User:Ana D. Voicu/sandbox

Colonialism in the Baltic States

[edit]

The Baltic states, also known as the Baltics, consist of the countries Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania and are located on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea. Tsarist Russia had a history of occupation in the Baltics that predated the 20th Century. In the summer of 1940, the Soviet Union occupied the independent republics of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.[1] This military occupation of the Baltic states, less frequently referred to and understood as colonialism persisted from 1940 until 1991.[2] Soviet colonialism enforced oppressive strategies according to region, and the Baltic states shared proximate experiences.[3] For example, within the context of broader Soviet colonialism, the Baltic states each had periods of independence between 1920 and 1940 and were framed as more “Western” than other Soviet states due to their economic capabilities. [4] [5]

This article will refer to colonization and occupation interchangeably, as does Estonian scholar Epp Annus.[6]

The Soviet Union as a Colonial Power

[edit]

As it occupied, the Soviet Union simultaneously presented itself as a liberatory, post-colonial federation for those who had previously been subjected, against their will, to the Tsarist empire.[8] [9] The USSR’s colonial mechanisms did not neatly align with Western imperialism mechanisms, which concealed racism and Orientalism, obstructing the recognition of the USSR as a colonial entity. [10] Additionally, the Soviet colonization of the Baltic states differed from the dominant paradigm of colonialism, i.e., they were modern nation-states, and colonization as a justification to combat "barbarism" was inadequate. [11] In the 1960s, the majority of the international community recognized the illegal annexation of the Baltic states but did not legally recognize them as "de jure colonized countries”. [12] The Russian national memory affirms the validity and glory of the Soviet Union as an occupying colonial power; there is a yearning for the previous empire where a collective Russian identity triumphed and was welcomed, according to a Russian perspective, in the Baltic states. [13] The discourse concerning Soviet colonization is complex because it is not always recognized as colonialism: the Soviet Union has an “unconvential imperial–colonial history”. [14] As the Russian occupation of Ukraine persists, the Baltic states have been forced to contend with their colonial histories.[15][7] Madina Tlostanova, a decolonial scholar, suggests the concept of global coloniality to capture the nuance of post-Soviet and Soviet colonial realities and their epistemological effects in the neo-liberal global order and post-colonial academia. [16]

Estonia

[edit]

Estonia has a rich history full of Vikings and crusades. The trade between western Europe and eastern Europe and further east has been passing through the Baltic sea. On one hand this led to wealth, but it led to war on the other [17].

18th and 19th century

[edit]In the 17th century, Estonia belonged to Sweden until the Great Nordic War (1700-1721), a war about power around the Baltic Sea. Sweden lost to Russia, and Estonia became a Russian region [18] . Estonians were mostly farmers and the underclass of society. In the 19th century, nationalism rose in Estonia. As a protest against the growing power of the Lutheran church, Estonians gained national consciousness and to the development of the Estonian national language, which is really important for gaining more power and for forming borders [19]

20th century

[edit]Following the February Revolution (1917) in Russia, Estonia gained more power. After the October Revolution, Estonia sought to become entirely independent from Russia [20]. During the next two years, Estonians fought for their freedom in the Estonian War of Independence. Estonia fought against the Red Soviet army and the German army. Estonia signed the Tartu Peace Treaty on February 2, 1920, in which the Soviet Union recognized Estonia's independence. During the twenty years of Estonian independence, Estonia got a democratic constitution and a cultural Estonian renaissance with a focus on Estonian art and language emerged. But there were also challenges, such as political turbulence and issues on agricultural reclassification.

In 1940, right at the beginning of world war two, the Soviet Union conquered Estonia. In 1941 Germany took Estonia from Russia. And in 19444 the Soviet Union conquered Estonia again. From then on, Estonia was governed by the Soviet Union. This was the beginning of Russian colonialism in Estonia [21]. Between 1945 and 1990, Estonia belonged to the Soviet Union as the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (ESSR) [22]. Estonia became a communist country and was collectivized, suppressed of religion and national identity, and those who protested were deported to Siberia. After the death of Stalin, Khrushchev introduces the "Khrushchev Thaw" in 1956, which was more relaxed than Stalins regime. But the Soviets still remained in power. The Soviets brought heavy industry to Estonia, and large numbers of Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian immigrants started to work in the Estonian industry. Under Gorbachev’s leadership from 1987, a period of reforms started in the Soviet empire: Glasnost and Perestroika. The road to independence. In 1989, the Baltics organised the “Baltic Way”, a chain of 2 million people, symbolizing their wish to be independent. In 1990 Estonia held its first free elections and in 1991, Estonia regained independence which put an end to Soviet colonisation in Estonia.

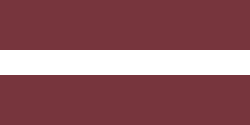

Latvia

[edit]18th Century

[edit]

Following the Treaty of Nystad (1721), which ended the Great Northern War, Russia annexed Livonia, encompassing modern Latvia and Estonia, from Sweden. This marked the beginning of over two centuries of Russian dominance. However, Latvia remained divided. While northern Livonia was under Russian control, southern Livonia, Courland, and Latgale remained under Polish-Lithuanian rule, reflecting earlier partitions.[23] This dual structure lasted until the Third Partition of Poland (1795), when Catherine II annexed Courland, fully integrating Latvia into the Russian Empire and ending Polish-Lithuanian influence.[24]

19th Century

[edit]Throughout the 19th century, Latvia was ruled by four Russian Tsars: Alexander I, Nicholas I, Alexander II, and Alexander III. Later, Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917). Under Alexander I (1801-1825), who considered himself a westernizer, his rule was "[...] in the style of European absolutist monarchs, which in his view meant the encouragement of reform, particularly in the area of agrarian relations".[25] However, later, Tsars, particularly Nicholas I and Alexander III, intensified so-called Russification policies, imposing Russian as the official, administrative and educational language, undermining German and Latvian linguistic and cultural influence.[26] Although forceful conversion from Roman Catholics to „[…] Russian Orthodoxs could not be implemented“, the „church was deprived of many of its properties through a selective closing down of convents and monasteries“.[27] Catholic clergy could not be expelled, but their activities could be limited, such as restrictions on correspondence with Rome and travel outside their districts.

20th Century

[edit]World War I & Latvian Sovereignty

[edit]

During World War I, Latvia became a battleground between German and Russian forces, with the Baltic states becoming participants without choice. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and the collapse of the Russian Empire led to Latvia’s independence declaration on November 18, 1918, under non-Bolshevik Kārlis Ulmanis.[28] However, the newly formed government faced a Bolshevik invasion in December 1918, leading to a Soviet Latvian Republic under Pēteris Stučka. By early 1919, Ulmanis had fled to Liepāja, relying on German and Estonian forces. By mid-1919, the nationalist government regained control, defeating both Soviet- and German-aligned factions. In early 1920, the Red Army was expelled from Latgale with Polish assistance. A ceasefire was declared in February 1920, and on August 11, 1920, the Latvian-Soviet Treaty of Riga was signed, officially recognizing Latvia's sovereignty and securing its independence from Soviet influence.[29]

World War II & Soviet Reoccupation

[edit]

Latvia’s independence was short-lived; under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939), the Soviets occupied Latvia in 1940, incorporating it into the USSR as the „Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic“. This led to mass repression, including the deportation of over 15,000 Latvians to Siberia in June 1941.[30] Following Operation Barbarossa (1941), Nazi Germany occupied Latvia incorporating it into the Reichskommissariat Ostland. Latvians were forcibly conscripted into Nazi and Soviet armies. In 1943, the Germans formed the Latvian Legion, a Waffen-SS fighting on the Eastern Front, while others were drafted into the Red Army. As the Soviet Red Army launched its counteroffensive in 1944, the Soviets reoccupied Latvia, leading to further deportations and repression.[31] During the Holocaust in Latvia, between 1941 and 1944, more than 70,000 Jews were murdered.[32]

Aftermath & Independence Restoration

[edit]Latvia remained under Soviet control until 1991, but resistance persisted. National partisans, known as "Forest Brothers" ( Lv: mežabrāļi ), conducted a guerrilla war until the early 1950s, despite Soviet suppression.[33] The eventual collapse of the Soviet Union enabled Latvia to restore its independence on 21 August 1991, culminating a struggle that had lasted for nearly half a century.

