Necklace of Harmonia

The Necklace of Harmonia, also called the Necklace of Eriphyle, was a fabled object in Greek mythology that, according to legend, brought great misfortune to all of its wearers or owners, who were primarily queens and princesses of the ill-fated House of Thebes.

Origins

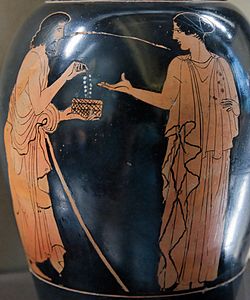

[edit]There are multiple stories concerning the creation of the necklace and origin of its curse. The most common version names Hephaestus, the god of smithing, as its creator. Hephaestus was married to Aphrodite, who regularly had sexual trysts with Ares behind her husband's back. When Hephaestus was informed of his wife's actions by Helios, he was enraged and vowed to curse any children born of the affair. Aphrodite and Ares had multiple children together, including Harmonia, goddess of harmony and concord.[1] Harmonia was betrothed to Cadmus, the legendary founder of Thebes.[2] Upon hearing of the engagement, Hephaestus attended the wedding and gave Harmonia an exquisite necklace (ὅρμος) and peplos (robe) as a wedding gift.[1][3]

In other versions of the myth, the necklace was instead gifted by Athena,[4] Aphrodite,[5] or Cadmus's sister Europa, who had received it as a gift from Zeus.[6] In Hyginus' Fabulae, both Hera and Hephaestus plotted together to curse the gifts, and the peplos was the actual source of the curse ("a robe dipped in crimes").[7]

Description

[edit]No definitive, undisputed description of the necklace exists, however, it was undoubtedly made of gold.[8] Pausanias debates the appearance of the necklace in his Description of Greece,[9] and believed it was likely solid gold, as Homer mentioned in his Odyssey ("who took precious gold as the price of the life of her own lord").[10] However, he states it may have also been a golden necklace inlaid with precious stones, possibly amber.[9]

Other authors claimed the necklace was gold and covered with jewels.[11] Statius described the necklace as being gold with green emeralds, and covered in images of misfortune:[12]

"There forms he a circlet of emeralds glowing with a hidden fire, and adamant stamped with figures of ill omen, and Gorgon eyes, and embers left on the Sicilian anvil from the last shaping of a thunderbolt, and the crests that shine on the heads of green serpents; then the dolorous fruit of the Hesperides and the dread gold of Phrixus' fleece; then divers plagues doth he intertwine, and the king adder snatched from Tisiphone's grisly locks, and the wicked power that commends the girdle; all these he cunningly anoints about with lunar foam, and pours over them the poison of delight."

In his Dionysaica, Nonnus described the necklace as being made of two gold snakes with ruby eyes, their heads joined in the center by a golden eagle with four wings that they held in their mouths. Each of the eagle's wings was covered with a different stone: one was covered in yellow jasper, one in moonstones, one in pearls, and one in agates. The entire necklace was covered with emeralds.[13]

A necklace claimed to be the Necklace of Harmonia was kept in a temple to Adonis and Aphrodite in Amathus. It was gold inlaid with green jewels or stones.[9]

Cursed owners

[edit]Harmonia, Cadmus, and their children

[edit]

Years after their marriage and receiving the necklace, Harmonia and Cadmus were both transformed into serpents, possibly as a consequence of Cadmus slaying Ares's sacred dragon.[14] However, the necklace's role in their misfortune is debatable due to the couple being blessed by the gods, Harmonia being a goddess, and the couple's ascension to Elysium after their transformation.[15][16]

Together, Cadmus and Harmonia had five children: Semele, Ino, Polydorus, Autonoë, and Agave.[17] Each child experienced misfortune. Semele became Zeus's mistress and fell pregnant with Dionysus.[18] However, Zeus's wife Hera discovered the affair; she tricked Semele into asking Zeus to prove his godhood by revealing his true form to her, and she was incinerated.[19] When Dionysus was born, he was placed into the care of Ino, Agave, and Autonoë. However, Hera's jealousy persisted. She struck Ino and her husband Athmas with madness; Athmas hunted down and killed their son Learchus like a deer and Ino boiled their son Melicertes alive before leaping into the ocean with his body, transforming into Leucothea.[1] When Dionysus returned to Thebes as an adult, Autonoë and Agave were swept up in the Bacchic frenzy and festivals he inspired. During the frenzy, the sisters tore Agave's son Pentheus to pieces, and Agave fled Thebes in shame.[16][20] Later, Autonoë's son Actaeon was transformed into a stag and torn to pieces by his own hounds for glimpsing Artemis naked.[21] Both Polydorus and his son, Labdacus, died young.[22][23] In his Library, Apollodorus claimed that Polydorus and Labdacus were torn apart in the Bacchic frenzy alongside Pentheus.[24]

