Church of the East in India

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

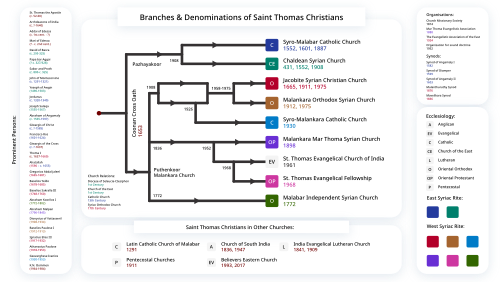

According to apocryphal records, Christianity in India and in Pakistan (included prior to the Partition) commenced in 52 AD,[1] with the arrival of Thomas the Apostle in Cranganore (Kodungaloor). Subsequently, the Christians of the Malabar region, known as St Thomas Christians established close ties with the Levantine Christians of the Near East. They eventually coalesced into the Church of the East led by the Catholicos-Patriarch of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

The Church of the East was often separated from the other ancient churches due to its location in the Parthian Empire, an ancient rival of the (Byzantine) Greek and (Latin) Roman Empires. When Archbishop Nestorius of Constantinople was declared a heretic by the Council of Ephesus, the Church of the East refused to acknowledge his deposition because he held the same christological position. Later, the "Anaphora of Mar Nestorius" came to be used by Church of the East, which for this reason has been pejoratively labelled the "Nestorian Church" by its theological opponents.

When the Portuguese Inquisition in Goa and Bombay-Bassein was established in the 16th century, they opposed the East Syriac rite of Christian worship in what was Portuguese Cochin. After the schism of 1552, a section of the Church of the East became Catholic (modern-day Chaldean Catholic Church), both the traditional (Nestorian) and Chaldean patriarchates intermittently attempted to regain their following in the Indian subcontinent by sending their prelate to the Malabarese Christians. Occasionally the Vatican supported the claim of the bishop from the Chaldean Church of Ctesiphon. But the Synod of Diamper in 1599, overseen by Aleixo de Menezes, the Portugal-backed-Archbishop of Goa, replaced the East Syriac bishop of St Thomas Christians and placed them under the Portuguese Padroado backed bishop.[2] After that any attempts of Thomas Christians to contact bishops—even Chaldian Catholic ones—in the Middle East were foiled.[3]

Mar John, Metropolitan of India (1122 AD)

[edit]

In 1122, Mar John, Metropolitan-designate of India, with his suffragans went to Constantinople, thence to Rome, and received the pallium from Pope Callixtus II.[4] He related to the Pope and the cardinals the miracles that were wrought at the tomb of St. Thomas at Mylapore.[5] These visits, apparently from the Saint Thomas Christians of India, cannot be confirmed, as evidence of both is only available from secondary sources.[6][7][8] Later, a letter surfaced during the 1160s claiming to be from Prester John. There were over one hundred different versions of the letter published over the next few centuries. Most often, the letter was addressed to Emanuel I, the Byzantine Emperor of Rome, though some were addressed to the Pope or the King of France.

Historian Meir Bar-Ilan notes that a 20th-century collection of Hebrew Prester John Letters, edited by Ullendorff and Beckingham (1982) "present[s] a Latin text with its Hebrew translation (and an English text where the Latin is missing) as follows":[9]

Praete janni invenitur ascendendo in Kalicut in arida ... [In English: 'It is found on the banks of the Janni rising in Calicut in the dry season ...] This is true proof and well-known knowledge about the Jews who are found there near Prester John.

— The Hebrew Letters of Prester John. 1982. pp. 32–33

Bar-Ilan concludes that evidence from the Hebrew Letters "shows that Prester John lived in India; or to be more precise, in Malabar (southern India)".[9]: 292

Mar Ya'qob Metropolitan of India and Patriarch Yahballaha III

[edit]

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Indian church was again dependent upon the Church of the East. The dating formula in the colophon to a manuscript copied in June 1301 in the church of Mar Quriaqos in Cranganore mentions Patriarch Yahballaha III (whom it calls Yahballaha V) and Metropolitan Yaqob of India. Cranganore, described in this manuscript as "the royal city", was doubtless the metropolitan seat of India at this time.[10]

In the 1320s, the anonymous biographer of the patriarch Yahballaha III and his friend Rabban Bar Sauma praised the achievement of the Church of the East in converting "the Indians, Chinese and Turks".[11] India was listed as one of the Church of the East's "provinces of the exterior" by the historian Din ‘Amr in 1348.[12][incomplete short citation]

Yahballaha maintained contacts with the Byzantine Empire and with Latin Christendom. In 1287, when Abaqa Khan's son and successor Arghun Khan sought an ambassador for an important mission to Europe, Yaballaha recommended his former teacher Rabban Bar Sauma, who held the position of Visitor-general. Arghun agreed, and Bar Sauma made a historic journey through Europe; meeting with the Pope and many monarchs; and bringing gifts, letters, and European ambassadors with him on his return. Via Rabban Sauma, Yahballaha received a ring from the Pope's finger, and a papal bull which recognized Yahballaha as the patriarch of all the eastern Christians.[13]

In May 1304, Yahballaha made profession of the Catholic faith in a letter addressed to Pope Benedict XI. But a union with Rome was blocked by his Nestorian bishops.