Lithuania

[edit]

18th and 19th Century

[edit]Lithuania, the most southern country of the baltics, once was a powerful empire in the Middle Ages as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. From the 18th century onward, Lithuania gradually fell under Russian control. The third partition of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795 led to the annexation of most of Lithuania by the Russian Empire. The imperial authorities implemented a policy of Russification, as in Latvia, suppressing Lithuanian culture and language. [34] After the failed uprisings of 1831 and 1863, the Lithuanian nobility , closely linked to the Polish elite, faced severe repression for their resistance against Russian rule. In 1864, this resulted in the prohibition of the use of printing Lithuanian texts in the Latin alphabet, only Lithuanian texts in Cyrillic writing were allowed. Despite this repression, book smuggling (knygnešiai) played a key role in preserving the Lithuanian identity. Besides, schools were required to teach in the Russian language. As a consequence, Lithuanian teachers were dismissed and replaced with Russian ones. [35] This way of colonizing politics can be understood via the concepts of the author Homi K Bhabha who wrote Signs Taken for Wonders. Forbidding the Latin alphabet and mandating education in Russian, are expressions of Bhabha's signifier of authority and mirror his concept of the edict of Englishness, in this case, an edict of Russianness. These measures aimed to enfore cultural uniformity by marginalizing the Lithuanian language and identity. [36] Economically, Lithuania was being integrated into the Russian economy. Agricultural products and natural resources were exported to the Russian mainland, while Russians took key administrative positions, leaving Lithuanians with almost no say over their country. [37]

20th Century

[edit]Lithuania regained its independence in 1918 and lost it in 1940. [38] Lithuania experienced similar oppression by the Soviet Union as Latvia. Firstly, Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939), just like Latvia. The Red Army transformed the country into the "Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic", similar to the "Latvia Soviet Republic". During World War II, Lithuania was caught between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. After the annexation in 1940 by the Soviets, the Nazis took over in 1941. In 1944 the Soviets reoccupied the country. During the War and the Holocaust, many Lithuanian Jews were mudered.[39]

After the war, mass repression of the Lithuanian citizens followed under the rule of Joseph Stalin. Thousands of Lithuanians, including politicians , farmers and intellectuals were deported to the gulags in Siberia. [40] The government of the USSR also encouraged migration of Russian citizens to Lithuania, in an attempt to alter the demographic structure and solidify control. [41] After World War II, Lithuania underwent forced industrialization and argicultural collectivization. [42] The centrally planned economy in Moscow deprived Lithuania of its economic autonomy, and many Lithuanians saw Soviet policies as a form of economic exploitation. [43] Political dissent was surpressed, and Sovietization policies sought to subordinate Lithuanian traditions to Soviet ideology. [44]

Aftermath & Independence Restoration

[edit]Lithuania remained under Soviet control until 1990, but resistance was strong throughout the occupation. The "Forest Brothers" (Miško broliai) fought together in Lativa and Lithuania.

On 11 March 1990, Lithuania declared its sovereignty, officially restoring independence and marking the beginning of the end of Soviet rule in the region. This declaration set the stage for the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union and Lithuania’s full independence by 1991.[45] The experience of repression, deportations, and cultural erasure remains embedded in Lithuania's national memory. [46]

Post-1989

[edit]Societal Memory & Historical Narratives

[edit]The legacy of Russian colonization in the Baltic states has left a profound impact on historical narratives and collective memory. Throughout the Soviet period, official historiography promoted narratives that framed the Baltic states' incorporation into the USSR as a voluntary and beneficial process. However, this interpretation sharply contrasts with the perspectives in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, where Soviet rule is often regarded as an occupation, turning it into "an issue of perception"[47] or "a form of blindness" [48].

