Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Czech. (February 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | KSČM |

| Chairwoman | Kateřina Konečná |

| First Vice-Chairman | Petr Šimůnek |

| Deputy Leaders | Marie Pěnčíková Leo Luzar Milan Krajča |

| Founded | 31 March 1990 |

| Preceded by | Communist Party of Czechoslovakia |

| Headquarters | Politických vězňů 9, Prague |

| Newspaper | Haló noviny |

| Think tank | Institute of the Czech Left |

| Youth wing | Young Communists |

| Membership (2024) | 16,000 |

| Ideology | Communism[6] Anti-capitalism[7] Euroscepticism[10] Cultural conservatism[14] |

| Political position | Left-wing to far-left[A] |

| National affiliation | Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (1990–1992) Left Bloc (1992–1994) Stačilo! (since 2023) |

| European affiliation | Party of the European Left (observer) |

| European Parliament group | The Left (2004–2024) Non-Inscrits (since 2024)[15] |

| International affiliation | IMCWP World Anti-Imperialist Platform[16] (disputed) |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | "S lidmi pro lidi!" ('With the people for the people!') |

| Chamber of Deputies | 0 / 200 |

| Senate | 0 / 81 |

| European Parliament | 1 / 21 |

| Regional councils | 32 / 675 |

| Local councils | 466 / 62,300 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| kscm.cz | |

^ A: The party is also described as left-conservative,[17] given its more conservative stances on sociocultural issues.[19] | |

| Part of a series on |

| Communist parties |

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Czech: Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM) is a communist party[20] in the Czech Republic.[21] As of 2022, KSČM has a membership of 20,450.[22] Sources variously describe the party as either left-wing[23][24] or far-left[25][26] on the political spectrum. It is one of the few former ruling parties in post-Communist Central Eastern Europe to have not dropped the Communist title from its name, although it has changed its party program to adhere to laws adopted after 1989.[27][28] It was previously a member party of The Left group in the European Parliament,[29] and an observer member of the European Left Party,[30] but is now unaffiliated.

For most of the first two decades after the Velvet Revolution, the party was politically isolated and accused of extremism, but later moved closer to the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD).[28] After the 2012 Czech regional elections, KSČM began governing in coalition with the ČSSD in 10 regions.[31] It has never been part of a governing coalition in the executive branch but provided parliamentary support to Andrej Babiš' Second Cabinet until April 2021. The party's youth organization was banned from 2006 to 2010,[28][32] and there have been calls from other parties to outlaw the main party.[33] Until 2013, it was the only political party in the Czech Republic printing its own newspaper, called Haló noviny.[34] The party's two cherry logo comes from the song Le Temps des cerises, a revolutionary song associated with the Paris Commune.[35]

History

[edit]The party was formed in 1989 by a congress of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), which decided to create a party for the territories of Bohemia and Moravia (including Czech Silesia), the areas that were to become the Czech Republic. The new party's organization was significantly more democratic and decentralized than the previous party, and gave local district branches of the party significant autonomy.[36]

In 1990, KSČ was reorganized as a federation of KSČM and the Communist Party of Slovakia (KSS). Later, KSS changed its name to the Party of the Democratic Left, and the federation dissolved in 1992. During the party's first congress, held in Olomouc in October 1990, party leader Jiří Svoboda attempted to reform the party into a democratic socialist one, proposing a democratic socialist program and changing the name to the transitional Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia: Party of Democratic Socialism.[37] Svoboda had to balance the criticisms of older, conservative communists, who made up a majority of the party's members, with the demands of an increasingly large and moderate bloc of members, led primarily by a group of young KSČM parliamentarians called the Democratic Left, who demanded the immediate social democratization of the party. Delegates approved the new program but rejected the name change.[27]

