The Three Dead and the Three Living

The Three Living and the Three Dead (also known as The Three Dead and the Three Quick,[1] French: Le Dit des trois Morts et des trois Vifs, tale or legend) is a theme in Medieval visual arts (painting, miniature, illumination, and sculpture) that shows three corpses addressing three young, richly adorned pedestrians (or three young horsemen), often while they are hunting. This theme became popular during the 14th and 15th centuries.

The theme

[edit]

The theme of The Three Living and the Three Dead is not death itself—in this case, that of the three young men—as in memento homo, the Triumph of Death, the Ars moriendi, vanitas paintings, memento mori, or the Danse Macabre, which depicts death leading a hierarchical procession of the living. Instead, it is a lesson, a warning of a decomposition, a decay to come in a more or less distant future.

Michel Vovelle notes, however, that the story's argument is "simple in its brutality": three young hunters are confronted by three dead figures in different states of decomposition. They have a brief but essential exchange:

...Itel con tu es itel fui / Et tel seras comme je suis[2]

As you are, so I was / And as I am, so you will be

The first known text relating to The Tale of the Three Living and the Three Dead, preserved at the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, dates from the 1280s and begins with a miniature.[M 1]

The oldest painted representation outside of a manuscript, also from the 13th century, was likely the one in the Sainte-Ségolène Church of Metz, which disappeared during the building's restoration between 1895 and 1910. It was also the subject of two frescoes in the 13th-century church of the former Abbaye Saint-Étienne de Fontenay, near Caen, which was demolished in 1830. There is a still-visible fresco in the church of Ennezat (Puy-de-Dôme); enriched with phylacteries, this painting dates from the 15th century. A 15th-century fresco was discovered in 1957 under whitewash in the church of Saint-Martin in Gonneville-sur-Honfleur (Calvados).

Ashby Kinch reports[3] a note in an account book regarding the purchase in London of a diptych of the legene famosa dei tre morte e dei tre vivi by Count Amadeus V of Savoy; the wording of this transaction, between May 1302 and July 1303, suggests that the image, and therefore its legend, was known in the context of devotional images widespread at the time.

Texts

[edit]According to Stefan Glixelli,[4] there are five variants of the legend, found in about twenty manuscripts[5] They are numbered as follows:

- Poem I: Ce sont li troi mort et li troi vif, by Baudouin de Condé, active between 1240 and 1280. Present in six manuscripts.

- Poem II: Chi coumenche li troi mort et li troi vif, by Nicolas de Margival. Present in two manuscripts.

- Poem III: Ch'est des trois mors et des trois vis, anonymous author. Present in a single manuscript.

- Poem IV: C'est des trois mors et des trois vis (same opening), anonymous author. Present in seven manuscripts.

- Poem V: Cy commence le dit des trois mors et des trois vis, anonymous author. Present in six manuscripts.

Library Manuscript Poem Pages Paris BnF Fr. 25566 Poem I fol. 217-218 Poem II fol 218-219v Poem III fol. 223-224v. Paris BnF Fr. 378 Poem I fol. 1 Poem IV fol. 7v-8 Paris Arsenal 3142 Poem I fol. 311v-312. Paris BnF Fr. 1446 Poem I fol. 144v-145v. Paris Arsenal 3524 Poem I fol. 49-50v. Paris BnF Fr. 25545 Poem I fol. 106v-108. Paris BnF Fr. 1109 Poem II fol. 327-328. The Cloisters Inv. 69. 86 Poem IV fol 320-326v London British Library Egerton 945 Poem IV fol. 12-15v. Paris BnF Fr. 2432 Poem IV fol. 13v-14.[6] Arras, Bibl. mun. 845 Poem V fol. 157. Paris BnF Fr. 1555 Poem V fol. 218v-221. Cambridge, Magdalene College coll. Pepys 1938 Poem IV Paris BnF Lat. 18014[7] Poem IV fol. 282-286[M 2] London British Library Arundel 83 Poem IV fol 127. Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium 10749-50[8] Poem V fol. 30v-33v Paris, BnF Fr. 995 Poem V fol. 17v-22v Chantilly, Musée Condé 1920 Poem V Lille, Bibl. mun. 139 Poem V fol. 10v-13v

The collection of the manuscript BnF Ms 25566[M 3] alone contains three different versions. The first two texts are roughly contemporary[9]:

The text by Baudouin de Condé (active 1240 to 1280) which accompanies the engraving preserved at the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal.[M 1] In twenty-six lines, the introduction presents the three Living, who are a prince, a duke, and a count, suddenly spotting the three horrible Dead. Each of the Living then speaks to describe the unbearable vision and to understand the lesson given to their pride... The first of the Dead affirms that they too will become as hideous as them, the second blames the wickedness of death and complains of hell, the third insists on the precariousness of life and the need to be ready for the inevitability of death. This poem concludes with four lines addressed by the dead to the living:

Pries pour nous au patre nostre

S'en dites une patrenostre

Tout vif de boin cuer et de fin

Que Diex vous prenge a boine fin.

