Islamic Centre Hamburg

| Imam Ali Mosque | |

|---|---|

Imam-Ali-Moschee مسجد امام علی Masjed-e Emām ʿAlī | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shia Islam (former) |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Mosque (1966–2024) |

| Status | Forced closure |

| Location | |

| Location | Uhlenhorst, Hamburg |

| Country | Germany |

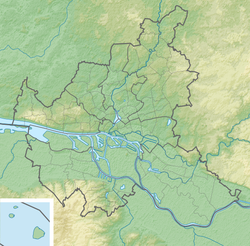

Location of the closed mosque in Hamburg | |

| Geographic coordinates | 53°34′28.45″N 10°00′30.30″E / 53.5745694°N 10.0084167°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Architekturbüro Schramm und Elingius; Parviz Zargarpour; Gustav Lüttge |

| Type | Mosque architecture |

| Completed | 1966 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 1,500 worshippers |

| Dome(s) | 2 |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

| Minaret height | 16 m (52 ft) |

| Website | |

| izhamburg | |

The Islamic Centre Hamburg (German: Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg, IZH; Persian: مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ, romanized: Markaz-e Eslāmī-ye Hambūrg), was the proprietor organisation of the Imam Ali Mosque (German: Imam-Ali-Moschee)[1] also known as the Blue Mosque (German: Blaue Moschee),[2] the oldest mosque in Hamburg, Germany. It was established in the late 1950s by a group of Iranian emigrants and construction was completed in the early 1960s. The IZH served both as a place of worship and of inner- and inter-religious dialogue. It was generally considered to be aligned with the government of Iran, both during the Shah's reign and later following the 1979 Iranian Revolution.[3] Amid investigations into these latter ties, the Federal Ministry of the Interior and the Homeland deemed the IZH to be unconstitutional in July 2024, leading to the mosque’s closure and the building being placed under the ministry’s administration.[4] The IZH challenged the decision in the Federal Administrative Court. As of July 2025, the case remains pending, and until the court rules on the legality of the closure and the federal takeover of the building, it cannot be repurposed or reopened.[5]

History

[edit]Hamburg as Germany's main harbor city has been a trading hub throughout the nation's history. It therefore attracting many immigrants, including a large number of carpet traders from Iran. During a meeting at the Atlantic Hotel in 1953, a group of Iranian residents of Germany discussed the need to establish their own religious center. They elected a board of nine community members[a] to lead the organisation set to be established to realize this undertaking.[6][7] Thereafter an Iranian carpet trader registered a non-profit organisation for the purpose of constructing a Shiite mosque.[3][8] Simultaneously another group of Iranian carpet traders began to collect money for the construction of a mosque in Hamburg at the suggestion of Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Husayn Borujerdi.[6] Later, a letter was sent to Husayn Borujerdi and other prominent leaders in Iran asking them for help; Borujerdi agreed to help and donated RI100,000 for the mosque.[9] Additionally, Borujerdi insisted that no financial aid from the German government or German NGOs was to be accepted for the mosque. This led him to have to shoulder the vast majority of the cost. He received financial support of RI300,000 from the Iranian Endowments Administration and more support from the Iranian community in Hamburg, leading to the local name the Iranians' Mosque for the building.[10] These funds were still insufficient for financing the mosque's construction. Therefore a loan was taken out from a bank in Hamburg to finance the project, but remittances from Iran came in lower than expected leading to the bank demanding repayment at once.[10] These financial troubles impeded the building effort and were only able to be resolved by a new RI1 rial tax on sugar levied by the Tehran Chamber of Commerce. This made it possible to repay the entire 400,000 Deutsche Marks still owed to the bank in 1964.[11]

Architecture and construction

[edit]Following a public design competition, Hosein Lorzade chose for Husayn Borujerdi an entry by Architekturbüro Schramm und Elingius with cooperation from an Iranian engineer named Parviz Zargarpour, which sought to combine eastern and western architecture.[6][12][13][14] Gustav Lüttge was tasked as the landscape architect for the garden and fountain. The entire architectural ensemble of the mosque, its garden, fountain and fence is protected as cultural property by law.[15][16][17]

-

Mosque exterior with courtyard and fountain

-

Prayer room inside the mosque

-

Islamic library entrance

Local authorities in Hamburg initially opposed the construction of a mosque, particularly as the plot chosen by the committee was zoned as green space.[10] Additionally, building codes made the extravagant blue exterior difficult to realize. These issues were however resolved due to political goodwill by Paul Nevermann and Kurt Braasch towards the Iranian community.[18] This change of opinion in the city government can largley be attributed to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's intervention on behalf of the Iranian community in Hamburg related to his upcoming 1967 state visit.[19] Construction eventually began once the organization's first director, Ayatollah Mohagheghi, arrived in Hamburg. The building's cornerstone was laid by Mohagheghi at the Shah's request on 13 February 1961. In 1963, Mohagheghi's return to Iran due to the aforementioned financial troubles halting construction.[19] It resumed in 1964 and in 1966 most of the mosque's tile work was finished under the supervision of Mohammad Bagher Ansari and financed by private donations from Hamburg and Tehran. The mosque officially opened on 8 February 1966.[20]

Inner- and inter-religious relations

[edit]

Mohammad Beheshti reported early experiences of religious discrimination in Germany, for example being arrested as a "sorcerer" for praying in Frankfurt Airport. He was aware of his negative perception by the German public and tried to encourage the use of "Muslim" when referring to the adherents of Islam instead of Mohammedan.[21][22] Additionally, when a German newspaper called the newly founded Islamic Republic a "dictatorial regime of clergy" Beheshti perceived it as a mischaracterisation. Therefore, he published a German booklet via the IZH in defense of the new Islamic system of government, even a decade after his tenure in Germany had ended.[10] However, his successor Mohammad Mojtahed Shabestari inversely became a political activist and anti-Islamic-Republic cleric in Iran.[23]

Beheshti also initiated a tradition of inter-religious academic dialogue in the IZH.[24] The IZH hosted a number of notable intellectual and religious figures[b] since. While its German and Persian language outreach was primarily organized by Shiites, its Arabic language activities were largely carried out by Sunni Muslim members of the Muslim Brotherhood. This led to large numbers of Sunni Muslims attending the mosque. They often responded to Quranic recitations by saying "Ameen", which caused some Shiite extremists to denounce the mosque as having been "turned Sunni".[25]

From its inception the site had primarily been focused on providing Muslims and non-Muslims in particular with scholarly information about Islam, without trying to proselytize. For this purpose the mosque allowed visitors at all events and had informed personnel on staff during all opening hours willing to answer the public's questions.[26] Additionally, the site annually participated in Open Mosque Day and in 2022 began Islam Week to inform outsiders about their beliefs.[27][26] The site's multilingual library, as well as its youth library, were open to the general public but only members of the organisation were allowed to borrow books.[28]

The then-head of the Senate Chancellery of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, Christoph Krupp, spoke favorably about the mosque's efforts of inner- and inter-religious dialogue and called it a "successful model" for an Islamic cultural center that should be imitated.[29]

Islamic studies professor Katajun Amirpur said that many of the IZH's efforts towards religious influence on Shiites in Germany came down to its willingness to fund their communities. She was unable to quantify how successful these efforts were but noted that a significant minority of religious Shiites in Germany are opposed to the Islamic Republic and therefore unreceptive to such efforts.[30]

Controversy and closure

[edit]From 1993 until its forced closure, the State Office for the Protection of the Constitution of Hamburg monitored the IZH due to its ideological, organisational, and personal ties to the Iranian government. The IZH repeatedly protested against its monitoring, stating that it was a "purely religious institution that, independent of Tehran, only deals with the religious affairs of Shiite Muslims living in Europe."[2] A particular point of focus was support for the fatwa against Salman Rushdie in IZH related circles and related positions which were seen to support Islamic terrorism.[31][32] Moghaddam, the then-director of the IZH, did not deny the IZH being composed of supporters of the Islamic Revolution and being pro-Iranian in its positions, but did deny being directed by Iran or supporting terrorism (however admitting mistakes in their handling of the Salman Rushdie affair).[33]

Germany's growing constitutionality concerns

[edit]From 1996 to 2004 the IZH was an official organizer of the annual Qods Day demonstration in Berlin, a controversial day of remembrance and protest first proclaimed by Ruhollah Khomeini. In 2010 the IZH again publicly advertised the event.[34][35] In 2016 around 200 IZH congregants attended the event. The event was seen as inherently anti-constitution, anti-democratic and anti-semitic by the State Office of for the Protection of the Constitution of Hamburg.[36]

On 17 June 2022, IZH deputy director Seyed Soliman Mousavifar received an expulsion order from the Federal Ministry of the Interior and the Homeland after an investigation revealed that he maintained ties with Hezbollah representatives in Lebanon.[37] Mousavifar appealed the decision twice, but was rejected by the Hamburg Administrative Court and left the country in November the same year.[38][39]

During the Mahsa Amini protests, a motion was passed by the Bundestag, which among other things, called on the German government to "examine whether and how the [IZH] can be closed as a hub for the Iranian regime's operations in Germany."[40] More calls for the IZH's closure were made after the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel, with Greens member Jennifer Jasberg stating "We do not want to accept that individual actors in our city create a breeding ground for hatred against Israel".[41]

In 2024 the State Office for the Protection of the Constitution of Hamburg expressed concerns about Iftar celebrations at the mosque. The centre had invited local civic leaders in one of its outreach initiatives. The state office believed the entire event to be anti-constitution and feared it might be used express anti-Israel sentiments.[42]

IZH's growing frustrations with perceived Islamophobia

[edit]In the 1990s IZH was the organisational lynchpin in protest activities in Mainz against a dormitory and training facility run by the anti-Islamic-Republic Shia-Islamist party and then-paramilitary organisation, MEK. The IZH alleged that the MEK repeatedly tried to infiltrate circles close to the center, falsely portrayed the centre's worshippers as "henchmen" of the Islamic Republic, and threatened and harassed worshippers and their families. The protests led to a handful of arrests of protesting students—who according to Moghaddam for six months were only allowed to be visited in prison by him and the Iranian ambassador, Nawab. Some of them were deported following their prison stay, while the others were given parole. Moghaddam judged this punishment, and the preceding police violence to have been unjust and motivated by bigotry.[43]

On 24 July 2021 the mosque was the victim of a politically motivated attack related to the 2021–2022 Iranian protests. The mosque's exterior was covered with red paint and Persian-language political slogans such as "Shame on Islam", "Death to the Islamic Republic", and "Movement for water [for Khuzestan province] and blood [of the Ayatollahs]". The IZH complained that the attack had been caused by the German government's narratives about the centre and saw it as evidence of growing Islamophobic sentiments in Germany and judged the incident to have been a religiously motivated hate crime. This view was deemed to be in conflict with the German constitution by the State Office for the Protection of the Constitution of Hamburg.[44][45][46]

In September 2022 another attack on the mosque occurred, a man pretending to be a delivery driver wearing a fake mustache and a wig entered the building and spread red paint all throughout the foyer, he then assaulted and injured a 71-year old man trying to stop him before fleeing the scene.[47][48]

Police raid and ministry seizure of the mosque

[edit]

The centre was raided on 24 July 2024 and the organisation dissolved by order of Germany's minister of the interior and the homeland Nancy Faeser, who claimed that it was being used by the Iranian government to "propagate an Islamist, totalitarian ideology" in a press release.[4][49] The actual legal reasoning alleges the centre was fundamentally constituted against Germany's constitutional order, against "the thought of international understanding", and against German criminal statutes, ie all three possible legal reasons for the government to force the dissolution of a registered organisation. They additionally state the IZH to "run counter to Germany’s obligations under international law" and "to promote efforts outside the country [...] which are incompatible with the fundamental values of a state order that respects human dignity".[50][51][52] Documents provided to Der Spiegel stated that the mosque's director had reportedly received orders from Mehdi Mostafavi,[53][54] former advisor to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[55] Several other affiliated Islamic centres were closed down as well, including the Centre for Islamic Culture Frankfurt and the Islamic Centre Berlin.[56]

Reactions

[edit]Soon after the raid, Germany's ambassador to Iran was summoned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[57] The ban was strongly condemned by Iran, with several government agencies accusing the German government of Islamophobia.[58][59] Religious authorities shared similar sentiments, with Qom Seminary administrators claiming that "the move was reminiscent of the racist policies of the Nazi regime" and would "expose the hypocrisy of those claiming to uphold freedom of religion and expression."[60] The Parliamentary Union of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation Member States strongly condemned the closure, saying it constituted a violation of human rights, particularly freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and freedom of assembly—in addition to being a violation of the UN Charter. It stated the move would increase "tension, hatred, Islamophobia and violence against Muslims" in Germany and called for an immediate reversal.[61] The American Jewish Committee lauded the raid and closure. Additionally, it took credit for publicly raising the alarms about the centre's alleged "misuse" and personally thanked minister Nancy Faeser for the raid and closure.[62] The National Council of Resistance of Iran, led by the Shia-Islamist group MEK, praised the raid and closure but considered it belated. They additionally stressed to have worked against the IZH, trying to bring about its closure "for four decades".[63]

There have been more than 90 demonstrations (mostly in connection with a Friday prayer) against the ministry's actions in front of the site; with around 120 people attending them regularly.[64][65][66] The property's neighbours expressed particular displeasure with the city's and ministry's unwillingness to empty trash containers on the site since the raid leading to significant fetid odor development. Other complaints were related to witnessing the mosque's alarm systems often being triggered at night, people turning on all the lights and leaving them running around the clock, the handling of demonstrations near the site and no one feeling responsible for or being available to talk to regarding these issues.[67][68]

Legal challenge of the ban

[edit]Motions by the two IZH-aligned organisations in Berlin and Frankfurt for a provisional remedy were denied by the Federal Constitutional Court in February and March 2025,[69][70] meaning their closure will remain in effect and the former mosque will remain under the administration of the Federal Ministry of the Interior until the main trial at the Federal Administrative Court has taken place and it has been determined whether the closure was lawful and whether the building was rightfully taken over by the ministry. The IZH has not sought provisional remedies and is instead waiting solely for the main trial.[64]

Directors

[edit]- Hojjatulislam Mohagheghi (1953–1963)[71]

- Hojjatulislam Mohammad Beheshti (1963–1970)

- Hojjatulislam Mohammad Mojtahed Shabestari (1970–1978)

- Hojjatulislam Mohammad Khatami (1978–1980)

- Hojjatulislam Mohammad Reza Moghaddam (1980–1992)

- Hojjatulislam Mohammad Bagher Ansari (1992–1998)

- Hojjatulislam Reza Hosseini Nassab (1999–2003)

- Hojjatulislam Seyyed Abbas Hosseini Ghaemmaghami (2004–2009)

- Hojjatulislam Reza Ramezani Gilani (2009–2018)[72][73]

- Hojjatulislam Mohammad Hadi Mofatteh (2018–2024)[74]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kraft, Sabine. Islamische Sakralarchitektur in Deutschland [Islamic sacred architecture in Germany]. p. 91.

- ^ a b "Neue Erkenntnisse über das Islamische Zentrum Hamburg" [New findings about the Islamic Center Hamburg]. hamburg.de (in German). Archived from the original on 17 April 2024. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Thomas (2003). Moscheen in Deutschland Konflikte um ihre Errichtung und Nutzung [Mosques in Germany Conflicts Surrounding their Construction and Use] (PDF). Forschungen zur deutschen Landeskunde (in German). Vol. 252. Flensburg: Deutsche Akademie für Landeskunde. p. 51. ISBN 3-88143-073-3.

- ^ a b Jaeger, Mona; Staib, Julian (24 July 2024). "Blaue Moschee: Faeser verbietet Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg" [Blue Mosque: Faeser bans Islamic Center Hamburg]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Drügemöller, Lotta (25 July 2025). "Zukunft der Blauen Moschee in Hamburg: Schiit*innen wollen wieder drinnen beten". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ a b c سایت, مدیر (15 November 2014). "آشنایی با مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ". مؤسسه بين المللی المرتضی (ع) (in Persian). Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Tārīkhche-ye Masjed va Markaz-e Eslāmī-ye Hāmburg تاریخچه مسجد و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [History of the Mosque and Islamic Center of Hamburg] (in Persian). June 1995. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Mediengruppe, FUNKE (24 March 2015). "Hamburgs bekannteste Moschee an der Alster". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "Mosāhebe bā Āyatollāh Abbās Qā'em Maqāmi" مصاحبه با آیتالله عباس قائم مقامی [Interview with Āyatollāh Abbās Qā’em Maqāmi]. Islamic Revolution Document Center Archives (in Persian). Tehran.

- ^ a b c d "Mosāhebeh bā Āyatollāh Seyyed Hādi Khosrowshāhi" مصاحبه با آیتالله سید هادی خسروشاهی [Interview with Āyatollāh Seyyed Hādi Khosrowshāhi]. Islamic Revolution Document Center Archives (in Persian). Tehran.

- ^ Torabi, Hamid-Reza. Masjed-e Âbi-ye Âlmân: Tārikh-e Masjed-e Emām ʿAlī (ʿa) va Markaz-e Eslāmi-ye Hāmburg حمیدرضا ترابی، مسجد آبی آلمان: تاریخ مسجد امام علی(ع) و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [Germany's Blue Mosque: History of the Imam Ali Mosque and the Islamic Center Hamburg] (in Persian). p. 91.

