Walther von Klingen

Walther von Klingen (died 1 March 1284) was a nobleman from the Thurgau area. After the death of his three sons made it impossible for him to establish a dynasty, he became a benefactor of the church. He founded a monastery in Wehr that later moved to Basel and donated generously to several monastic orders. He later became a close associate and supporter of King of Germany Rudolf von Habsburg. Walther reportedly foresaw the election of Rudolf as King in a dream vision. He later spent time at Rudolf's court and lent him a large sum of money, receiving the right to collect imperial taxes from the city of Zurich in return. At the end of his life, Walther lived in Basel, where he and his wife are buried in the Klingental monastery.

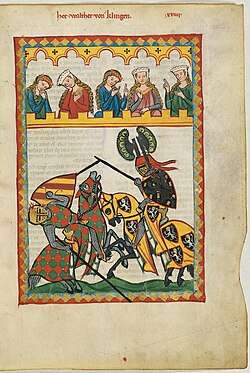

Eight of his songs, which belong to the Middle High German Minnesang tradition, has been preserved in the Codex Manesse manuscript. They are conventional canzone songs with typical Minnesang themes like lamentation or courtship.

Family background

[edit]

Walther III von Klingen was born c. 1220.[1][2] He came from an old Thurgau family, originating in the Altenburg near Märstetten.[3] Around 1200, the family split into two branches.[3] The elder line moved to Altenklingen, whose foundations were subsumed into Altenklingen Castle, while the younger line moved to Hohenklingen Castle.[3][4]

Walther's parents were Ulrich II von Altenklingen and Ita von Tegerfelden; they had three sons, Ulrich III, Walther III and Ulrich Walther, and two daughters, Ita and Williburg.[5][6] Ulrich Walther was the youngest son and there are reasons to believe Walther was the oldest.[7][a] Ulrich II participated in the Sixth Crusade led by Frederick II, returning in 1229.[9]

After the death of Ita's father Walther von Tegerfelden c. 1236, she inherited a large estate.[1] Ulrich II used her fortune to found the city of Klingnau on land he had exchanged with Saint Blaise Abbey in 1239. He then built Klingnau Castle and lived there.[10] The document certifying this exchange, dated 26 December 1240, contains the first mention of Walther and his brother Ulrich.[11][9][12] Walther's parents died in 1249.[13] The family estate was split between Walther and his brother, which was finalised in a 1253 contract. Walther also gained ownership of some of his mother's inheritance.[14][15]

Life

[edit]

At some point no later than 1249, Walther married Sophia, a noblewoman whose family background is uncertain.[16][b] By 1252, they had four children: the sons Walther, Ulrich and Hermann and a daughter called Agnes.[19] Four more daughters were born later: Verena, Herzelauda,[c] Katharina and Klara.[19][20] The sons Walther and Hermann died before 1256, Ulrich before 1260, and the daughter Verena died before 1265.[21] With no surviving sons, Walther could no longer continue his dynasty.[22][14]

In 1256, he donated some land in Wehr to a convent of Dominican nuns that had been founded in Häusern by members of the Horburg family.[23] The nuns moved in 1259 to the new monastery, which became known as Klingental.[24] The Klingental monastery moved to Kleinbasel (now part of Basel) c. 1274.[25][26] He generously donated land to religious orders. This included donations to Saint Blaise Abbey in 1257, to the Teutonic Order at Beuggen Castle and to the Knights Hospitaller in Klingnau in 1267, and to the Hermits of Saint William on several occasions after founding Sion monastery in Klingnau in 1269.[22][27] Walther sold his Herrschaft at Klingnau and some other possessions to Eberhard, Bishop of Constance, for 1100 mark silver in 1269.[22] Walther's daughters Herzelauda and Katharina were married to Reichsvogts Ludwig and Rudolf of the Lichtenberg family of Strasbourg.[20] Walther exchanged some of his properties for lands in the Alsace region and moved to Strasbourg in 1271.[22] Rudolf and Herzelauda both died c. 1272.[22][20] Between 1274 and 1278, Walther sold his Alsatian possessions again and returned to Klingnau, where he still had living quarters in the castle.[22]

