Rufous-tailed tyrant

| Rufous-tailed tyrant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Tyrannidae |

| Genus: | Knipolegus |

| Species: | K. poecilurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Knipolegus poecilurus (Sclater, PL, 1862)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

see text | |

The rufous-tailed tyrant (Knipolegus poecilurus) is a species of bird in the family Tyrannidae, the tyrant flycatchers.[2] It is found in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.[3]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant was formally described in 1862 as Empidochanes poecilurus.[4] Later authors placed it genera Cnemotriccus and by itself in Eumyiobius. A 1937 publication placed it in its current genus Knipolegus.[5][6]

The rufous-tailed tyrant has these five subspecies:[2]

- K. p. poecilurus (Sclater, PL, 1862)

- K. p. venezuelanus (Hellmayr, 1927)

- K. p. paraquensis Phelps, WH & Phelps, WH Jr, 1949

- K. p. salvini (Sclater, PL, 1888)

- K. p. peruanus (Berlepsch & Stolzmann, 1896)

However, each subspecies is as variable as the species as a whole and there are no significant genetic differences among them.[7][8]

Description

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant is 14.5 to 15 cm (5.7 to 5.9 in) long and weighs 13 to 15 g (0.46 to 0.53 oz). Adult males of the nominate subspecies K. p. poecilurus have a mostly grayish to brownish gray head and upperparts with a whitish throat. Their wings are dusky with buff edges on the inner remiges and buffy-gray tips on the coverts that show as two wing bars. Their tail is dusky with wide cinnamon edges on the inner webs that are conspicuous in flight. Their underparts are dull buffy gray or cinnamon-buff with a gray wash on the breast. Adult females are very similar to males but slightly browner overall. Both sexes have a red iris, a longish black bill, and black legs and feet. Juveniles have a cinnamon wash, more rufous in the tail than adults, cinnamon wing bars, and a brown iris.[8]

The other subspecies of the rufous-tailed tyrant differ from the nominate and each other thus:[8]

- K. p. salvini: grayer upperparts than nominate, with no wing bars, little rufous in tail, white belly, and rufous vent[9]

- K. p. venezuelanus: intermediate between salvini and nominate

- K. p. paraquensis: smaller and darker than nominate, with no wing markings and no rufous in the tail[9]

- K. p. peruanus: variable but generally darker than the nominate

Distribution and habitat

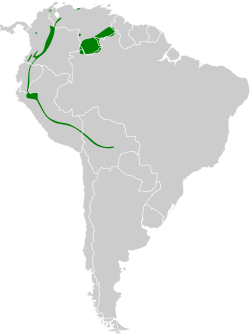

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant has a disjunct distribution. The subspecies are found thus:[8]

- K. p. poecilurus: Colombian Andes and Serranía del Perijá on the Colombia-Venezuela border[9][10]

- K. p. venezuelanus: Venezuela in western states of Táchira and Mérida and separately in the northern Capital District[9]

- K. p. paraquensis: Cerro Sipapo, a tepui in Venezuela's northwestern Amazonas state[9]

- K. p. salvini: tepuis in southern Venezuela's southern Amazonas and southern Bolívar states and immediately adjacent western Guyana and northern Brazil[9][11] The South American Classification Committee of the American Ornithological Society also has records in Suriname.[3]

- K. p. peruanus: eastern slope of the Andes from western Sucumbíos Province of northeastern Ecuador south through Peru into western Santa Cruz Department of Bolivia[12][13]

The rufous-tailed tyrant inhabits a variety of landscapes, most of which are somewhat open. In the Andes these include the edges and clearings of humid montane forest, shrubby areas adjacent to them, and pastures with scattered trees. In most other areas it inhabits these landscapes and also secondary forest. In Peru is also is found in stunted ridgetop forest on nutrient-poor soil. In southern Venezuela it mostly occupies stunted second growth forest on white-sand soils heavy with Melastomataceae. It occurs between 1,500 and 2,500 m (4,900 and 8,200 ft) in elevation in Colombia, mostly between 1,000 and 2,000 m (3,300 and 6,600 ft) in Ecuador, between 900 and 2,300 m (3,000 and 7,500 ft) in Peru, between 500 and 2,500 m (1,600 and 8,200 ft) in Brazil, and up to 1,350 m (4,400 ft) in Venezuela.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

Behavior

[edit]Movement

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant is a year-round resident but is known to make local movements into freshly opened areas such as landslides.[8]

Feeding

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant feeds on insects. It usually forages singly or in pairs and only rarely joins mixed-species feeding flocks. It perches upright, often somewhat hidden in low bushes but also higher on the forest edge and in the open on fence posts. When perched it often lifts and slowly drops its tail. It takes most prey in mid-air with a short sally "(hawking)". It will also drop to the ground to take prey.[8][9][12]

Breeding

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant's breeding season has not been defined but appears to span March to September in Colombia and include August in Ecuador. Two nests are known. They were open cups made from sticks, lined with softer thin fibers, and placed in clumps of grass in cattle pastures. Each contained one egg that was cream with a few red-brown marks. Nothing else is known about the species' breeding biology.[8]

Vocalization

[edit]The rufous-tailed tyrant is not highly vocal.[8] Its call has been described as "a short, metallic trill, tzteeer or triiit",[8][9] "high-pitched, raspy tzreeet notes followed by some jumbled notes",[12] and "a dry, buzzy, descending dzeer [and] a series of high peeps and a sharp, rising tip".[13]

Status

[edit]The IUCN has assessed the rufous-tailed tyrant as being of Least Concern. It has a very large range; its population size is not known and is believed to be stable. No immediate threats have been identified.[1] It is considered "uncommon and local" in Venezuela, local in Brazil and Colombia, "scarce and local" in Ecuador, and "widespread but uncommon" in Peru.[9][10][11][12][13] It is found in protected areas in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2018). "Rufous-tailed Tyrant Knipolegus poecilurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22700244A130206365. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22700244A130206365.en. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (March 2025). "Tyrant flycatchers". IOC World Bird List. v 15.1. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ a b Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 30 March 2025. Species Lists of Birds for South American Countries and Territories. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCCountryLists.htm retrieved 30 March 2025

- ^ Sclater, P. L. (1863). "Characters of Nine New Species of Birds received in collections from Bogota". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (in Latin and English): 112. Retrieved May 6, 2025. The issue is "For the year 1862" and was published in 1863.

- ^ Zimmer, J. T. 1937. Studies of Peruvian birds, No. 27. "Notes on the genera Muscivora, Tyrannus, Empidonomus, and Sirystes, with Further Notes on Knipolegus". American Museum Novitates 962: 1-28.

- ^ Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 30 March 2025. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithological Society. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm retrieved 30 March 2025

- ^ Hosner, P. A. and R. G. Moyle. 2012. A molecular phylogeny of black-tyrants (Tyrannidae: Knipolegus) reveals strong geographic patterns and homoplasy in plumage and display behavior. Auk 129: 156–167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Farnsworth, A. and G. Langham (2020). Rufous-tailed Tyrant (Knipolegus poecilurus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.ruttyr1.01 retrieved May 6, 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hilty, Steven L. (2003). Birds of Venezuela (second ed.). Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 617.

- ^ a b c McMullan, Miles; Donegan, Thomas M.; Quevedo, Alonso (2010). Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Bogotá: Fundación ProAves. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-9827615-0-2.

- ^ a b c van Perlo, Ber (2009). A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 318–319. ISBN 978-0-19-530155-7.

- ^ a b c d e Ridgely, Robert S.; Greenfield, Paul J. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Vol. II. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- ^ a b c d Schulenberg, T.S.; Stotz, D.F.; Lane, D.F.; O'Neill, J.P.; Parker, T.A. III (2010). Birds of Peru. Princeton Field Guides (revised and updated ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 452. ISBN 978-0691130231.