Udayamperoor (known as Diamper in Portuguese), the capital of this kingdom, was the venue of the famous Synod of Diamper of 1599. It was held in the All Saints Church there. The venue was apparently chosen on account of the place having been the capital of a Christian principality.[14]

Synod of Diamper and suppression of East Syriac jurisdiction in India

[edit]In 1552, there was a schism in the Church of the East and a faction led by Mar Yohannan Sulaqa declared allegiance to Rome. When, on 6 April 1553, Pope Julius III confirmed Yohannan Sulaqa as Chaldean Patriarch, the Pope said that the discipline and liturgy of the Chaldeans had already been approved by his predecessors, Nicholas I (858–867), Leo X (1513–1521), and Clement VII (1523–1534).[citation needed] Thus, parallel to the "traditionalist" (often referred as Nestorian) Patriarchate, the "Chaldean" Patriarchate in communion with Rome came into existence and both traditionalist and Chaldean factions began sending their own bishops to Malabar.

When the Portuguese arrived in Malabar, they assumed that the four bishops present were Nestorian. Their report of 1504, addressed to the Chaldean Patriarch, their being startled by the absence of images and by the use of leavened bread; but this was in accordance with Chaldean usage. The Christians paid the expenses of the Papal delegate Marignoli.[15][clarification needed]

The Synod of Diamper of 1599 marked the formal subjugation of the Malabar Syriac Christian community to the Latin Church. It implemented various liturgical and structural reforms in the Indian Church. The diocese of Angamaly, which was now formally placed under the Portuguese Padroado and made suffragan to the archdiocese of Goa. The east syriac bishop was then removed from jurisdiction in India and replaced by a Latin bishop; the East Syriac liturgy of Addai and Mari was “purified from error”; and Latin vestments, rituals, and customs were introduced to replace the ancient traditions.[2]

Accounts of foreign missionaries

[edit]

Francis Xavier wrote a letter dated 26 January 1549, from Cochin to king John III of Portugal, in which he declared that:

... a bishop of Armenia (Mesopotamia) by the name of Jacob Abuna has been serving God and Your Highness in these regions for forty-five years. He is a very old, virtuous, and saintly man, and, at the same time, one who has been neglected by Your Highness and by almost all of those who are in India. God is granting him his reward, since he desires to assist Him by himself, without employing us as a means to console his servants. He is being helped here solely by the priests of St. Francis. Y. H. should write a very affectionate letter to him, and one of its paragraphs should include an order recommending him to the governors, to the veadores da fazenda, and to the captains of Cochin so that he may receive the honour and respect which he deserves when he comes to them with a request on behalf of the Christians of St. Thomas. Your Highness should write to him and earnestly entreat him to undertake the charge of recommending you to God, since YH. has a greater need of being supported by the prayers of the bishop than the bishop has need of the temporal assistance of Y.H. He has endured much in his work with the Christians of St Thomas.[16][incomplete short citation][17]

In that same year, Francis Xavier also wrote to his Jesuit colleague and Provincial of Portugal, Fr. Simon Rodrigues, giving him the following description:[16][17]

Fifteen thousand paces from Cochin there is a fortress owned by the king with the name of Cranganore. It has a beautiful college, built by Frey [Wente], a companion of the bishop, in which there are easily a hundred students, sons of native Christians, who are named after St. Thomas. There are sixty villages of these Thomas Christians around this fortress, and the students for the college as I have said, are obtained from them. There are two churches in Cranganore, one of St. Thomas, which is highly revered by the Thomas Christians.

This attitude of St. Francis Xavier, and of the Franciscans before him, does not reflect any of the animosity and intolerance that kept creeping in with the spread of the Tridentine spirit of the Counter-Reformation, which tended to foster a uniformity of belief and practice. It is possible to follow the lines of argument of young Portuguese historians, such as Joéo Paulo Oliveira e Cosca, yet such arguments seem to discount the Portuguese cultural nationalism in their colonial expansion and the treatment of the natives. Documents recently found in the Portuguese national archives help to confirm a greater openness or pragmatism in the first half of the 16th century.[17][18][clarification needed]

Malankara-Persian ecclesiastical relations

[edit]Several historical evidences shed light on a significant Malankara–Persian ecclesiastical relationship that spanned centuries. While an ecclesiastical relationship existed between the Saint Thomas Christians of India

and the Church in Sassanid Empire (Church of the East) in the earlier centuries, closer ecclesiastical ties developed as early as seventh century, when India became an ecclesiastical province of the Church of the East, albeit restricted to matters of purely ecclesiastical nature such as ordination of priests, and not involved in matters of temporal administration. This relationship endured until the Portuguese protectorate of Cochin of Malabar came to be in 16th century, and the Portuguese discovery of a sea route to India.[19] The Christians who came under the two ancient yet distinct lineages of Malankara and Persia had one factor in common: their Saint Thomas heritage. The Church of the East shared communion with the Great Church (Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy) until the Council of Ephesus in the 5th century, separating primarily over differences in Christology.