- ^ Tārīkhche-ye Masjed va Markaz-e Eslāmī-ye Hāmburg تاریخچه مسجد و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [History of the Mosque and Islamic Center of Hamburg] (in Persian). June 1995. pp. 9–10.

- ^ "Mosāhebe bā Mohammad Bāqer Ansāri" مصاحبه با محمد باقر انصاری [Interview with Mohammad Bāqer Ansāri]. Islamic Revolution Document Center Archive. Tehran.

- ^ Bartetzko (25 July 2024). "Plötzlich Denkmaleigner". moderneREGIONAL (in German). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Denkmalliste nach § 6 Absatz 1 Hamburgisches Denkmalschutzgesetz.

- ^ Bartetzko (25 July 2024). "Plötzlich Denkmaleigner". moderneREGIONAL (in German). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Laurustico - Club für Gartenfreunde | Gartenevents in Hamburg - Persischer Garten der Imam Ali Moschee". www.laurustico.de. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Torabi, Hamid-Reza. Masjed-e Âbi-ye Âlmân: Tārikh-e Masjed-e Emām ʿAlī (ʿa) va Markaz-e Eslāmi-ye Hāmburg حمیدرضا ترابی، مسجد آبی آلمان: تاریخ مسجد امام علی(ع) و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [Germany's Blue Mosque: History of the Imam Ali Mosque and the Islamic Center Hamburg] (in Persian). p. 91.

- ^ a b "Mosāhebeh bā Hojjat al-Eslām Maʿādīkhvāh" مصاحبه با حجتالاسلام معادیخواه [Interview with Hojjat al-Eslām Maʿādīkhvāh]. Islamic Revolution Document Center Archives (in Persian). Tehran.

- ^ Tārīkhche-ye Masjed va Markaz-e Eslāmī-ye Hāmburg تاریخچه مسجد و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [History of the Mosque and Islamic Center of Hamburg] (in Persian). June 1995. p. 12.

- ^ Sarabandi, Mohammad-Reza (2008). Zendegī va Mobārezāt-e Āyatollāh Shahīd Doḵtor Seyyed Moḥammad Ḥoseynī Beheštī be Revāyat-e Asnād زندگی و مبارزات آیتالله شهید دکتر سید محمد حسینی بهشتی به روایت اسناد [Life and Struggles of Ayatollah Martyr Dr. Seyyed Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti According to Documents] (in Persian). Tehran: Islamic Revolution Document Center Archives. p. 60.

- ^ «Bī-eʿtenā be Qodrat», goft-o-gū bā Doḵtor Javād Azhāʾī «بیاعتنا به قدرت» گفتوگو با دکتر جواد اژهای. Hamshahri Mah (in Persian). Vol. 6. Tehran: “Indifferent to Power,” interview with Dr. Javad Azhāʾi. May–June 2005.

- ^ "Iran Primer: Politics and the Clergy". PBS.

- ^ Bāzshenāsī-ye Yek Andīsheh: Yādnāmeh-ye Bistomin Sālgard-e Shahādat-e Āyatollāh Doḵtor Beheštī بازشناسی یک اندیشه: یادنامه بیستمین سالگرد شهادت آیتالله دکتر بهشتی [Rediscovering a Thought: Memorial Book for the Twentieth Anniversary of the Martyrdom of Ayatollah Dr. Beheshti]. Tehran: Boq‘eh. 2001. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Torabi, Hamid-Reza. Masjed-e Âbi-ye Âlmân: Tārikh-e Masjed-e Emām ʿAlī (ʿa) va Markaz-e Eslāmi-ye Hāmburg حمیدرضا ترابی، مسجد آبی آلمان: تاریخ مسجد امام علی(ع) و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [Germany's Blue Mosque: History of the Imam Ali Mosque and the Islamic Center Hamburg] (in Persian). p. 128.

- ^ a b "Moṣāḥebe bā Ḥojjat ol-Eslām Moḥammad Kāẓem Shāhābādī" مصاحبه با حجتالاسلام محمد [Interview with Hojjat al-Islam Mohammad Kazem Shah-Abadi]. Islamic Revolution Document Center Archives (in Persian). Tehran.

- ^ Weber, Kaja (3 October 2022). "Moschee: Erste Islamwoche in Hamburg startet am Montag". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ kirchner (20 October 2018). "Islamische Fachbibliothek - Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg e.V. - Bibliotheken in Hamburg". Hamburg Magazin (in German). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Torabi, Hamid-Reza (2015). Masjed-e Âbi-ye Âlmân: Tārikh-e Masjed-e Emām ʿAlī (ʿa) va Markaz-e Eslāmi-ye Hāmburg حمیدرضا ترابی، مسجد آبی آلمان: تاریخ مسجد امام علی(ع) و مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ [Germany's Blue Mosque: History of the Imam Ali Mosque and the Islamic Center Hamburg] (in Persian). p. 252.

- ^ deutschlandfunk.de (25 July 2024). "Wie das IZH schiitische Gemeinden in Deutschland beeinflusste". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Grünewald, Klaus (1995). "Defending Germany's Constitution". Middle East Forum.

- ^ "Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg: Die Problem-Moschee - WELT". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Gozāresh va Taḥqīq: «Āshenāʾī bā Markaz-e Eslāmī-ye Hāmburg»" گزارش و تحقیق: آشنایی با مرکز اسلامی هامبورگ»، [Report and Research: “Familiarity with the Islamic Centre of Hamburg”]. Nāmeh-ye Farhang (in Persian) (8): 131. Summer 1992.

- ^ "Verfassungsschutzbericht 2009". www.hamburg.de. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Verfassungsschutzbericht 2010" (PDF). www.hamburg.de. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Balasko, Sascha (12 July 2016). "Was geht in der Blauen Moschee mit Islamisten vor?". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Germany Expels Iranian Cleric Over Support For Shiite Extremists". Iran International. 19 June 2022. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ ""Hat in Deutschland nichts zu suchen": Vize-Mullah hat Hamburg verlassen" [“Has no business in Germany”: Vice Mullah has left Hamburg]. Focus (in German). 7 November 2022. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Ekrutt, Joana (5 November 2022). "Blaue Moschee Hamburg: IZH-Vize entgeht Abschiebung – SPD fordert Schura-Ausschluss" [Blue Mosque Hamburg: IZH vice president escapes deportation – SPD calls for Shura exclusion]. Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Bundestag fordert Verbot des Islamischen Zentrums Hamburg" [Bundestag calls for ban on the Islamic Center Hamburg]. Der Spiegel (in German). 9 November 2022. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 9 November 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Hamburgs SPD, Grüne, CDU und FDP fordern Schließung des IZH" [Hamburg's SPD, Greens, CDU and FDP demand closure of the IZH]. Norddeutscher Rundfunk (in German). 25 October 2023. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Außenposten des Mullah-Regimes: Extremistisches Islamisches Zentrum lädt Abgeordnete zum Ramadanfest ein - WELT". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Moṣāḥebe bā Ḥojjat al-Eslām Moḥammad Moqaddam" مصاحبه با حجتالاسلام محمد مقدم [Interview with Hojjat al-Islam Mohammad Moghaddam]. Islamic Revolution Document Center Archives. 30 June 1996.

- ^ "Verfassungsschutzbericht 2021" (PDF). www.hamburg.de. p. 51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Gaertner, Rüdiger; Ebner; image001-3 (25 July 2021). "Farbanschlag: Bedrohliche Zeichen auf Hamburger Moschee". MOPO (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Knödler, Gernot (26 July 2021). "Farbanschlag auf Blaue Moschee". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Knödler, Gernot (26 July 2021). "Farbanschlag auf Blaue Moschee". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Jäckel, Catharina (26 September 2022). "Polizei Hamburg: Farbanschlag auf Islamisches Zentrum – 71-Jähriger verletzt". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Germany shuts down Islamic Center Hamburg". DW News. 24 July 2024. Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Bekanntmachung eines Vereinsverbots gegen die Vereinigung Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg e.V. (IZH)

