Mesembryanthemum tortuosum

| Kanna | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Aizoaceae |

| Genus: | Mesembryanthemum |

| Species: | M. tortuosum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mesembryanthemum tortuosum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Mesembryanthemum tortuosum or Sceletium tortuosum, commonly known as kanna, channa, kougoed, or Namaqua skeletonfig, is a succulent plant in the family Aizoaceae, native to the Cape Provinces of South Africa.[1] Traditionally, it has been fermented and chewed as kougoed—an Afrikaans term meaning ‘chewable thing’—by the indigenous Khoisan peoples for its psychoactive effects.[2] The plant contains several active alkaloids, particularly mesembrine.

It has likely been used by South African pastoralists and hunter-gatherers for thousands of years. The first written account of its use dates to 1662, recorded by Jan van Riebeeck. The dried plant was traditionally chewed with the saliva swallowed. It has also been prepared in various forms, including gel caps, teas, tinctures, snuff, and smoked. In traditional medicine, it is primarily used to alleviate stress, depression, pain, and hunger. It is currently classified as a species of least concern, though wild populations face pressure from overharvesting.

Kanna has gained global attention for its stress-relieving and mood-enhancing properties, with modern research focusing on the potential of its bioactive alkaloids to support mental health.[3][4] Preliminary studies using kanna extract Zembrin suggest it may have benefits for mood, anxiety, stress, sleep, and cognitive function.[5] However, it showed no significant effect on reducing anxiety symptoms compared to placebo in a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials.[6] Clinical data are currently insufficient to support the use of kanna for any specific medical indication.[7] Kanna shows potent inhibition of the serotonin transporter and PDE4.[8][9] It promotes monoamine release through vesicular monoamine transporter-2 upregulation, with serotonin reuptake inhibition as a secondary action.[10] It is used as a party drug for its euphoric effects.[5]

Botany

[edit]Sceletium tortuosum is a perennial succulent plant native to South Africa. It features pale-colored sessile flowers about 20–30 mm wide with 4–5 sepals. Its recurved leaves contain distinctive water cells, and the stems become woody as the plant ages.[7]

Raphides have been found in its petals and filaments.[11]

History

[edit]Plants of the genus Sceletium have likely been used for millennia by San and Khoi peoples as masticatories and traditional medicines for thirst, hunger, fatigue, and social and spiritual purposes; this knowledge from oral tradition of how it was used has declined over the past three centuries due to colonization, conflict, and cultural disruption.[12] The first known written account of the plant's use was in 1662 by Jan van Riebeeck. The traditionally prepared dried plant was often chewed and the saliva swallowed, but it has also been made into gel caps, teas and tinctures.[13] It has also been used as a snuff and smoked.[14]

Its name relates to the skeletal appearance of its dried leaves. It was highly valued and traded, sometimes combined with cannabis to enhance effects. Today, it is sold commercially, especially to boost sexual performance.[7]

Uses

[edit]It has been for its mood-altering and medicinal properties by pastoralists and hunter-gatherers since historic times. The earliest recorded use dates back to 1662. It is consumed in various forms—chewed, fermented, made into tinctures, teas, tablets, snuff, or smoked. Traditionally, it serves as a narcotic, sedative, analgesic (relieving mouth pain), and suppresses hunger and thirst during hunting. It has been used to treat toothache, abdominal pain, and digestive issues, especially in pregnant women for constipation, nausea, uterine contractions, and post-birth recovery. An oil made from the plant mixed with sheep’s tail is used to relieve colic in babies.[15]

It is used as a party drug for its euphoric effects.[5] It has been described as producing MDMA-like effects.[16]

It has been studied to alleviate excessive nocturnal barking in dogs or meowing in cats.[12]

Research

[edit]Preliminary studies using kanna extract Zembrin suggest it may have benefits for mood, anxiety, stress, sleep, and cognitive function.[5]

A meta-analysis of four randomized clinical trials involving 117 adults (including one parallel-group and three cross-over studies) found no significant difference in anxiety outcomes between those treated with Sceletium tortuosum and those given a placebo (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.56–1.83; p = 0.98). Based on this evidence, the plant’s effectiveness in reducing anxiety symptoms remains unproven.[6]

Cultivation

[edit]M. tortuosum can be grown from seeds and be propagated from cuttings. Its cultivation and care are similar to cactaceae like Echinopsis. The optimal temperature is at least 16 °C and it does not tolerate frost.[17]

Chemistry

[edit]It contains several alkaloids, with mesembrine being the most active and prominent. Although unfermented preparations contain more alkaloids, traditional fermentation enhances psychoactivity by transforming mesembrine into delta-7 mesembrenone, reducing mesembrine content and harmful oxalates. Fermented extracts exhibit greater bioavailability and efficacy, particularly through mucosal absorption, and show synergistic effects among alkaloids in inhibiting CB1 receptors and acetylcholinesterase—activities stronger than those of mesembrine alone. Seasonal and geographic variations affect alkaloid levels. The psychoactive compounds, including mesembrone, mesembrenol, and turtuosamine, were patented in 1997.[7]

Pharmacology

[edit]Hans Zwicky (1914) was the first to report the presence of alkaloids in Sceletium tortuosum, identifying mesembrine and mesembrenine, though their chemical structures were later corrected. Subsequent research confirmed the structure of mesembrine and noted additional unidentified alkaloids. Studies of fermentation processes revealed that mesembrine transforms into mesembrenone when exposed to sunlight and aqueous conditions, while remaining stable in methanol or darkness.[4]

To date, more than 25 alkaloids from four main structural classes—mesembrine, Sceletium A4, joubertiamine, and tortuosamine—have been identified in Sceletium species, with mesembrine-types predominating. Recent advances include the structural characterization of new alkaloids such as channaine and sceletorines A and B, with evidence indicating sceletorine B may be a biosynthetic precursor to channaine. These discoveries deepen understanding of the chemical diversity and transformation of alkaloids in Sceletium tortuosum, which are key to its pharmacological properties.[4]

M. tortuosum contains about 1–1.5% total alkaloids.[14] A standardised ethanolic extract of dried M. tortuosum had an IC50 for SERT of 4.3 μg/ml and for PDE4 inhibition of 8.5 μg/ml.[18]

Kanna inhibits serotonin reuptake by downregulating the serotonin transporter (SERT) and also promote monoamine release by upregulating VMAT-2. It shows mild inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase-A. The primary mechanism of kanna’s mood effects appears to be monoamine release, with serotonin reuptake inhibition as a secondary action.[10]

It exhibits multiple pharmacological activities, including phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, CB1 receptor blocker, and CYP17A1 inhibitor.[7]

|

|

|

|

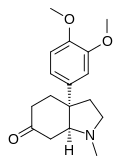

Mesembrine

[edit]Mesembrine is a major alkaloid present in M. tortuosum.[19] There is about 0.3% mesembrine in the roots and 0.86% in the leaves, stems, and flowers of the plant.[14]

Toxicology

[edit]Toxicology data for Sceletium tortuosum in humans is limited. However, animal studies suggest a favorable safety profile. In dogs and cats, daily oral doses of 10 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg respectively showed no toxic effects, with all body systems functioning normally. In Wistar rats, a 90-day oral study using a proprietary extract at doses of 17.85, 35.7, and 71.4 mg/kg revealed no toxic effects, establishing a no-observed-effect level at 71.4 mg/kg. Additional studies administering higher doses—up to 5,000 mg/kg daily for 14 days and up to 600 mg/kg daily for 90 days—also reported no mortality or signs of toxicity. These findings indicate a high margin of safety in animal models.[7]

Traditional and contemporary methods of preparation serve to reduce levels of potentially harmful oxalates found in M. tortuosum.[14] An analysis indicated levels of 3.6–5.1% oxalate, which falls within the median range for crop plants, just like spinach or kale.[14]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]M. tortuosum is found in 50 subpopulations in the Cape provinces from Namaqualand to Montagu and Aberdeen; in karroid habitat.[20]

Conservation status

[edit]M. tortuosum is listed as least concern in the Red List of South African Plants, though it is facing a slow decline in population numbers due to harvesting for medicinal use.[20]

Gallery

[edit]-

Flower

-

Being sold commercially in Cape Town, South Africa. It is ground into a brown powder and ingested orally.

-

Seedling

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Mesembryanthemum tortuosum L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ Viljoen, Alvaro; Chen, Weiyang; Combrinck, Sandra (2023). "Chapter 17 - Mesembryanthemum tortuosum". The South African Herbal Pharmacopoeia: Monographs of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Elsevier. pp. 365–386. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-99794-2.00005-2.

- ^ Manganyi, Madira Coutlyne; Bezuidenhout, Cornelius Carlos; Regnier, Thierry; Ateba, Collins Njie (2021). "A chewable cure "Kanna": Biological and pharmaceutical properties of Sceletium tortuosum". Molecules. 26 (9): 2557. doi:10.3390/molecules26092557. PMC 8124331. PMID 33925290.

- ^ a b c Olatunji, TL; Siebert, F; Adetunji, AE; Harvey, BHH; Gericke, J; Hamman, JH; Van der Kooy, F (6 April 2022). "Sceletium tortuosum: A review on its phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, biological, pre-clinical and clinical activities". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 287: 114711. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114711.

- ^ a b c d Operation Supplement Safety. "Kanna: Uses and Safety in Dietary Supplements." OPSS.org. https://www.opss.org/article/kanna-uses-and-safety-dietary-supplements

- ^ a b Gouhie, F. A., Rodrigues, J. P. A., Vieira, L. F., Cunha, C. L. N., & Yuyama, E. K. (2023). Sceletium tortuosum effects on anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Disorders, 11, 100092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dscb.2023.100092

- ^ a b c d e f "Sceletium tortuosum". Drugs.com. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ^ Harvey, A. L.; Young, L. C.; Viljoen, A. M.; Gericke, N. P. (2011). "Pharmacological Actions of the South African Medicinal and Functional Food Plant Sceletium tortuosum and its Principal Alkaloids" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 137 (3): 1124–1129. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.035. PMID 21798331. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-30.

- ^ Krstenansky, John L. (4 January 2017). "Mesembrine alkaloids: Review of their occurrence, chemistry, and pharmacology". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 195: 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.12.004.

- ^ a b Coetzee, D. D., López, V., & Smith, C. (2016). High-mesembrine Sceletium extract (Trimesemine™) is a monoamine releasing agent, rather than only a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 177, 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.034

- ^ Gulliver 1864, p. 250.

- ^ a b Gericke, N.; Viljoen, A. M. (2008). "Sceletium–A Review Update". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 119 (3): 653–663. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.043. PMID 18761074.

- ^ Manganyi, Madira Coutlyne; Bezuidenhout, Cornelius Carlos; Regnier, Thierry; Ateba, Collins Njie (2021-04-28). "A Chewable Cure "Kanna": Biological and Pharmaceutical Properties of Sceletium tortuosum". Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 26 (9): 2557. doi:10.3390/molecules26092557. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 8124331. PMID 33924742.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, M. T.; Crouch, N. R.; Gericke, N.; Hirst, M. (1996). "Psychoactive Constituents of the Genus Sceletium N.E.Br. and other Mesembryanthemaceae: A Review". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 50 (3): 119–130. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01342-3. PMID 8691846.

- ^ Olatunji, TL; Siebert, F; van der Kooy, F (2021). "Sceletium tortuosum: A review on its phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, biological and clinical activities". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 287: 114937. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114937. PMID 34758918.

- ^ Weiss, Suzannah (March 9, 2020). "This Legal Supplement Made Me Roll Like I’d Taken MDMA". VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/kanna-herbal-legal-mdma/

- ^ "CULTIVATION: How To Grow Healthy Kanna Plants". Kanna Sceletium Tortuosum. 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- ^ Harvey, A. L.; Young, L. C.; Viljoen, A. M.; Gericke, N. P. (2011). "Pharmacological Actions of the South African Medicinal and Functional Food Plant Sceletium tortuosum and its Principal Alkaloids" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 137 (3): 1124–1129. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.035. PMID 21798331. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-30.

- ^ Coetzee, Dirk D.; López, Víctor; Smith, Carine (2016-01-11). "High-mesembrine Sceletium extract (Trimesemine™) is a monoamine releasing agent, rather than only a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 177: 111–116. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.034. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 26615766.

- ^ a b "Threatened Species Programme | SANBI Red List of South African Plants". Retrieved 2024-10-10.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gulliver, George (1864). "Observations on Raphides and other Crystals". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Including Zoology, Botany, and Geology. Third Series. 14: 250–252.

External links

[edit]- Monograph on Sceletium tortuosum

- The past, present and possible future of kanna Video. Talk of Nigel Gericke at Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs. 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- van Wyk, Ben-Erik; van Oudtshoorn, Bosch; Gericke, Nigel (2009). Medicinal Plants of South Africa (2nd ed.). Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-875093-37-3.