Riverside tyrant

| Riverside tyrant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male K. o. sclateri | |

| |

| Female K. o. sclateri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Tyrannidae |

| Genus: | Knipolegus |

| Species: | K. orenocensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Knipolegus orenocensis Berlepsch, 1884

| |

| |

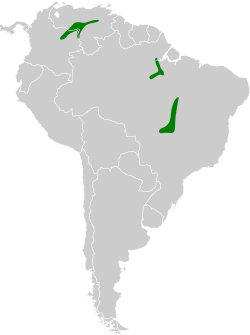

| Ranges of K. o. rrenocensis and K. o. xinguensis; that of K. o. sclateri is not included. See the taxonomy and distribution sections. | |

The riverside tyrant (Knipolegus orenocensis) is a species of bird in the family Tyrannidae, the tyrant flycatchers. It is found in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.[3]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]The riverside tyrant was formally described in 1884 as Cnipolegus orenocensis.[4] The genus' spelling was later changed to the current Knipolegus.

The riverside tyrant's further taxonomy is unsettled. The IOC, the Clements taxonomy, and the South American Classification Committee of the American Ornithological Society assign it these three subspecies:[3][5][6]

However, BirdLife International's Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW) treats K. o. sclateri as a separate species, "Sclater's black-tyrant".[7] Clements supports some level of differentiation by calling it the "riverside tyrant (Sclater's)" within the larger species.[5] Some authors suggest that K. o. xinguensis also deserves species status.[6]

This article follows the one-species, three-subspecies model.

Description

[edit]The riverside tyrant is 15 to 15.5 cm (5.9 to 6.1 in) long and weighs 18 to 21 g (0.63 to 0.74 oz). Adult males of the nominate subspecies K. o. orenocensis are entirely slate gray to blackish gray; their head is the darkest part and has a slight crest. Adult females are a slightly paler slate gray than males and have an olive tinge. Males of subspecies K. o. xinguensis are mostly smoky gray that is darker on the head and paler on the belly. Their throat has very fine darker streaks that are visible only close up. Females are similar to the nominate with a slight buffy wash on the lower flanks and undertail coverts. Juveniles of both subspecies resemble adult females with umber-brown tips on the wing coverts and blurry buff streaks on the underparts. Males of K. o. sclateri are a darker black than the nominate. Females are quite different from the other two. They have sooty gray upperparts with buffy edges on the wing feathers and whitish underparts with heavy darker streaks. Juveniles are brownish gray with a rufous rump, rufous tips on the wing coverts, rufous edges on the flight feathers, and buffish underparts with faint darker streaks. Both sexes of all subspecies have a dark brown iris and black legs and feet. Both sexes of K. o. orenocensis and K. o. xinguensis have a pale blue-gray bill with a black tip. K. o. sclateri has a pale blue-gray bill with a dusky tip.[8]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The riverside tyrant has a disjunct distribution. The subspecies are found thus:[8]

- K. o. orenocensis: from northeastern Meta Department in east-central Colombia east into western and central Venezuela to southeastern Anzoátegui along the lower Apure and upper Orinoco rivers[9][10]

- K. o. xinguensis along the lower Xingu and Araguaia rivers in eastern Amazonian Brazil[11]

- K. o. sclateri along the Amazon tributary rivers Napo, Marañón, and upper Ucayali in northeastern Ecuador, northeastern and eastern Peru, and far southeastern Colombia to the Amazon and along the Madeira and the Amazon main stem in Brazil to the lower Tapajós River in Pará[9][11][12][13]

The riverside tyrant is aptly named. It inhabits somewhat open scrubby areas along rivers and especially on islands; it favors areas in the early stages of succession. In elevation it ranges from near sea level to about 300 m (1,000 ft) in Brazil and Colombia, to about 250 m (800 ft) in Ecuador, and to about 150 m (500 ft) in Venezuela.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

Behavior

[edit]Movement

[edit]The riverside tyrant is primarily a year-round resident but makes local movements in response to changing water levels of the wet and dry seasons.[8]

Feeding

[edit]The riverside tyrant is assumed to feed on insects and other invertebrates, but details are lacking. It usually forages singly or in pairs. In the morning it often perches fairly low in the open but most of the time remains hidden. It takes most prey by dropping to the ground from the perch; less often it takes prey in mid-air ("hawking").[8][10][12]

Breeding

[edit]The riverside tyrant's breeding season has not been defined but includes September in Ecuador, March in Colombia, and April in Venezuela. Males make displays that differ among the subspecies. That of the nominate subspecies is a vertical flight and return to the same perch. K. o. xinguensis has two displays, a short jump from a perch that lands facing 180° from its start and a flight to above the canopy with a folded-wing drop to the same perch. K. o. sclateri flies about 4 m (13 ft) up from a perch and drops to the same one. The species' nest, eggs, incubation period, time to fledging, and details of parental care are not known.[8]

Vocal and non-vocal sounds

[edit]The riverside tyrannulet's song is "a series of musical notes terminating in a hiccup-like gravelly note, pwip, pwip, pwip’PI’tjuk" and its call "a soft liquid pi-weet or pi-piweet".[8] The nominate subspecies calls "a very soft tsik-tsik" before its display flight and "an explosive schue-up!" during it. K. o. xinguensis gives "soft pip pip notes" during its jump display and snaps its wings at the apex of its flight display. K. o. sclateri also makes a wing snap during its display.[8]

Status

[edit]The IUCN follows HBW taxonomy and therefore has separately assessed the riverside tyrant sensu stricto (orenocensis plus xinguensis) and "Sclater's black-tyrant" (sclateri). Both are assessed as being of Least Concern. Both have large ranges. Their population sizes are not known and are believed to be stable. No immediate threats to either have been identified.[1][2] The species is considered "uncommon and local" in Colombia, "rare and local" in Ecuador, "uncommon" in Peru, and "local" in Venezuela.[9][10][12][13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2024). "Riverside Tyrant Knipolegus orenocensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024: e.T103682943A263774214. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T103682943A263774214.en. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2024). "Sclater's Black-tyrant Knipolegus sclateri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024: e.T103682965A263767974. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T103682965A263767974.en. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (March 2025). "Tyrant flycatchers". IOC World Bird List. v 15.1. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ von Berlepsch, Hans (1884). "XLIV.—On a Collection of Bird‐skins from the Orinoco, Venezuela". Ibis (in Latin and English). 2 (4). British Ornithologists’ Union: 433–434. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.1884.tb01178.x. Retrieved May 6, 2025.

- ^ a b Clements, J. F., P.C. Rasmussen, T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht, D. Lepage, A. Spencer, S. M. Billerman, B. L. Sullivan, M. Smith, and C. L. Wood. 2024. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2024. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ retrieved October 23, 2024

- ^ a b Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 30 March 2025. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithological Society. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm retrieved 30 March 2025

- ^ HBW and BirdLife International (2024). Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 9. Available at: https://datazone.birdlife.org/about-our-science/taxonomy retrieved December 23, 2024

- ^ a b c d e f g h Farnsworth, A., J. del Hoyo, N. Collar, G. Langham, and G. M. Kirwan (2022). Riverside Tyrant (Knipolegus orenocensis), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rivtyr2.01.1 retrieved May 6, 2025

- ^ a b c d McMullan, Miles; Donegan, Thomas M.; Quevedo, Alonso (2010). Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Bogotá: Fundación ProAves. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-9827615-0-2.

- ^ a b c d Hilty, Steven L. (2003). Birds of Venezuela (second ed.). Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 617.

- ^ a b c van Perlo, Ber (2009). A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 318–319. ISBN 978-0-19-530155-7.

- ^ a b c d Ridgely, Robert S.; Greenfield, Paul J. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Vol. II. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- ^ a b c Schulenberg, T.S.; Stotz, D.F.; Lane, D.F.; O'Neill, J.P.; Parker, T.A. III (2010). Birds of Peru. Princeton Field Guides (revised and updated ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 452. ISBN 978-0691130231.