The Saint Thomas Christians of India came in contact with Portuguese Latin Catholic missionaries only in the 16th century. Later, after the Oath of Koonan Cross (meaning "leaning cross") in 1653, the Saint Thomas Christians came in touch with the Syriac Orthodox Church.[19]

Though claims have been made that the Saint Thomas Christians of Malankara had close interactions with the Roman Catholic Church and Syriac Orthodox Church before the 16th century, these assertions lack proof.[20][21][22]

Early references

[edit]

The celebrated Church historian Eusebius has mentioned in his work that the Alexandrian scholar Pantenus[23] had seen Christians during his visit to India between 180 A. D. and 190 A. D. This account of Eusebius has later been quoted by several historians. According to Eusebius, Pantenus saw people reading the Gospel according to Mathew in Hebrew. Based on this reference by Eusebius, Jerome has recorded the existence of Christians in India during the early centuries of Christian Era. In addition to this, Jerome mentions that Pantenus held debates with Brahmins and philosophers in India.[24]

The evangelization of India is mentioned in a number of ancient works, including the book Acts of Judas Thomas written in Edessa around 180 A. D. in Syriac language, and Didascalia (meaning teachings of the Apostles) written around 250 A. D. Historians have often remarked that the Persians might have received this tradition about the Church in India from India itself.

The Chronicle of Seert is a historical document compiled in the Middle Ages. In this Chronicle, the Church in India is mentioned along with the history of Persian Church and the Patriarchs (Catholicoi) of Babylon. It also states that during the reigns of Shahlufa and Papa bar Aggai as the heads of Persian Church, the Persian bishop David of Basra preached the Gospel in India.[25] Some historians' records regarding the participation of Bishop John representing Persia and India as the Bishop of all of Persia and Greater India in the first Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 A. D. remains a matter of contention among historians.

Ishodad was a famous Bible scholar who lived in Persia in the 5th century. In his commentary on the Epistle to Romans, a note is scribbled in the margin that may be translated as: This article is translated by Mar Komai with the help of Daniel, an Indian priest, from Greek to Syriac. This statement reveals the connection between the Indian priest Daniel and the Persian bishop Mar Komai.[26][27][28]

Persian Immigration

[edit]The two instances of immigration from Persia to Malankara (India) substantiate the Malankara-Persia connection. The first of these, which occurred in the 4th century, was led by a merchant named Thoma (fondly referred to as Knai Thoma or Knai Thomman by the Christians of Malankara, meaning Thomas of Cana), while the second immigration was led by two Persian bishops, Prod and Sappor in the 9th century.

There exists the strong traditional belief that Thomas of Cana, accompanied by a Persian bishop and seventy two families, reached the ancient port of Kodungallur in India. The history of Knanaya in Malankara is inseparably related to this immigration.

In 825 A. D., a group of Persians under the leadership of two Persian bishops Prod (or Proth, also known as Aphroth) and Sappor (also known as Sabrisho)reached Kerala and resided in Quilon. They received great honors from the native ruler known as Sthanu Ravi Varma who bestowed 72 titles and special rights and concessions on them. The king believed that the immigrants who were merchants by profession would boost the economy. Their Church in Quilon was known as Thareesa Pally and the titles were engraved on metal plates known as Thareesa Pally Chepped.

Indian Church records

[edit]The oldest known Syriac manuscript copied in India in 1301 AD at Cranganore (1612 AG) at the Church dedicated to Mar Quriaqos and currently kept at the Vatican Library (MS Vatican Syriac 22) was written in Estrangela script by a very young deacon named Zakharya bar Joseph bar Zakharya, who was just 14 at the time of writing.[19] In that lectionary, it is stated that it was compiled during the time of Church of the East Patriarch Yahballaha III and Mar Yakob, the Metropolitan on the throne of St. Thomas in India at Kodungallur. The Church fathers Nestorius, Theodore and Deodore, who are venerated in the Church of the East, are also mentioned in this lectionary.[29][30] Johannes P. M. van der Ploeg comments that the author refers to Yahballaha III as 'the fifth'.

This holy book has been written in the royal and well known and famous town Shengala in the land of India, in the holy church dedicated to the glorious martyr Mar Quriaqos .... whilst our blessed and holy father Mar Yahballaha the fifth, the Turk, qatoliqa Patriakis of the East, the head of all the countries, was great governor, holding the offices of the Catholic Church of East, the shining lamp which illuminates its regions, the head of the pastors and Pontiff of the pontiffs, Head of great high priests, Father of the fathers.. The Lord may make long his life and protect his days in order that he may govern her, a long time, for her glory and for the exaltation of her sons. Amen.

Persian Bishops in Malankara

[edit]While some Persian Bishops who traveled to Malankara belonged to different groups of immigrants fleeing persecution, others visited Malankara to provide spiritual administration to the Malankara Nasranis. Niranam Grandhavari[31] gives a list (incomplete) of Persian bishops and the year of their visits to Malankara.

- Mar Joseph of Uraha (Edessa) (345 A. D.)

- Mar Sabor and Mar Proth (825 A. D.)[19][32][33]

- Mar Yohannan (988 A.D.)

- Mar Joseph (1056 A.D.)

- Mar Yacob (1122 A. D.)

- Mar Joseph (1221 A.D.)

- Mar David (1285 A.D.)

- Mar Yabaloha (1407 A.D.)