— Pray for us with the Our Father

Say a Pater Noster for it

May God bring you to a good end.

Every living soul with a good and pure heart

The Dit by Nicolas de Margival (late 13th century)[M 3] presents the three young men as full of pride, from powerful royal, ducal, and comital families. God, wishing to warn them, brings them before three emaciated dead figures. Each character then speaks, and in the conclusion, the dead leave the living pale and frightened, having learned the moral: "Let us lead a life that pleases God, let us beware of going to hell, let us know that death will seize us too, and let us pray to Our Lady that, at the hour of our death, she will be near her son."

Other editions, with the same title, appear, for example, in a manuscript of the Roman de la Rose.[M 4]

Anatole de Montaiglon compiled the texts of the five versions in a work decorated with engravings by Hans Holbein.[10] This volume, published in 1856, is accessible online and has also been reissued in a more spacious layout.[11]

Iconography

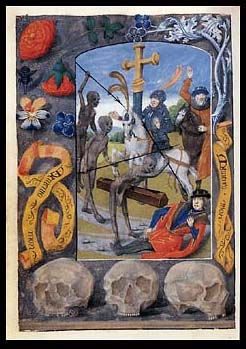

[edit]The local variations in representation do not allow for a precise tracing of the iconography's evolution. However, the earliest iconographies depict the young men on foot until the mid-14th century. After this date, they appear as horsemen. Falcons and dogs are almost constant: the legend itself requires the presence of three rich and powerful lords, and the hunting party best highlights this aspect.[12][13][14] While the three Living are identically dressed, a gradation is often observed in the representation of the three Dead: the first skeleton and its shroud are in fairly good condition, the second's shroud is in tatters, while the third's has almost disappeared. The three Dead are usually standing, emerging from the cemetery in a striking effect of surprise, and may be equipped with scythes, bows, arrows... The cross—that of the cemetery—at the center of the composition separates the two groups of characters; it is part of the legend, which is sometimes narrated by Macarius of Egypt, who then appears in the depiction.

The representation varies over time. The earliest are rather simple. Three dead figures, in a static pose, stand in the path of three lords traveling on foot, as in the poem by Baudouin de Condé from the Arsenal[M 1] or that of Nicolas de Margival.[M 3] In the Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg,[E 1] from 1348-1349, illustrated on a double page by Jean Le Noir, the nobles are on horseback and the dead, standing in graves, represent three different stages of decomposition. A simple calvary can mark the boundary between the world of the dead and the living, as in the bas-de-page of the funeral of Raymond Diocres in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.[E 2]

In the Book of Hours of Edward IV, it is the dead who attack the living, one of whom is on the verge of death.[E 3]

At the end of the Middle Ages, books of hours were produced in quantity, a development accentuated by printing and xylography,[9] and the legend is frequently present in the illustration at the beginning of the Office of the Dead.

-

Manuscript of the Roman de la Rose BnF Ms 378 fol. 1r.

-

Manuscript of the Roman de la Rose BnF Ms 378 fol. 7v.

-

Jean Le Noir, Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg, The Cloisters, Inv. 69. 86, fol. 321v-322r.

Wall paintings

[edit]The Research Group on Wall Paintings (Groupe de recherche des peintures murales) has identified 93 wall paintings in France[13]; there are as many in the rest of Europe. In the Avignon Cathedral, a fresco of The Tale of the Three Living and the Three Dead was uncovered, where the characters are placed under individual arches. This fresco frames another macabre work, where Death riddles people massed to its right and left with arrows. The paleographic study of the inscription above it, which gives the name of the donor Pierre de Romans, has made it possible to date the ensemble to the second half of the 13th century. This makes this group of macabre frescoes one of the oldest works of its kind in Europe.[15]

The following non-exhaustive list is taken from the work of Hélène and Bertrand Utzinger:[12]

In France

[edit]- Alluyes (Eure-et-Loir)

- Amilly (Eure-et-Loir)

- Amponville (Seine-et-Marne), Fromont

- Les Autels-Villevillon (Eure-et-Loir)

- Antigny (Vienne)

- Auvers-le-Hamon (Sarthe)

