Tigrayans

A Tigrayan man during the threshing of teff (Eragrostis tef) near Samre | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5.9 million (2024)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Tigrinya | |

| Religion | |

| Significant Majority: Tewahedo Orthodoxy (97,6%)[a] Catholicism (0,4%) Minority: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| • Habesha (Tigrinya, Amhara) • Tigre • Argobba • Beta Israel • Gurage • Harari • Zay • other[3][4]

a The word "Orthodoxy" here refers to Oriental Orthodoxy, not to be confused with Eastern Orthodoxy. All Habesha Orthodox Churches (EOTC, EriOTC and TOTC) are part of the Oriental Orthodox communion. | |

The Tigrayan people (Tigrinya: ተጋሩ, romanized: Təgaru) are a Semitic-speaking ethnic group indigenous to the Tigray Region of northern Ethiopia.[5][6][7] They speak the Tigrinya language, an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Ethiopian Semitic branch.

According to the 2007 national census, Tigrayans numbered approximately 4,483,000 individuals, making up 6.07% of Ethiopia’s total population at the time.[8] The majority of Tigrayans adhere to Oriental Orthodox Christianity, specifically the Tigrayan Orthodox Tewahedo Church, although minority communities also follow Islam or Catholicism.[9]

They speak Tigrinya, an Afroasiatic North Ethio-Semitic language descended from Geʽez, and written in the Geʽez script serves as the main and one of the five official languages of Ethiopia.[10] Tigrinya is also the main language of the Tigrinya people in central Eritrea, who share linguistic and religious ties with Ethiopian Tigrayans.[11]

Historically, the Tigrayan people are closely associated with the Aksumite Empire whose political and religious center was in Tigray,[12][13] and later the Ethiopian Empire.[14] Tigrayans played major roles in the political history of Ethiopia, including during the 17th-century Zemene Mesafint (Era of the Princes), and later in the 20th century through events the Woyane rebellion and the Ethiopian Student Movement, or movements like Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), which became the dominant faction in the coalition that overthrew the Derg in 1991 and ruled Ethiopia through the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) until 2018.[15][16]

Like other northern highland peoples, Tigrayans often identify with the broader Habesha (Abyssinian) identity—a term used historically to describe the Semitic-speaking Christian populations of the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands.[17][18]

Areas where Tigrayans have strong ancestral links are: Enderta, Agame, Tembien, Kilite Awlalo, Axum, Raya, Humera, Welkait, and Tsegede. The latter three areas are now under the de facto administration of the Amhara Region, having been forcibly annexed by Amhara during the Tigray War.

Origin

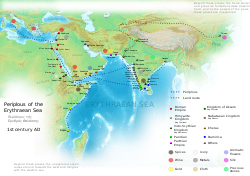

[edit]In his Geographia, the 2nd-century Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy, identifies a people known as the Tigritae or Tigraei (Τιγρῖται), located inland from the Red Sea coast in the area corresponding to the northern Horn of Africa. These names have been interpreted by some modern scholars as a possible early reference to the highlanders of modern-day Tigray and Eritrea.[19][20] Though the identification remains tentative, it is often regarded as the earliest known external allusion to a group or region bearing a name similar to Tigray.[19][20] On top of that, Ptolemy mentions the existence of a city called Coloe (Κολόη), which has been identified with Qohayto in Eritrea, placing his geographical framework close to the Tigray-Tigrinya highlands.[21][22][23][24]

The first clear references of Tigray emerged in 9th- to 12th-century Arabic geographical texts, where Islamic scholars such as Ibn Khurradādhbih, al-Yaʿqūbī, Ibn Ḥawqal, al-Maqdisī, al-Iṣṭakhrī, and al-Idrīsī refer to a region called Tīgrī or Tīgra, identifying it as a distinct Christian province within the broader kingdom of al-Ḥabasha (Abyssinia).[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32] These sources portray Tigray as a politically and culturally autonomous highland territory, often differentiated from neighboring regions such as Amhār (Amhara) and al-Bajā (Beja), and ruled by its own Christian authorities under the suzerainty of a king (the Negus).[33][34][35]

In his Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik ("The Book of Roads and Kingdoms"), the Persian geographer Ibn Khurradādhbih lists “Tīgrī” (تيغري) as a distinct Christian-inhabited territory under the rule of a king within the lands of al-Ḥabasha (Abyssinia), alongside other regions such as Nubia and al-Bajā (Beja).[25][36] His account marks the first known external textual identification of a distinct ethno-political region in what would later be formalized as Tigray.[25][36] A few decades later, al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897), in his Kitāb al-Buldān ("Book of Countries"), echoed this distinstiguishing Tigri from other regions such as Amhār and Kūstantīn (likely referencing the ancient Christian center of Aksum), this providing one of the earliest external sources to record a regional division resembling Ethiopia's later provinces.[26][37] Al-Iṣṭakhrī, in his own version of al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik, similarly names Tīgrī as one of the Christian territories of the Ethiopian highlands.[38] His contemporary, Ibn Ḥawqal, in his geographical treatise Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ ("The Face of the Earth"), likewise refers to Tīgrī (تيغري) as a distinct region within the broader Christian kingdom of al-Ḥabasha, emphasizing its separation from other regions such as the land of the Beja and Nubians.[27][39]

Shortly thereafter, al-Maqdisī (al-Muqaddasī), writing in his Aḥsan al-Taqāsīm fī Maʿrifat al-Aqālīm ("The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions"), includes Tīgrī in his description of the “land of the blacks” (bilād al-sūdān), specifically noting it as one of several Christian realms inland from the Red Sea. Later, al-Idrīsī, writing in Norman Sicily in 1154 CE, describes “Tīgra” as a province of the kingdom of al-Ḥabasha in his major work Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq. These texts collectively suggest that the toponym "Tigray" (or its variants Tīgrī, Tīgra) had entered the lexicon of Islamicate cartography and ethnography by the early medieval period.[40][41][42][43]

While early Islamic geographers offered some of the first external references to Tigray, it should also be acknowledged that the Christian world, particularly through late antique and medieval sources, retained knowledge of the region primarily through ecclesiastical and geographic lenses. A notable example of that appears in a marginal 10th-century gloss to the works of Cosmas Indicopleustes, a 6th-century Alexandrian merchant and Christian monk who had traveled to the Red Sea. According to this source, the inhabitants of the northern Ethiopian highlands are referred to as the Tigrētai (Greek: Τιγρήται) and the Agazē (Greek: ἀγαζη), the latter term referring to the "Agʿazi" (Ge'ez: አግዓዚ) people, who were associated with the Aksumite ruling elite and Semitic-speaking highlanders.[44]

By the 14th century, the term Tigray appears in Geʽez royal chronicles and administrative records during the reign of Emperor Amda Seyon (1314–1344), referring to a northern province of the Ethiopian Empire governed by regional nobles and military leaders.[45][46]

The earliest known European references to the region of Tigray appear in the 16th century, during the period of Portuguese exploration and diplomatic engagement with the Christian Ethiopian Empire. One of the most important early witnesses was Francisco Álvares, a Portuguese priest and royal envoy who accompanied the 1520–1527 mission to the court of Emperor Lebna Dengel. In his account, Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João das Indias ("A True Relation of the Lands of Prester John of the Indies"), Álvares explicitly names “Tigré” as a major province of the empire. He describes it as a land of stone churches, learned clergy, and ancient Christian traditions, particularly focusing on Aksum, which he identified as the site of royal coronations and religious reverence. Álvares also records the presence of the local nobility and refers to Tigré's role in resisting the Muslim incursions led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi during the early stages of the Ethiopian–Adal war.[47][48]

Following Álvares, the Jesuit missionary Jerónimo Lobo, who traveled through Ethiopia in the early 17th century, also emphasized the importance of Tigré as a Christian stronghold. In his travel narrative Itinerário e outras obras, he recounted the region's churches, monastic communities, and its connections to early Christian relics and traditions, including associations with the Ark of the Covenant in Aksum. He identified Tigré as distinct from other provinces such as Amhara or Shewa, and praised the piety and hospitality of its people. His writings were later translated and popularized in English by Samuel Johnson, further spreading knowledge of Tigré among European readers.[49][50]

In the later 17th century, the most comprehensive European treatment of Ethiopian geography and culture was produced by Hiob Ludolf, a German orientalist and linguist whose Historia Aethiopica (1681) became the standard European reference on Ethiopia for decades. Ludolf based his work on Ethiopian sources, interviews with Ethiopian monks and emissaries in Rome, and correspondence with Jesuit missionaries in the Horn of Africa. He refers to Tigray as “Regio Tigrensis” or “Tigraia”, describing it as one of the core regions of the Empire. Ludolf notes its proximity to the Red Sea, its connection to the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, and its linguistic particularities — identifying Tigrinya as a variant of Geʿez still spoken by the people of the region. He includes maps and ethnographic details that distinguish Tigray from neighboring regions such as Amhara and Begemder.[51][52]

These early European sources consistently depicted Tigray not only as a geographically distinct province but also as a religious and historical heartland of the Ethiopian state. They frequently associated it with the memory of Aksumite kingship, monastic scholarship, and the ecclesiastical authority of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[53][54][55] Over time, references to "Tigré" and "Tigrai" became standard in European maps and writings on the region, including those by cartographers such as Ortelius, Blaeu, and d’Anville, who often marked “Tigre Regio” or “Regnum Tigré” on maps of East Africa produced between the 16th and 18th centuries.[56][57][58]

The Scottish explorer James Bruce, writing in the late 18th century, described Abyssinia as geographically divided into two principal provinces: “Tigré, which extends from the Red Sea to the river Tacazzé; and Amhara, from that river westward to the Galla, which inclose Abyssinia proper on all sides except the north-west.” Moreover, he emphasized the commercial importance of Tigray due to its proximity to the Red Sea trade routes:

"Tigré is a large and important province, of great wealth and power. All the merchandise destined to cross the Red Sea to Arabia must pass through this province, so that the governor has the choice of all commodities wherewith to make his market."[59]

By the early 19th century, English diplomat and Egyptologist Henry Salt also emphasized the strategic and military strength of Tigray. In his 1816 account A Voyage to Abyssinia, Salt identified three great divisions of the Ethiopian highlands: Tigré, Amhara, and Shewa.[60][61] He considered Tigré to be the most powerful of the three, citing “the natural strength of the country, the warlike disposition of its inhabitants, and its vicinity to the sea coast,” which enabled it to secure a monopoly on imported muskets.[62]

Salt further subdivided the kingdom of Tigré into smaller provinces, referring to the heartland as Tigré proper. This included districts such as Enderta, Agame, Wojjerat, Tembien, Shiré and Baharanegash.[63] Within Baharanegash, the northernmost district of Hamasien marked the edge of Tigré, beyond which Salt noted the presence of the Beja (or Boja) people living further north.[62][64][65]

Ethnogenesis

[edit]Tigrinya is a North Ethio-Semitic language, closely related to Geʽez and spoken primarily by the Tigrayans and the Tigrinya people of central Eritrea.[66][67] The ethnogenesis of the Tigrayan people is rooted in the interaction between Semitic-speaking Aksumites, who spoke early forms of Geʽez, and the Cushitic-speaking populations inhabiting the northern Horn of Africa, such as the Agaw.[68][69] During the height of the Kingdom of Aksum (c. 1st–7th century AD), the political, religious, and linguistic center of the empire was located in modern-day Tigray and Eritrea, with cities like Aksum and Adulis serving as hubs of trade, Christianity, and imperial administration.[70][71]

Building on this historical foundation, scholars have identified the term Agʿazi (Geʽez: አግዓዚ) in early inscriptions and royal texts from the pre-Aksumite and Aksumite periods, as referring to both a Semitic-speaking people and their language, widely seen as ancestral to the Tigrinya-speaking populations of the northern highlands. Modern scholars regard the Agʿazi as the direct ethnolinguistic ancestors of the Tigrayan and Tigrinya populations of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, rather than of the Amhara, whose language and sociopolitical structures evolved farther south under different influences.[72][73] The development of Geʽez into Tigrinya and Tigre is thus seen as a process of regional linguistic continuity, whereas Amharic—while part of the broader Ethio-Semitic family—emerged in a later context, shaped by Cushitic substrata and more distant from the core Agʿazi heritage.[74][75]

As the Aksumite polity declined and political power shifted southward, many northern highland communities continued to speak local derivatives of Geʽez, giving rise to Tigrinya as a distinct vernacular language by the early second millennium.[76][77] The gradual consolidation of Tigrinya-speaking communities, coupled with common religious affiliation to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and localized political traditions (such as the rules of Bahr negash and Tigray Mekonnen in northern Tigray and Eritrea), fostered the emergence of a coherent Tigrayan identity.[78][79] Archaeological, linguistic, and historical evidence suggest that the Tigrayan ethnolinguistic group thus emerged through a long process of ethno-cultural continuity and differentiation within the broader Aksumite and post-Aksumite highland society.[80][81]

Moreover, the British explorer Charles Tilstone Beke, who traveled in Ethiopia in the 1840s, asserted that the Tigréans and Amharas were “two different races, differing in language, character, and physiognomy”, and argued that the Tigréans were the “true representatives of the ancient Abyssinians” due to their continuity with the Aksumite heritage.[82] His conclusions reflected a broader trend among 19th-century European travelers—such as James Bruce, Henry Salt, and later Theophilus Waldmeier—who associated the Tigrayan people with the historical legacy of the Aksumite Empire, and by extension, the classical Christian civilization of Ethiopia.[83][84][85] This association was often based on the concentration of early Christian monuments in Tigray (particularly in Aksum, Yeha, and Adwa), the continued use of Tigrinya, a language derived from Geʽez, and the presence of monastic traditions viewed as direct descendants of early Ethiopian Orthodoxy.

Later scholars, such as Edward Ullendorff, would argue that the linguistic and religious conservatism of the northern highlands (especially the retention of Geʽez in church liturgy and the preservation of Aksumite ruins) contributed to a historical self-perception among Tigrayans as guardians of ancient Ethiopian identity, in contrast to the Amhara, who came to political prominence in later medieval and early modern periods.[86]

Etymology

[edit]The toponym Tigray is probably originally ethnic, the Tigrētai then meant "the tribes near Adulis." These are believed to be the ancient people from whom the present-day Tigrayans, the Eritrean tribes Tigre and Tigrinya are descended from.[44]

Although the linguistic roots of the name Tigray are not definitively established, several theories exist. Some scholars link it to the Geʽez root "ተገረ" (Tagära), meaning “to ascend” or “upper place,” possibly referring to the elevated terrain of the Tigrayan plateau.[87] A common theory holds that Tigray is a later evolution of the root “T’GR”, which may have originally referred to a specific sub-region or population within the Aksumite kingdom.[88] In this reading, the word may have designated the central-northern highland area from which the language now known as Tigrinya later emerged.[89]

Another strand of scholarship focuses on the ethnonym Təgaru (ተጋሩ) — the endonym used in Tigrinya to refer to the Tigrayan people — and its relation to the language name Tigrinya (ትግርኛ, Tǝgrǝñña). Some linguists argue that the root TGR is not only geographic (as in Tigray) but also ethno-linguistic, originally designating speakers of a Geʽez-derived northern Semitic language who maintained cultural and political continuity from the Aksumite period.[90] The suffix (Ge'ez: ኛ, romanized: inya) as in Tigrinya: ትግርኛ, romanized: Təgrəñña is a typical Geʽez-derived marker for languages or affiliations (comparable to Amharic: አማርኛ, romanized: Amarəñña from Amhara), making Tigrinya literally mean "of the Tigray" or "Təgaru-related".[91]

While some late sources have occasionally associated Təgaru with wider Semitic groups, most academic interpretations consistently link it to the inhabitants of the central-northern highlands, particularly those whose liturgical and linguistic practices descend from Geʽez.[92][73] This framing further reinforces the distinction between Tigrinya as an indigenous highland language and the later emergence of Amharic to the south.[91]

Some marginal interpretations, often found in 20th-century colonial-era dictionaries or speculative linguistic notes, attempt to impose a rigid social hierarchy between the Agʿazi (or "Gäzé") and the Tigretês, framing the former as “nobles” and the latter as socially subordinate or ethnically mixed. However, this interpretation has been challenged by scholars who argue that the derivation of Təgaru from the Geʽez root gäzärä (ገዘረ, “to subdue”) is speculative and lacks support from primary Aksumite inscriptions or early literary sources.[73][90] Rather than being socially subordinate or external to the Aksumite elite, the forefathers of the Tigrinya-speaking communities were integral to the Aksumite Empire, especially in the preservation and transmission of Geʽez, Orthodox Christianity, and classical architecture. Their historical centrality is evidenced by their custodianship of core highland religious and cultural centers such as Aksum, Yeha, and Debre Damo.[93][94][95] Moreover, linguistic studies affirm that terms like Təgaru and Tigrinya derive from indigenous Ethio-Semitic roots linked to the highland region—not from imposed designations of subjugation.[91][74] As such, framing the Tigrétês as a socially inferior group distinct from the Agʿazi overlooks the ethno-linguistic continuity and cultural authority of the northern highland populations, who were among the primary successors of the Aksumite Empire.[96][97][98][99]