- Mar Thoma and Mar Yohannan (1490 A.D.)[34][35][36][37][38][39]

- Mar Yahballaha, Mar Dinkha and Mar Yacob (1504 A.D.)[19][40][41][42]

- Mar Abraham (1565 A. D.)[19]

It is worth noting that the Chaldean Catholic Church was originated only in 1552 AD following a schism in the Church of the East. This invalidates recent claims that the Persian Bishops were sent by the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch, which is impossible considering that almost all of them visited Malankara before the origin of Chaldean Catholic Church.

Persian Church Records

[edit]Several evidences are available from the historical records of Persian Church and letters of Persian bishops which corroborate the Malankara-Persian relation.

In the 5th century, Mar Mana, the Persian bishop of Rev Ardashir recorded that while sending his theological works and the works and translations of other Persian bishops to various places, they were sent to India as well.

During the reign of Persian emperor Khosrau II in the 6th century, bishop Marutha reached Persia as the delegate of the Roman Emperor and visited the Persian Patriarch Sabrisho I (594–604). It is recorded that during this visit, the Patriarch presented bishop Marutho with fragrant spices and other special gifts which he had received from India.

Two letters from Persian Patriarch Ishoyahb III to the Metropolitan bishop of Fars between 650 and 660 A. D. show that the Indian Christians were under the jurisdiction of the Persian Patriarchate.[43] In the 7th century, Fars was an eparchy (ecclesiastical province) in the Persian Church with Rev Ardashir as its capital. At that time, Metropolitan bishop Simon of Rev Ardashir was in charge of the affairs of the Church of India. However, a situation arose in which the bishop became hostile to the Patriarch, resulting in excommunication. In his letter, the Patriarch reprimands the bishop and complains that because of the opposition of the bishop, it was impossible to tend to the spiritual needs of the faithful in India. The Patriarch adds that the Indians were cut off from the Patriarchate and the annual offertory given to the Patriarch by the Indians was no longer given. Following this, Patriarch Ishoyahb III issued an encyclical releasing the Church of India from the jurisdiction of Fars eparchy and appointed a Metropolitan Bishop for India. According to the canons of Persian Church in the medieval centuries, the bishop of India came tenth in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, followed by the bishop of China. The title of the Metropolitan bishop of India was the Metropolitan and Gate of all India.

Also during the reign of Patriarch Timothy the Great (780–823), the Patriarch released the Church of India from the authority of the bishop of Fars, placing it under his direct jurisdiction. Historians refer to two letters written by Patriarch Timothy with regard to the Church of India. The first letter contains guidelines for the election of Metropolitans. The letter demands that the acknowledgement of the Patriarch must be obtained after the people selected bishops based on the guidelines set by the Patriarch, before requesting the acknowledgement of the Emperor. In the second letter addressed to the Archdeacon of Malankara, the Patriarch mentions some violations of canon in the Church of India. The Patriarch also demands that bishops should abstain from entering wedlock and consuming meat.

While writing about the journeys of Nestorian missionaries during his reign, Timothy I himself says (in Letter 13) that a number of monks go across the sea to India with nothing but a staff and a beggar's bag.

In the Persian Church, the bishops were supposed to report to the Patriarch every year. However, Patriarch Theodosius (853–858) suggested that the bishops of distant places like India and China need to report only once every six years, owing to the great distance.

In 1129, in response to the request of the Church of India, the Persian Patriarch Eliya II sent bishop Mar Yohannan to Malabar (Kerala, India). Mar Yohannan reached Kodungallur and gave the Church spiritual leadership from there. In 1490, a three-member delegation of the Christians of Malankara left for Baghdad with a petition to the Patriarch requesting him to appoint a Metropolitan Bishop for them. One of them perished on the way. The remaining two, named George and Joseph, were ordained to priesthood by Patriarch Shemʿon IV Basidi. The Patriarch selected two monks from the monastery of Mar Augen and consecrated them as bishops Mar Thoma and Mar John. These bishops accompanied the two priests on their return to India. Bishop Mar John died shortly after. Later, Mar Thoma and the priest Joseph returned to Baghdad.

Patriarch Eliya V, who ascended the throne in 1502, sent three bishops, namely Mar Yabalaha, Mar Yakob and Mar Denaha to Malankara. By the time they reached Malankara, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama had already set foot in Kerala. The three bishops were detained by the Portuguese. Few years later, Patriarch Abdisho IV Maron sent bishop Abraham to Malankara. Mar Abraham was also imprisoned by the Portuguese. As a result of the injuries suffered at the hands of the Portuguese, Mar Abraham died in 1597. Thus, the authority of Persian bishops in Malankara reached its termination.

Testimonials of travelers

[edit]The 6th century Gallo-Roman historian Gregory of Tours has recorded the trips of Theodore, a Persian monk, to India on several occasions where the latter visited the tomb of Apostle St. Thomas and an adjoining monastery.

Near the end of the 6th century, the Persian scholar Bodha has recorded his visit to India where he held discussions with Indian religious scholars in Sanskrit language.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, the Alexandrian traveler visited India during 520–525. Later, he wrote a book titled Christian Topography in which he mentions the Churches of Persia, India, Ceylon etc. Cosmas states the existence of Christians in Malabar, where pepper grows. Cosmas also records that there were Christians at Kalyana (Kalyan in Mumbai, India) with a bishop appointed from Persia. The traveler tries to emphasize the spread of Christianity in all these places.[44]

Marco Polo, who visited Kerala in 1295 has recorded that he saw Nestorian Christians there.

A lectionary compiled in 1301 in Syriac language at Kodungallur in Kerala is kept in the collection of Syriac manuscripts in the Vatican Library. In that lectionary, it is stated that it was compiled during the time of Church of the East Patriarch Yahballaha III and Mar Yakob, the Metropolitan on the throne of St. Thomas in India at Kodungallur. The Church fathers Nestorius, Theodore and Deodore, who are venerated in the Church of the East, are also mentioned in this lectionary.[45][30]

In an Arabic document written near the end of 14th century titled Churches and Monasteries in Egypt and its surroundings, it is mentioned that pilgrims visit the tomb of Apostle St. Thomas in Mylapore, India. In the same document, it is stated that a Church in the name of the Mother of God exists in Kullam (modern day Kollam in Kerala) and that the Christians there are pro-Nestorians.

Persian Stone Crosses in Malankara

[edit]The Persian stone crosses in Malankara are eternal witnesses to Malankara-Persia connection.[46][44] At present, five such Persian crosses exist, two at Kottayam (Knanite) Knanaya Jacobite Valiya pally (meaning greater church), one each at Mylapore St. Thomas Mount, Kadamattom St. George Orthodox Church[47] and Muttuchira Catholic Church. These crosses are chiseled on stone and embedded in the walls of these churches. Some writings in ancient Persian language are also engraved near these crosses. The central panel, which contains the figure of the cross with its symbolic ornaments, is enclosed by an arch that has an inscription in the Pahlavi script of Sassanian Persia.[48]

Decisions of the Synod of Diamper

[edit]The infamous Synod of Diamper was a calculated move towards separating the Malankara Church from Persian connection and bringing it under the Pope of Rome. This was the aim of Portuguese missionaries since the beginning of their missionary works in India. Their efforts culminated in the Synod of Diamper in 1599. Aleixo de Menezes, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Goa, who visited the churches of Malankara prior to convening the synod, had expressed his indignation over the prayer for the Patriarch of Persia amid the Divine Liturgy in those churches. He strictly admonished that the pope was the general primate (Catholicos) of the Church and in his stead, no one else should be prayed for. Several canons of the synod, including canons 12, 17, 19 etc. were solely aimed at obstructing and obliterating Malankara-Persian relation and establishing a relationship with Rome instead.[49][30]: 45

In spite of almost sixteen centuries of Persian connection, a majority of the Christians of Malankara became associated with the Roman Catholic Church and Western Syriac Church of Antioch (Syriac Orthodox). At present, only a very small minority of Christians in Malankara (numbering around 50,000) are in direct connection with the Assyrian Church of the East.[50]

Liturgical language

[edit]During the early centuries of Christian Era, the population to the east of Tigris–Euphrates river system was under Persian rule, while the population to its west was under Roman rule. The Syrian people spread over the two empires used the Syriac language independently by developing distinct transformations from basic Esṭrangēlā. The form of Syriac which was developed in Persia resembled Esṭrangēlā more closely, and is referred to as Eastern Syriac, Chaldean Syriac or Nestorian Syriac. Until the 17th century, the Church of India used this dialect. Following the Synod of Diamper in 1599 and the Oath of Coonan Cross in 1653, they came in direct contact with the West Syriac tradition and hence with the West Syriac dialect of the language.[51] Until then, the Liturgy of Nestorius, who is considered a saint by the Chaldean Church and anathematized by the Western Syriac tradition, was popular in Malankara. Gregorios Abdal Jaleel, who was the first West Syrian bishop to visit Malankara, faced severe opposition from the people of Malankara for following West Syrian liturgy, and was asked to follow the East Syrian liturgy, which the people referred to as old liturgy.[52][53]

Since the 17th century, efforts were made by the visiting bishops of West Syriac tradition to establish the use of western dialect in liturgy in Malankara. Written in a more roundly form, this dialect is known as Western Syriac, Maronite Syriac or Jacobite Syriac. As both these forms are indistinguishable in terms of grammar and meaning, they differ only in the shape of letters and pronunciation. Even though the Western Syriac was introduced in the Malankara Church in the 17th century, its use was still greatly eclipsed by the use of Eastern Syriac until the 19th century, as shown by the pronunciations in the Eastern Syriac way which have transcended into the daily usage and liturgical translations of the Christians of Malankara. This is exemplified by the pronunciation of words like Sleeba, Kablana, Qurbana, Kasa, Thablaitha etc. (instead of Sleebo, Kablono, Qurbono, Kaso, Thablaitho as in the Western dialect) which has remained unchanged through the centuries. Even the letters written by the primate of Malankara Church, Malankara Metropolitan Mar Dionysius, the Great (+1808) were in Eastern Syriac.[24] As the attempts by Western Syriac visiting bishops to get Western Syriac liturgy adopted by the Malankara Church continued to face opposition from Malankara, a middle ground was reached in 1789 by the Malankara Palliyogam (assembly of parish representatives) held at Mavelikkara Puthiyakavu church and presided by Mar Dionysius, the Great. The decision was documented in the historical document Puthiyacavu Padiyola which stated that the prayers of canonical hours, ordinations and Holy Qurbana must be done in the new liturgical rite (Western Syriac), while weddings and baptisms must continue following the old liturgical rite (Eastern Syriac).[54][55] Two decades later, the transition to Western Syriac Liturgy was fully implemented by the Malankara Palliyogam of 1809 through the declaration Kandanad Padiyola which stated that all prayers and sacraments must follow the Western Syriac liturgical rites.[56][57]

