterly Review of Arts and Letters in Israel, vol. 33/34, 1973

External links

[edit]- Brenner's Hebrew works in Project Ben-Yehuda

- Institute for Translation of Hebrew Literature bio

- Works by or about Yosef Haim Brenner at the Internet Archive

- Works by Yosef Haim Brenner at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1881 births

- 1921 deaths

- Burials at Trumpeldor Cemetery

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the Ottoman Empire

- Jews from Ottoman Palestine

- Modern Hebrew writers

- People from Chernihiv Oblast

- People from Chernigov Governorate

- 20th-century Ukrainian Jews

- Jewish writers from the Russian Empire

- Immigrants of the Second Aliyah

- People murdered in Mandatory Palestine