Portal:Stars

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and traces of heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime, fusion ceases and its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: NASA's STEREO

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. The Sun has a diameter of about 1,392,000 kilometers (865,000 mi) (about 109 Earths), and by itself accounts for about 99.86% of the Solar System's mass; the remainder consists of the planets (including Earth), asteroids, meteoroids, comets, and dust in orbit. About three-quarters of the Sun's mass consists of hydrogen, while most of the rest is helium. Less than 2% consists of other elements, including iron, oxygen, carbon, neon, and others. The Sun's color is white, although from the surface of the Earth it may appear yellow because of atmospheric scattering. Its stellar classification, based on spectral class, is G2V, and is informally designated a yellow star, because the majority of its radiation is in the yellow-green portion of the visible spectrum. In this spectral class label, G2 indicates its surface temperature of approximately 5,778 K (5,505 °C), and V (Roman five) indicates that the Sun, like most stars, is a main sequence star, and thus generates its energy by nuclear fusion of hydrogen nuclei into helium. Selected article - Photo credit: NASA

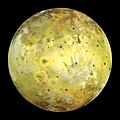

Stars of different mass and age have varying internal structures. Stellar structure models describe the internal structure of a star in detail and make detailed predictions about the luminosity, the color and the future evolution of the star. Different layers of the stars transport heat up and outwards in different ways, primarily convection and radiative transfer, but thermal conduction is important in white dwarfs. The internal structure of a main sequence star depends upon the mass of the star. In solar mass stars (0.3–1.5 solar masses), including the Sun, hydrogen-to-helium fusion occurs primarily via proton-proton chains, which do not establish a steep temperature gradient. Thus, radiation dominates in the inner portion of solar mass stars. The outer portion of solar mass stars is cool enough that hydrogen is neutral and thus opaque to ultraviolet photons, so convection dominates. Therefore, solar mass stars have radiative cores with convective envelopes in the outer portion of the star. In massive stars (greater than about 1.5 solar masses), the core temperature is above about 1.8×107 K, so hydrogen-to-helium fusion occurs primarily via the CNO cycle. In the CNO cycle, the energy generation rate scales as the temperature to the 17th power, whereas the rate scales as the temperature to the 4th power in the proton-proton chains. Due to the strong temperature sensitivity of the CNO cycle, the temperature gradient in the inner portion of the star is steep enough to make the core convective. The simplest commonly used model of stellar structure is the spherically symmetric quasi-static model, which assumes that a star is in a steady state and that it is spherically symmetric. It contains four basic first-order differential equations: two represent how matter and pressure vary with radius; two represent how temperature and luminosity vary with radius. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA

Messier 82 (also known as NGC 3034, Cigar Galaxy or M82) is the prototypenearby starburst galaxy about 12 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major. The starburst galaxy is five times as bright as the whole Milky Way and one hundred times as bright as our galaxy's center. M82 was previously believed to be an irregular galaxy. However, in 2005, two symmetric spiral arms were discovered in the near-infrared (NIR) images of M82, and is now considered a spiral galaxy. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography -Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, FRS (/ˌtʃʌndrəˈʃeɪkɑːr/ ⓘ; Tamil: சுப்பிரமணியன் சந்திரசேகர்; October 19, 1910 – August 21, 1995) was an Indian-American astrophysicist who, with William A. Fowler, won the 1983 Nobel Prize for Physics for key discoveries that led to the currently accepted theory on the later evolutionary stages of massive stars. Chandrasekhar was the nephew of Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930. Chandrasekhar's most notable work was the astrophysical Chandrasekhar limit. The limit describes the maximum mass of a white dwarf star, ~ 1.44 solar mass, or equivalently, the minimum mass above which a star will ultimately collapse into a neutron star or black hole (following a supernova). The limit was first calculated by Chandrasekhar in 1930 during his maiden voyage from India to Cambridge, England, for his graduate studies. In 1999, the NASA named the third of its four "Great Observatories" after Chandrasekhar. The Chandra X-ray Observatory was launched and deployed by Space Shuttle Columbia on July 23, 1999. The Chandrasekhar number, an important dimensionless number of magnetohydrodynamics, is named after him. The asteroid 1958 Chandra is also named after Chandrasekhar. American astronomer Carl Sagan, who studied Mathematics under Chandrasekhar, at the University of Chicago, praised him in the book The Demon-Haunted World: "I discovered what true mathematical elegance is from Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar." From 1952 to 1971 Chandrasekhar also served as the editor of the Astrophysical Journal. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1983 for his studies on the physical processes important to the structure and evolution of stars. Chandrasekhar accepted this honor, but was upset that the citation mentioned only his earliest work, seeing it as a denigration of a lifetime's achievement. He shared it with William A. Fowler.

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |