Jeremiah Chamberlain

Jeremiah Chamberlain | |

|---|---|

| 1st President of Oakland College | |

| In office May 14, 1830 – September 5, 1851 | |

| Succeeded by | Robert L. Stanton |

| 1st President of the College of Louisiana | |

| In office 1826–1828 | |

| Succeeded by | Henry H. Gird |

| 2nd President of Centre College | |

| In office July 2, 1823 – September 1826 | |

| Preceded by | James McChord |

| Succeeded by | Gideon Blackburn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 5, 1794 Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | September 5, 1851 (aged 57) Lorman, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oakland College Cemetery Alcorn, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) |

Rebecca Blaine

(m. 1818; died 1836)Catharine Metzger (m. 1845) |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

Jeremiah Chamberlain (January 5, 1794 – September 5, 1851) was an American Presbyterian minister, educator and college administrator. He was president of three institutions of higher education between 1823 and 1851, specifically Centre College (1823–1826), the College of Louisiana (1826–1828), and Oakland College (1830–1851).

Born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to a former Continental Army colonel, Chamberlain studied under David McConaughy in his youth before enrolling at Dickinson College. He graduated from Dickinson in 1814 and later from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1817. Following a mission trip, he took his first pastorate at a Presbyterian church in Bedford, Pennsylvania, where he stayed from 1818 to 1822. He left upon his election as president of Centre College, which had been chartered nearly four years earlier and was struggling financially. During his time in Danville, Centre awarded its first five degrees and transferred governing authority to the church in exchange for financial support. Chamberlain left Centre in 1826 to become president of the College of Louisiana, a predecessor of Centenary College of Louisiana, and stayed until 1828. He then moved to Mississippi and made plans, later approved by the church, to open a school in Claiborne County. The school opened as Oakland College in May 1830; Chamberlain was its first president. He was strongly anti-slavery and helped to create the Mississippi Colonization Society during the 1830s.

Chamberlain was murdered at his home in 1851 by a planter named George Briscoe, who struck Chamberlain with a whip several times before fatally stabbing him in the chest. Most reports agree that the men were engaged in an argument, though the subject of the argument is disputed; some blame Chamberlain's anti-secession and anti-slavery views, while other reports make note of a student that was recently expelled from Oakland for a pro-secession speech as a possible motive. Chamberlain was buried two days later in Oakland College Cemetery, the same day Briscoe's body was found following his purported suicide. Oakland ultimately did not survive the Civil War and the death of another of its presidents; the campus was sold to the state of Mississippi in 1871 and reopened as what is now Alcorn State University.

Early life and education

[edit]Jeremiah Chamberlain was born January 5, 1794, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[1] His father was James Chamberlain, the son of immigrants from Ireland and a colonel with the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War,[2] and his mother was Ann Sample, from York County.[3] He was one of five sons (and one of nine children in total) in the family.[3] Jeremiah was raised on his family's farm near Gettysburg, and he received his primary education from a classical school in York County, Pennsylvania.[4] In 1809, aged fifteen, Chamberlain left the family farm to study under, and board with, the teacher and minister David McConaughy, described by the biographer William Buell Sprague as having "kept an excellent school for the preparation of young men for college".[3] He graduated from Dickinson College, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1814; after leaving Dickinson, he enrolled at Princeton Theological Seminary and was a member of its first graduating class in 1817.[4] Jeremiah's brother, John Chamberlain, also attended Dickinson and graduated in 1825; he was later a member of the faculty at Oakland from the college's opening until Jeremiah's death.[5]

Career

[edit]Starting in November 1817, shortly following Chamberlain's graduation from Princeton, he began mission work in the Old Southwest and visited Natchez, Mississippi; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Mobile, Alabama, on the trip.[6] In mid-1818, he was ordained as a minister by the Carlisle Presbytery and took his first ministry role as a preacher in Bedford, Pennsylvania.[7][3] The Bedford church had been organized around 1780 and Chamberlain is listed as its third pastor by church historian George Norcross.[8][a] Chamberlain also directed a classical school during his time at Bedford, and he preached from time to time at a church in Schellsburg.[3] In 1819, he was appointed to more missionary work by the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA), this time for six months in the Missouri Territory.[11]

On December 31, 1822, Chamberlain was elected president of a young Centre College in Danville, Kentucky.[7][b] Centre had been chartered by the Kentucky General Assembly in January 1819,[14] and its first president, James McChord, had died in May 1820, nearly three months after his election as president but before he actually ever took office.[16][c] Chamberlain entered office upon his formal inauguration on July 2, 1823.[7][18] He received an annual salary of $2,000 (equivalent to $47,200 in 2024) in the position.[7] He inherited a college in the midst of serious financial struggles; Centre was receiving financial assistance from neither the state legislature, which had inadequate resources to help, nor from the church, which did not wish to help since it did not control the school. Much of these financial woes were put to an end in 1824,[19] when an agreement was reached that the PCUSA take control of the school in exchange for a donation of $20,000 (equivalent to $573,000 in 2024).[7] Centre graduated its first five students over Chamberlain's three years in office; the first graduation, in 1824, featured two students, one of whom was future Centre president Lewis W. Green.[20] A new charter for the college was put into effect during Chamberlain's administration; among other things, it included a stipulation that the college could open a seminary, which it did in October 1828 with funding and personnel primarily provided by the PCUSA.[3][18] In addition to his administrative and teaching duties at Centre, Chamberlain preached and taught bible classes for the duration of his time in Danville.[3]

Chamberlain was voted president of the College of Louisiana, in Jackson, Louisiana (which later merged to become Centenary College of Louisiana) by the school's trustees on June 15, 1826. He won the vote over one William Walker of Massachusetts by a tally of eight to three.[21] Chamberlain accepted the position no later than December 1826,[22] and likely earlier as he had vacated Centre's presidency in September 1826.[18] His immediate successor at Centre was David C. Procter in an interim capacity for roughly seven months until Gideon Blackburn was appointed to the full-time role. Chamberlain was the first of three consecutive Dickinson-alumni presidents of Centre.[23]

In Louisiana, like at Centre, Chamberlain taught classes as part of his role as president, though only those for juniors and seniors;[24][d] he was paid $3,000 (equivalent to $83,400 in 2024) annually.[22] He was one of four members of the school's faculty, though one faculty member worked as principal of the preparatory department; the next additions to the faculty took place in 1829.[24] The first literary societies were founded at the College of Louisiana during Chamberlain's time there.[25] He resigned this position in 1828 in order to focus on opening his own school.[4][e] Henry H. Gird was later elected president and professor of mathematics by the board on April 1829; he had begun this role by November of that year.[28]

Chamberlain moved to Mississippi and began his efforts to open a school in mid-1828.[29] During this time, he preached at Bethel Presbyterian Church in Alcorn.[30] After presenting his plans to the Mississippi Presbytery, the school was approved and the PCUSA opened Oakland College in Claiborne County on May 14, 1830, with Chamberlain as president.[29][31] Its initial enrollment was three students, all of whom had come to Oakland from Louisiana,[27] though it grew to 65 students by the end of the first term.[31] The college received a charter from the Mississippi Legislature in 1831.[31][29] A donation of $20,000 (equivalent to $556,000 in 2024) by John Ker allowed Oakland to establish an endowed professorship in theology in 1837; the minister S. Beach Jones was the first person permanently appointed to the position, though he had left to take a pastorate in New Jersey by October 1838.[31][32] By 1839, the college's assets had grown to include a campus of 250 acres (0.39 sq mi), nineteen buildings, and an endowment approaching $100,000 (equivalent to $2.95 million in 2024).[31] Oakland received one of the largest donations to any antebellum Mississippi school, a $50,000 gift from the Natchez, Mississippi, businessman David Hunt, who donated roughly $150,000 in total to the school over its lifetime.[33] By 1850, Oakland had graduated roughly 100 students.[34]

Personal life

[edit]

Chamberlain married Rebecca Blaine (October 29, 1792 – October 12, 1836), of Carlisle, on July 29, 1818.[35][36] The couple had eleven children before Rebecca's abrupt death at age 43. Chamberlain remarried to Catharine Metzger, of Hanover, Pennsylvania, in 1845; they did not have children. One of Chamberlain's sons attended Oakland and graduated in 1851 but shortly after died of yellow fever.[36]

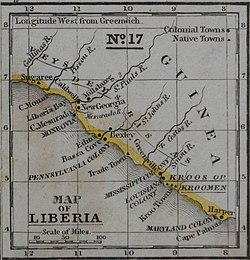

Chamberlain was opposed to slavery.[4] In the 1830s, he helped to create the Mississippi Colonization Society, an auxiliary of the American Colonization Society, whose goal was to send free people of color and freed slaves to the Mississippi-in-Africa colony, later annexed by the Colony of Liberia and now part of the modern-day Republic of Liberia. Others who were involved in founding the organization included the planters Isaac Ross, Edward McGehee, Stephen Duncan, and John Ker.[37]

Chamberlain received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from Centre in 1828.[38][39][f]

Death and legacy

[edit]

There are many details regarding Chamberlain's death, though some are conflicting. He was murdered at around 4:30 p.m. on September 5, 1851, at his home on Oakland's campus in Lorman by a planter named George Briscoe.[4][40] While Briscoe's exact motives are not known, sources agree that he arrived outside Chamberlain's house, perhaps drunk, and the men began to argue.[4][41] Briscoe proceeded to accuse Chamberlain of dishonesty and made other disparaging remarks before knocking Chamberlain to the ground by hitting him in the head with a whip. When Chamberlain stood, holding a piece of wood in an attempt to defend himself, Briscoe stabbed him in the chest with a Bowie knife.[41] Reports of the incident vary in the amount of time between the stabbing and Chamberlain's death; the Whig State Journal noted that his death was "almost instant",[42] though a contemporary biography by Dickinson College says he died in his wife's arms some "minutes later" and a contemporary report from The Port Gibson Herald and Correspondent specifies that he died in roughly fifteen minutes.[4][41] The latter source also claims that Chamberlain, after being stabbed, walked back into the house before collapsing to his knees and speaking his last words—"I am killed."[41] He was buried two days later in the Oakland College Cemetery; his first wife and four of their children are buried with him.[41][35] Briscoe, who fled the scene, died two days after the incident; officially, the cause of his death is unknown, but several contemporary and modern sources list it as a suicide.[43][4][7] Reported motives include Briscoe's general unhappiness with Chamberlain's anti-secession, anti-slavery views (alternatively Chamberlain's lack of support for "southern rights")[7][44] and the expulsion of a student, supposedly for giving a speech in favor of secession.[45] Some sources classified the murder as an assassination.[1][4]

Fate of Oakland College

[edit]

Immediately following Chamberlain's death, a minister and Oakland professor named John Russell Hutchinson became interim president.[46] It took roughly three months for a permanent successor, the minister Robert L. Stanton, to take the presidency, which he did in early November 1851.[47][g] Its next two presidents were James Purviance, a missionary and minister who resigned due to ill health in 1860,[48] and William L. Breckinridge, a minister who, like Chamberlain, later became president of Centre College.[49][50] The college closed in 1861 at the outbreak of the American Civil War. It reopened briefly after the war's end, under the leadership of president Joseph Calvin, though his death soon after quickly led to the school's permanent end.[31] In 1871, the campus was sold to the state, and Alcorn A&M College (now Alcorn State University) was opened as the first black land grant institution in the country.[4]

In 1879, Chamberlain-Hunt Academy opened in Port Gibson, Mississippi, under the auspices of the Synod of Mississippi. It was named for Chamberlain and David Hunt.[51] The academy functioned as a Presbyterian prep school—it became a military school in 1895—and was considered the de facto successor to Oakland.[51][7] The school closed in 2014 due to low enrollment, as it had fewer than thirty students during its last academic year.[52] Chamberlain's papers were originally housed by the academy before being moved to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson.[7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Norcross (1889)[9] and Nevin (1852)[10] differ from other sources in that they list Chamberlain's time in Bedford as having started in 1819 rather than 1818; Sprague (1857) says that Chamberlain "entered immediately upon his labors at Bedford" upon being offered the pastorate.[3]

- ^ A book published by Princeton Theological Seminary notes that Chamberlain founded three colleges and specifically names Centre as one of the three, though Chamberlain was only involved in the founding of Oakland College.[12] A 1994 history of Princeton Seminary by the professor and author David B. Calhoun also makes this claim.[13] It is incorrect, as Centre had been chartered in 1819,[14] several years before he was elected president in 1822.[7] Further, he was not among Centenary's founders; that school was chartered by the Louisiana State Legislature in 1825.[15]

- ^ Despite that McChord died before officially taking office, Centre recognizes him as its first president and Chamberlain as its second. Several sources opt to refer to Chamberlain as Centre's first president instead or use wording such as that used by Weston (2019), which says "The first actual president of the college was the Rev. Jeremiah Chamberlain."[17]

- ^ Sloane (2000) incorrectly spells his surname "Chamberlin" and includes a middle initial "C" that is unaccounted for in other sources.

- ^ Morgan (2008) claims he resigned March 7, 1829, after cost-cutting efforts from the board of trustees reduced his salary from $3,000 to $2,200 (equivalent to a reduction from $88,600 to $65,000 in 2024).[26] The overall consensus among sources is that he left in 1828 to open his own school. Voss (1923) claims Chamberlain resigned over disputes with the trustees as to the details of his ministerial obligations while president.[27]

- ^ Some sources claim he received this degree in 1825, during his term as president of Centre,[29] though contemporary newspaper reporting shows that he received a D.D. from Centre at the school's 1828 commencement and no sources list him as having received the same honorary degree from Centre twice.

- ^ Johnson & Brown (1904) incorrectly claim that Hutchinson was president from September 5, 1850 (a typo of Chamberlain's death date) until 1854 (the year Stanton resigned).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lippincott & Super 1886, p. 52.

- ^ Sprague 1857, p. 590.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sprague 1857, p. 591.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Jeremiah Chamberlain (1794–1851)". Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections. Dickinson College. 2005. Archived from the original on December 4, 2024. Retrieved May 12, 2025.

- ^ Lippincott & Super 1886, p. 65.

- ^ Gillett 1873, p. 381.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Jeremiah Chamberlain, Centre College President (1822–1826)". CentreCyclopedia. Centre College. Retrieved May 12, 2025.

- ^ Norcross 1889, pp. 289–291.

- ^ Norcross 1889, p. 291.

- ^ Nevin 1852, p. 298.

- ^ Gillett 1873, p. 429.

- ^ Centennial Celebration 1912, p. 411.

- ^ Calhoun 1994, p. 101.

- ^ a b "About Centre College: History". Centre College. Retrieved May 13, 2025.

- ^ Morgan 2008, p. 3.

- ^ "Presidents". CentreCyclopedia. Centre College. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2025.

- ^ Weston 2019, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Davidson 1847, p. 320.

- ^ Weston 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Weston 2019, p. 19.

- ^ Morgan 2008, p. 5.

- ^ a b "Untitled". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. December 4, 1826. p. 2. Retrieved May 13, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weston 2019, p. 23.

- ^ a b Sloane 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Sloane 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Morgan 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b Voss 1923, p. 21.

- ^ Morgan 2008, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Sprague 1857, p. 592.

- ^ Cotton, Gordon (January 26, 2020). "Bethel, Bruinsburg and Burr: little-known history in Claiborne County". Vicksburg Daily News. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Gillis 1891, p. 310.

- ^ Waugh, Barry (April 6, 2021). "S. Beach Jones, 1811–1883, Presbytery of Patapsco". Presbyterians of the Past. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- ^ Sansing 1990, p. 21.

- ^ "Untitled". Vicksburg Whig. Vicksburg, Mississippi. April 17, 1850. p. 1. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Sanders 2014, p. 11.

- ^ a b Sprague 1857, p. 593.

- ^ Miller 2010, pp. 53–54.

- ^ "Untitled". Vermont Chronicle. Bellows Falls, Vermont. August 15, 1828. p. 3. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cornelius & Edwards 1827, pp. 134–135.

- ^ "The late tragedy in Mississippi". New York Daily Herald. New York, New York. September 27, 1851. p. 7. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "A horrid tragedy!". The Port Gibson Herald and Correspondent. Port Gibson, Mississippi. September 12, 1851. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- ^ "Dreadful tragedy". Whig State Journal. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. September 30, 1851. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Untitled". The Springfield Daily Republican. Springfield, Massachusetts. September 13, 1851. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nguyen, Julia Houston (July 11, 2017). "Oakland College". The Mississippi Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- ^ Sansing 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Johnson & Brown 1904, p. 496.