From at least 1256, Walther was in contact with Rudolf von Habsburg.[28] He acted as arbitrator for two disputes involving Rudolf's appropriation of lands from the inheritance of Hartmann IV von Kyburg.[29] Walther and Rudolf have been described as close friends or possibly related through Walther's wife Sophia, but the historian Christopher Schmidberger considered the evidence for either of these claims inconclusive.[30] The Dominican chronicler of Colmar reports that Walther had a dream vision of Rudolf's election as King of Germany. In the dream, the nobles and electors of the realm are gathered to discuss the election, with the crown in the centre of the room. They decide that the person who is able to pick up the crown should become king. Nobody is able to lift the crown until Rudolf steps up and crowns himself.[31] Rudolf was elected on 1 October 1273, and Walther spent some time at his court in the following years.[20] From various documents involving Rudolf, it can be inferred that Walther was involved in the itinerant court's activities in the Upper Rhine and Alsace areas, but not in other parts of the Empire.[32][33] The Dominican chronicler's report of a discussion between Rudolf and Walther in Mainz in 1276, shortly before Rudolf's war against Ottokar II of Bohemia, is viewed as fictitious by the historian Christoph Schmidberger.[34] In 1283, the king had a debt of 1100 marks silver to Walther; to repay it, Walther was granted the right to collect the imperial taxes from the city of Zurich.[35][20]

Towards the end of his life, possibly from 1281, Walther lived in a house in Basel.[20] He made his last will and testament in Klingnau in 1283 and finalised his will in Basel in documents dated 26 and 28 February 1284.[32][36] His wife Sophia, who became responsible for Walther's possessions, continued to donate generously. She died in 1291; both were buried in the Klingental monastery in Basel.[32]

Poetry

[edit]Eight of Walther's Minnesang songs were preserved in the Codex Manesse manuscript.[37][2] In the corresponding miniature, Walther is shown as the victor of a joust, bearing the Altenklingen coat of arms.[38][39] His poetry has been described as "not worthy of special praise"[40] and he is considered only a "minor" poet.[37] The known poems are conventional songs with themes of lamentations, courtship or general praise of women,[41] and show influences of Gottfried von Neifen and Konrad von Würzburg.[40][42] All of the songs are in the canzone style and date from Walther's time in Klingnau, before 1271.[2][43]

Walther's poem "Swie dú zit sich wil verkeren" was included in a selection of Minnesang poetry by Johann Jakob Bodmer.[44] In a rendering of this poem as "Wie sich die Zeit will enden, wenden", the Romantic author Clemens Brentano imitated both the form and the content of Walther's original.[45][46]

Notes

[edit]- ^ A document from 1249 relating to a donation after the death of Ulrich II and his wife carries only the seal of Walther, indicating that his brothers did not yet possess seals, while a document from 1253 carries the seals of Walther and Ulrich III.[8]

- ^ In the 19th and 20th centuries, several authors claimed that Sophia was a member of the House of Frohburg, but there is no supporting evidence.[17] The historian Erik Beck speculates that she could have been related to the Horburg family.[18]

- ^ Herzelauda may have been named after Herzeloyde, the mother of Parzival, indicating Walther's interest in literature.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Valenta 2010, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Hofert 2023.

- ^ a b c Beck 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Grabowsky 2023.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Bartsch 1886, p. LXXX.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Beck 2010, p. 49.

- ^ a b Bartsch 1886, p. LXXXI.

- ^ Valenta 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Beck 2015, p. 250.

- ^ Huber 1878, p. 4.

- ^ Beck 2015, p. 249.

- ^ a b Schiendorfer 2011.

- ^ Bartsch 1886, pp. LXXXI–LXXXII.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 53, 67–68.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Beck 2010, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f Schiendorfer 2012, p. 647.

- ^ Beck 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e f Valenta 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Beck 2010, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Werthmüller 1980, p. 61.

- ^ Bartsch 1886, p. LXXXII.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, p. 31.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, pp. 35–41.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Valenta 2010, p. 22.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Schmidberger 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Schiendorfer 2012, pp. 647–648.