During 1991 and 1992, factional tensions increased, with the party's conservative, anti-revisionist wing increasingly vocal in criticizing Svoboda. There was an increase in popularity of the anti-revisionist Marxist–Leninist clubs amongst rank-and-file party members. On the party's other wing, the Democratic Left became increasingly critical of the slow pace of the reforms and began demanding a referendum of members to change the name. In December 1991, the Democratic Left split off and formed the short-lived Party of Democratic Labour. The referendum on changing the name was held in 1992, with 75.94% voting not to change the name.[27]

The party's second congress, held in Kladno in December 1992, showed the increasing popularity of the party's anti-revisionist wing. It passed resolutions reinterpreting the 1990 program as a "starting point" for KSČM, rather than a definitive statement of a post-communist program. Svoboda, who was hospitalized due to an attack by an anti-communist, could not attend the congress but was nevertheless overwhelmingly re-elected.[27] After the party's second congress in 1992, several groups split away. A group of post-communist delegates split off and merged with the Party of Democratic Labour to form the Party of the Democratic Left (SDL). Several independent left-wing members who had participated with KSČM in the 1992 electoral pact, which was called the Left Bloc, left the party to form the Left Bloc Party.[36] Both groups eventually merged into the Party of Democratic Socialism.[38]

In 1993, Svoboda attempted to expel the members of the "For Socialism" platform, a group in the party that wanted a restoration of the pre-1989 Communist regime;[39] however, with only the lukewarm support of KSČM's central committee, he briefly resigned. He withdrew his resignation after the central committee agreed to move the party's next congress forward to June 1993 to resolve the issues of its name and ideology.[36] At the 1993 congress, held in Prostějov, Svoboda's proposals were overwhelmingly rejected by two-thirds majorities. Svoboda did not seek re-election as chairman, and neocommunist Miroslav Grebeníček was elected chairman. Grebeníček and his supporters were critical of what they termed the inadequacies of the pre-1989 regime but supported the retention of the party's communist character and program. The members of the "For Socialism" platform were expelled at the congress, with the existence of platforms in the party being banned altogether, on the grounds that they gave too much influence to minority groups. Svoboda left the party.[36]

"Conservative elements within the KSČM" were described as dominating the party's May 2004 Congress.[40]

The expelled members of "For Socialism" formed the Party of Czechoslovak Communists, later renamed the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which was led by Miroslav Štěpán.[38] KSČM refuses to work with this group. The party was left on the sidelines for most of the first decade of the Czech Republic's existence. Václav Havel suspected KSČM was still an unreconstructed neo-Stalinist party and prevented it from having any influence during his presidency; however, the party provided the one-vote margin that elected Havel's successor Václav Klaus as president.[41] After a long-running battle with the Ministry of the Interior, the Communist Youth Union led by Milan Krajča, was dissolved in 2006 for allegedly endorsing in its program the replacement of private with collective ownership of the means of production.[32] The decision met with international protests.[42]

In November 2008, the Czech Senate asked the Supreme Administrative Court to dissolve KSČM because of its political program, which the Senate argued contradicted the Constitution of the Czech Republic. 30 out of the 38 senators who were present agreed to this request, and expressed the view that the party's program did not reject violence as a means of attaining power and adopted The Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx.[43] However, this was only a symbolic gesture, as according to the constitution only the cabinet may file a petition to the Supreme Administrative Court to dissolve a political party. For the first two decades after the end of communist rule in Czechoslovakia, the party was politically isolated. After the 2012 Czech regional elections, it started participating in coalitions with the Czech Social Democratic Party, forming part of the ruling coalition in 10 out of 13 regions.[31] From 2018 to 2021, KSČM provided parliamentary support to Andrej Babiš' second cabinet.[44][45]

In November 2018, the KSČM supported an amendment with several other political parties in the Czech parliament aimed at extending marriage to same-sex couples.[46]

After the party's poor performance in the 2021 Czech legislative election, in which KSČM failed to reach the 5% voting threshold and was excluded from representation in parliament for the first time in its history, Filip resigned as leader of the party.[47] On 23 October 2021, Member of European Parliament Kateřina Konečná was elected as leader.[48]