Jocasta, Oedipus, and their children

[edit]The necklace eventually passed to Jocasta, granddaughter of Pentheus. Jocasta unknowingly married her son, Oedipus, and the couple had four children together: Antigone, Eteocles, Polynices and Ismene.[25][26] When Oedipus's identity was discovered, Jocasta committed suicide by hanging and Oedipus gouged his eyes out and exiled himself from Thebes.[27][28][29] Once Oedipus vacated the throne, Eteocles and Polynices became embroiled in a civil war called the Seven Against Thebes for control of the kingdom.[30] Eventually, both brothers killed each other during battle and Antigone was killed in retaliation for her attempts to bury Polynices's body.[31] These events are described in Sophocles' "Three Theban Plays": Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone.

Eriphyle and Alcmaeon

[edit]After Jocasta's death, the necklace and peplos was then inherited by Polynices. Polynices used the necklace to bribe Eriphyle into persuading her husband Amphiaraus to partake in the doomed Seven Against Thebes war effort, aimed at placing Polynices on the Theban throne.[32] She also received the peplos in exchange for persuading her sons Alcmaeon and Amphilochus to join the expedition as well.[33] However, Amphiaraus discovered the plot and instructed his sons that, if he did not survive, they needed to avenge him by killing their mother. When news of Amphiaraus's death reached Alcmaeon, he killed Eriphyle.[34] The necklace and peplos then came into his possession, but he left them behind with his first wife Alphesiboea, daughter of King Phegeus, during his journey to free himself from his mother's vengeful ghost.[35]

Alcmaeon eventually married Callirrhoe, daughter of the river god Achelous. Callirrhoe coveted the necklace and peplos, and demanded that he retrieve them for her.[36] Alcmaeon obliged, and returned to Psophis, where he lied and told Phegeus that he needed the items in order to purify them. Phegeus obliged and handed them over, but instructed his sons Pronous and Agenor to ambush and kill Alcmaeon. When Callirrhoe learned of the murder, she instructed her sons by Alcmaeon, Amphoterus, and Acarnan, to avenge their father. On their journey, they killed Pronous, Agenor, and Phegeus, and retrieved both the necklace and peplos, which they decided to dedicate to the temple of Athena at Delphi.[34]

Phayllus and his mistress

[edit]The necklace stayed at the temple of Athena at Delphi until a Phayllus, a Phocian general in the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC),[37] stole the necklace from the temple to appease his mistress, Ariston's wife, who coveted it.[38] After she had worn it for a time, her son was seized with madness and set fire to the house, and the entire family perished inside.[39][40]

See also

[edit]- Brísingamen, a necklace owned by the North Germanic goddess Freyja

- Heimskringla Chapter 24, Ynglingatal 12, Skald I 28

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Apollodorus, Library, 3.4

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2012-03-29). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP Oxford. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Roman Monica and Luke, p. 201

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 5.48.2

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 5.48.5 & 49.1; Pindar, Pythian Odes 3.167; Statius, Thebaid 2.266; compare Hesiod, Theogony 934; Homeric Hymn to Apollo 195 (cited by Schmitz)

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.4

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 148

- ^ Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists, 6.19

- ^ a b c Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9.41

- ^ Homer, Odyssey, 11.321

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 73

- ^ Statius, Theibad, 2.269

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca, 5.135

- ^ Apollodorus, Library, 3.5.4

- ^ Euripides, Bacchae, 1330

- ^ a b Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 41, at Google Books

- ^ Apollodorus, Library, 3.4.2

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 7.110-8.177 (Dalby 2005, pp. 19–27, 150)

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 167

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 184 Archived 2014-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses, 3.138

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca, 5.190

- ^ Pausanias, 2.6.2 & 9.5.4

- ^ Apollodorus, Library, 3.5.5;

- ^ Euripides, Phoenissae, 55

- ^ Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 66, at Google Books

- ^ Sophocles. Oedipus Rex, 1191–1312.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey, Book XI.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 67

- ^ Hard, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology, pp. 314–317.

- ^ Sophocles, Antigone, 883

- ^ Apollodorus, Library, 3.6.2

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.1.8

- ^ a b Apollodorus, Library, 3.7

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.24.8

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.24.10

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library, 16.37.1

- ^ Parthenius, Erotica Pathemata, 25

- ^ Diodorus Sicilus, Library, 16.64

- ^ Plutarch, De sera numinis vindicta, 8