In modern usage, "Tigray" refers to both the region and the ethnic group primarily residing in Ethiopia’s northern highlands, while "Tigrayan" (Tigrinya: ተጋሩ, romanized: Təgaru) designates the people, language, and shared cultural identity associated with that region.[100][73][101][102] The term remains distinct from but historically related to Tigre, which refers to a different ethnic group speaking the Tigre language in Eritrea.[103][104]

History

[edit]The Tigrayan people's long and rich history is undoubtedly intertwined with the formation of the Ethiopian state, its religious traditions, and the development of its distinct cultural identity. Due to its pivotal role in early Ethiopian history, particularly as the heartland of its ancient Semitic civilizations like D'mt or the Kingdom of Aksum, Tigray is sometimes designated as the "cradle of Ethiopian civilization."[105]

According to Edward Ullendorff, the Tigrinya speakers in Eritrea and Tigray are the authentic carriers of the historical and cultural tradition of ancient Abyssinia.[106] For their part, Donald N. Levine and Haggai Erlich regard the contemporary Tigrayans to be the successors of the Aksumite Empire.[107]

Kingdom of D'mt

[edit]

The Tigrayans trace their origin to early Semitic-speaking peoples whose presence in the region may date back to at least 2000 BC.[108] One of the first known civilizations to emerge in the area was the Kingdom of D'mt, which flourished around the 10th century BCE. The capital of this ancient kingdom may have been near modern-day Yeha, where the remains of a large temple complex and fertile surroundings suggest a well-established and advanced society.[109] Indeed, D'mt was known for its advanced agricultural practices, including the use of ploughs and irrigation systems, as well as its production of iron tools and weapons. Archaeological evidence suggests that D'mt was an important center of trade, interacting with surrounding regions, especially Arabia and the broader Red Sea world.[110]

However, the origins of D'mt have been a subject of scholarly debate. Some historians, such as Stuart Munro-Hay, Rodolfo Fattovich, Ayele Bekerie, Cain Felder, and Ephraim Isaac, view the civilization as primarily indigenous, though influenced by Sabaean culture due to the Sabaeans' dominance over the Red Sea trade routes.[111][112] Others, including Joseph Michels, Henri de Contenson, Tekletsadik Mekuria, and Stanley Burstein, suggest that D'mt emerged from a blend of Sabaean and indigenous peoples, reflecting a synthesis of Arabian and local African cultural influences.[113][114]

Aksumite Empire

[edit]

By the 1st century CE, D'mt had been supplanted by the rise to prominence of the Aksumite Empire in the region. Centered around Tigray and Eritrea, it quickly established itself as one of the most powerful civilizations of antiquity alongside Rome, Persia, and China by controlling much of the Red Sea coast, parts of the Arabian Peninsula, and modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Moreover, its strategic position also made it a powerful player in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade networks with the exportation of luxury goods such as ivory, gold, frankincense, and myrrh and the importation of silk, wine, and other exotic goods, which allowed it to prosper and expand its influence far beyond the Horn of Africa.[115][116][117][118]

On top of that, the empire was also renowned for its technological and architectural feats, which highlighted both its advanced engineering and cultural significance.

The Aksumites erected monumental stelae and obelisks such as the Ezana Stone or the Obelisk of Axum, which were used either as grave markers for Aksumite royalty or as testaments to both their political and religious power while remaining to this day one of the most iconic symbols of the empire's grandeur.[119] Their advanced water management systems, including dams and irrigation channels, enabled the empire to sustain agricultural productivity and support its growing population, further solidifying its economic base.[120]

Aksumite legacy on Tigrayan cultural identity

[edit]

In addition to its architectural marvels, Aksum's cultural and religious importance on the Tigrayan people was profound. As Christianity arrived in the region during the 4th century CE, the subsequent conversion of King Ezana, making Aksum one of the earliest empires to adopt Christianity as the state religion, represented a crucial turning point in the religious and cultural development of the Tigrayan people by embedding Christianity deeply as one of its distinguishing features.[120][121] Over the following centuries, the region not only preserved the newly adopted faith but also helped developing it into the uniquely Ethiopian form of Christianity that would endure throughout the latter's tumultuous history.[122][123]

Aksum's shift towards Christianity led to the establishment of churches, monasteries, and religious institutions throughout Tigray and Eritrea, many of which became centers of learning, intellectual exchange, theological development, thereby nourishing the emergence of the Ge'ez script, used for religious texts and which evolved into the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[120][124] While being the birthplace of Tewahedo Orthodoxy, Aksum also became Ethiopia's holiest site — a "New Jerusalem"[a] - due to the popular belief that the Ark of the Covenant resides at the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion.

This connection to biblical history, coupled with the region's thriving monastic and religious culture, bestowed upon the city of Aksum—and by extension, the Tigrayan people—a distinct spiritual status. Therefore, this heritage positioned them not only as custodians of Ethiopia's ancient Christian tradition but also as the guardians of the Christian faith in Africa.[125][123][126]

Building upon this spiritual foundation, Aksum's symbolic weight extended beyond religious prestige; it became a cornerstone of imperial legitimacy and national identity. Successive Ethiopian emperors deliberately sought to anchor their authority in the city's sacred legacy, with coronation ceremonies in Aksum becoming an indispensable rite of passage.[127][128]

This tradition firmly wove the Tigrayan highlands into Ethiopian Empire’s political and spiritual fabric, ensuring that the memory of Aksum remained inseparable from the ideals of kingship, unity, and divine favor that would define the Ethiopian state for centuries.[126][123]

For all these reasons, proeminent historians such as Edward Ullendorff, Donald N. Levine and Haggai Erlich regard the contemporary Tigrayans (and Tigrinyas in Eritrea) as the successors of the Aksumite Empire and the authentic carriers of the historical and cultural tradition of ancient Abyssinia.[106][107]

Zagwe dynasty (1137-1270)

[edit]

During the Zagwe dynasty, Tigray played a significant role in both the political and religious development of the Ethiopian highlands. While Zagwe kings themselves came were not from Tigray but from the Lästä region, they nonetheless claimed descent from Aksumite nobility despite their Agäw origins and remained closely connected to the northern highlands, particularly through monastic institutions and ecclesiastical networks centered in Tigray.[129][130] Important religious centers such as Debre Damo, Debre Maryam Qorqor, and Debre Abbay in Tigray remained active throughout the Zagwe period, serving as centers of theological learning, manuscript production, and regional authority.

While the Zagwe court attempted to establish legitimacy through monumental church-building projects in Lästä (such as the famous rock-hewn churches of Lalibela), they also relied on the prestige of Aksumite ancestry, which remained rooted in Tigray's cultural memory. Several traditions, preserved in later Ethiopian chronicles and hagiographies, suggest that the clergy and monastic elite in Tigray acted as both legitimizers and critics of the Zagwe monarchs, often urging a return to the Solomonic line associated with Aksum.[71][131]

This ethnic and cultural connection to Tigray allowed the Zagwe rulers to establish a powerful religious and political network that thrived in the northern highlands. Tigrayan nobles provided military and administrative support to the Zagwe kings, and their loyalty ensured the persistence of the dynasty, despite challenges from external and internal forces.[132][133] For instance, King Lalibela married a woman from the Tigrayan aristocracy to strengthen the dynasty's rule over the region.[134]

Solomonid Dynasty (1270-1974)

[edit]Early Solomonic Period (1270-1632)

[edit]Early Modern Period (1632–1855)

[edit]Modern Period (1855-1974)

[edit]Contemporary Era (1974-present)

[edit]The Ethiopian Revolution and the rise of the TPLF (1974-1991)

[edit]The EPRDF in power (1991-2018)

[edit]The Tigray War and its aftermath (2020-present)

[edit]Demographics

[edit]

The 2007 Ethiopian census recorded 4,483,741 Tigrayans in Ethiopia, making up 6.1% of the national population and constituting the fourth largest ethnic group in the country after the Oromo, Amhara and Somali.[135][136] However, independent estimates placed the population closer to 5.5–6.3 million by 2020, just before the outbreak of the Tigray War.[137][138][139]

As of 2023, ethnic Tigrayans are estimated to range between 4.0 and 4.5 million inside Ethiopia, with a global estimate ranging from 5.7 to 7.3 million when diaspora populations are included, though precise figures are difficult to ascertain due to recent war-related demographic shocks, forced displacement, and restricted access to accurate census data.[140][141][142] The predominantly Tigrayan-populated urban centers are found in towns including Mekelle, Adwa, Axum, Adigrat, and Shire. Huge populations of Tigrayans are also found in other large Ethiopian cities such as the capital Addis Ababa and Gondar.