In 2025, the Czech government passed an amendment to the national criminal code that introduces up to five years of prison for anyone who "establishes, supports or promotes Nazi, communist, or other movements which demonstrably aim to suppress human rights and freedoms or incite racial, ethnic, national, religious or class-based hatred". KSČM condemned the law, describing it as an attempt "to push KSČM outside the law and intimidate critics of the current regime".[49] The amendment will come to force in 2026; it is not clear how the amendment will affect the party - in an interview with Novinky, constitutional lawyer Jan Kysela argued that while KSČM's existence might not be in danger, the law could result in legal actions against its members.[50]

Ideology

[edit]As a communist party and the successor of the former ruling Communist Party of Czechoslovakia,[51] its party platform promotes anti-capitalism[52] and socialism.[53][54] Unlike other communist parties in post-communist Europe, KSČM "refused to break away with its communist past and largely preserved its Marxist agenda".[55] The party is also described as national communist.[56] It is classified as a radical left party.[57] It holds Eurosceptic views in regards to the European Union,[61] and has been described as pro-Russian,[62] pro-Chinese,[63] left-authoritarian in that it "combines cultural conservativism with an economic left-wing stance",[18] nativist,[64] and left-conservative.[17] It is conservative on sociocultural matters.[65] The Green European Journal described it as "culturally conservative, Islamophobic, and anti-EU, with many pro-Russian and openly far-right personalities in its ranks."[11] Political scientist Luke March compares the party to the Russian KPRF:

In particular, they are relatively weakly influenced by post-68 new left ideas or Eurocommunism, and some evidence of environmentalism in KSCM and KPRF platforms notwithstanding, these two parties remain far more socially conservative, materialist, and national-chauvinist than more reformist parties such as Rifondazione and even the PCF.[66]

The party's platform is considered to be based on key tenets of socialist ideology, as it supports the re-nationalization of the water, gas, electricity and transportation industries, the expansion of worker cooperatives, and the introduction of communally-owned firms based on the economic model of socialist Czechoslovakia. The party argues that everyone should have a guaranteed right to a job, receiving a salary that corresponds to how demanding the job is, and that the minimum wage should correspond to half the national average income. KSČM also promotes a system of non-profit hospitals and a single state-owned health insurance company. It says it would be willing to participate in non-socialist governments as long as its six demands are met: regular increases in both the minimum wage and pensions, expanding public ownership of water utilities, extraction of natural resources only by domestic companies, construction of communal housing, and abolishing patient fees in health care.[67]

Political scientist Maria Snegovaya wrote that "over the years, KSČM adopted a platform reminiscent of those used by populist right parties in other countries: protectionist on the economic dimension, Euroskeptic and nationalist on the sociocultural dimension". It rejects European integration as "capitalist" and "neoliberal", arguing that it is destructive to the living conditions of citizens and ignores "social issues". It also opposes Czech membership in NATO on nationalist grounds, calling NATO "US- and Germany-dominated" and naming it, alongside the Lisbon Treaty, as "a threat to Czech state sovereignty that led to the exploitation of Czech interests by multinational capitalist forces". The party's base is composed of voters who are dissatisfied with the functioning of Czech democracy, distrust public institutions, or live in areas with high levels of unemployment and crime.[68]

The party has been described as embracing "a socially conservative and nationalist platform in the democratic era".[69]

Leaders

[edit]| # | Name (Born–Died) |

Portrait | Term of Office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiří Machalík (1945–2014) |

|

31 March 1990 | 13 October 1990 |

| 2 | Jiří Svoboda (b. 1945) |

|

13 October 1990 | 25 June 1993 |

| 3 | Miroslav Grebeníček (b. 1947) |

|

25 June 1993 | 1 October 2005 |

| 4 | Vojtěch Filip (b. 1955) |

|

1 October 2005 | 9 October 2021 |

| 5 | Kateřina Konečná (b. 1981) |

|

23 October 2021 | present |

Electoral results

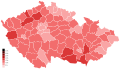

[edit]The voter base of KSČM is dominated by blue-collar workers and retired workers; it also preserves strong links to trade union activists, and 57% of its supporters are drawn from trade unions. About 20% of trade unions members are supporters of the KSČM. The party's membership and voter structure shows a disproportional share of blue-collar workers, and working-class voters in general.[70] The party is stronger among older than younger voters, with the majority of its membership over 60.[71] The party is also stronger in small and medium-sized towns than in big cities.[72]

Parliament

[edit]

Chamber of Deputies

[edit]| Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic | |||||||

| Year | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | ± | Place | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Jiří Machalík | 954,690 | 13.2 | 33 / 200

|

New | 2nd | Opposition |

| 1992 | Jiří Svoboda | 909,490 | 14.0[a] | 35 / 200

|

2nd | Opposition | |

| 1996 | Miroslav Grebeníček | 626,136 | 10.3 | 22 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 1998 | Miroslav Grebeníček | 658,550 | 11.0 | 24 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2002 | Miroslav Grebeníček | 882,653 | 18.5 | 41 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2006 | Vojtěch Filip | 685,328 | 12.8 | 26 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2010 | Vojtěch Filip | 589,765 | 11.3 | 26 / 200

|

4th | Opposition | |

| 2013 | Vojtěch Filip | 741,044 | 14.9 | 33 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2017 | Vojtěch Filip | 393,100 | 7.8 | 15 / 200

|

5th | Confidence and supply | |

| 2021 | Vojtěch Filip | 193,817 | 3.6 | 0 / 200

|

7th | No seats | |

- Notes

-

KSCM 1996

-

KSCM 1998

-

KSCM 2002

-

KSCM 2006

-

KSCM 2010

-

KSCM 2013

-

KSCM 2017

-

KSCM 2021

Senate

[edit]| Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic | |||||||

| Year | First round | Second round | No. of seats won | No. of overall seats won |

± | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| 1996 | 393,494 | 14.3 | 45,304 | 2.0 | 2 / 81

|

2 / 81

|

New |

| 1998 | 159,123 | 16.5 | 31,097 | 5.8 | 2 / 27

|

4 / 81

|

|

| 2000 | 152,934 | 17.8 | 73,372 | 13.0 | 0 / 27

|

3 / 81

|

|

| 2002 | 110,171 | 16.5 | 57,434 | 7.0 | 1 / 27

|

3 / 81

|

|

| 2004 | 125,892 | 17.4 | 65,136 | 13.6 | 1 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2006 | 134,863 | 12.7 | 26,001 | 4.5 | 0 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2008 | 147,186 | 14.1 | did not make it | did not make it | 1 / 27

|

3 / 81

|

|

| 2010 | 117,374 | 10.2 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2012 | 153,335 | 17.4 | 79,663 | 15.5 | 1 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2014 | 99,973 | 9.74 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

1 / 81

|

|

| 2016 | 83,741 | 9.50 | 5,737 | 1.35 | 0 / 27

|

1 / 81

|

|

| 2018 | 80,371 | 7.38 | 3,578 | 0.86 | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

| 2020 | 40,994 | 4.11 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

| 2022 | 17,612 | 1.60 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

| 2024 | 14,321 | 1.80 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

European Parliament

[edit]| Election | List leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | EP Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Miloslav Ransdorf | 472,862 | 20.27 (#2) | 6 / 24

|

New | GUE/NGL |

| 2009 | 334,577 | 14.18 (#3) | 4 / 22

|

|||

| 2014 | Kateřina Konečná | 166,478 | 10.99 (#4) | 3 / 21

|

||

| 2019 | 164,624 | 6.94 (#7) | 1 / 21

|

The Left | ||

| 2024[a] | 283,935 | 9.56 (#4) | 1 / 21

|

NI |

Local councils

[edit]| Year | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 17,413,545 | 13.6 | 5,837 / 62,160