Following the fall and dissolution of the USSR in 1989 and its aftermath, the three nations undertook extensive efforts to reframe their historical narratives and emphasize national resistance and the loss of sovereignty. Memorials, museums, and the local educational system reflect this shift, highlighting Soviet-era deportations and human rights abuses.

The Museum of the Occupation of Latvia, the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights in Lithuania, and the Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom in Estonia exemplify these efforts to preserve and communicate this history. The controversial appeal of those monuments might stand out to most of its visitors as they are not preached or demolished. Monument to Petras Cvirka in Vilnius might represent a good example in this sense as the writer's well-known publishings represent a foundational part of the Lithuanian nation and culture contrary to the writer's public and private Soviet political beliefs[49]. Furthermore, similar examples of cultural milestones such as monuments or publications from the Sovietized past of the Baltics continue to impact the 'memory shift' [50] and their Baltic culture as it continues to affect the "history practices during and after the post-communist turn" [51]. In this sense, Estonian poets such as Hans Pöögelmann and August Alle expressed their communist or anti-communist beliefs through poetry.

Cultural & Linguistic Impact

[edit]Russian rule significantly influenced the cultural and linguistic landscape of the Baltic states. Under Soviet policies, Russian was established as the dominant language in administration, education, and media, often at the expense of native languages. Nils Muižniesk, a Latvian scholar and politician scientist, has named Russia's linguistic impact on the Baltics as an "asymmetric bilingualism"[52]. The forced Russification policies led to a decline in the use of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian in public life and the marginalization of national cultural expressions. Bilingualism was imposed in the educational systems as the Russian-speaking teachers would receive higher benefits than the teachers speaking the national language[53].

Since regaining independence after 1989, the Baltic states have implemented language policies to reduce Russian influence, as stated in articles 4 and 114 of the Latvian Constitution. Language laws were introduced to prioritize the use of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian in education, government, and public services. In Latvia and Estonia, this has included the gradual but tumultuous transition of Russian-language schools into national language programs, a policy that has been met with resistance from Russian-speaking communities in the Baltics after 1990[54]. These harsh measures taken during the transition period to democracy aimed at strengthening national identity but sparked debates over discrimination and minority rights from local Russian-speaking communities[55].

References

[edit]- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Sauer, Bernhard (1995). Die Baltikumer (in German). Institut für Internationale Politik und Regionalstudien.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ a b Kwai, Isabella (August 26, 2022). "Latvia tears down a controversial Soviet-era monument in its capital". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2025.

- ^ Tlostanova, Madina (2019). Albrecht, Monika (ed.). "The postcolonial condition, the decolonial option, and the post- socialist intervention". Postcolonialism Cross-Examined. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge: 165–178.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Tlostanova, Madina (2019). Albrecht, Monika (ed.). "The postcolonial condition, the decolonial option, and the post- socialist intervention". Postcolonialism Cross-Examined. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge: 165–178.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Annus, Epp (2011). "The Problem of Soviet Colonialism in the Baltics". Journal of Baltic Studies. 43 (1): 21–45.

- ^ Tlostanova, Madina (2019). Albrecht, Monika (ed.). "The postcolonial condition, the decolonial option, and the post- socialist intervention". Postcolonialism Cross-Examined. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge: 165–178.

- ^ Schmitz, Rob (August 19, 2022). "Latvia plans to destroy a Soviet-era monument, riling its ethnic Russian minority". NPR. Retrieved March 7, 2025.

- ^ Tlostanova, Madina (2019). Albrecht, Monika (ed.). "The postcolonial condition, the decolonial option, and the post- socialist intervention". Postcolonialism Cross-Examined. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge: 165–178.

