Laurynas Ivinskis

Laurynas Ivinskis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 August 1810 Šilalė parish, Russian Empire |

| Died | 29 July 1885 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | Lithuanian |

| Occupation(s) | Teacher, publisher, translator, lexicographer, botanist |

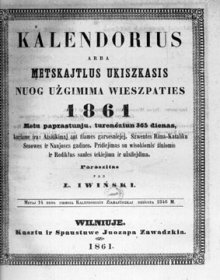

| Notable work | Calendars of Laurynas Ivinskis |

| Movement | Lithuanian National Revival |

Laurynas Rokas Ivinskis (15 August 1810 – 29 July 1881) was a Lithuanian teacher, publisher, translator, and lexicographer. He is best known for a series of annual calendars published between 1846 and 1877. The calendars were the first to publish Antanas Baranauskas' most famous poem The Forest of Anykščiai.

Born into a Samogitian noble family, Ivinskis attended gymnasium in Kolainiai. His studies were interrupted by the Uprising of 1831. He did not have funds for a university and worked as a tutor for various local noble families. In 1854, Ivinskis managed to get a job at a government-run primary school and taught in Rietavas and Joniškėlis. In 1864, Tsarist authorities enacted the Lithuanian press ban which prohibited to publish Lithuanian texts in the Latin alphabet. Ivinskis joined a government commission which worked to publish Lithuanian texts in the Cyrillic script. He started opposing the press ban and left the commission in 1866. He returned to tutoring. His students included Gabrielė Petkevičaitė-Bitė, brothers Gabriel and Stanisław Narutowicz, and Vladimir Zubov. In 1874–1879, Ivinskis worked as a teacher at a music school established in Rietavas by Bogdan Michał Ogiński.

During his life, Ivinskis published only two works – his annual calendars and Genovaitė, a translation of sentimental story Genovefa by Christoph von Schmid. The calendars were the first periodic Lithuanian publication in the Russian Empire. They included articles with practical medical, agricultural, etc. advice to Lithuanian peasants. The calendars are valued for including a literary section which published examples of Lithuanian folklore, didactic stories, and original and translated poems. His translations of Night-Thoughts and A Poem on the Last Day by Edward Young were published in 1890s in the United States. In 1856, he worked on establishing Aitvaras, the first Lithuanian newspaper, but the project was not approved by the Tsarist authorities. Ivinskis wrote many other works, including three unfinished Lithuanian dictionaries and a Lithuanian grammar. His illustrated mushroom atlas was to be exhibited at the 1873 Vienna World's Fair but was lost in transit. He established contacts with the Russian Geographical Society and sent them a collection of Lithuanian proverbs and riddles.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Ivinskis was born on 15 August [O.S. 3 August] 1810 in the parish of Šilalė to family of landless Samogitian nobles.[1] Before researcher Vytautas Merkys discovered his baptismal records in 1988, his place of birth was indicated as Bambalai near Užventis based on memoirs of Ivinskis' friend Aleksandras Moras.[1] Since his parents did not own land, they rented farms from nobles and moved frequently. Ivinskis grew up in Dargiai near Laukuva and Kaupos near Tverai where his parents rented a farm from bishop Juozapas Arnulfas Giedraitis.[2]

Around 1820, the family moved to Bambalai and Ivinskis enrolled at a gymnasium in nearby Kolainiai in 1824. The gymnasium was maintained by the Carmelites.[3] Ivinskis was a good student and chose to study all languages that were offered as electives.[4] In 1830, he graduated from the 3rd grade and was supposed to continue studies at the 4th grade. However, due to the Uprising of 1831 and lack of students, the school canceled the 4th grade.[5]

Home teacher

[edit]Due to the uprising, Vilnius University was closed and Ivinskis had no money for Russian universities. Therefore, he worked as a tutor of local noble children near Kuršėnai. This period of Ivinskis' life is poorly documented.[6] In 1841, Ivinskis passed exams and received an official home teacher's permit.[7] Around 1842, he moved near Rietavas. He continued to work as a teacher until about 1854. In his free time, he collected examples of Lithuanian folklore, attempted to write poetry, described local plant and fungus species.[8]

He prepared the first Lithuanian calendar in 1845, buy lacked fund for publication. He borrowed 60 Russian rubles from Ireneusz Kleofas Ogiński, the owner of the Rietavas Manor, and published the calendar at the Zawadzki printing shop in Vilnius.[9] His calendar was published annually until 1867. Ivinskis also worked on various other publications.[10]

In 1846, with the help of Ogiński, Ivinskis applied for a teaching job at a parish school in Rietavas.[11] However, he was rejected likely due to Russification policies which required Lithuanians to have at least five years of experience teaching in Russia.[12] In 1847, Ivinskis passed exams for an official city teacher's license, but still could not get a job at a government school.[12] In 1851–1854, he taught noble children in Pavirvytė, Naciūnai (Jurbarkas), Zabieliškis.[13]

School teacher

[edit]In 1854, Ivinskis finally obtained a teaching position at a school. He was assigned as a teacher to the parish school of Rietavas.[14] The two-year school had only two teachers and was meant to teach basic literacy skills to lower-class students. It focused on teaching religion, Russian and Polish languages, basic arithmetic, geography.[15] During his tenure at the school, the number of students grew from 59 in 1856 to 91 in 1862.[16] He worked there until 1862, which was the period of his peak productivity.[14]

He collaborated with the Zawadzki printing shop, helped curate its bookshop and establish a small reading room in Varniai.[17] He even considered quitting teaching and working on publishing and bookselling.[18] In 1856, he collaborated with bishop Motiejus Valančius and Mikalojus Akelaitis on establishing Aitvaras, the first Lithuanian-language newspaper in the Russian Empire.[19] It was intended to be a periodical with practical agricultural advice to Lithuanian peasants.[20] This effort coincided with a "thaw" in Russification efforts after the coronation of Alexander II of Russia and a change in personnel at the censorship office, but the project was not approved by the authorities.[21]

Ireneusz Kleofas Ogiński sponsored a two-year agricultural school in Rietavas, which opened in 1859. Ivinskis worked to organize the school, drafted its curriculum, etc. as well as taught general subjects.[22] He was interested in natural sciences, particularly botany, and purchased scientific books, a daguerreotype, and two microscopes.[23] In 1862, Ivinskis joined the Vilnius Archaeological Commission.[24]

Despite working for Ogiński, there is no evidence that Ivinskis received any payments from him. Ivinskis lived humbly on an annual teacher's salary of 150 rubles.[25] Therefore, Ivinskis looked for a new job. In 1860, he eyed a larger parish school in Joniškėlis which was better suited for his academic interests and closer to his family.[26] After the death of the old teacher, Ivinskis moved to Joniškėlis in April 1862.[27] His salary increased to 200 rubles.[28] The school was sponsored by the local noble Felicjan Stefan Karp who wanted to reform the four-year parish school into an agricultural school but the plans were interrupted by the Uprising of 1863.[29]

Lithuanian Cyrillic

[edit]In 1863, Tsarist government decided to establish a bilingual Belarusian–Lithuanian newspaper Drug Naroda in Vilnius. Ivinskis was invited to become the editor of the Lithuanian section. Despite the promised salary of 600 rubles, he refused and the newspaper was not established.[30]

After the Uprising of 1863, Tsarist authorities implemented a broad Russification policy. Hoping to bring Lithuanians into the Russian cultural sphere, they prohibited publishing Lithuanian texts in the Latin alphabet but encouraged Lithuanian publications using the Cyrillic script. Ivan Petrovich Kornilov, newly appointed administrator of the Vilna Educational District, established a commission to publish such Lithuanian Cyrillic texts in Kaunas.[31] Ivinskis, despite initial refusal, joined the commission in fall 1864.[32]