- Avignon, Notre-Dame-des-Doms Cathedral

- Barneville-la-Bertran (Calvados)

- La Bazouge-de-Chemeré (Mayenne)

- Bonnet (Meuse)

- Briey (Meurthe-et-Moselle)

- Carennac (Lot)

- Charmes (Vosges)

- Chassignelles (Yonne) (almost erased)

- Chassy (Cher)

- Chemiré-le-Gaudin (Sarthe)

- Conan (Loir-et-Cher)

- Courgenard (Sarthe)

- Courgis (Yonne)

- Dambach-la-Ville (Bas-Rhin)

- Dannemarie (Yvelines)

- Ennezat (Puy-de-Dôme)

- Château d'Époisses, at Époisses (Côte-d'Or)

- Ferrières-Haut-Clocher (Eure)

- La Ferté-Loupière (Yonne)

- La Ferté-Vidame (Eure-et-Loir)

- Gonneville-sur-Honfleur (Calvados)

- Guerchy (Yonne)

- Heugon (Orne)

- Jouhet (Vienne)

- Kientzheim (Haut-Rhin)

- Lancôme (Loir-et-Cher), Saint-Pierre church

- Lindry (Yonne)

- Lugos (Gironde)

- Meslay-le-Grenet (Eure-et-Loir)

- Mœurs-Verdey (Marne) Saint-Martin de Mœurs church

- Migennes (Yonne)

- Moitron-sur-Sarthe (Sarthe), Templar commandery of Gué-Lian

- Mont-Saint-Michel (Manche), Mont-Saint-Michel Abbey

- Nostang (Morbihan)

- Plouha (Côtes-d'Armor), Chapel of Kermaria an Iskuit (also has a Danse Macabre)

- Rocamadour (Lot)

- Saint-Fargeau (Yonne)

- Saint-Riquier (Somme), treasury room of the abbey church

- Saulcet (Allier)

- Senlis (Oise)

- Sepvigny (Meuse), chapel of Vieux-Astre

- Villiers-Saint-Benoît (Yonne)

- La Romieu (Gers)

- Verneuil, Saint Laurent Church

- Villiers-sur-Loir (Loir-et-Cher)

-

The "Tale of the Three Living and the Three Dead," Saint-Pierre church, Lancôme (Loir-et-Cher).

-

The "Tale of the Three Living and the Three Dead," Saint Germain church, La Ferté-Loupière (Yonne).

-

The fresco in the chapel of Kermaria an Iskuit (Côtes-d'Armor).

-

The fresco in the chapel of Vieux-Astre (Meuse).

-

Fresco of the collegiate church of Ennezat.

In Germany

[edit]In the Alemannic-speaking regions—Alsace, Baden, the Lake Constance region, Swabia, as well as German-speaking Switzerland—there are some local variations in representation: the living approach on foot and suddenly find themselves opposite the three dead; no cemetery cross separates the two groups of characters.[16][17]

- Badenweiler (c. 1380)

- Chammünster (15th c.)

- Eriskirch (1430-1440)

- Überlingen (after 1424)

- Wismar (14th c.)

In Switzerland

[edit]- Basel Saint-Jacques (1420)

- Breil/Brigels (1451)

- Orbe (15th century)

- Sempach - Kirchbühl (c. 1310)

In Belgium

[edit]In Denmark

[edit]- Bregninge

- Kirkerup

- Skibby

- Tüse

In Italy

[edit]

- Albugnano, Abbey of Vezzolano

- Bosa

- Melfi, Rupestrian church of Santa Margherita (13th c.)

- Pisa

- Subiaco, Monastery of Saint Benedict (Sacro Speco)

In the Netherlands

[edit]- Zaltbommel

- Zutphen

See also

[edit]- The quick and the dead, an English phrase

- The Three Dead Kings, a poem

Notes and references

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Murray & Murray 1998.

- ^ Vovelle, Michel (1996). Les âmes du purgatoire ou le travail du deuil. Le temps des images (in French). Paris: Gallimard. p. 28. ISBN 978-2-070-73816-8.

- ^ Kinch 2013, p. 122-123.

- ^ Glixelli 1914.

- ^ Pollefeys 2014.

- ^ and fragment fol 246v of the Dit des trois mortes et des trois vives.

- ^ Petites Heures de Jean de Berry

- ^ Record on KBR.

- ^ a b Cassagnes-Brouquet, Sophie (1998). Culture, artistes et société dans la France médiévale (in French). Gap: Ophrys. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-2-7080-0869-4.

- ^ de Montaiglon 1856.

- ^ de Montaiglon & Holbein 2013.