|

| 1998 | 10,703,975 | 13.7 | 5,748 / 62,920

|

| 2002 | 11 696 976 | 14.5 | 5,702 / 62,494

|

| 2006 | 11,730,243 | 10.8 | 4,268 / 62,426

|

| 2010 | 8,628,685 | 9.6 | 3,189 / 62,178

|

| 2014 | 7,730,503 | 7.8 | 2,510 / 62,300

|

| 2018 | 5,416,907 | 4.9 | 1,426 / 62,300

|

| 2022 | 2,093,505 | 1.9 | 466 / 62,300

|

Regional councils

[edit]| Year | Votes | % | Seats | ± | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 496,688 | 21.1 | 161 / 675

|

New | 3rd |

| 2004 | 416,807 |

19.7 |

157 / 675

|

2nd | |

| 2008 | 438,024 |

15.0 |

114 / 675

|

3rd | |

| 2012 | 538,953 |

20.4 |

182 / 675

|

2nd | |

| 2016 | 267,047 |

10.6 |

86 / 675

|

3rd | |

| 2020 | 131,770 |

4.8 |

13 / 675

|

9th | |

| 2024[a] | 147,594 |

6.2 |

40 / 685

|

5th |

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kim, Seongcheol (14 October 2024). "Anti-Populism of the Left, Right, and Centre: Varieties of Anti-Populist Party Politics in the European 'Populist Moment'". Politische Vierteljahresschrift. doi:10.1007/s11615-024-00574-7. p. 13:

The ODS repeatedly denounced the "populism" of 'the left' (encompassing the social-democratic CSSD and the communist KSCM alike) and its 'social demagoguery' of promising supposedly endless public spending (Kim 2022).

- ^ a b Kossack, Oliver (2023). Pariahs or Partners? Patterns of Government Formation with Radical Right Parties in Central and Eastern Europe, 1990-2020. Edition Politik. Vol. 153. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. p. 70. doi:10.14361/9783839467152. ISBN 978-3-8394-6715-2.

Some of them, such as the Polish Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) or the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSzP), undertook credible reforms and transformed into socialist or social democratic parties, whereas the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM) in the Czech Republic maintained their orthodox Communist ideology after 1989.

- ^ a b Fila, Filip (2024). Perception of the European Union in the context of the migration crisis – a comparative study of the Czech Republic and Croatia (PDF) (Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences thesis). University of Zagreb. p. 62:

KSČM - Radical left (Communism)

- ^ a b Bednarek, Wojciech (2020). "Mała Moskwa nad Wełtawą – rosyjska społeczność w Republice Czeskiej w kontekście ładu społeczno-politycznego i bezpieczeństwa narodowego" [Little Moscow on the Vltava river – Russian communities in the Czech Republic in the context of socio-political order and homeland security] (PDF). Rocznik Instytutu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej. 18 (3). Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of Poland: 73–92. doi:10.36874/RIESW.2020.3.4. p. 82:

Among representatives of the Czech parliament, those involved in pro-Russian and anti-EU and anti-NATO programs share the views of two anti-system groups – the anti-immigrant SPD and the communist KSČM.

- ^ Gosling, Tim; Inotai, Edit; Szekeres, Edward; Ciobanu, Claudia (19 February 2021). "Democracy Digest: Lies, Damned Lies and COVID-19 Statistics". Balkan Insight. Reporting Democracy. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ [1][2][3][4][5]

- ^ Snegovaya, Maria (2018). Ex-Communist Party Choices and the Electoral Success of the Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). Columbia University. p. 129. CORE output ID 161515337.

Reflecting the party's ideological rigidity, the KSČM platform consistently stressed some of the Marxist dogmas, for example, identifying capitalism as the main disease afflicting world's population and offering to combine the Marxist collectivist goals with democratic objectives.

- ^ Marušiak, Juraj (2021). "The Czech Republic and Slovakia. Changing Perception of the European Integration since 1989". In Ostap Kushnir; Oleksandr Pankieiev (eds.). Meandering in Transition: Thirty Years of Reforms and Identity in Post-Communist Europe. Bloomsbury USA Print. pp. 115–116. doi:10.5040/9781666994421.ch-6.