Ivinskis worked to publish his calendar in Cyrillic and write a Lithuanian Cyrillic primer.[33] He also worked to transcribe the popular Lithuanian prayer book Senas auksa altorius into Cyrillic, but his work was harshly criticized as sloppy and inaccurate.[33] He was tasked with transcribing gospels, Russian–Lithuanian grammar, texts from Russian history. However, his superiors complained that he did not have sufficient philological knowledge and that he purposefully delayed work.[33] He realized the harm of such publications on the Lithuanian identity and started opposing Lithuanian Cyrillic. He left the commission in spring 1866. He claimed that the government owed him 875 rubles for worked performed, but it was never paid.[34]

Retirement and tutoring

[edit]After 15 years of service in government jobs, Ivinskis resigned due to unspecified health reasons and was granted an annual pension of 30 rubles in April 1866. He felt cheated and claimed that his pension should be 50 rubles.[35] He moved back to Joniškėlis where he found shelter in the clergy house and received some assistance from Felicjan Stefan Karp. He struggled financially and would go days without food, but continued his academic work.[36] He became acquainted with town's pharmacist Leonas Petkevičius and began tutoring his daughter Gabrielė Petkevičaitė-Bitė.[37]

In 1868, Ivinskis briefly moved back to Rietavas to work at the library of Michał Mikołaj Ogiński.[38] In January 1869, he moved to Renavas.[38] Anton Rönne, owner of the Renavas Manor, took in widowed Wiktoria Narutowiczowa and her two sons, Gabriel and Stanisław Narutowicz, both future prominent prominent politicians in independent Poland and Lithuania.[39] Ivinskis taught them and other children of local nobility in Renavas and Lubiai.[40] He continued his academic work, spending summers collecting samples of plants and mushrooms. He drew over 2,000 pictures of the collected specimens.[41] He established contacts with the Russian Geographical Society and sent a copy of 2,133 Lithuanian proverbs and 353 riddles that he had collected over the years.[42] About half of the proverbs were taken from other published sources, but the other half was collected by Ivinskis from the people. For this, he was awarded society's silver medal.[42]

In 1871, Ivinskis moved to Šiauliai to teach Vladimir Zubov who started learning the Lithuanian language under his influence.[43][44] Despite difficult financial situation, Ivinskis attended the 1873 Vienna World's Fair, for which he prepared two exhibits: a mushroom atlas and a model of brakes for railway cars. However, the exhibits were lost in transit and were not displayed.[45] Around 1874, Ivinskis moved to Rietavas where he worked for five years as a teacher at a music school established by Bogdan Michał Ogiński.[46]

In 1879, Ivinskis moved to Milvydai near Kuršėnai where his old acquaintance Ignas Gružauskas agreed to provide shelter and support.[47] Ivinskis never married and had no children.[48] In early spring 1881, Ivinskis traveled to Rietavas for a meeting and caught a cold which turned into a kidney disease. Even in his last days, he continued to write and work on his dictionaries. He died on 29 July 1881 in Milvydai and was buried in Kuršėnai.[49]

Works

[edit]Calendars

[edit]

Calendars, or rather almanacs, compiled by Ivinskis were the first periodical Lithuanian publication in the Russian Empire.[50] In total, Ivinskis published 21 issues of his calendar in Russia: calendars for years 1846–1852, 1855–1864, and 1878 were printed in the Latin alphabet, while the 1865–1867 calendars were printed in the Cyrillic due to the Lithuanian press ban.[51] Due to the Russian censorship, the calendars for 1853 and 1854 were not published. Due to the press ban, Ivinskis published at least five calendars (1870, 1874, 1876, 1877, 1879) in Tilsit, East Prussia, from where it was smuggled into Russia.[52]