See also

[edit]- Gondophares

- Chaldean Syrian Church

- St Gaspar

- India (East Syriac ecclesiastical province)

- Malankara-Persian ecclesiastical relations

- Assyrian Church of the East in India

- Near East

Notes

[edit]- ^ Curtin, D. P.; Nath, Nithul. (May 2017). The Ramban Pattu. Dalcassian Publishing Company. ISBN 9781087913766.

- ^ a b "Synod of Diamper". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

The local patriarch—representing the Assyrian Church of the East, to which ancient Christians in India had looked for ecclesiastical authority—was then removed from jurisdiction in India and replaced by a Portuguese bishop; the East Syrian liturgy of Addai and Mari was "purified from error"; and Latin vestments, rituals, and customs were introduced to replace the ancient traditions.

- ^ Brock, Sebastian P. (2011). "Thomas Christians". In Sebastian P. Brock; Aaron M. Butts; George A. Kiraz; Lucas Van Rompay (eds.). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

The destruction of all Syriac books considered heretical at the Synod of Diamper (1599) and the Romanization of the rite (though Syriac was still allowed) witness to the domineering character of the European hierarchy in India. Any attempts to contact bishops — even Chald. Catholic ones — in the Middle East were foiled.

- ^ The realm of Prester John, Silverberg, pp. 29–34.

- ^ Raulin, op. cit., pp. 435-436. Counto. Asia Lisbonne, 1788, Dec. XII, p. 288.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (1997). Otto of Freising: The Legend of Prester John Archived 13 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Retrieved 20 June 2005.

- ^ Silverberg, pp. 3–7

- ^ Bowden, p. 177

- ^ a b Bar-Ilan, Meir (January 1995). "Prester John: Fiction and history". History of European Ideas. 20 (1–3): 291–298. doi:10.1016/0191-6599(95)92954-S. Citing:

- "The Hebrew letters of Prester John were printed in Constantinople 1519, and later in":

- Neubauer, A. (1888). "Collections on the Lost Ten Tribes and the Children of Moses" Qobes al Yad, vol. IX, pp. 1–74; (in Hebrew); and

- Ullendorff, E.; Beckingham, C. F. (1982). The Hebrew Letters of Prester John. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- "The Hebrew letters of Prester John were printed in Constantinople 1519, and later in":

- ^ MS Vat Syr 22; Wilmshurst, EOCE, 343 and 391

- ^ Wallis Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, 122–123

- ^ Wilmshurst, EOCE, 343

- ^ Phillips, p. 123

- ^ "History of Indian Churches". Synod of Diamper (in Malayalam). 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Father Nidhiry: A History of His Times by Prof. Abraham Nidhiry

- ^ a b Costellioe, Letters, 232–246

- ^ a b c "Christen und Gewürze" : Konfrontation und Interaktion kolonialer und indigener Christentumsvarianten Klaus Koschorke (Hg.) (in German, English, and Spanish), 1998. pp. 31–32

- ^ Arquivio Nacional torre do Tombo Lisbo:Nucleo Antigo N 875 contains a summary of letters from india written in 1525 and also the kings replay to it :Cf.OLIVERIA E COSTA, Portuguese, Apendice Documental 170-178

- ^ a b c d e f Brock (2011a).

- ^ Cardinal Tisserant, Eugene (1957). Eastern Christianity in India. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 17.

- ^ Malancharuvil, Cyril (1973). The Syro Malankara Church. p. 7.

- ^ Rev. Dr. Varghese, T. I. മലങ്കര അന്ത്യോഖ്യൻ ബന്ധം പത്തൊമ്പതാം നൂറ്റാണ്ടിൻ്റെ സൃഷ്ടി [Malankara-Antioch Relation a Nineteenth Century Creation] (in Malayalam).

- ^ nl:Pantenus

- ^ a b John, Fr. M. O. (December 2013). "പോർട്ടുഗീസ് വരവിനു മുമ്പുള്ള മലങ്കര സഭയുടെ വിദേശ ബന്ധം" [Foreign Relationship of the Malankara Church before the Arrival of the Portuguese]. Basil Pathrika (in Malayalam). Pathanamthitta: Thumpamon Diocese.

- ^ "St. Gregorios Malankara (Indian) Orthodox Church of Washington, DC : Indian Orthodox Calendar". Stgregorioschurchdc.org. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Paul IAS, D. Babu (1986). The Syrian Orthodox Christians of St. Thomas. Cochin: Swift Offset Printers. p. 11.

- ^ Sugirtharajah, R. S. (2001). The Bible and the Third World: Precolonial, Colonial and Postcolonial Encounters. Cambridge: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. p. 18. ISBN 978-0521005241.

- ^ Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian Missionary Enterprise: The Story of a Church on Fire. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 88. ISBN 9789333452519.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Dr. Mar Gregorios, Paulos. വത്തിക്കാൻ ലൈബ്രറിയിൽ നിന്നും ഒരു പുതിയ രേഖ [Vatican Libraryil ninnum oru puthiya rekha] (PDF) (in Malayalam). India: Kottayam.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Dr. M. Kurian. കാതോലിക്ക എന്ന് ചൊല്ലി വാഴ്ത്തി ഞായം [Catholica Ennucholly Vazhthy Njayam - History & Relevance of the Catholicate] (PDF) (in Malayalam). India: Sophia Books, Kottayam.

- ^ Niranam Granthavari (Record of History written during 1770–1830). Editor Paul Manalil, M.O.C.Publications, Catholicate Aramana, Kottayam. 2002.

- ^ Kerala Charithram P.59 Sridhara Menon

- ^ V. Nagam Aiya (1906), Travancore State Manual, page 244

- ^ Mingana 1926, p. 468-470.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 16-18.

- ^ Mundadan 1967, p. 56-58.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 20, 347, 398.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 106-111.

- ^ Neill (2004), p. 193-195.

- ^ Rev. H Hosten, St Thomas Christians of Malabar, Kerala Society papers, Series 5, 1929,

- ^ "Christen und Gewürze" : Konfrontation und Interaktion kolonialer und indigener Christentumsvarianten Klaus Koschorke (Hg.)Book in German, English, Spanish, 1998 Page 31,32

- ^ Neill (2004), p. 194.

- ^ "Chronicles of Malabar: Influence of Persian Christianity on Malabar(500–850)". Chroniclesofmalabar.blogspot.com. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ a b Mihindukulasuriya, Prabo. "Persian Christians in the Anuradhapura Period". Academia.edu. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Dr. Mar Gregorios, Paulos. വത്തിക്കാൻ ലൈബ്രറിയിൽ നിന്നും ഒരു പുതിയ രേഖ [Vatican Libraryil ninnum oru puthiya rekha] (PDF) (in Malayalam). India: Kottayam.

- ^ "Ancient Churches, Stone Crosses of Kerala- Saint Thomas Cross, Nazraney Sthambams and other Persian Crosses". Nasrani.net. 16 January 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "Religion and Death". Kadamattomchurch.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Winckworth, C. P. T (April 1929). "A New Interpretation of the Pahlavi Cross-Inscriptions of Southern India". The Journal of Theological Studies. 30 (119). Oxford University Press: 237–244. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXX.April.237. JSTOR 23950669.

- ^ "2.2.8". ഉദയംപേരൂർ സുന്നഹദോസ് നിശ്ചയങ്ങൾ - രണ്ടാം മൗത്വ, രണ്ടാം കൂടിവിചാരം, എട്ടാം കാനോന [Decisions of the Synod of Diamper] (in Malayalam). Diamper, Kerala. 1599.

- ^ nl:Chaldean Syrian Church

- ^ Mar Severius, Dr. Mathews (23 February 2001). "സുറിയാനി സാഹിത്യ പഠനത്തിന്റെ സാംഗത്യം". In John, Kochumariamma (ed.). മലങ്കരയുടെ മല്പാനപ്പച്ചൻ [The Scholarly Father of Malankara] (in Malayalam). Johns and Mariam Publishers, Kottayam. pp. 185–192.

- ^ Mooken, Mar Aprem (1976). പൗരസ്ത്യ സഭാചരിത്ര പ്രവേശിക [Introduction to Eastern Church History] (in Malayalam). Thiruvalla. p. 95.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thomas, Dr. M. Kurian (2008). അഞ്ചാം പാത്രിയര്കീസ് മാർ ഗ്രീഗോറിയോസ് അബ്ദൽ ജലീദ് [Mar Gregorios Abdal Jaleed, the Fifth Patriarch] (in Malayalam). India: Sophia Books, Kottayam. p. 32.

- ^ Niranam Granthavari (Record of History written during 1770–1830). Editor Paul Manalil, M.O.C.Publications, Catholicate Aramana, Kottayam. 2002, p158.

- ^ Yakub III, Ignatius (2010). ഇന്ത്യയിലെ സുറിയാനി സഭാ ചരിത്രം [History of the Syrian Church in India] (in Malayalam). Cheeramchira. p. 210.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thomas, Dr. M. Kurian; Thottappuzha, Varghese John (6 October 2021). "മലങ്കര അസോസിയേഷൻ: 1653 മുതൽ 2020 വരെ" [Malankara Association: from 1653 to 2020]. www.ovsonline.in (in Malayalam).

- ^ Thomas, Dr. M. Kurian (July 2017). "19. സഹായത്തിൻ്റെ ദൗത്യത്തിൽനിന്ന് അധികാരത്തിൻ്റെ അകത്തളത്തിലേയ്ക്ക്" [From mission of help to foyer of subjugation]. നസ്രാണി സംസ്കൃതി [Nasrani Culture] (in Malayalam). Kottayam: Sophia Books. p. 131.

Bibliography

[edit]- Samuel Giamil, ed. (1902). Brevis notitia historica circa Ecclesiae Syro-Chaldaeo-Malabaricae statum. Genuinae relationes inter sedem apostolicam et Assyriorum orientalium seu Chaldaeorum ecclesiam. Rome: Loescher. pp. 552–64.

