Saint-Barthélemy affair

| Saint-Barthélemy affair | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 garnisson 1 schooner 1 smaller vessel 1 brig | 1 naval squadron | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| none |

1 killed 4 executed +3 ships seized several ships damaged | ||||||

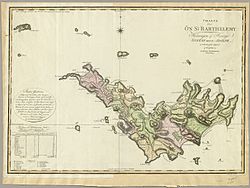

During the early 19th century as a consequence of the various wars that had erupted all over the world, piracy in the Caribbean saw an uptick as pirates and privateers took advantage of the situation. Located at the heart of such activities was the Swedish colony of Saint Barthélemy. With its numerous hideouts and laid-back administration, it became an important hub for piracy in the region. However, after the island's governor, Johan Jean Norderling, had received strong criticism for allowing such activities, he took additional measures to clamp down on pirates within the island.

In the following few months, Norderling had captured numerous pirate ships with his makeshift fleet. However, due to an incident with a French fleet during the capture of a pirate ship, the two parts came into conflict. The French blockaded the colony but hostilities remained short-lived as higher ranking French generals made peace with the Swedes.

In the end, several pirates would be tried and their stolen goods would be returned to their original owners.

Background

[edit]As a consequence of the outbreak of various wars of independence across the Americas during the Napoleonic wars, piracy and privateering became a serious problem around the Caribbean.[1][2] Especially so in and around the island of Saint Barthelemy due to its numerous hideouts and location.[3][1] The island's governor, Johan Jean Norderling, did not take any significant action against the pirates on the island, as they were good for the local economy, which had been struggling since the end of the Napoleonic wars.[4][1] Furthermore, the pirates generally did not harm locals.[3] Nevertheless, Nordling received heavy criticism from the United States of America, which accused Norderling of aiding the pirates in the Antilles.[4][5][1] Relations with the United States worsened as Norderling--as ordered by Karl XIV Johan--refused to let the Americans establish a consulate in the islands' capital, Gustavia.[1][2][5] Norderling assured the American representative, Aslop, that Saint-Barthelemy did not give sanctuary to privateers of any side of the Latin American wars of independence and that Sweden-Norway would continue to remain neutral.[2][6] Norderling also promised that if any privateers were found on the small island of Fourchue (a notable pirate hub in Saint-Barthelemy), he would drive them away.[2][6][1][5]

Anti-piracy operations

[edit]Saint-Barthelemy did not have a proper navy at the time, making it harder to clamp down on piracy. However, Norderling had on his own initiative established a makeshift fleet.[2] This fleet first saw action in early 1821, when the privateers of José Gervasio Artigas were spotted on Fourchue, and Norderling deployed a schooner. The ship, Victoria, was seized and its crew was captured after a five-hour chase by the local militia.[2][6]

On the 14th of April, Norderling's fleet captured a pirate schooner that had previously been a part of the American Navy.[6] Onboard they found goods stolen from Danish ships, and notified authorities on the Danish colony of Saint Thomas.[2] However, the captured schooner was sold to fund the Swedish fleet.[2][6]

Blockade of Saint-Barthélemy

[edit]On the 8th of May, local authorities took control of an abandoned pirate ship that had washed ashore.[6][2] Pirates had abandoned it after being pursued by a French naval squadron. The same day, French the squadron chased an additional ship into the waters of Saint-Barthelemy. The French attempted to enter Swedish waters but were fired upon by Fort Gustavia, forcing them to leave.[6][2] The pirate ship, while flying an American flag, was in fact a Portuguese vessel that had been captured by Artigas' privateers. Saint-Barthelemy's court decided to return the stolen goods found on the ship to their owners and informed the Portuguese consulate that the goods could be picked up in Porto.[2]

Norderling sought to make this court decision clear to the French fleet. However, the French, angery at having been fired upon, decided to blockade shipping in and from Saint-Barthelemy in the coming few days.[2][6]

The blockade continued until the 31st of May, when the French attacked a British brig that was trying to enter the harbor.[2] The brig received support from Fort Gustavia, which again fired upon the French. The French were temporarily forced back but soon engaged the British again. During the second attack, a Frenchman died due to wounds received from a cannonball fired from the fort, and another lost his arm due to the same shot.[6][2]

The following day, additional French ships arrived. However, the commander of the force had come to make peace, ending the blockade after talks with Norderling.[2][6]

Later the same year, a pirate ship nicknamed "The Revenge", entered the harbor of Saint Barthelemy. A local recognized the ship as a Spanish slave ship. Suspecting that the ship could have been seized via force, Norderling contacted the authorities in Saint-Eustache for confirmation while ordering the ship to stay put.[2][6] However, the ship managed to break out of the harbor despite the harbor captain Wiksell's efforts.[2] The ship's crew proceeded to attack numerous vessels of all nationalities.[5][2] It was later discovered that the ship served under a notable privateer named Dubeoille.[5] Eventually, the pirates returned to Saint Barthelemy and landed on the small island of Fourchue. Due to the strength of the pirates, Norderling was wary of sending the Gustavian militia to capture them and decided to instead hire privateers, who were to accompany Major Hasuum on his way to the island.[6] Hasuum boarded the island's schooner, but it was never put into action as the pirates did not resist being detained.[2]

In December of the same year, the French under Epron again attempted to forcefully enter the Saint Barthelemy harbor but were forced back after receiving fire from Fort Gustavia.[2][6]

In 1822, five pirates were captured and sentenced to death. However, the island lacked the necessary equipment to conduct the execution. Although there were available black slaves who could be ordered to kill the men, it would have been considered taboo for blacks to execute the pirates, who were of European origin. Since there were no willing whites the court ordered that if one of the pirates volunteered to execute the others, he would be allowed to go free.[4]

Aftermath

[edit]The stolen goods aboard the recovered Portuguese ship were all offered back to their owners or sold. All captured pirates were tried in court and some were sold into slavery.[2][6] The French would again make peace with the Swedes, claiming fighting between them had been accidental. Epron and Norderling would thereafter be on good terms and discussed the current state of piracy in the region and what to do about it.[2][6] Piracy would eventually slowly decrease in activity in the Caribbean.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Johan (Jean) Norderling". Riksarkivet.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Les insurgés d'Artigas, des corsaires et des pirates à Saint-Barthelemy en 1821". Saint Barthelemy islander.

- ^ a b "Saint Barthelemy under Sverigetiden". S:t Barthelemysällskapet.

- ^ a b c Thomasson, Fredrik (2022). SVARTA: S:T BARTHELEMY - MÄNNISKO ÖDEN I EN SVENSK KOLONI 1785-1847.

- ^ a b c d e "Den svenska slavhamnen". Dagens Arena.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Johan Norderling's archived reports on the matter". Swedish Caribbean Colonialism - Uppsala University.