Accurate population data is difficult to obtain due to the effects of the Tigray War (2020–2022), which caused widespread destruction of civil registries, mass displacement, and restrictions on humanitarian access. Independent estimates suggest that between 385,000 and 600,000 Tigrayans may have died from direct violence, famine, and lack of medical care during the conflict.[143][144][145] Over 60,000 people fled to Sudan, and hundreds of thousands were internally displaced.[146] Human rights organizations have described these events as ethnic cleansing and genocide, particularly in Western Tigray, where Amhara regional forces forcibly expelled Tigrayan civilians and erased local administrations.[147][148]

In the 19th century, foreign observers such as James Bruce and Henry Salt described Tigray as one of the most populous and politically dominant regions in the Ethiopian Highlands.[149][150] At the time, Tigray was a center of imperial politics, literacy, and trade, often rivaling Shewa in military and cultural influence. However, its share of the national population gradually declined over the subsequent two centuries due to a combination of environmental, political, and economic factors.

The decline of Tigrayan population can be traced back to the Kifu Qen (Amharic: ክፉ ቀን, lit. “evil days”), the great famine of 1888–1892. Triggered by drought, locust invasions, and a devastating rinderpest outbreak, the famine severely affected the Ethiopian highlands, particularly in Tigray, wiping out over 90% of Ethiopia's cattle, the collapse of entire communities, and causing the deaths and displacements of hundreds of thousands of people.[151][152][153][154][152] The effects of this “evil time”—including mass mortality, displacement, and social disintegration—left long-term demographic scars and are often cited as the beginning of Tigray's descent from a dominant regional power to a peripheralized province.[155][156][157] Another major demographic crisis occurred during the 1958 famine in Tigray, which reportedly killed over 100,000 people.[158][159][160][161] This was followed by a more devastating episode during the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, which disproportionately affected Tigray, Wollo, and Eritrea.[162][163] The Derg military regime under Mengistu Haile Mariam used the famine as a counter-insurgency strategy against the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), deliberately withholding food aid from rebel-held and civilian areas in what scholars and aid workers described as a politicized famine.[164][165][166] According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the famine killed more than 300,000 people, and some estimates place the toll as high as 1.2 million.[167][168]

In the 1990s, the creation of Ethiopia's ethnic federal system led to the incorporation of Welkait, Tsegede, and Tselemti—formerly part of the historical Begemder province—into the newly formed Tigray Region.[169][170] This move was justified by the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) based on local identity and self-determination, but was contested by Amhara political forces. During the Tigray War, these districts were retaken by Amhara forces, who conducted mass expulsions of Tigrayan residents and took control of local administrations.[171][147]

As a result of decades of instability, war, and repression, many Tigrayans have emigrated. The Tigrayan diaspora in the United States alone is estimated to include over 35,000 first-generation migrants, with tens of thousands more in second-generation or undocumented populations.[172][173] Large diaspora populations are also found in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Nordic countries, Sudan, and the Gulf States.[174][175]

Subregions

[edit]Although the Tigrayans constitute a single ethnolinguistic people, internally they have long exhibited regional and historical sub-identities with their own socio-cultural traditions that correspond to specific highland districts, dialect zones, and former local principalities.[176][177]

Historically, Tigray was divided into semi-autonomous districts ruled by hereditary elites bearing titles such as Shum Agame, Shum Tembien, and Shum Enderta.[178] These principalities—like Enderta, Tembien, and Agame—served as religious and political centers tied to the broader imperial structure. Agame, for example, bordered modern Eritrea and often supplied high-ranking clergy and officials.[179] While autonomous in certain eras, they were interconnected through marriage alliances, military coalitions, and a common allegiance to the Christian highland polity centered in Aksum and later in Adwa and Mekelle.[180][181]

The central and eastern highlands—including Enderta, Tembien, and Agame—formed the historic core of Tigray and were home to major monasteries, Christian institutions, and leaders like Ras Mikael Sehul, Ras Wolde Selassie, Shum Agame Sabagadis Woldu and Ras Alula Engida.[182] The southern districts, notably Raya and Ofla, lie at a cultural crossroads with the Amhara and Afar peoples but remain firmly rooted in Tigrayan identity through language, kinship, and religious affiliation.[183] To the west, areas such as Welkait, Humera, and Tsegede were long inhabited by Tigrinya-speaking Tigrayans and historically administered as part of Tigray, though they became zones of violent displacement and identity-based repression during the Tigray War (2020–2022).[184]

Language

[edit]

Tigrinya (ትግርኛ) is a North Ethio-Semitic language spoken by an estimated 7 to 9 million people across the Horn of Africa, making it one of the most widely spoken Ethio-Semitic languages after Amharic.[185][186]

In Ethiopia, Tigrinya is the principal language of the Tigray Region, spoken by approximately 4.5 to 5 million people, or around 4–5% of the national population.[187] In Eritrea, it is spoken by roughly 2.5 to 3 million people, constituting about 50–55% of the population and serving as the country's de facto national language, used in administration, media, and education alongside Arabic.[188][189] Though mutually intelligible, both varieties have developed under different political and educational systems, leading to subtle differences in orthography, terminology, and media standardization.[190]

Tigrinya traces its roots in the ancient Geʽez-speaking Kingdom of Aksum. As Geʽez ceased to be spoken as a vernacular by around the 10th century CE, descendant languages began to emerge in the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands. Tigrinya is believed to have developed as a distinct spoken language during the early medieval period, evolving primarily in the highlands of Tigray and Eritrea. The earliest known written attestation of Tigrinya is found in a 13th-century land grant inscription discovered in the Monastery of Däbrä Maryam Qorqor in eastern Tigray, contains grammatical features and vocabulary that diverge from classical Geʽez and are widely recognized as early Tigrinya.[191][192][193]

The linguistic continuity between Geʽez and Tigrinya was reinforced by the use of Geʽez in church liturgy and scriptural translation, while Tigrinya remained a spoken vernacular used in day-to-day life. Over centuries, the consolidation of Tigrinya-speaking communities in provinces such as Enderta, Agame, and Tembien contributed to the shaping of a shared ethnolinguistic identity among Tigrayans, distinct from their northern Tigre-speaking and southern Amharic-speaking neighbors.[68][78]

Several Tigrinya dialects, which differ phonetically, lexically, and grammatically from place to place, are more broadly classified as Eritrean Tigrinya or Tigray (Ethiopian) dialects.[194] No dialect appears to be accepted as a standard. Tigrinya is closely related to Amharic and Tigre (in Eritrea commonly called Tigrayit), another East African Semitic language spoken by the Tigre as well as many Beja of Eritrea and Sudan. Tigrinya and Tigre, though more closely related to each other linguistically than either is to Amharic, are however not mutually intelligible. Tigrinya has traditionally been written using the same Ge'ez alphabet (fidel) as Amharic and Tigre.

Religion

[edit]Aksumite polytheism

[edit]Before the adoption of Christianity in the 4th century CE, the ancestors of the Tigrayan people practiced a polytheistic religion that incorporated both indigenous African beliefs and external influences from South Arabia. Several deities were worshipped, including Almaqah, the moon god also revered by the Sabaeans, as well as other Semitic gods such as the sun god Utu, ʾĪlā and Wadd.[195][196] These practices were especially prominent during the pre-Aksumite and early Aksumite periods, which had strong Red Sea trade links with ancient Yemen.

Archaeological remains such as the Temple of Yeha in Tigray, dated to the 7th century BCE, show clear South Arabian architectural influence and are believed to have served as temples dedicated to Almaqah.[197] Other sites across the region feature shaft tombs, stelae, and altars used in pre-Christian ritual activity. The use of the Musnad script and references to Arabian deities in local inscriptions point to a period of religious syncretism before the Christianization of the region under Emperor Ezana.[198][199]

Christianity

[edit]Oriental Orthodoxy

[edit]Christianity has been the predominant religion of Tigrayans since antiquity. The vast majority of Tigrayans are adherents of Tewahedo Oriental Orthodoxy, specifically the Tigrayan Orthodox Tewahedo Church which has historically been the dominant religious institution in the region.[78][200] In fact, Tigray is often regarded as the spiritual heartland of Ethiopian Orthodoxy, due to its association with the early Christian Kingdom of Aksum. According to tradition and early inscriptions, Christianity was introduced to Aksum in the 4th century CE by St. Frumentius (Ge'ez: አባ ሰላማ ከሳተ ብርሃን, romanized: ʾAbā Sälāmā Käsātä Bərhān),[b] who was consecrated as the first Bishop of Ethiopia by St. Athanasius, the Patriarch of Alexandria.[71][68]

Another pivotal moment for Tigrayan Christianity is the arrival of the Nine Saints (Ge'ez: ቱዐታት ቅዱሳን, romanized: Tuʾātāt Qeddusān)[c] during the late 5th to early 6th century CE. These ascetic monks, traditionally said to have come from the Byzantine Syria, are credited with reviving Christian monasticism in the Aksumite realm following the conversion of King Ezana. Settling in different parts of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, particularly in Tigray, they established monasteries, schools, and churches, translated biblical and patristic texts into Geʽez, and promoted Miaphysite doctrine and monastic discipline.[201][202]