Until the press ban, the calendars were printed by the Zawadzki printing shop in Vilnius. Until 1855, Ivinskis financed the publication from his personal funds.[53] It was not a profitable undertaking and, in total, Ivinskis lost about 1,000 rubles publishing the calendars. When the calendars became more popular, Zawadzki printing shop agreed to finance the publication.[54]

The calendars were aimed at Lithuanian peasants.[55] The calendars included astronomical information, lists of religious feasts and important historical events, including from the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[56] The calendar was then followed by supplements which included articles on agriculture, medicine, veterinary science, and housekeeping.[57] From 1849 to 1855, the calendars included a religious section.[56] In 1849, Ivinskis published the first literary work (translation of A Poem on the Last Day by Edward Young). In 1851, the literary section became a firmly established part of the calendar.[56] The calendar ended with a list of fairs and markets held in various Lithuanian towns, table of sunsets and sunrises, and weather and harvest predictions.[53]

The content was original and not borrowed from similar Polish or Russian calendars.[53] They are valued for including a literary section which published examples of Lithuanian folklore, didactic stories, and original and translated poems.[58] In 1860–1861, the calendars were first to publish the epic poem The Forest of Anykščiai by Antanas Baranauskas which has become a classic work of Lithuanian literature. Other notable published authors included Silvestras Valiūnas, Dionizas Poška, Karolina Proniewska, Antanas Strazdas, and Jurgis Pabrėža.[59]

Translations

[edit]In 1853, Ivinskis wanted to publish a book of translated poetry. He translated excerpts from Night-Thoughts and A Poem on the Last Day by Edward Young and from Paradise Lost by John Milton. Ivinskis translated not form the original, but from the 1803 Polish translation by Franciszek Ksawery Dmochowski.[60] Russian censor particularly attacked Sūdna diena (translated A Poem on the Last Day) and ordered to delete 88 lines due to perceived antigovernmental sentiments.[61] Ivinskis' translation of Young's poems, shortened and edited, were published as separate booklets by Jonas Žilius-Jonila in the United States in 1897 and 1898.[62] Manuscripts of these translations were exhibited at the 1900 Paris Exposition.[63] Ivinskis' translation of Paradise Lost was not published. The shortened poem was translated into Lithuanian by Lionginas Pažūsis and published only in 2022.[64]

In 1859,[65] Ivinskis published Genovaitė, a translation of sentimental didactic story Genovefa by Christoph von Schmid. It is an adaptation of the medieval legend about Genevieve of Brabant.[66] Ivinskis translated the work from Polish, but adapted it to Lithuanian audience. For example, he changed character names to Lithuanian names, inserted scientific explanations for nature, anatomy, astronomy, added footnotes for Polish and Latin names of plants and mushrooms.[67] The work became popular and a second edition was published in 1863, becoming the first work of fiction in Lithuanian to be republished.[68] It was later republished by Martynas Jankus in Bitėnai in 1896, 1899, 1903, and 1904.[69] It popularized the names Genovaitė and Sigitas (from Siegfried) in Lithuania.[70] It is believed that Ivinskis also translated Boleslevas, the second part of Genovaitė about Genevieve's son who participated in the Crusades.[71] It was first published in Vienybė lietuvninkų and as a separate book in 1889 in Plymouth, PA.[72]

In 1847, Ivinskis translated Robinson Crusoe from a shortened Polish edition.[73] It included didactic lessons and a 195-word dictionary of less common words.[74] It remained unpublished and its manuscript was discovered only in 1961.[73]

In 1853, Ivinskis translated the History of the Old and the New Testaments and dedicated the manuscript to bishop Motiejus Valančius.[10] Its two parts had 1,079 pages.[75]

Dictionaries

[edit]Ivinskis started compiling several Lithuanian dictionaries, but they were unfinished and unpublished.[76]