As one may see, the Euroskeptic and pro-sovereign moods were much stronger in the Czech society and manifested themselves not only in criticism of some aspects of the EU's functioning, but in the rejection of the very idea of membership. The latter rejection was mostly fostered by the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, alongside selected representatives of ODS (e.g., party's vice-chairman Ivan Langer).

- ^ Fila, Filip (2024). Perception of the European Union in the context of the migration crisis – a comparative study of the Czech Republic and Croatia (PDF) (Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences thesis). University of Zagreb. p. 80:

What is notable is the addition of the highly Eurosceptic SPD to the competition; even if the communist KSČM party was known to tread the line between hard and soft Euroscepticism, the SPD is even more radical.

- ^ [8][9]

- ^ a b c Dvořáková, Petra (30 May 2024). "No Country for Progressive Women: European Elections in Czechia". Green European Journal.

The coalition Stačilo! ('Enough!'), led by the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, may gain a seat or two in the European Parliament this year, but this isn't good news for progressives. The Communist Party is culturally conservative, Islamophobic, and anti-EU, with many pro-Russian and openly far-right personalities in its ranks.

- ^ a b c Wondreys, Jakub (2020). "The "refugee crisis" and the transformation of the far right and the political mainstream: the extreme case of the Czech Republic". East European Politics. 37 (4). Taylor & Francis Group: 722–746. doi:10.1080/21599165.2020.1856088. p. 11:

That said, the KSČM has long combined far left socio-economic policies with quite conservative socio-cultural positions, so this is not necessarily out of line with party history.

- ^ a b c Císař, Ondřej [in Czech] (2017). "Czech Republic: From Post-Communist Idealism to Economic Populism" (PDF). International Policy Analysis. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. p. 8:

The most stable among them is the direct heir to the pre-1989 ruling party, the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM), usually classified as an example of »social populism«. The party remains nominally on the left due to its economic program, but it is clearly very authoritarian and conservative in its sociocultural orientation, mirroring the values of predominantly older generations longing for the lost times of real socialism before 1989.

- ^ [11][12][13]

- ^ "STAČILO! a frakce aneb program za koryta nevyměníme!". KSČM. 9 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Milan Krajča, Vice-President of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia(Czech Republic)". World Anti-Imperialist Platform. 17 May 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b Josef Bernard; Martin Refisch; Anna Grzelak; Jerzy Banski; Larissa Deppisch; Michal Konopski; Tomáš Kostelecký; Mariusz Kowalski; Andreas Klärner (2025). "Left-behind Regions in Poland, Germany, Czechia: Classification and Electoral Implications" (PDF). Thünen Working Paper (261).

KSČM – Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy (Communist party of Bohemia and Moravia) is a left-wing conservative populist party, the direct successor of the Communist Party that ruled before 1989, criticizing post-1989 political development and emphasizing social security issues.

- ^ a b Thomeczek, Jan Philipp (2024). "Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW): Left-Wing Authoritarian—and Populist? An Empirical Analysis". Politische Vierteljahresschrift. 65 (1). Springer: 535–552. doi:10.1007/s11615-024-00544-z.

Her public statements and books indicate that she appeals to the "left-wing authoritarians" (Lefkofridi et al. 2014), namely voters who hold economically left positions but are culturally conservative. [...] According to the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. 2019), there are several parties with a similar left-authoritarian profile in Europe. Examples are the Social Democratic Party in Romania (PSD), the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), and far-left parties such as the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSCM).

- ^ [18][12][13][11]

- ^ [1][2][3][4]

- ^ Nordsieck, Wolfram (October 2021). "Czechia". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ "Stranám ubývají členové. Rozrůstají se jen SPD a STAN". ČT24. 18 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Seelinger, Lani (11 July 2014). "Why the Czech Communists are here to stay". visegradrevue.eu. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ Pink, Michal (August 2012). "The Electoral Base of Left-Wing Post-Communist Political Parties in the Former Czechoslovakia". Central European Political Studies Review. 14 (2–3): 170–192. Retrieved 12 August 2019..