Among the most prominent foundations associated with the Nine Saints are the monasteries of Debre Damo (founded by Abuna Aregawi), Abuna Yemata Guh, Abba Pantalewon, Mata Mekel, Mesḥa, and May Qoybah which became hubs of theological learning and spiritual authority, and played a key role in shaping Ethiopian monastic architecture, hymnography, and liturgy. The saints are also credited with standardizing the use of the Geʽez language for liturgical purposes and transmitting elements of Syriac and Coptic Christian thought into the Ethiopian context.[203][204] The legacy of the Nine Saints adds to Tigray’s reputation as a cradle of Ethiopian Orthodox monasticism and theological development.[205][206]

Tigray is also home to some of the oldest and most significant churches such as the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, Abreha we Atsbeha, Teka Tesfay, but also numerous rock-hewn churches, many of which are believed to predate the more famous monolithic churches of Lalibela. Numbering over 120, they contain mural iconography that reflects a synthesis of Byzantine, Coptic, and local Ethiopian styles, depicting biblical scenes, saints, and angels with distinct Tigrayan features and attire.[207]

In addition, the region has long been a center of religious art and manuscript production within the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition. The region's churches and monasteries are renowned for their wall paintings, carved icons, illuminated manuscripts, and rock-hewn architecture,[208][209] while contributing significantly to the transmission and preservation of Ge'ez religious texts, producing manuscripts in local scriptoriums that combined calligraphy, theological commentary, hymnography (zema), and illustrated miniatures.[80][210][211][212] Several Tigrayan monasteries served as centers of Orthodox clerical education and liturgical training and oral transmission of Ge'ez chants, prayers, and exegetical tradition.[213]

This long-standing manuscript and monastic tradition in Tigray is closely intertwined with the development of the region's unique liturgy and sacred chant. The origins of this rich liturgical and musical heritage are traditionally attributed to Saint Yared, a Tigrayan-born composer and scholar who is credited with developing the Zema, a system of sacred music composed in Ge'ez, which still serves as foundation of all Tewahedo, Ethiopian Catholic and Eritrean Catholic liturgical practice.

His compositions are preserved in major chant books such as the Deggua, which contains hymns for feast days and daily services, the Zema Zēta, used for antiphonal chants, and the Mewas'et, which includes funeral music. Taught and transmitted through oral tradition in monastic liturgical schools, Yared's system remains integral to the identity of Ge'ez rite worship and is particularly revered in the churches and monasteries of Tigray, where his legacy is most closely tied.[214][215][216]

Throughout medieval and early modern Ethiopian history, Tigrayan clergy and monastic communities were highly influential in shaping theological debates, religious practices, and church-state relations. Monastic movements such as those founded by Ewostatewos and Abba Estifanos of Gwendagwende originated in Tigray and advocated for liturgical purity, Sabbath observance, and a stricter interpretation of Orthodox tradition. The followers of Ewostatewos (Ewostathians) played a major role in defending indigenous religious practices against foreign and royal interventions, eventually influencing national doctrine.[78][217]

The ecclesiastical office of the Bahre Negeśt, often based in the coastal and highland regions of Tigray, was historically responsible for administering large Orthodox dioceses and coordinating religious authority between the center and the periphery.[218]

Prominent Ethiopian Orthodox saints and writers, including Abba Yohanni of Däbrä Qwästos, Abba Libanos and Abba Samuel of Waldebba, are also traditionally associated with the region. These figures contributed to the development of mystical theology, fasting practices, and monastic discipline within the Orthodox tradition.[219][220] Many of their monasteries remain active pilgrimage sites today, particularly during feast days and local fasts.

In modern times, the Orthodox Church continues to play a central role in the religious and cultural identity of Tigrayans, with most rural communities organized around local parishes, feast-day observances, and monastic networks.

Catholicism

[edit]Catholicism among the Tigrayan people has historical roots in the Jesuit missions of the 16th and 17th centuries. During this period, Portuguese-supported missionaries such as Francisco Álvares, Pedro Páez and Manuel de Almeida established religious centers in the northern highlands, notably at Fremona, near Adwa, which served as the Jesuit headquarters in Ethiopia. While the mission ultimately failed due to local resistance and the imperial expulsion of the Jesuits in 1632, it introduced Roman Catholic theological concepts and liturgical influences that would later be revived.[221][222]

The modern Catholic presence in Tigray Region is mainly associated with the Ethiopian Catholic Church, a sui iuris church of the Eastern Catholic Churches that follows the Alexandrian Rite, similar in structure to the Orthodox Tewahedo Churches but in full communion with the papacy. Catholicism was reintroduced in the 19th century through the efforts of Lazarists and Capuchin missionaries, supported by the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide). Their activities focused on education, translation, health, and liturgical accommodation to local customs.[223][224] These missions laid the foundations for the establishment of the Eparchy of Adigrat in 1939, which today is as the main ecclesiastical seat for Catholics in northern Ethiopia.[225][226]

As of the early 21st century, the Eparchy of Adigrat serves tens of thousands of Tigrayan Catholics, and includes parishes, schools, and religious orders operating in the region.[227][226] The liturgy is conducted in Geʽez, and priests are typically drawn from local Tigrayan communities.

Most Catholics in Tigray belong to the Irob people, an ethnic subgroup inhabiting the northeastern escarpments of the Tigray Region near the Eritrea–Ethiopia border. The Irob have historically maintained a distinct religious identity, preserving Catholic faith practices while participating in broader Tigrayan linguistic and cultural life.[228][229]

While Catholics remain a minority among Tigrayan Christians—who are overwhelmingly adherents of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church—they continue to play a significant role in religious, educational, and social life, particularly through schools, health centers, and monastic communities affiliated with the Eparchy of Adigrat.

Islam

[edit]While the majority of Tigrayans adhere to Christianity, a historically rooted minority of Muslims has long existed in the Tigray Region. The presence of Islam is traditionally linked to the First Hijrah in the 7th century CE, when early Muslims fled persecution and were welcomed by the Negus (Arabic: ٱلنَّجَاشِيُّ, al-Najāshī) of Abyssinia. The town of Negash, located in eastern Tigray, is considered one of the earliest Muslim settlements in Africa, and its restored Al Nejashi Mosque (the oldest in Ethiopia) remains a prominent religious site.[71]

Over the centuries, Sunni Muslim communities became integrated into the social and cultural fabric of Tigray, and they are now concentrated in border regions near Agame, Gulomahda, Shire, and Humera, where interaction with the Sudanese, Beja, and Saho was common.[230] Among them are the Jeberti, a Tigrinya-speaking Muslim group also present in Eritrea, often considered among the oldest Islamized populations in the Horn of Africa.[231][232] These communities traditionally follow Sunni Islam and maintain institutions such as madrasas, Sufi lodges, and local shrines.[233]

Despite being a minority, Tigrayan Muslims have generally coexisted peacefully with their Christian neighbors, although they experienced marginalization during periods when Orthodoxy was the state religion. In multi-religious cities like Adigrat and Shire, interfaith marketplaces, communal celebrations, and even intermarriage were historically not uncommon.[234][235]

In more recent times, since the adoption of Ethiopia’s current federal constitution has granted religious freedom, Muslim communities in Tigray have maintained their religious institutions and participate more actively in regional life, often in alignment with national Islamic councils rather than region-specific ethnic platforms.[234]

Culture

[edit]

Tigrayans are sometimes described as “individualistic”, due to elements of competition and local conflicts.[236] This, however, rather reflects a strong tendency to defend one's own community and local rights against—then widespread—interferences, be it from more powerful individuals or the state. Tigrayans communities are marked by numerous social institutions with a strong networking of character, where relations are based on mutual rights and bonds. Economic and other support is mediated by these institutions. In the urban context, the modern local government have taken over the functions of traditional associations. In most rural areas, however, traditional social organizations are fully in function. All members of such an extended family are linked by strong mutual obligations.[237] Villages are usually perceived as genealogical communities, consisting of several lineages.[5]

A remarkable heritage of Tigrayans are their customary laws. In Tigray, customary law is also still partially practiced to some degree even in political self-organization and penal cases. It is also of great importance for conflict resolution.[238]

The daily life of Tigrayans is highly influenced by religious concepts. For example, the Christian Orthodox fasting periods are strictly observed, especially in Tigray; but also traditional local beliefs such as in spirits, are widespread. In Tigray the language of the church remains exclusively Ge’ez. Tigrayan society is marked by a strong ideal of communitarianism and, especially in the rural sphere, by egalitarian principles. This does not exclude an important role of gerontocratic rules and in some regions such as the wider Adwa area, formerly the prevalence of feudal lords, who, however, still had to respect the local land rights.[5]

Cuisine

[edit]

Tigrayans food characteristically consists of vegetable and often very spicy meat dishes, usually in the form of tsebhi (Tigrinya: ፀብሒ), a thick stew, served atop injera, a large sourdough flatbread.[239] As the vast majority of Tigrayans belong to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (and the minority Muslims), pork is not consumed because of religious beliefs. Meat and dairy products are not consumed on Wednesdays and Fridays, and also during the seven compulsory fasts. Because of this reason, many vegan meals are present. Eating around a shared food basket, mäsob (Tigrinya: መሶብ) is a custom in the Tigray region and is usually done so with families and guests. The food is eaten using no cutlery, using only the fingers (of the right hand) and sourdough flatbread to grab the contents on the bread.[240][241]

Regional dishes

[edit]T'ihlo (Tigrinya: ጥሕሎ, ṭïḥlo) is a dish originating from the historical Agame and Akkele Guzai provinces. The dish is unique to these parts of both countries, but is now slowly spreading throughout the entire region. T'ihlo is made using moistened roasted barley flour that is kneaded to a certain consistency. The dough is then broken into small ball shapes and is laid out around a bowl of spicy meat stew. A two-pronged wooden fork is used to spear the ball and dip it into the stew. The dish is usually served with mes, a type of honey wine.[242]

Hilbet is a vegan cream dish, made from fenugreek, lentil and fava bean powder, typically served on injera with Silsi, tomatoes cooked with berbere.[243]

Contemporary era

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (July 2025) |

Genetics

[edit]Kumar, H R S et al. (2020), showed that Tigray samples from Northern Ethiopia had (~50%) of a genetic component shared with Europeans and Middle Eastern Populations.[244]

Notable Tigrayans

[edit]-

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the first ever African Director-General of the World Health Organization

-

Dawit Nega playing the guitar

A

[edit]- Abay Tsehaye - Co-founder of Tigray People's Liberation Front

- Abba Estifanos of Gwendagwende – Christian monk, itinerant preacher, and martyr known for his reformation movement and as an early dissident of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church

- Abeba Aregawi – runner and gold medalist of world, world indoor and European indoor

- Abebe Fekadu – Tigrayan-Australian powerlifter.

- Alemayehu Fentaw - Ethiopian constitutional law scholar, political theorist, conflict analyst, and a public intellectual.

- Ras Alula (Abba Nega) – 19th Century Ras of Ethiopia

- Abune Mathias – Patriarch and Catholicos of Ethiopia, Archbishop of Axum and Echege of the See of Takla Haymanot

- Abune Paulos – Former Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

- Ras Araya Selassie Yohannes - Son and first heir of Yohannes IV

- Araya Zerihun - Chairman of the Tigray Development Association

- Aster Gebrekirstos - Ethiopian scientist and professor of agroforestry at World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF).

- Aregawi Sabagadis - Dejazmach (governor) of Agame from 1831 to 1859.[245]

- Arkebe Oqubay – politician, a Minister and Special Advisor to the former Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Hailemariam Desalegn.

- Azeb Mesfin – Second First Lady of Ethiopia and widow of Meles Zenawi.

B

[edit]- Atse Baeda Maryam – Atse a pretender, son of Ras Mikael Sehul[246]

- Bereket Desta - Ethiopian athlete, competed during the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Berihu Aregawi - Long-distance runner and current world record holder in the 5000 m road race and the 10,000 m road race.

D

[edit]- Dawit Nega – Influential contemporary Tigrigna artist and singer

- Dawit Kebede – winner of the 2010 CPJ International Press Freedom Award.

- Debretsion Gebremichael – Governor of Tigray.

- Dejen Gebremeskel – long-distance runner who primarily competes in track events.

- Desta Hagos – First female painter in Ethiopia to hold a solo exhibition; landscapes and women's daily life

E

[edit]- Ewostatewos - Prominent monk, religious reformer, and saint.

- Eyasu Berhe – singer, writer, producer and poet, as well as a member of the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF).

- Eyeru Tesfoam Gebru – Professional cyclist from Aksum, rode for UCI Women's team, competed in World Championships & 2024 Olympics as Refugee Team

F

[edit]- Fetien Abay Abera – professor of crop science at Mekelle University and former President of Mekelle University.

- Ferede Aklum – A Mossad agent and Zionist activist best known for helping 900 Ethiopian Jews immigrate to Israel.

- Fisseha Desta – Vice President of Ethiopia

- Freweini Mebrahtu – the 2019 CNN Hero of the Year

- Freweyni Hailu – middle-distance runner and two-times gold medalist at the World Athletics Indoor Championships

- Fryat Yemane – Actress, television host and model.

G

[edit]- Gebregziabher Gebremariam – runner who won 5 times in the World Cross Country Championships

- Gebre Kristos Desta - Born to a Tigrayan father, he was a painter and poet credited with bringing modern art to Ethiopia.[247][248]

- Gebrehiwot Baykedagn – was an Ethiopian doctor, economist, and intellectual.

- Gebrehiwot Baykedagn – was one of the pioneer Ethiopian doctor, economist, and intellectual.

- Gebretsadik Abraha - athlete, gold medalist and record-breaker of the 2019 Guangzhou Marathon

- Gudaf Tsegay – athlete, 5,000 and 10,000 world champion, current world record holder for 5,000 m

- Gugsa Araya Selassie – army commander and Shum of Tigray Province

- Gotytom Gebreslase – athlete, marathon world champion

H

[edit]- Hagos Gebrhiwet – athlete and former World Junior Record holder in the 5,000 meters

- Haile Selassie Gugsa – Dejazmatch from Ethiopia

- Hayelom Araya – Ethiopian General of the army[249]

- Hayle Ibrahimov - Ethiopian-born Azerbaijani international middle and long distance track and field athlete

I

[edit]- Ilfenesh Hadera – American actress, her father is from Tigray

- Ileni Hagos – 19th century regent and mother of Ras Woldemichael Solomon of Hamassien

K

[edit]- Kindeya Gebrehiwot - Forestry professor and former president of Mekelle University. He advanced sustainable forest management in Tigray and advised the Ethiopian Ministry of Education

- Kinfe Abraham – Founder of Ethiopian Institute of Peace and former president of Horn of Africa Democracy and Development

- Kiros Alemayehu - Prolific songwriter and singer. Known for popularizing Tigrigna songs to non-Tigrinya speaking Ethiopians.

L

[edit]- Letesenbet Gidey - athlete, 10,000 meters world champion and multiple gold medalist, holds two world records.

M

[edit]- Mazor Bahaina – Israeli kes, Orthodox rabbi, and former politician, who served as a member of the Knesset for Shas

- Meles Zenawi – Former Prime Minister of Ethiopia

- Ras Mengesha Yohannes – "Natural" son and heir of Emperor Yohannes IV, later Ras of Tigray.

- Le'ul Ras Mengesha Seyoum - Governor-General of Tigray, and Minister of Public Works and Communications under Haile Selassie I

- Mercha Wolde Kidan – Shum Tembien and father of Emperor Yohannes IV

- Merid Wolde Aregay - Ethiopian historian and a scholar of Ethiopian studies.

- Mikael Sehul – Ras of Ethiopia

- Miruts Yifter – athlete who won two gold medals in the 1980 Moscow Olympics

- Mitiku Haile – Ethiopian researcher who was Professor of Soil Science at Mekelle University

- Mulugeta Gebrehiwot - Ethiopian peace researcher, and senior fellow at the World Peace Foundation, Tufts University.

- Mulu Gebreegziabher – Known as “Kashi Gebru", a feminist and TPLF fighter remembered for her bold advocacy against feudalism and patriarchy; executed under the Derg regime

- Mulu Hailemichael - cyclist, who last rode for UCI ProTeam Caja Rural–Seguros RGA.[250]

N

[edit]- Nahu Senay Girma - Women's rights activist, co-founder and executive director of the Association of Women in Boldness (AWiB), an NGO which trains women for leadership roles

R

[edit]- Reesom Haile [de] - Half-Tigrayan Eritrean poet, journalist and lecturer

- Rophnan – Famous musician and DJ who signed contracts with Universal Records

S

[edit]- Sabagadis Woldu - Shum of Agame and Governor of Tigray during the Zemene Mesafint

- Samora Yunis - Former Chief of General Staff of the ENDF

- Se'are Mekonnen - Former Chief of General Staff of the ENDF until his assassination in 2019.

- Sebhat Aregawi - Ras of Agame and son of Dejazmach Aregawi Sabagadis

- Sebhat Gebre-Egziabher – Ethiopian writer

- Selam Tesfaye – Actress, one of the most popular icon in the Ethiopian film industry and recipient of multiple awards.

- Seyoum Mengesha - Governor of Tigray and army commander during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and descendant of Yohannes IV

- Seyoum Mesfin - Co-founder of the TPLF, later became Ethiopia's Minister of Foreign Affairs and Ethiopia's Ambassador to China.

- Siye Abraha – leading the UN Development Programme's security sector reform in Liberia

T

[edit]- Tedros Adhanom – The Director General of World Health Organization[251]

- Tesfasellassie Medhin - Bishop of Ethiopian Catholic Eparchy of Adigrat

- Tewolde Berhan Gebre Egziabher – world-renowned environmental scientist

- Tilahun Gizaw – Main leader of the Ethiopian Student Movement which ultimately led to the Ethiopian Revolution

- Tsadkan Gebretensae – Lieutenant general and member of the central command of the Tigray Defense Forces

- Tsgabu Grmay – road cyclist, one-time African time trial champion

W

[edit]- Werknesh Kidane – runner who won a gold medal in the 2003 World Cross Country Championships

- Wolde Selassie – Ras of Ethiopia

Y

[edit]- Saint Yared – Axumite composer and priest, inventor of the three basic modes of Ethiopian/Eritrean church music, namely Ge'ez, Ezl, and Araray

- Yared Nuguse – American professional middle-distance runner bronze medalist in 1500m from the 2024 Summer Olympics.

- Yengus Azenaw - T47 para-athlete in sprints; represented Ethiopia at 2012 & 2016 Paralympics

- Abuna Yesehaq - leader of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church in the Western hemisphere.

- Yohannes IV – Emperor of Ethiopia born in Tembien, Ethiopian Empire

- Yohannes Abraham – He has been selected to lead the planned presidential transition for Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris.

- Yohannes Haile-Selassie – paleoanthropologist and curator of Physical Anthropology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History from 2002 until 2021, and current director of the Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins.

Z

[edit]- Zeresenay Alemseged – paleoanthropologist who was the Chair of the Anthropology Department at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, U.S.

- Zera Yecob - 17th century philosopher best known for his treatise, Hatata ("The Inquiry"), which explores themes of reason, morality, and religious tolerance.

Notes

[edit]- ^ A title often shared with Lalibela

- ^ This title means Father of Peace, the [[Illuminator (title)|]]

- ^ Their names were Abba Aftse, Abba Alef, Abba Aragawi, Abba Garima, Abba Guba, Abba Liqanos, Abba Pantelewon, Abba Tsahma and Abba Yem'ata

References

[edit]- ^ Ethiopian Statistical Service (September 2024). "Projected Population – 2024" (PDF). Ethiopian Statistical Service. Retrieved July 1, 2025.

- ^ Pagani, Luca; Kivisild, Toomas (July 2012). "Ethiopian Genetic Diversity Reveals Linguistic Stratification and Complex Influences on the Ethiopian Gene Pool". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 91 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.015. PMC 3397267. PMID 22726845.

- ^ Prunier, Gerard; Ficquet, Eloi (2015). Understanding contemporary Ethiopia. London: Hurst & Company. p. 39. OCLC 810950153.

- ^ Levine, Donald N. (2000). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226475615. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Smidt, Wolbert (2007). "Tigrayans". In Uhlig, Siegbert (ed.). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ^ Shinn, David; Ofcansky, Thomas (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 378–380. ISBN 978-0-8108-4910-5.

- ^ Ullendorff, Edward (1973). The Ethiopians. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 31, 35–37.

- ^ "Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census" (PDF). Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. 2008. Retrieved 2025-07-14.

- ^ Abbink, Jon (2013). "Religion in Public Spaces: Emerging Muslim–Christian Polemics in Ethiopia". African Affairs. 112 (446): 253–274. doi:10.1093/afraf/adt008.

- ^ Shaban, Abdurahman. "One to five: Ethiopia gets four new federal working languages". Africa News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Gragg, Gene B. (1997). Robert Hetzron (ed.). Tigrinya. Routledge. pp. 425–445.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Phillipson, David W. (2012). Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC–AD 1300. James Currey.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat (1972). Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527). Oxford University Press. pp. 98–99.

- ^ Young, John (1997). Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia: The Tigray People's Liberation Front, 1975–1991. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Vaughan, Sarah (2003). Ethnicity and Power in Ethiopia. University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2025-07-14.

- ^ Levine, Donald N. (1972). "The Concept of "Greater Ethiopia"". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 10 (3): 367–376. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00024756 (inactive 18 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Marcus, Harold G. (1994). A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press.

- ^ a b Ptolemy, Geographia, Book 4, Chapter 7; see also: Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People, Oxford University Press, 1965, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972, p. 1.

- ^ Ptolemy, Geographia, Book 4.7.27; cf. Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopians: A History, Blackwell, 2001, p. 21.

- ^ R.H. Tappe, "The Location of Ancient Coloe," in The Geographical Journal, Vol. 123, No. 4 (1957), pp. 451–454.

- ^ A. J. Arkell, "The Location of Coloe", in Sudan Notes and Records, Vol. 38 (1957), pp. 100–102.

- ^ R. Pankhurst, The Ethiopians: A History, Oxford: Blackwell, 2001, p. 21.

- ^ a b c M.J. de Goeje, ed., Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 6: Ibn Khurradādhbih, Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik (Leiden: Brill, 1889), p. 6.

- ^ a b Al-Yaʿqūbī, Kitāb al-Buldān, ed. M.J. de Goeje, in: Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 7 (Leiden: Brill, 1892), pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b Ibn Ḥawqal, Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ, ed. Kramers and Wiet (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 1964), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Al-Maqdisī, Aḥsan al-Taqāsīm fī Maʿrifat al-Aqālīm, ed. M.J. de Goeje, in: Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 3 (Leiden: Brill, 1877), pp. 227–229.

- ^ Al-Idrīsī, Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq, ed. G. Ferrand, Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1927, vol. 1, p. 46.

- ^ Enrico Cerulli, Etiopia Occidentale, vol. II: La Storia, Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1956, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991, p. 260.

- ^ Levine, Donald N., Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society, University of Chicago Press, 1974, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Trimingham, J. Spencer. Islam in Ethiopia. London: Frank Cass, 1952, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Fauvelle, François-Xavier. Le royaume chrétien d’Éthiopie: Des origines à l’âge d’or. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2017, pp. 154–158.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972, pp. 20–23.

- ^ a b Trimingham, J. Spencer. Islam in Ethiopia. London: Frank Cass, 1952, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Cerulli, Enrico. Etiopia Occidentale, vol. 1. Rome: Istituto per l'Oriente, 1943, p. 35.

- ^ M.J. de Goeje (ed.), Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik by al-Iṣṭakhrī, in: Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 1, Leiden: Brill, 1870, p. 7.

- ^ Fauvelle, François-Xavier. Le royaume chrétien d’Éthiopie: Des origines à l’âge d’or. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2017, pp. 155–158.

- ^ Al-Istakhri, Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik, in: M.J. de Goeje, ed., Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 1 (Leiden: Brill, 1870), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-’Arḍ, in: M.J. de Goeje, ed., Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 2 (Leiden: Brill, 1873), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Al-Maqdisī, Aḥsan al-Taqāsim fī Maʿrifat al-Aqālīm, in: M.J. de Goeje, ed., Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, vol. 3 (Leiden: Brill, 1877), pp. 354–356.

- ^ Al-Idrisi, Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq, ed. G. Ferrand, in: Recueil de documents sur l’histoire de la géographie musulmane, Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1927.

- ^ a b Wolska-Conus, Wanda. Cosmas Indicopleustès: Topographie Chrétienne, vol. 1, Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1968, commentary and notes on Book 2, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Perruchon, Jules. Chronique du roi Amda Sion. Paris: Leroux, 1894.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat. Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.

- ^ Francisco Álvares, The Prester John of the Indies, trans. and ed. Lord Stanley of Alderley, Hakluyt Society, 1881, pp. 193–205.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopians: A History. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Jerónimo Lobo, A Voyage to Abyssinia, trans. Samuel Johnson, London: 1735, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Boxer, Charles R. The Christian Century in Japan: 1549–1650. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951, Appendix D.

- ^ Hiob Ludolf, Historia Aethiopica, Frankfurt: 1681, pp. 26–28, 47–50.

- ^ Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence. London: Heinemann, 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Poncet, Charles Jacques. A Voyage to Ethiopia, Made in the Years 1698, 1699 and 1700. In: Churchill, Awnsham and John (eds.). A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. 1. London: Churchill, 1732, pp. 705–715.

- ^ Lobo, Jerónimo. The Itinerário: Voyage to Abyssinia. Translated by Donald M. Lockhart. London: Hakluyt Society, 1984 [original Portuguese manuscript c. 1620s–1630s], pp. 98–102, 143–145.