- ^ Siemens, Ansgar; Wiedmann-Schmidt, Wolf (24 July 2024). "Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg: Faeser verbietet Trägerverein der »Blauen Moschee«". Der Spiegel (in German). ISSN 2195-1349. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ red, ORF at/Agenturen (24 July 2024). "Deutschland: Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg verboten". religion.ORF.at (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "German mosque took orders from Iran, aided Hezbollah before closure - report". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Reuters. 11 August 2024. Archived from the original on 12 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Head of banned German mosque received orders from Iranian official, report says". The Times of Israel. Reuters. 11 August 2024. Archived from the original on 12 August 2024. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ Sahimi, Muhammad (2 January 2011). "Ahmadinejad Fires 14 Advisers in Major Shake-up". PBS. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Bekanntmachung eines Vereinsverbots gegen die Vereinigung Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg e.V. (IZH)" [Announcement of a ban on the association Islamic Center Hamburg e.V. (IZH)] (PDF). Bundesanzeiger (in German). 24 July 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Wegen Verbots des IZH: Teheran bestellt deutschen Botschafter nach Razzia in Blauer Moschee ein" [Because of ban on IZH: Tehran summons German ambassador after raid on Blue Mosque]. Der Spiegel (in German). 24 July 2024. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Iran condemns Germany's closure of Islamic Center Hamburg". Middle East Monitor. 28 July 2024. Archived from the original on 28 July 2024. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Iran's ICRO condemns closure of Islamic Center Hamburg". Islamic Republic News Agency. 27 July 2024. Archived from the original on 27 July 2024. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Iran seminaries condemn Germany's closure of Islamic centers". Mehr News Agency. 28 July 2024. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "PUIC Secretary General Denounces the Closure of Islamic Centres by the German Authorities". | PUIC (in Arabic). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "AJC Welcomes Ban on Activities of Iranian Outpost in Hamburg, Calls for Comprehensive Strategy Against Iranian Threats | AJC". www.ajc.org. 24 July 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Iran (NCRI), Secretariat of the National Council of Resistance of (24 July 2024). "Closure Of Regime Centers In Germany Is A Belated But Necessary Action". NCRI. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ a b Drügemöller, Lotta (25 July 2025). "Zukunft der Blauen Moschee in Hamburg: Schiit*innen wollen wieder drinnen beten". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Berner, Dominic (22 August 2024). "Blaue Moschee: Widerstand gegen Demos in Hamburg – „IZH bleibt geschlossen!"". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ dpa (16 August 2024). "Freitagsgebet: Freitagsgebet vor geschlossener Blauer Moschee". Die Zeit (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Ulrich, Friederike (30 July 2024). "Blaue Moschee in Hamburg: Nachbarn klagen über Ungeziefer und Gestank". www.abendblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Drügemöller, Lotta (2 August 2024). "Zukunft der Blauen Moschee in Hamburg: Die Freiheit der Andersgläubigen". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "BVerwG 6 VR 2.24, Beschluss vom 26. Februar 2025 | Bundesverwaltungsgericht". www.bverwg.de. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "BVerwG 6 VR 4.24, Beschluss vom 04. März 2025 | Bundesverwaltungsgericht". www.bverwg.de. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "Building history of Islamic Centre Hamburg". Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Direction of ICH". Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Ayatollah Ramezani's mission in Hamburg ends". Tehran Times. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Neuer Leiter des Islamischen Zentrums ist dialogbereit" [New head of the Islamic Center is ready for dialogue]. Die Welt (in German). 31 August 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Their names were: Haj Ali Naqi Kashani (1st chairman), Hossein Valadi, Ali Mohammad Baqerzadeh, Mohammad Taqi Tabarak, Mohammad Khosroshahi, Hamid Shojaei, Abdol-Ali Feyz, Mohammad Hossein Dehdashti, and Mir Hossein Ghaffari.

- ^ Among them: Jean-Loup Herbert , Annemarie Schimmel, Claude Fischler, Roger Garaudy, Issam al-Attar, Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah, Mohammad Mehdi Shamseddine, Kalim Siddiqui, and Necmettin Erbakan.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in German) Archived 30 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Official website (in English)

- A brief history, Hamburg Islamic Center.

- 1966 establishments in West Germany

- 2024 disestablishments in Germany

- 20th-century mosques in Europe

- Anti-Israeli sentiment in Europe

- Anti-Israeli sentiment in Iran

- Anti-Islam sentiment in Germany

- Buildings and structures in Hamburg-Nord

- Former mosques in Germany

- Iranian organizations based in Germany

- Iranian propaganda organisations

- Mosques completed in 1966

- Mosques in Hamburg

- Mosque buildings with domes in Germany

- Shia mosques in Europe

- Mosque buildings with minarets in Germany

- Germany–Iran relations

- Religious organizations established in the 1950s

- Heritage sites in Hamburg

- Shia Islam in Germany

- Terrorism in Germany

- Hate crimes in Europe