- ^ Kapsas, André (6 April 2018). "Andrej Babiš et les sociaux-démocrates tchèques négocient leur alliance". Courrier d'Europe centrale (in French). Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ Lopatka, Jan (30 April 2018). "New dawn or swan song? Czech communists eye slice of power after decades". Reuters. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 146.

- ^ a b c "Elections: What's on the menu". Prague Daily Monitor. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "European United Left & Nordic Green Left European Parliamentary Group delegations". Guengl.eu. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia". european-left.org. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b "ČSSD to rule along with Communists in 10 of 13 Czech regions". Prague Monitor. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Communists denounce ban on far-left youth movement". Radio Praha. 19 October 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Czech Activists Seek to Outlaw Communist Party". The New York Times. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ "Halonoviny.cz - české levicové zprávy". Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ "Kdo jsme". Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 147.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Hough, Dan; Handl, Vladimír (September 2004). "The post-communist left and the European Union: The Czech Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM) and the German Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS)". Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 37 (3): 319–339. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2004.06.002.

- ^ Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

- ^ "Czech Communist Youth Union outlawed". The Guardian. Communist Party of Australia. 25 October 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ "Komunisté ve světě nás nedají, říká o hrozbě rozpuštění šéf KSČM". iDnes, the online portal of Mladá fronta DNES. Czech News Agency. November 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ "ČSSD v referendu schválila vládu s ANO. Babiš však ještě nemá vyhráno". iDNES.cz. 15 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "Babiš je podruhé premiérem. Hájil, že vláda bude opřená o komunisty". iDNES.cz. 6 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "Czech Lower House debated Same-Sex Marriage". Rémy Bonny. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Vedení KSČM rezignovalo. Vstanou noví bojovníci, vzkázal Filip". iDNES.cz (in Czech). 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Novou šéfkou KSČM se stala Konečná. Vyhrála s velkou převahou". Novinky.cz (in Czech). 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Zachová, Aneta (18 July 2025). "Czech president signs law criminalising communist propaganda". Euractiv.

- ^ "Czechia Criminalizes Promotion of Communism from 2026". Prague Morning. 27 July 2025.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, pp. 150–153.

- ^ "Musíme vést třídní boj a zničit kapitalismus, řekla v Rozstřelu Konečná z KSČM". Idnes.cz. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ James Cronin; George Ross; James Shoch (2011). What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times. Durham and London: Duke University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-8223-5079-8.

In a subsequent document the KSČM publicly rejected the practices of former regimes but also put strong emphasis on its aim to create a modern socialist society, which will guarantee real and lasting freedom and equality, regardless of property and social status.

- ^ March, Luke [in Spanish] (2011). "The fall and (partial) rise of the Eastern European communists". Radical Left Parties in Europe. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-203-15487-8.

Moreover, the KSCM's documents show a commitment to a participative and pluralistic socialism.

- ^ Snegovaya, Maria (2024). When Left Moves Right: The Decline of the Left and the Rise of the Populist Right in Postcommunist Europe. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197699027.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-769902-7. p. 13:

I define parties as the traditional left if they constituted the part of the unreformed communist party that refused to break away with its communist past and largely preserved its Marxist agenda. Among the countries studied, only one electorally successful party represents such a clear-cut case: the Czech Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Komunisticka strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM), the successor to the Czechoslovak Communist Party in the Czech Republic.

- ^ Engler, Sarah; Pytlas, Bartek; Deegan-Krause, Kevin (2019). "Assessing the diversity of anti-establishment and populist politics in Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). West European Politics. 42 (6). Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich: 10–11. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1596696.