- ^ de Almeida, Manuel. The History of High Ethiopia or Abassia. Translated by C.F. Beckingham and G.W.B. Huntingford. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1954 [written c. 1624–1634], pp. 114–117, 140–150.

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, Éthiopie ou Abissinie, in: Atlas général, Paris: 1757.

- ^ Willem Blaeu, Africa Nova Tabula, Amsterdam: 1645.

- ^ Ortelius, Abraham. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Antwerp: 1570.

- ^ Bruce, James (1860). Bruce's Travels and Adventures in Abyssinia. p. 83.

- ^ Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Charles Knight. 1833. p. 53.

- ^ Salt, Henry (1816). A Voyage to Abyssinia. M. Carey.

- ^ a b Salt, Henry (1816). A Voyage to Abyssinia. M. Carey. pp. 378–382.

- ^ Henry Salt A Voyage to Abyssinia. Published in 1816 pp. 378–382 Google Books

- ^ Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Charles Knight. 1833. p. 53.

- ^ The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: Bassantin – Bloemaart, Volume 4. Charles Knight. 1835. p. 170.

- ^ Hetzron, Robert. "The Semitic Languages." Routledge, 1997.

- ^ Gragg, Gene B. "Tigrinya." In The Semitic Languages, edited by Robert Hetzron, 425–445. Routledge, 1997.

- ^ a b c Ullendorff, Edward. The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People. Oxford University Press, 1960.

- ^ Amanuel Sahle. “Ethiopia: A Historical Perspective of the Ethnic Composition of Tigray.” Africa Spectrum, vol. 20, no. 2 (1985), pp. 123–135.

- ^ Phillipson, David W. Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300. James Currey, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Munro-Hay, Stuart. Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press, 1991.

- ^ Leslau, Wolf. Etymological Dictionary of Ethiopian Semitic. Otto Harrassowitz, 1987.

- ^ a b c d Ullendorff, Edward. The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People. Oxford University Press, 1965.

- ^ a b Hetzron, Robert. The Semitic Languages. Routledge, 1997.

- ^ Ferguson, Charles A. “Ethiopian Language Area.” International Journal of American Linguistics, vol. 30, no. 3, 1964.

- ^ Bender, Lionel M. “The Languages of Ethiopia.” Oxford University Press, 1976.

- ^ Kapeliuk, Olga. “The Semitic Languages of Ethiopia.” In The Semitic Languages, ed. Hetzron, 404–423.

- ^ a b c d Taddesse Tamrat. Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527). Clarendon Press, 1972.

- ^ Crummey, Donald. Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: From the Thirteenth to the Twentieth Century. James Currey, 2000.

- ^ a b Finneran, Niall. The Archaeology of Ethiopia. Routledge, 2007.

- ^ Bayne, Samuel G. On the Track of the Ancient Ethiopians. London: J. Lane, 1910.

- ^ Beke, Charles T. "On the Origin of the Galla and the Rise of the Amharic Language." Journal of the Ethnological Society of London, vol. 1, 1846, pp. 45–61.

- ^ Bruce, James. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile. Edinburgh: 1790.

- ^ Salt, Henry. A Voyage to Abyssinia. London: 1814.

- ^ Waldmeier, Theophilus. Ten Years in Abyssinia. London: 1868.

- ^ Ullendorff, Edward. The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People. Oxford University Press, 1960, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Conti Rossini, Carlo. "Etiopia e Galla." In: Rendiconti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei, 1910.

- ^ Trimingham, J. Spencer. Islam in Ethiopia. London: Frank Cass, 1952, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kapeliuk, Olga. "The Semitic Languages of Ethiopia." In The Semitic Languages, ed. R. Hetzron, Routledge, 1997.

- ^ a b Weninger, Stefan. The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. De Gruyter Mouton, 2011, pp. 1028–1030.

- ^ a b c Leslau, Wolf. Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification. University of California Press, 1952.

- ^ Weninger, Stefan. "Tigrinya." In The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook, edited by Stefan Weninger, De Gruyter Mouton, 2011, pp. 1028–1030.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart. Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press, 1991.

- ^ Fiaccadori, Gianfranco. "Aksum." In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 1, ed. Siegbert Uhlig, Harrassowitz, 2003, pp. 185–192.

- ^ Bausi, Alessandro. “The Geʽez Script and Its Role in Ethiopian Identity.” In Africana Studia, no. 28, 2017, pp. 17–34.

- ^ Finneran, Niall. The Archaeology of Ethiopia. Routledge, 2007, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Ullendorff, Edward. The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People. Oxford University Press, 1965, pp. 70–73.

- ^ Bender, M. Lionel. "The Limits of Tigrinya as a Tool for Understanding Ethiopian Ethnohistory." In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Ethiopian Studies, 1980, pp. 349–360.

- ^ Weninger, Stefan. “Tigre and Tigrinya.” In The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook, edited by Stefan Weninger, De Gruyter Mouton, 2011, pp. 1028–1045.

- ^ Weninger, Stefan. "Tigrinya." In The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook, ed. Stefan Weninger, De Gruyter Mouton, 2011, pp. 1028–1030.

- ^ Kaplan, Steven. "Tigrayans." In Siegbert Uhlig (ed.), Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 4, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2010, pp. 886–888.

- ^ Levine, Donald N. Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- ^ Gragg, Gene B. "Tigrinya." In: Hetzron, Robert (ed.). The Semitic Languages, Routledge, 1997.

- ^ Kapeliuk, Olga. “The Semitic Languages of Ethiopia.” In: Hetzron, Robert (ed.), The Semitic Languages, pp. 404–423.

- ^ National Geographic (3 December 2018). "In search of the real Queen of Sheba, Legends and rumors trail the elusive Queen of Sheba through the rock-hewn wonders and rugged hills of Ethiopia". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ a b Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), p. 36

- ^ a b Erlich, Haggai (2024). Greater Tigray and the Mysterious Magnetism of Ethiopia. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-776933-1.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart (1991). 'Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press.

- ^ Shaw, Thurstan (1995), The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns, Routledge, p. 612, ISBN 978-0-415-11585-8, archived from the original on 27 March 2023, retrieved 10 July 2017

- ^ Rodolfo Fattovich (1994). "The Rise of the Kingdom of D'mt and the Archaeological Evidence of Early Ethiopian Civilization". The Journal of African Archaeology. 12 (1): 43–62.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Rodolfo Fattovich (2009). "The Red Sea and Its Role in the Formation of Early Ethiopian Civilizations". The Mediterranean Journal of Archaeology. 22 (3): 50–72.

- ^ Joseph Michels (1967). "D'mt and Its Sabaean Connections". Ethiopian Studies Review. 5 (1): 21–37.

- ^ Stanley Burstein (1984). "The Kingdom of D'mt and the Development of Ancient Ethiopian Culture". Journal of African History. 25 (2): 15–30.

- ^ Munro‑Hay, Stuart. Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press, 1991, p. 187.

- ^ Phillips, Jacke. “The Foreign Contacts of Ancient Aksum: New finds and some random thoughts.” *Journal of African Archaeology*, 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Peacock, David P.S. and A.J. Blue. “The Ancient Red Sea Port of Adulis, Eritrea.” *International Journal of Nautical Archaeology*, 2007, p. [insert specific page].

- ^ “Indian Ocean and Africa.” *Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History*, Oxford University Press, 2021, para. 1.

- ^ Fattovich, R. (2009). "The Red Sea and Its Role in the Formation of Early Ethiopian Civilizations". The Mediterranean Journal of Archaeology. 22 (3): 50–72.

- ^ a b c Taddesse, M. (2012). The Zagwe Dynasty and the Evolution of Ethiopian Christianity. Addis Ababa University Press.

- ^ Phillipson, David W. (2012). Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC–AD 1300. James Currey. pp. 147–149.

- ^ Pankhurst, R. (1997). A History of Ethiopia. Lalibela Press.

- ^ a b c Kaplan, Steven (2009). The Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia. Studien zur Kulturkunde. pp. 35–42.

- ^ Sergew Hable Sellassie (1972). Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "The Tigray Crisis and the Possibility of an Autocephalous Tigray Orthodox Tewahdo Church". 30 July 2021. Retrieved 2025-04-26.

- ^ a b Rubenson, Sven (1976). The Survival of Ethiopian Independence. London: Heinemann. pp. 25–27.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1998). The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles. Addis Ababa University Press. pp. 5–7.

- ^ Bowersock, Glen W. (2013). The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0199739325.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat. Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972, pp. 35–40.

- ^ Kaplan, Steven. "The Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia." In Studia Patristica, vol. 18, 1989.

- ^ Hubbard, J.R. "Ethiopia and the Legend of the Solomonic Dynasty." Journal of Ethiopian Studies 6, no. 1 (1968): 23–33.

- ^ Marcus, Harold G. A History of Ethiopia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), p. 19.