- Chronicle of Se'ert: Scher, Addai. Histoire nestorienne inédite: Chronique de Séert. pp. PO 4.3, 5.2, 7.2, 13.4. (editions issued: 1908, 1910, 1911, 1919).

- Cosmas Indicopleustes. W. Wolska-Conus (ed.). Christian Topography. Topographie chrétienne. Vol. 3 Sources chrétiennes. Paris: Éditions du Cerf. pp. 141, 159, 197. (editions issued: 1968, 1970, 1973).

- da Cunha Rivara, J. H., ed. (1992) [1862]. Diamper Synod, Acts of. Archivo Portuguez-Oriental, Fasciculo 4o que contem os Concilios de Goa e o Synodo de Diamper. Nova-Goa: Imprensa Nacional. Reprint: New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1992. pp. 283–556.

- Dionysio (1970) [1578]. Josephus Wicki (ed.). Relatio P. Francisci Dionysii S. I. De Christianis S. Thomae Cocini 4 Ianuarii 1578. Documenta Indica XI (1577–1580). Roma: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu. pp. 131–43. ISBN 9788870411232.

- A. S. Ramanatha Ayyar., ed. (1927). Funerary Inscription of the Last Villarvattam King. The Travancore Archaeological Series VI/1. pp. 68–71.

- George of Christ (1970) [1578]. Josephus Wicki (ed.). Rev. Georgius de Christo, Archidiaconus Christianorum S. Thomae, P. E. Mercuriano, praep. gen. S. I. Cocino 3 Ianuarii 1578. Documenta Indica XI (1577–1580). Roma: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu. pp. 129–31.

- Goes, Damião de. (1619). Chronica do Felicissimo Rey Dom Emmanuel da gloriosa memoria. Lisbon: Antonio Alvares.

- Gouvea, Antonio. (1606). Jornada do Arcebispo de Goa Dom Frey Aleixo de Menezes Primaz da India Oriental, Religioso da Orden de S. Agostino. Coimbra: Officina de Diogo Gomez.

- English translation: Malekandathil, Pius (2003). Jornada of Dom Alexis de Menezes: A Portuguese Account of the Sixteenth Century Malabar. Kochi: LRC Publications.

- M. R. Raghava Varier; Kesavan Veluthat (2013). "Kollam Copper Plates". Tarisāppaḷḷippaṭṭayam (Caritram) [The Tarissāppaḷḷi Document] (in Malayalam). Kottayam: National Book Stall Sahithya Pravarthaka C. S. Ltd. pp. 109–113.

- Kollam Copper Plates in English translation: Narayanan, M. G. S. (1972). Cultural Symbiosis in Kerala. Trivandrum: Kerala Historical Society. pp. 91–94.

- A. S. Ramanatha Ayyar, ed. (1927). Kumari-Muṭṭam Tamil Inscription. The Travancore Archaeological Series VI/1. pp. 176–89.

- Josephus Simonius Assemani, ed. (1725). Letter of Mar Thomas, Mar Yahballāhā, Mar Jacob and Mar Denḥā to Patriarch Mar Eliah V. Bibliotheca Orientalis Clementino-Vaticana, vol. III/1. Rome: Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide. pp. 589–99.

- Marco Polo the Venetian, The Travels of: Trans. John Masefield. Everyman’s Library London-New York: J. M. Dent and Sons-E. P. Dutton and Co. 1908.

- [Traditional] (1931). "Mārggam Kaḷi Pāṭṭu" [The Song of the Drama of the Way]. In H. Hosten (ed.). The Song of Thomas Ramban – Mr. T. K. Joseph, vs Fr. Romeo Thomas, T.O.C.D. and Others. Translated by Joseph, T. K. Darjeeling.

- Republished in: George Menachery (1998). Indian Church History Classics. Vol. One: The Nazranies. Pallinada, Ollur, Thrissur: The South Asia Research Assistance Services. pp. 522–525.

- Monserrate, Antonio de (1579). Informacion de los Christianos de S. Thomé. Archivum Romanum Societatis Jesu, MS Goa 33. Manuscript preserved in Rome.

- Periplus Maris Erythraei: K. Müller. 1855/1965. Geographi Graeci minores, vol. 1. Paris, Hildesheim (reprint): Firmin Didot, Olms (reprint). 1965. pp. 515–62.

- Roz, Francisco (1928). "Relação sobre a Serra. De erroribus Nestorianorum qui in hac India orientali versantur British Library, Add 9853, ff. 86 (525)–99 (539)". Inédit latin-syriaque de la fin de 1586 ou du début de 1587, retrouvé par le P. Castets S. I., missionaire à Trichinopoly, in I. Hausherr. Orientalia Christiana 11,1 (40): 1–35.

- Zaynuddin Makhdum (2012). K. M. Mohamed (ed.). Tahrid ahlil iman 'ala jihadi' abdati sulban [Exhortation to the followers of the Faith to the holy war against the followers of the Cross]. Calicut: Other Books.

- Zaynuddin Makhdum (2009). Muhammad Husayn Nainar (ed.). Tuḥfat al-Mujāhidīn: A Historical Epic of the Sixteenth Century. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Book Trust.