- ^ Åselius, Gunnar. https://lib.uva.nl/permalink/31UKB_UAM1_INST/1hfh82p/cdi_unpaywall_primary_10_1080_23340460_2018_1528516.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Åselius, Gunnar. https://lib.uva.nl/permalink/31UKB_UAM1_INST/1hfh82p/cdi_unpaywall_primary_10_1080_23340460_2018_1528516.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sibul, Karin. https://lib.uva.nl/permalink/31UKB_UAM1_INST/1hfh82p/cdi_doaj_primary_oai_doaj_org_article_b14faf12745845c48e7fd7dabe96cb40.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Brüggenman, Karsten. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770608628880.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ peiker, Piret. https://lib.uva.nl/permalink/31UKB_UAM1_INST/1hfh82p/cdi_crossref_primary_10_1080_01629778_2015_1103516.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ monticelli, Daniele. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2014.899096.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Tulun, Mehmet Oğuzhan (25 February 2014). Russification Policies Imposed on the Baltic People by the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Başkent University.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Hiden, J. W. (1970). "The Baltic Germans and German Policy towards Latvia after 1918". The Historical Journal. 13 (2): 298. ISSN 0018-246X.

- ^ Sauer, Bernhard (1995). Die Baltikumer (in German). Institut für Internationale Politik und Regionalstudien.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 268. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Hiden, John (1991). The Baltic Nations and Europe. London and New York: Longman. pp. 107–126. ISBN 058225650X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "EHRI - Latvia". portal.ehri-project.eu. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ Hackmann, Jörg (1996). "The Baltic World and the Power of History". Anthropological Journal on European Cultures. 5 (2): 10. ISSN 0960-0604.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 235-236. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Bhabha, Homi K. 1985. “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817.” Critical Inquiry 12 (1): 144–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343466.

- ^ Cambridge University Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 294. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 347-358. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 377. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 366. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 363. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Plakans. A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 342-47. ISBN 9780511975370.

- ^ Senn, Alfred Erich. 1991. "Lithuania’s Path to Independence." *Journal of Baltic Studies* 22 (3): 245–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43211694.

- ^ Annus, Epp, Piret Peiker, and Liina Lukas. 2013. “Colonial Regimes in the Baltic States.” Interlitteraria 18 (2): 545. https://doi.org/10.12697/il.2013.18.2.19.

- ^ Račevskis, Kārlis (2002). "Toward a Postcolonial Perspective on the Baltic States". Journal of Baltic Studies. 33 (1): 37–56. ISSN 0162-9778.

- ^ Račevskis, Kārlis (2002). "Toward a Postcolonial Perspective on the Baltic States". Journal of Baltic Studies. 33 (1): 37–56. ISSN 0162-9778.

- ^ Davoliūtė, Violeta (2024-07-05). "Decolonisation in Lithuania?". kunsttexte.de - Journal für Kunst- und Bildgeschichte (in German): 1–12 Seiten. doi:10.48633/KSTTX.2024.1.102634.

- ^ Kõresaar, Ene; Jõesalu, Kirsti (2016). "Post-Soviet memories and 'memory shifts' in Estonia". Oral History. 44 (2): 47–58. ISSN 0143-0955.

- ^ Kõresaar, Ene; Jõesalu, Kirsti (2016). "Post-Soviet memories and 'memory shifts' in Estonia". Oral History. 44 (2): 47–58. ISSN 0143-0955.

- ^ Lazda, Mara (2009). "Reconsidering Nationalism: The Baltic Case of Latvia in 1989". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 22 (4): 517–536. ISSN 0891-4486.

- ^ Lazda, Mara (2009). "Reconsidering Nationalism: The Baltic Case of Latvia in 1989". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 22 (4): 517–536. ISSN 0891-4486.

- ^ Lazda, Mara (2009). "Reconsidering Nationalism: The Baltic Case of Latvia in 1989". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 22 (4): 517–536. ISSN 0891-4486.

- ^ Plakans, Andrejs (2014). A concise history of the Baltic States. Cambridge concise histories. Cambridge New York Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-97537-0.