- ^ a b Garland & Garland 1997.

- ^ Bartsch 1886, pp. LXXXIV–LXXXV.

- ^ Schiendorfer 2012, pp. 646–647.

- ^ a b Wilmanns 1882.

- ^ Händl 2012.

- ^ Bartsch 1886, p. LXXXV.

- ^ Virchow 2002, p. 276.

- ^ Frühwald 1977, p. 64.

- ^ Storz 1972, p. 142.

- ^ Gentry 2020, p. 293.

Sources

[edit]

- Bartsch, Karl (1886). Die Schweizer Minnesänger (in German). Frauenfeld: J. Huber.

- Beck, Erik (2010). "Walther von Klingen, Wehr und die Verlegung des Klosters Klingental". In Stadt Wehr (ed.). Walther von Klingen und Kloster Klingental zu Wehr (in German). Ostfildern: Thorbecke. pp. 47–76.

- Beck, Erik (2015). "Die Burgen Klingnau und Wehr als Sitze des edelfreien Geschlechts derer von Klingen - Überlegungen zu ihrer Rolle für die Herrschaftsausübung". Burgen und Schlösser (in German). 56: 249–258 – via academia.edu.

- Frühwald, Wolfgang (1977). Das Spätwerk Clemens Brentanos : (1815-1842) : Romantik im Zeitalter d. Metternich'schen Restauration. Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 978-3-484-15033-1.

- Garland, Henry; Garland, Mary (1997). Garland, Henry; Garland, Mary (eds.). "Walther von Klingen". The Oxford Companion to German Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 956. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198158967.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-815896-7. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Gentry, Francis G. (15 September 2020). "Medievalism as an Instrument of Political Renewal in Nineteenth-Century Germany". The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Medievalism. Oxford University Press. pp. 289–302. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199669509.013.18. ISBN 978-0-19-966950-9.

- Grabowsky, Inka (20 November 2023). "Schöner Wohnen im Mittelalter: Zu Besuch im Schloss Altenklingen". Magazin (in German). Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- Händl, Claudia (2012). "Walther von Klingen". Killys Literaturlexikon (in German). De Gruyter.

- Hofert, Sandra (13 September 2023). "Walther von Klingen". www.ldm-digital.de (in German). Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- Hoffmann, Werner (1989). "Minnesang in der Stadt". Mediaevistik (in German). 2: 185–202. ISSN 0934-7453. JSTOR 42584351.

- Huber, Johann (1878). Die Regesten der ehemaligen Sankt Blasier Propsteien Klingnau und Wislikofen im Aargau: ein Beitrag zur Kirchen- und Landesgeschichte der alten Grafschaft Baden (in German). Luzern: Räber.

- Schiendorfer, Max (17 March 2011). "Klingen, Walther von". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Schiendorfer, Max (2012). "Walther von Klingen". In Stöllinger-Löser, Christine (ed.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon (in German). Vol. 10. pp. 646–650. ISBN 9783110156065.

- Schmidberger, Christopher (2010). "Ungleicher Freund oder Vasall?: Das persönliche Verhältnis zwischen Walther von Klingen und Rudolf von Habsburg". In Stadt Wehr (ed.). Walther von Klingen und Kloster Klingental zu Wehr (in German). Ostfildern: Thorbecke. pp. 23–46.

- Storz, Gerhard (1972). Klassik und Romantik.

- Valenta, Reinhard (2010). "Walther von Klingen: Eine biographische Skizze". In Stadt Wehr (ed.). Walther von Klingen und Kloster Klingental zu Wehr (in German). Ostfildern: Thorbecke. pp. 19–22.

- Virchow, Corinna (2002). "Der "Basler Dialog zwischen Seele und Leib"". Medium Ævum (in German). 71 (2): 269–285. doi:10.2307/43630436. ISSN 0025-8385. JSTOR 43630436.

- Werthmüller, Hans (1980). Tausend Jahre Literatur in Basel (in German). Basel: Birkhäuser. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-6561-6.

- Wilmanns, Wilhelm (1882). "Klingen, Walther von". Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German). Vol. 16. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. p. 189.