His largest dictionary is the 2,688-page Polish–Lithuanian dictionary up to the letter S. The 2,060-page manuscript of 23,621 words up the letter R was discovered by Witold Armon in 1959 at the library of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences in Kraków.[77] It was gifted to the academy by Maria, wife of Bohdan Ogiński, with hopes that it could be published.[78] It is unknown what happened with the 628 pages devoted to the letter S,[77] though they were part of the Ivinskis' manuscript collection once owned by Petras Kriaučiūnas.[78]

Ivinskis used the two-volume Polish dictionary Słownik wileński published in 1861 as his primary source for the Polish words.[79] However, there are differences that reflect the variations between the standard Polish and the local Polish used in Samogitia.[80][81] The Lithuanian words mostly reflect Ivinskis' native Samogitian dialect, but he also attempted to include elements of the Aukštaitian dialect.[82] The dictionary is an important source for researchers of both Lithuanian and Polish languages. It was published by the Institute of the Lithuanian Language in 2010.[80]

Ivinskis also compiled a Russian–Lithuanian dictionary and sent 1,193 pages (up to the word Дешевый) to the Russian Geographical Society.[76] He also started compiling a Russian–Lithuanian–Latin–Polish dictionary. He sent the first 96 pages with 358 words up to Ay to the Geographical Society.[83] This sample contained 145 terms, mostly related to the natural sciences – names of minerals, plants, birds.[84]

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences holds two manuscripts by Ivinskis related to Lithuanian grammar: Polish tables with descriptions of Lithuanian declension and verb conjugation and 82-page Lithuanian grammar written in Polish.[85]

Botany and mycology

[edit]Ivinskis wrote a natural science work titled Prigimtūmenė was obtained by the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences in Kraków via the Polish botanist Edward Janczewski.[86][87] Its first part, 61-page Žemėmina,[88] describes non-living things in nature – rocks, metals, soil, bodies of water, bogs. The second part, Žolėmina, is a systemic list of plants and mushrooms based on the classification system of Carl Linnaeus.[86] The 218-page manuscript describes 219 families and more than 2,500 genera.[89] The names are provided in Latin with translations to Lithuanian, Polish, German. He also compiled alphabetical indexes in all four languages. He planned to write the third part about the animal kingdom, but it is unknown if he was able to start it as its manuscripts have not survived.[86] Since late 1990s, an effort is made to name new plants in Lithuanian using the names listed by Ivinskis in Prigimtūmenė.[90]

In 1873, Ivinskis prepared an atlas of mushrooms. It was selected by a congress of botanists in Warsaw to be exhibited at the 1873 Vienna World's Fair, but it was lost in transit.[91] Ivinskis then worked on a replacement atlas. Two parts of this atlas are known. They contain 226 pages with 769 drawings by Ivinskis.[91] Each mushroom is named in Latin; some names are translated to Lithuanian, Polish, German, Russian, or Czech. The mushrooms are described in Polish by noting their appearance, smell, taste, locations where they grow.[91]

It is known that Ivinskis collected Lithuanian plants, mushrooms, insects.[92] He drew over 2,000 botanical pictures.[41] Some of the collected examples were lost when his carriage rolled over around 1866, but he started over.[36] He gifted some of the collection to his student Vladimir Zubov and the Ogiński family, but they have not survived.[93] In 1878, at an agricultural exposition in Rietavas, Ivinskis presented his plans for a botanical garden based on works by the Austrian botanist Stephan Endlicher but they were not realized.[94]

Other unpublished works

[edit]Ivinskis manuscripts and personal archive were saved by Kajetonas Gadliauskas who transferred them to Petras Kriaučiūnas. He then donated the archive to the Lithuanian Scientific Society (now Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore).[95]

In 1851, Ivinskis prepared a collection of short stories titled Pasakos (Tales) for publication, but it was not printed and its manuscript was lost. It is likely that a few of these short stories were later published in his calendar.[96]

For the 1855 calendar, Ivinskis prepared and engraved a map of Telšiai powiat.[97] The map, measuring an arshin (71.12 centimetres or 28.00 inches), would have been the first published map in the Lithuanian language, but it was not published and map was lost.[98]

In 1875, he wrote a 51-page entitled Pasauga kiekvieno gyvo sutvėrimo (Care of Every Living Creature), which is considered the first Lithuanian work dedicated to the theme of environmental protection. It is a collection of 30 short didactic stories about care and protection of animals, tress, and plants.[99] Russian censors in Saint Petersburg initially approved the publication, but discovered their error when the type was already set.[100]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1883, Jonas Basanavičius published a list of manuscripts and main accomplishments by Ivinskis in Aušra. He also encouraged others to write their memoirs about Ivinskis.[63] A monograph about Ivinskis was published in 1988.[101] His selected works and bibliographic index were published in 1995.[102]

In 1938, there were plans of constructing a monument to Ivinskis in Rietavas, but it was not accomplished due to lack of funds. A monument by sculptor Petras Aleksandravičius was unveiled in Kuršėnai in 1961. Central square in Kuršėnai was named after Ivinskis.[63] Inspired by Ivinskis, Sigita Lukienė started collecting calendars in 1980. This collection was turned into the Calendar Museum which opened in 1996 in Kuršėnai.[103] The museum has a section dedicated to Ivinskis and well to winners of the annual Laurynas Ivinskis Prize established in 1990 and awarded by the Šiauliai District Municipality for the best calendar of the year.[103]

In 2010, for Ivinskis' 200th birth anniversary, memorial plaques to Ivinskis were installed at the church of Šilalė, the location of the former school in Kolainiai, Rietavas Manor, and the Samogitian Diocese Museum. The anniversary was commemorated with several events, including an academic conference and several exhibitions.[104]

In 1924, a street in Aukštieji Šančiai (Kaunas) was named after Ivinskis.[102] Since then, other streets were named after him in Vilnius, Kuršėnai, Kulautuva, Rietavas. Gymnasium in Rietavas was named after Ivinskis in 1920s (it was renamed during the Soviet period, but Ivinskis name was restored in 1988).[105] Gymnasium in Kuršėnai was named after Ivinskis in 1996.[106]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 8.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 10.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 11.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 22.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 27.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 28.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 29, 31.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 34.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 31.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 32.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 33–34, 37.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 38.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 42.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 41.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 44.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 114.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 51–52, 56.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 59.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 64.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 67.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 64, 66.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 74.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 76.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 79.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 81.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 82.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 83.

- ^ Vaitekūnas 2012, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 84.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 86.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 88–89, 160.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 89, 92.

- ^ Rudokas 2012, p. 85.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 96.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 102.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 107.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 103.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 230.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 123.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 124.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 231.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 122.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 123, 235–239.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 150, 161, 171.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 171.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 212.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 213–214.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 105.

- ^ Pažūsis 2022, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 219, 224.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 225.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 224.

- ^ Biržiška 1990, p. 186.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 226.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Biržiška 1990, p. 185.

- ^ a b Sabaliauskas 1979, p. 38.

- ^ a b Venckutė 2011, p. 284.

- ^ a b Palionis 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Palionis 2011, p. 182.

- ^ a b Palionis 2011, p. 187.

- ^ Venckutė 2011, p. 285.

- ^ Palionis 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 2007, p. 73.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 2007, p. 90.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 1998, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b c Zemlickas 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 1998, p. 107.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 1998, p. 102.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 1998, p. 106.

- ^ Auksoriūtė 2008, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b c Auksoriūtė 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 81, 84.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 92, 94.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 104.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 188.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 125.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 35–36, 125.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 99, 193–194, 230.

- ^ Merkys 1994, p. 128.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988.

- ^ a b Kauno apskrities viešoji Ąžuolyno biblioteka. "Ivinskis Laurynas Rokas" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Kuršėnų kalendorių muziejus". trip.lt (in Lithuanian).

- ^ Zemlickas 2011, p. 9.

- ^ "Apie gimnaziją" (in Lithuanian). Rietavo Lauryno Ivinskio gimnazija. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Gimnazijos istorija" (in Lithuanian). Šiaulių r. Kuršėnų Lauryno Ivinskio gimnazija. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Auksoriūtė, Albina (1998). "Lauryno Ivinskio rankraščiai Krokuvoje". Terminologija (in Lithuanian). 5: 102–110. ISSN 1392-267X.

- Auksoriūtė, Albina (2000). "L. Ivinskio mikologijos terminai" (PDF). Terminologija (in Lithuanian). 7: 48–58. ISSN 1392-267X.

- Auksoriūtė, Albina (2007). "Lauryno Ivinskio keturkalbio žodyno terminai" (PDF). Terminologija (in Lithuanian). 14: 72–91. ISSN 1392-267X.

- Auksoriūtė, Albina (2008). "Keletas atgaivintų Lauryno Ivinskio augalų vardų". Terminologija (in Lithuanian). 15: 132–141. ISSN 1392-267X.

- Biržiška, Vaclovas (1990) [1965]. Aleksandrynas: senųjų lietuvių rašytojų, rašiusių prieš 1865 m., biografijos, bibliografijos ir biobibliografijos (in Lithuanian). Vol. III. Vilnius: Sietynas. OCLC 28707188.

- Merkys, Vytautas (1994). Knygnešių laikai 1864–1904 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras. ISBN 9986-09-018-0.

- Navickienė, Aušra (2022). "How Did the Translation of Genovefa by Christoph Von Schmidt Become the 19th-Century Lithuanian Bestseller?". Knygotyra. 78: 80–110. ISSN 2345-0053.

- Palionis, Jonas (2011). "Lauryno Ivinskio lenkų-lietuvių kalbų žodynas". Acta linguistica Lithuanica (in Lithuanian). 64/65: 180–188. ISSN 1648-4444.

- Petkevičiūtė, Danutė (1988). Laurynas Ivinskis (in Lithuanian). Mokslas. ISBN 5-420-00104-7.

- Pažūsis, Lionginas (2022). "Džonas Miltonas ir jo epinė poema "Prarastasis rojus"" (PDF). Prarastasis rojus. By Milton, John (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos rašytojų sąjungos leidykla. ISBN 9786094802911.

- Rudokas, Jonas (2012). "Zubovų fenomenas". Kultūros barai (in Lithuanian). 2: 83–88. ISSN 0134-3106.

- Sabaliauskas, Algirdas (1979). Lietuvių kalbos tyrinėjimo istorija, iki 1940 m. (in Lithuanian). Mokslas. OCLC 874511621.

- Vaitekūnas, Stasys (2012). Stanislovas Narutavičius: signataras ir jo laikai (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras. ISBN 9785420017135.

- Venckutė, Regina (2011). "Lauryno Ivinskio lenkų-lietuvių kalbų žodynas". Archivum Lithuanicum (in Lithuanian). 13: 283–296. ISSN 1392-737X.

- Zemlickas, Gediminas (6 January 2011). "Lietuvišką pasaulį kūręs savyje ir tautoje". Mokslo Lietuva (in Lithuanian). 1 (445): 8–9, 12. ISSN 1392-7191.

- 1810 births

- 1881 deaths

- Lithuanian schoolteachers

- Lithuanian botanists

- Lithuanian lexicographers

- Lithuanian publishers (people)

- Mycologists

- Publishers (people) from the Russian Empire

- Translators from the Russian Empire

- Schoolteachers from the Russian Empire

- Lexicographers from the Russian Empire

- Translators to Lithuanian

- Lithuanian folk-song collectors

- People from Kelmė District Municipality

- 19th-century translators

- 19th-century lexicographers