- ^ a b Utzinger, Hélène; Utzinger, Bertrand (1996). Itinéraires des Danses macabres (in French). Chartres: éditions J.M. Garnier. ISBN 2-908974-14-2..

- ^ a b Vifs nous sommes... morts nous serons: la rencontre des trois morts et des trois vifs dans la peinture murale en France (in French). Vendôme: Éditions du Cherche-Lune. 2001. ISBN 2-904736-20-4— Work written by the eight researchers L. Bondaux, M.-G. Caffin, V. Czerniak, Chr. Davy, S. Decottignies, I. Hans-Colas, V. Juhel, Chr. Leduc.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Review: Terrier-Fourmy, Bérénice (2002). "Groupe de recherches sur les peintures murales, Vifs nous sommes... morts nous serons. La rencontre des trois morts et des trois vifs dans la peinture murale en France. Vendôme, Cherche-Lune, 2001". Bulletin Monumental (in French). 160 (4): 427–428..

- ^ Dit des trois morts et des trois vifs sur le site lamortdanslart.com

- ^ Rotzler, Willy (1961). Die Begegnung der drei Lebenden und der drei Toten: Ein Beitrag zur Forschung über die mittelalterlichen Vergänglichkeitsdarstellungen (in German). Winterthur: P. Keller. (Dissertation Basel 1961).

- ^ Wehrens, Hans Georg (2012). Der Totentanz im alemannischen Sprachraum. "Muos ich doch dran und weis nit wan" (in German). Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner. pp. 25–35. ISBN 978-3-7954-2563-0..

- Manuscripts

- ^ a b c BnF Ms. 3142 Recueil d'anciennes poésies françaises, folios 311v and 312r.

- ^ Petites Heures de Jean, duc de Berry on Gallica.

- ^ a b c Chansonnier et mélanges littéraires « Li iii mors et li iii vis » (BnF Ms 25566 fol. 217-219) contains a version by Baudouin de Condé and one by Nicolas de Margival. A third appears a little further in the collection, at folios 223-224v.

- ^ Manuscript of the Roman de la Rose, BnF, Ms. Fr. 378 (1280-1300). Two versions appear on folios 1-1v and 7v-8v. The first is by Baudouin de Condé. Both texts are preceded by small colored miniatures.

- Illuminations

- ^ Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg The Cloisters Collection, acc. no. 69.86.

- ^ Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Musée Condé, Chantilly, Ms. 65, folio 86v.

- ^ Maître d'Édouard IV, Book of Hours, use of Rome, Bruges, late 15th c. Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department, Lewis E 108, f. 109v.

Bibliography

[edit]- de Montaiglon, Anatole (1856). Alphabet de la mort de Hans Holbein (in French). Pour Edwin TrossPoems framed by Holbein's woodcuts. Commented on blogscd.paris-sorbonne.fr/2011/09/lalphabet-de-la-mort-holbein (Le blog Paris-Sorbonne).]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - de Montaiglon, Anatole; Holbein, Hans (2013). Alphabet de la mort, suivi de « Les Trois Morts et les Trois Vifs » (in French). Villers-Cotterêts: Ressouvenances. ISBN 978-2-84505-124-9.

- Johan Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages : in "The Vision of Death", Paris, Payot, 1919, pp. 164-180.

- Glixelli, Stefan (1914). Les cinq poèmes des trois morts et des trois vifs (in French). Paris: Librairie ancienne Honoré Champion, éditeur.

- Kinch, Ashby (2013). "Chapter 3. Commemorating Power in the Legend of the Three Living and Three Dead (p. 109-144)". Imago mortis : mediating images of death in late medieval culture. Visualizing the Middle Ages. Vol. 9. Leiden: Brill. pp. 121–122. doi:10.1163/9789004245815. ISBN 978-90-04-24581-5.

- Künstle, Karl (2013). Die Legende der drei Lebenden und der drei Toten und der Totentanz (in German). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24581-5.

- Murray, Peter; Murray, Linda (1998). "Dance of Death". The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-19-860216-3. OCLC 1055176997.

- Pollefeys, Patrick (2014). "Dit des trois vifs et des trois morts". La Mort dans l’art (in French). Retrieved 2 May 2015..

External links

[edit]- Biggs, Sarah J. (16 January 2014). "The Three Living and the Three Dead". Medieval manuscripts blog. British Library. Retrieved 20 June 2025.

![The fresco in the chapel of Vieux-Astre [fr] (Meuse).](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Meuse%2C_Sepvigny%2C_chapelle_du_vieux_Astre_01.jpg/330px-Meuse%2C_Sepvigny%2C_chapelle_du_vieux_Astre_01.jpg)