- ^ "Untitled". The Primitive Republican. Columbus, Mississippi. November 6, 1851. p. 3. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rev. Dr. James Purviance". The Central Presbyterian. Richmond, Virginia. July 5, 1871. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Religious intelligence: church and ministry". The Springfield Daily Republican. Springfield, Massachusetts. February 4, 1860. p. 1. Retrieved May 14, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weston 2019, p. 41.

- ^ a b Rogal 2009, p. 163.

- ^ "Chamberlain Hunt Academy to close". The Vicksburg Post. July 29, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Calhoun, David B. (1994). Princeton Seminary, Volume I: Faith and Learning, 1812–1868. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust. ISBN 085151670X – via Internet Archive.

- The Centennial Celebration of the Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America at Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University. 1912 – via Internet Archive.

- Cornelius, Elias; Edwards, Bela Bates (1827). Quarterly Register and Journal of the American Education Society. Vol. 1. Andover, Massachusetts: Flagg and Gould – via Internet Archive.

- Davidson, Robert (1847). History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Kentucky, with a Preliminary Sketch of the Churches in the Valley of Virginia. New York, New York: R. Carter & Brothers – via Internet Archive.

- Gillett, Ezra Hall (1873). History of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work – via Internet Archive.

- Gillis, Norman E. (1891). Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi. Vol. 2, part 2. Chicago, Illinois: Goodspeed Publishing. OCLC 1518470369 – via Google Books.

- Johnson, Rossiter; Brown, John Howard, eds. (1904). The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans. Vol. 5. Boston, Massachusetts: The Biographical Society – via Internet Archive.

- Lippincott, J. B.; Super, O. B. (1886). Alumni Record of Dickinson College. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Press of Central Pennsylvania – via Internet Archive.

- Miller, Mary Carol (2010). Lost Mansions of Mississippi. Vol. 2. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604737868 – via Google Books.

- Morgan, Lee (2008). Centenary College of Louisiana, 1825–2000: The Biography of an American Academy. Shreveport, Louisiana: Centenary College of Louisiana. ISBN 9780979323096. OCLC 288447398 – via Internet Archive.

- Nevin, Alfred (1852). Churches of the Valley, or, an Historical Sketch of the Old Presbyterian Congregations of Cumberland and Franklin Counties, in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. M. Wilson – via Internet Archive.

- Norcross, George (1889). The Centennial Memorial of the Presbytery of Carlisle. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Meyers Printing and Publishing House – via Internet Archive.

- Rogal, Samuel J. (2009). The American Pre-College Military School: a History and Comprehensive Catalog of Institutions. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786439584 – via Google Books.

- Sanders, William L. (2014). Carved in Stone: Cemeteries of Claiborne County, Mississippi. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Dorrance Publishing Company. ISBN 9781480908833 – via Google Books.

- Sansing, David G. (1990). Making Haste Slowly: The Troubled History of Higher Education in Mississippi. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604732702 – via Google Books.

- Sloane, Bentley (2000). 175 Years, Centenary College, 1825–2000: a Brief History of Centenary College of Louisiana. Shreveport, Louisiana: Centenary College of Louisiana – via Internet Archive.

- Sprague, William Buell (1857). Annals of the American Pulpit, or, Commemorative Notices of Distinguished American Clergymen of the Various Denominations. New York, New York: R. Carter – via Internet Archive.

- Voss, Louis (1923). The Beginnings of Presbyterianism in the Southwest. New Orleans, Louisiana: Presbyterian Board of Publications of the Synod of Louisiana – via Google Books.

- Weston, William (2019). Centre College: a Bicentennial History, 1819–2019. Danville, Kentucky: Centre College. ISBN 9781694358639. OCLC 1142930784.

- 1794 births

- 1851 deaths

- People from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

- People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania

- People from Jefferson County, Mississippi

- Dickinson College alumni

- Princeton Theological Seminary alumni

- Centre College faculty

- Centenary College of Louisiana faculty

- American Presbyterian ministers

- American abolitionists

- American murder victims

- People murdered in Mississippi

- People of the American colonization movement

- Presbyterian abolitionists

- Presidents of Centre College

- Presidents of Oakland College (Mississippi)

- Presidents of Centenary College of Louisiana

- 19th-century American Presbyterian ministers

- American slave owners

- People murdered in 1851

- Deaths by stabbing in Mississippi