Parties with this ideological profile occupy a wide range on the unidimensional left–right spectrum in Figure 2, including the social-conservative right such as Poland's Law and Justice (PiS), the Hungarian Fidesz (Vachudova 2008; Pytlas 2015), nationalist communists (such as the Bulgarian BSP or the Czech KSČM), and even 11 mainstream left parties such as Direction (Smer) in Slovakia or Romania's Social Democratic Party (PSD) (cf. Pop-Eleches 2008; Pytlas 2013).

- ^ Guasti, Petra; Michal, Aleš (18 June 2025). "Polarization and Democracy in Central Europe". Politics and Governance. 13 9560. doi:10.17645/pag.9560. p. 9:

In the Czech political landscape, these parties are regarded as moderate, while SPD (Freedom and Direct Democracy) is classified as radical right and KSČM (Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia) as radical left.

- ^ "How Europe will break on Brexit". Politico.eu. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "O Brexitu neboli proč by EU měla jít". KSČM. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Krachující Evropská unie a Česká republika". KSČM. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ [58][59][60]

- ^ Ivaldi, Gilles; Zankina, Emilia (2023). The impact of the Russia–Ukraine War on right-wing populism in Europe. doi:10.55271/rp0010. p. 94:

After 2015, the SPD was among the few pro-Russian or pro-Putin political parties in the Czech parliament (alongside the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, which is no longer in the parliament).

- ^ Triglavcan, Patrick (2023). "The People's Republic of China: Political perceptions in Central Europe" (PDF). Geopolitics Programme. Council on Geostrategy. p. 52:

Members of ČSSD and ANO displayed more positive views regarding the PRC and embraced it pragmatically, while KSČM consistently projected a pro-Chinese position throughout the electoral cycles mentioned.

- ^ Snegovaya, Maria (2024). When Left Moves Right: The Decline of the Left and the Rise of the Populist Right in Postcommunist Europe. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197699027.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-769902-7. p. 206:

Populist parties then appealed to such voters by integrating redistributive appeals with their sociocultural conservative nativist stances on the sociocultural dimension. There are diferent trajectories for parties to get there. While PiS and Fidesz started with cultural conservatism, only later adding redistributionist positions, the Czech KSČM was on the left economically from the start but subsequently adopted nativist positions.

- ^ [12][13]

- ^ March, Luke [in Spanish] (2011). "The fall and (partial) rise of the Eastern European communists". Radical Left Parties in Europe. Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-203-15487-8.

Moreover, the KSCM's documents show a commitment to a participative and pluralistic socialism.

- ^ Stegmaier, Mary; Linek, Lukáš (26 July 2018). "The Communist Party is supporting the Czech coalition government. What are the implications?". Washington Post.

The KSCM's domestic platform emphasizes key tenets of socialist ideology — including the re-nationalization of key utilities such as water, gas, electricity and transportation.

- ^ Snegovaya, Maria (2024). When Left Moves Right: The Decline of the Left and the Rise of the Populist Right in Postcommunist Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 155–156. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197699027.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-769902-7.

- ^ Broszkowski, Roman (13 January 2023). "The Czech Left Faces a Long Road to Recovery". Jacobin. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Snegovaya, Maria (2018). Ex-Communist Party Choices and the Electoral Success of the Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). Columbia University. p. 131. CORE output ID 161515337.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 155.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 156.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bozóki, András; Ishiyama, John (2002). The Communist Successor Parties of Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7656-0986-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Hough, Dan; Paterson, William E.; Sloam, James, eds. (2005). Learning from the West? Policy Transfer and Programmatic Change in the Communist Successor Parties of East Central Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-37316-6.

External links

[edit]- Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia

- 1989 establishments in Czechoslovakia

- Anti-capitalist political parties

- Communist parties in the Czech Republic

- Conservative parties in Europe

- Eurosceptic parties in the Czech Republic

- Left-wing parties in the Czech Republic

- Far-left politics in the Czech Republic

- Marxist parties in the Czech Republic

- Parties represented in the European Parliament

- Party of the European Left observer parties

- Political parties established in 1989

- Political parties in Czechoslovakia

- International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties