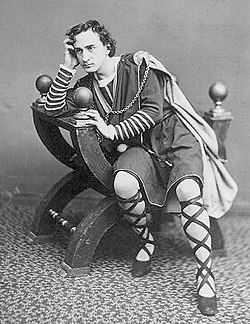

Ida Vernon

Ida Vernon | |

|---|---|

Ida Vernon c.1880-1885 | |

| Born | Isabella MacGowan September 4, 1843 At sea |

| Died | February 22, 1923 (aged 79) New York City, U.S. |

| Other names | I. V. Taylor, Isabella Ida Vernon Taylor |

| Occupation | Stage actress |

| Years active | 1856-1917 |

| Known for | The Two Orphans, The Man from Home |

| Spouse |

|

| Signature | |

Ida Vernon (September 4, 1843 – February 22, 1923), was the stage name of a naturalized American actress of Scottish-Canadian origin, who began acting at age 12 in 1856, and finished up her career in 1917. During her sixty-one years in the theater she played opposite many of the most famous actors of the American stage, including Edwin Booth, to whom she was twice engaged. She managed a Richmond theatre during the American Civil War, and was twice imprisoned by Union authorities for blockade running during the conflict. Her most enduring character was that of Sister Genevieve, which she created for the 1874 American debut of The Two Orphans. While performing that role on December 5, 1876, she narrowly escaped the Brooklyn Theatre fire that killed over 275 people. Vernon was the original Lady Bracknell in the American premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest. Later in her career she played an important supporting part in The Man from Home (1907), which ran for 500 performances on Broadway.

Early life

[edit]She was born on September 4, 1843,[1] to parents from Scotland.[2] According to Vernon, she was born at sea on a British ship carrying her mother to Canada to join her father, a British Army officer who was posted there. Vernon said "I lived at home in the Canadian military stations until my sister and I were sent to the convent in Montreal.[fn 1] There I was expected to recite poems to visitors. That is why the Sisters called me 'the little actress'. Two years later, when I was twelve, I learned what the term meant."[3]

Vernon's parents had moved to New York; while visiting them on Christmas vacation, she was taken to see Uncle Tom's Cabin at the Chatham Theatre, and decided to become an actress. She persuaded her father and brother to call upon actor-manager Thomas Barry at his hotel, who convinced them the best way to discourage acting ambition was to allow her to try it.[3]

Stage name controversy

[edit]"Ida Vernon" is a stage name; from different sources it is known that her first name was Isabella,[1] and her surname MacGowan.[4] There is no known public statement by either Ida Vernon or the journalists who interviewed and wrote about her, that her name was Isabella MacGowan. Vernon, though she spoke of her parents, an older brother, and a sister in interviews, did not herself mention any personal or family names.[5][6][3][7] However, a brother's name was revealed by a journalist covering the Brooklyn Theatre fire of 1876.[4]

Vernon should not be confused with another actress of the same name, who was active in Cleveland theater during 1854-1855. This Cleveland actress was playing parts such as Ophelia and Desdemona more usual for a young woman than a girl of ten or eleven.[8][9]

Early career

[edit]Vernon said her parents agreed to place her with Thomas Barry and his wife, who became her first drama coaches. The Barrys took her to Boston as a member of the Boston Theatre stock company at $10 per week.[3] According to her later recollection, she made her first appearance on stage at age 12 in Boston on April 15, 1856, playing a blossom fairy in a production of A Midsummer Night's Dream.[5] Her first known verifiable credit was as Juno in The Tempest on September 15, 1856, with Thomas Barry as Prospero.[10] When Barry retired from the stage, Vernon continued with the Boston Theatre stock company, supporting John Gibbs Gilbert in The Corsair in February 1857.[11] In June 1857, she had her first stage triumph, when the new Boston Theatre manager took her to Montreal in She Stoops to Conquer.[12] Vernon recalled a half-century later being showered with flowers on the stage by her former schoolmates and friends.[3]

Back in Boston, Vernon supported Agnes Robertson in Jessie Brown; or, The Siege of Lucknow during April 1858.[13] She then joined Charlotte Cushman in Manhattan at Niblo's Garden in June 1858 for London Assurance.[14] Cushman was stern and abusive with rehearsal errors, a major change in style for Vernon who was used to the considerate and forgiving Barry.[3] Fortunately for Vernon, Cushman left Niblo's Garden in early July 1858,[15] and John Brougham took over.[16]

Louisville

[edit]Vernon, now fifteen, took on a visiting leading lady role at Louisville, Kentucky in September 1858.[17] She told interviewer Eileen O'Connor in 1916 that it was usual in those days for leading performers to visit stock companies around the country.[3] Vernon worked steadily with this company, with new productions each week, save for a period of illness at the end of 1858,[18] and a week's transfer to Cincinnati in March 1859.[19]

Vernon stayed at the Louisville Theater through May 1859, when it abruptly closed. Vernon wrote open letters to the leading Louisville newspapers that month, telling how the theater management siphoned off profits in Louisville, trying to prop up their failing Cincinnati theater operation. They had gradually reduced the performers wages over the season, and owed her and the other cast members back pay.[20][21]

Pre-war stage

[edit]Vernon returned to New York in June 1859, with an engagement at Laura Keene's Theatre.[22] She was a supporting player at this point, taking second place to the Sisters Gougenheim (Adelaide and Joey) who played the leading parts, both male and female.[23] By October 1859 she was back at Niblo's Garden performing with the stock company, starting with William Evans Burton in Dombey and Son.[24] Vernon joined with playwright-actor G. L. Aiken in his stage adaptation of The Hidden Hand by E. D. E. N. Southworth. They first performed it in Buffalo, New York during December 1859.[25] Taking advantage of The Octoroon, G. L. Aiken wrote The Fate of an Octoroon; or the Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, adapted from Harriett Beecher Stowe's work, with Vernon in the title role.[26]

In April 1860, Vernon took part in the inaugural performance at Mrs. Brougham's Theatre,[fn 2] which the New-York Tribune found underwhelming and suggested Mrs. Brougham's tenure "is not likely to be prolonged".[28] A week later Vernon had her first known trouser role as Prince Zamna in The Bronze Horse, for J. M. Nixon's Troupe at Niblo's Garden.[29] Nixon's Troupe was more circus than theater; the spectacle opened with Vernon mounting a real horse on stage and riding it some thirty feet up into canvas "clouds".[30]

The remodeled New Richmond Theatre opened on September 8, 1860, with Ida Vernon and Sallie Partington listed among eighteen others as the stock company.[31] For the first five months Vernon supported visiting stars, such as Emma Waller[32] and Joey Gougenheim.[33] In February 1861 she finally had her first "benefit",[fn 3] selecting a dramatization of The Woman in White, and Andy Blake by Dion Boucicault.[34]

American Civil War

[edit]Nashville and return to Richmond

[edit]With the outbreak of fighting in April 1861, Vernon's connection with the Richmond Theatre was temporarily severed. She appears next at the opening of the Nashville Theatre in September 1861, co-starring with Walter Keeble[fn 4] in The Gamester.[35] Vernon remained in Nashville through October, playing another trouser role as William in Black-Eyed Susan.[36] The announcement of her impending return to Virginia in The Richmond Times-Dispatch for the delayed opening of the theatre season,[37] was preceded by a short article on the difficulty British subjects were having in obtaining passports for crossing the battle lines to "Lincolndom".[38] Just prior to Vernon's departure from Nashville, her fellow actors and city residents gave her a benefit evening.[39]

Vernon did not return to the Richmond Theatre stage until December 2, 1861, when she starred in Camille, a stage adaptation of The Lady of the Camellias.[40] Just four days later she was given a benefit, for the "theatre has been literally crowded each night".[41] A local theatre critic mentioned that she was still new in her profession, but was willing to perform in the South when others were not. They concluded: "Miss Vernon is a Southern actress".[42]

During June 1862, Vernon was reunited with Walter Keeble at the Richmond Varieties,[fn 5] playing the leads in Romeo and Juliet. The venue had just reopened after a closure due to "the exigencies of the times".[45] Keeble and Vernon followed Romeo and Juliet with Richard III.[46] Vernon placed a reward notice in the Richmond Dispatch for bracelets stolen from her dressing room on July 8, 1862.[47] The Merchant of Venice was Vernon and Keeble's Shakespearean offering for August 1862. These programs usually contained a dance number by one or more of the Partington sisters and a one-act closer.[48]

Alabama sojourn and blockade running

[edit]Vernon went from Richmond to Montgomery, Alabama in November 1862.[49] It was December before she appeared in a production of The Iron Chest.[50] For New Year's Day 1863, Vernon played another trouser role as a page in Richelieu.[51] A Philadelphia paper reporting on Southern theatres said "Miss Ida Vernon is playing a successful star engagement" at Montgomery.[52] Vernon finished her Montgomery engagement on January 22, 1863, and was presented onstage with a set of jewelry from the citizens.[53]

From Montgomery, Vernon went to Mobile, Alabama, where she performed in Romeo and Juliet starting in late March 1863.[54] After four plays, a local newspaper said audiences had been "unusually large" for Miss Ida Vernon.[55] After a month-long engagement, Vernon was granted a complimentary benefit by popular acclaim, performing as Peg Woffington in Masks and Faces.[56]

Vernon appeared in Wilmington, North Carolina in late May 1864, having returned from the North. She had escorted a young niece, who had been living with her, across the lines back to the girl's parents.[57] Trying to return, she was caught and detained by Union authorities for a few days. She tried again, was caught once more and imprisoned at Fortress Monroe for six weeks. Eventually she travelled to Canada, where she caught a ship to Bermuda, and another to Wilmington.[58] The only contraband she brought back with her were copies of recent European plays that had not yet been seen in the South.[57] At Wilmington her leading man was Theodore Hamilton; they performed in The Stranger by August von Kotzebue,[59] and other stock works, concluding both their engagements with The Taming of the Shrew.[60]

Vernon returned to the New Richmond Theatre in August 1864, bearing with her the manuscript for a stage adaptation of East Lynne. It had never been performed in the Confederacy. Her leading man was the New Richmond Theatre's manager, Richard D'Orsay Ogden.[61] A Charleston correspondent wrote that Miss Ida Vernon was attracting large audiences to the theatre for East Lynne.[62] Though she performed in other works, East Lynne would be her mainstay for the next year. She took it to Wilmington, North Carolina in September and October 1864,[63][64] but suffered a severe illness on returning to Richmond in December 1864.[65]

The Siege of Richmond

[edit]During January 1865, a correspondent in Richmond wrote to The Charleston Mercury that Ida Vernon was holding a benefit performance of East Lynne to provide food for Confederate soldiers, with tickets costing 20 dollars.[66] Later that month, a Washington, D.C. newspaper reported that Ida Vernon was managing the Richmond Theater in that besieged city, since the male management were under arms.[67]

Starting on March 30, 1865, Vernon ran a daily ad in the Richmond Dispatch offering her costumes, private wardrobe, furniture, and possessions for sale, to raise money for going abroad for her health.[68] However, from later recounting, Vernon's possessions were either burned in the fires set by retreating Confederates, or confiscated by Union forces. After the Fall of Richmond, Vernon turned up in Montreal at the end of May 1865, starring in East Lynne.[69]

Post-war stage

[edit]

Surprisingly, Vernon was listed among a troupe of entertainers performing at Gold Hill, Nevada in July 1865.[70] This western mining town was wealthy enough to possess a music hall and the Gold Hill Daily News. The latter reported Vernon's arrival on July 1, 1865, via the Pioneer Stage Line,[71] which ran from Sacramento to nearby Virginia City, Nevada.[72] Vernon next reappears in Richmond, Virginia during October 1865, playing in East Lynne,[73] and the following month in Wilmington, North Carolina with the same work.[74]

Vernon returned to the New York stage in February 1866, after six years away. She starred in The Lady of Lyons at the Winter Garden Theatre, where Edwin Booth was performing in Richelieu.[75] Initially, Vernon performed only on Wednesday evenings, Booth's night off, as he performed in matinees on that day.[76] However, on March 14, 1866, they performed together for the first time in a Wednesday matinee of Ruy Blas.[77] Vernon supported Sidney Frances Bateman at Niblo's Garden in April 1866, taking over the leading lady spot after Bateman became ill in May 1866.[78]

Edwin Booth starred in Hamlet at the Winter Garden Theatre in November 1866, with Vernon, at age 23, playing Queen Gertrude.[79] She supported him in other Shakespearean tragedies through April 1867, with Methua Scheller playing the lead female roles. In May 1867, Vernon joined Boothroyd Fairclough in Hamlet at the French Theatre, playing Ophelia. Fairclough suffered from comparison to Booth in reviews, with Vernon's performance judged "conventional but endurable" by The New York Times,[80] and "good" by the New York Herald.[81]

An engagement at Pittsburgh's Opera House to perform in Nobody's Daughter in October 1867,[82] was cut short by a personal tragedy.[83] For almost two years there is little reference to Vernon on the stage, until a Manhattan revival of Uncle Tom's Cabin in September 1869, wherein she played Eliza.[84] She followed this with The Last Will in November 1869,[85] and supported George L. Fox at the Olympic Theatre during early 1870.[86][87]

The Two Orphans

[edit]

Vernon starred in Hand and Glove at Hooley's Opera House in Brooklyn during early October 1874.[88] She then joined the Union Square company, which played Washington's National Theatre later that month.[89] She was thus positioned to take a role in a new play from France, Les Deux orphelines by Adolphe d'Ennery and Eugène Cormon. Sheldon Shook, who owned the Union Square Theatre, and A.M. Palmer, who was the lessee-manager, commissioned Hart Jackson to provide an English-language adaptation, The Two Orphans. Jackson's version converted the original five-act melodrama into four acts and seven scenes. The American premiere came on December 21, 1874, with Kate Claxton and Kitty Blanchard in the title roles.[90] Vernon created the role of Sister Genevieve, matron of La Salpêtrière, who befriends the orphan Henriette in the prison-hospital, and which The New York Times reviewer said "is one of the most perfectly depicted characters of the drama".[91]

An instant success, by April 1875 seats for The Two Orphans were still selling a month in advance after over 100 performances had been given.[92] Finally the producers announced the theatre's season would close on June 15, 1875, after 180 performances, a run "which has no equal in the history of the American stage".[93]

Brooklyn Theatre fire

[edit]

After supporting Barry Sullivan in his 1875 engagement at Booth's Theatre,[94], Vernon rejoined the Union Square Theatre Company in December 1876 for a new presentation of The Two Orphans. This would be at the Brooklyn Theatre, with Kate Claxton and Vernon reprising their original roles.[95] On Tuesday evening, December 5, 1876, Vernon finished her part and left the theater with the final scene yet to play. She wasn't needed for the finish, so she returned to her rooms at No. 28 Johnson Street, two doors away from the Brooklyn Theatre. She was taking care of her brother, Capt. J. B. MacGowan, who suffered from "pulmonary affectation". He had been near death for several weeks; Vernon employed caretakers to watch him while she performed. Kate Claxton later testified that the Brooklyn Theatre fire broke out two minutes into the last scene of the play. Vernon heard the alarm and was able to get her brother out of the house before it too burned. She escaped with him to the nearby Pierrepont House, clad only in her dressing gown.[4] The conflagration killed over 275 people, including some actors and stage hands, with the majority of casualties coming from audience members in the upper galleries. Vernon was once again nearly destitute,[4] as after Richmond in April 1865, but was able to recover her jewels from the wreckage of her dressing room.[96]

Later stage work

[edit]Sister Genevieve marked the start of Vernon's professional transition to character roles. One such later part was as Lady Bracknell in the American and Broadway premiere for The Importance of Being Earnest. This production opened at the Empire Theatre on April 22, 1895, with an all-star cast that included William Faversham as Algernon, Henry Miller as Jack, Viola Allen as Gwendolen, and May Robson as Miss Prism. Americans weren't yet ready for this work; the critic for The New York Times pronounced it "laboriously witty" and said half the comedy fell flat with the audience.[97] The reviewer for The Sun was complimentary towards Vernon, saying she distinguished herself by saving a "tediously talkative character" from being tiresome.[98]

William Hodge

[edit]

Vernon was associated with star William Hodge for her last ten years on the stage. Beginning with The Man from Home in 1907, she performed on Broadway and on tour across the nation as a supporting member of Hodge's informal company. In The Man from Home she played Lady Creech, a dubious character assisting the play's villain. This work ran on Broadway through 1909, for 500 performances, after which it toured four years. Following that, she joined Hodge in his first production as playwright-performer, The Road to Happiness. Opening in 1913, this toured for two years before making a short Broadway run in 1915. Vernon's final performances were in Hodge's Fixing Sister starting with a three-month Broadway run in 1916. Vernon went on tour with this play until May 1917, when a series of falls[99] eventually convinced her it was time to retire.[100]

Personal life

[edit]

Vernon told a Chicago reporter in 1908 she had been engaged to Edwin Booth on two occasions, one of which was broken up by his daughter from an earlier marriage.[6] She married a man named A. A. Taylor during September 1867,[101] which gave her naturalized citizen status.[fn 6] A. A. Taylor was her manager in late September 1867,[fn 7] when they journeyed by train to Pittsburgh from New York. He suffered from mania a potu according to early accounts,[103] "a congestion of the brain" in later ones, and was taken to Mercy Hospital, where he jumped out of a third floor window, mortally injuring himself.[104]

A brief 1911 sketch of the stage actor Jean Clarendon, son of the late actor Hal Clarendon and playwright-performer Helen Mowat, identified Ida Vernon as his aunt.[105] An engagement announcement from 1922 said Vernon's niece, actress Anita Clarendon, was also the niece of Sir Oliver Mowat.[106]

New York legalized female suffrage in 1917;[107] Vernon registered to vote as a republican in October 1919, giving her age as 76 and her birthplace as "USA".[fn 8] She also claimed to be single, and the box for naturalized status by year of marriage was blank for her registration.[109]

Death

[edit]Ida Vernon was living "on a competency at the Marbury hall hotel", when she died of pneumonia on February 22, 1923, in New York City.[110] Her internment was to be in Sheldon, Vermont, though her connection with that town was tenuous. This was the hometown of her late niece's husband, Harry Smith; the couple had been buried there twenty years before. Vernon had spent some summers there in recent years.[110] Another niece, actress Anita Clarendon[fn 9] was vacationing with her husband William Trevor in Bermuda. They brought Vernon's body from Manhattan to Sheldon on March 3, 1923; it was buried that evening.[110]

Stage credits

[edit]| Year | Play | Role | Venue | Notes/Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1856 | A Midsummer Night's Dream | Fairy | Boston Theatre | Her first stage performance according to her later memory.[5] |

| The Tempest | Juno | Boston Theatre | Her first known credited role came 11 days after her thirteenth birthday.[10] | |

| 1857 | My Husband's Mirror | Margaret | Boston Theatre | Vernon was praised for her bit in this one-act comic opener by W. W. Clapp.[111] |

| The Corsair | Boston Theatre | [11] | ||

| She Stoops to Conquer | Miss Neville | Theatre Royal | [12] | |

| 1858 | Jessie Brown | Boston Theatre | Topical work on the Siege of Lucknow, written by Dion Boucicault.[13] | |

| London Assurance | Pert | Niblo's Garden | Vernon's first known Broadway credit.[14] | |

| The Rivals | Lydia Languish | Niblo's Garden | Vernon played the leading lady in this Sheridan classic.[112] | |

| Gold | Susan Merton | Louisville Theater | Vernon guest starred in this 1853 four-act drama by Charles Reade.[113] | |

| Honey Moon | Juliana | Louisville Theater | A benefit for Vernon, a comedy in eight acts in which she starred.[114] | |

| Adrienne the Actress | Angelique D'Aumont | Louisville Theater | Five-act play had Vernon take a supporting role for a new visiting star.[115] | |

| 1859 | Court and Stage | Catherine of Braganza | Laura Keene's Theatre | A comedy by Tom Taylor and Charles Reade.[22] |

| Dombey and Son | Niblo's Garden | This was John Brougham's 1848 adaptation of the Dickens' novel.[24] | ||

| The Hidden Hand | Capitola Black | Metropolitan Theatre | Adapted by G. L. Aiken, who also performed the male lead.[25] | |

| The Fate of an Octoroon | Lethe | Metropolitan Theatre | Five-act drama by Vernon's co-star, G. L. Aiken.[26] | |

| 1860 | The Rivals | Lucy | Mrs. Brougham's Theatre | Vernon was relegated to a featured role, with Mrs. Brougham playing Mrs. Malaprop.[27] |

| The Bronze Horse | Prince Zamna | Niblo's Garden | Vernon's first-known role as a male character had her on horseback.[29] | |

| Othello | Desdemona | New Richmond Theatre | At age 17, Vernon supported Emma Waller playing Iago with her husband in the title role.[32] | |

| Guy Mannering | Julia Mannering | Richmond Theatre | An adaption of Guy Mannering slanted to favor the gypsy Meg Merrilees, played by Emma Waller.[116] | |

| 1861 | An Unequal Match | Mrs. Montressor | Richmond Theatre | Vernon supported Miss Joey Gougenheim in this comedy by Tom Taylor.[117] |

| The Woman in White | Laura Fairlie | Richmond Theatre | An adaptation in which Vernon played the title character for her benefit.[34] | |

| The Gamester | Mrs. Beverly | Nashville Theatre | [35] | |

| Black-Eyed Susan | William | Nashville Theatre | Vernon plays a heroic Jack Tar at age 18.[36] | |

| Camille | Camille[fn 10] | Richmond Theatre | Vernon returned to Richmond with this adaptation from Alexandre Dumas fils.[40] | |

| 1862 | Romeo and Juliet | Juliet | Richmond Varieties | Walter Keeble from the Nashville Theatre was Vernon's Romeo.[45] |

| Richard III | Queen Elizabeth | Richmond Varieties | Walter Keeble played the title role.[46] | |

| The Merchant of Venice | Portia | Richmond Varieties | Walter Keeble played Antonio.[48] | |

| The Iron Chest | Montgomery Theatre | [50] | ||

| The Hunchback | Julia | Montgomery Theatre | E. R. Dalton played Master Waller in this production.[118] | |

| 1863 | Richelieu | François | Montgomery Theatre | [51] |

| Ye Gentle Savage | Pocahontas | Montgomery Theatre | [53] | |

| The Lady of Lyons | Pauline Deschapelles | Mobile Theatre | [119] | |

| Masks and Faces | Peg Woffington | Mobile Theatre | [56] | |

| 1864 | The Stranger | Mrs. Haller | Wilmington Theatre | The original German work was called Menschenhass und Reue (Misanthropy and Repentance).[59] |

| The Taming of the Shrew | Katherine | Wilmington Theatre | [60] | |

| East Lynne | Lady Isabel Vane | Richmond Theatre Theatre Royal |

Vernon played this five-act favorite in both Richmond and Montreal.[61][66][69] | |

| 1865 | Kathleen Mavourneen | Kathleen | Wilmington Theatre | An original work adapted from the popular song of the same name.[120] |

| 1866 | Ruy Blas | Princess | Winter Garden Theatre | Vernon's first performance with Edwin Booth.[77] |

| 1867 | Nobody's Daughter | Pittsburgh Opera House | "Sensation piece", adapted from a novel of the same name by Mary Elizabeth Braddon.[82] | |

| 1869 | Uncle Tom's Cabin | Eliza | Olympic Theatre | [84] |

| The Last Will | Olympic Theatre | A "domestic drama" in three acts, by Charles Dibdin Pitt.[85] | ||

| 1870 | The Writing on the Wall | Margaret Elton | Olympic Theatre | Four-act drama by Morton starred George L. Fox as a "model farmer".[86] |

| The Serious Family | Mrs. Ormsby Delmaine | Olympic Theatre | The New York Times said Vernon performed with "vivacity and effect.[87] | |

| 1874 | Hand and Glove | Lady Luxboro | Hooley's Opera House | [88] |

| Jane Eyre | Mrs. Sarah Reed | National Theatre | This was the adaptation by Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer starring Charlotte Thompson.[89] | |

| The Two Orphans | Sister Genevieve | Union Square Theatre | Hart Jackson's American adaptation of the French play had four acts and seven tableaux.[90] | |

| 1876 | The Two Orphans | Sister Genevieve | Brooklyn Theatre | Revival in December 1876 halted abruptly by the Brooklyn Theatre fire. |

| 1895 | The Importance of Being Earnest | Lady Bracknell | Empire Theatre | The Broadway and American premiere of Oscar Wilde's comedy lasted only two weeks.[97] |

| 1907 | The Man from Home | Lady Creech | Touring company Astor Theatre |

After the Broadway run finished in 1909, Vernon spent four years touring with this play. |

| 1913 | The Road to Happiness | Mrs. Whitman | Touring company Shubert Theatre |

Vernon had a featured part as the protagonist's crippled mother.[121] |

| 1916 | Fixing Sister | Lady Wafton | Touring company Maxine Elliott's Theatre |

The New York Times said William Hodge was the whole play.[122] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ They were sent as students for the convent school, not as novitiates. Vernon was later listed as Presbyterian in a postmortem document[1]

- ^ This was located at 444 Broadway, between Grand and Canal Streets.[27]

- ^ In 19th Century American theater, this was an evening where a stock player was rewarded for long service by choosing the plays to be performed, taking the roles they wanted, and collecting a portion of the box office for that night.

- ^ He was the sole lessee and manager of the theatre, as well as leading man.

- ^ The Richmond Theatre had burned down in January 1862.[43] This new venue was formerly known as Franklin Hall and was near the Exchange Hotel. It was being run by the former Richmond Theatre management.[44]

- ^ The concept of coverture was enshrined in 19th Century US law, giving women automatic naturalization upon marrying a US citizen.[2] For Vernon, this also covered any awkwardness about her Confederate associations, given that she was a British national during the war and had been twice imprisoned for blockade running.[102]

- ^ For unknown reasons, newspapers in 1867 described Taylor as Vernon's brother-in-law rather than her husband.[103][104]

- ^ This was in contrast to her answers for the New York State census in 1915,[108] and the US Census of 1920,[2] in which she claimed to have been born at sea.

- ^ This was Katherine Anita Clarendon, who lived with Ida Vernon from 1915,[108] through 1922.[106]

- ^ American adaptations usually called both the play and the central character "Camille", and dispensed with the change in color for the camellias Margaret Gautier wore.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c New York, U. S., Episcopal Diocese of New York Church Records, 1767-1970, for Isabella Ida Vernon Taylor, Manhattan > Joseph William Sutton Registers, 1916-1926, retrieved from Ancestry.com

- ^ a b c 1920 United States Federal Census for Ida V. Taylor, New York > New York > Manhattan Assembly District 10> District 0771, retrieved from Ancestry.com

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Connor, Eileen (February 1916). "Sixty Years on the Stage". Theatre Magazine. Chicago, Illinois: The Story-Press Corporation. pp. 77, 79.

- ^ a b c d "Miss Ida Vernon's Statement". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. December 6, 1876. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Mantle, Burns (April 15, 1908). "Fifty-two Years on the Stage". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Actresses Gone! Now Naughty, Beautiful Women Gain Applause". The Inter Ocean. Chicago, Illinois. April 15, 1908. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vernon, Ida (January 5, 1917). "What Famous Actresses Say". The Palladium Item. Richmond, Indiana. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Atheneum". The Cleveland Leader. Cleveland, Ohio. December 4, 1854. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Atheneum". The Cleveland Leader. Cleveland, Ohio. December 9, 1854. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Boston Theatre (ad)". Boston Evening Transcript. Boston, Massachusetts. September 15, 1856. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Boston Theatre". Boston Evening Transcript. Boston, Massachusetts. January 31, 1857. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theatre Royal". Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. June 15, 1857. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Boston Theatre". Boston Evening Transcript. Boston, Massachusetts. April 3, 1858. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Amusements: Niblo's Garden". The New York Herald. New York, New York. June 27, 1958. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Niblo's Garden (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. July 3, 1858. p. 6 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Niblo's Garden (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. July 7, 1858. p. 3 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Louisville Theater (ad)". Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. September 27, 1858. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theater". Louisville Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. January 10, 1859. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theater". Louisville Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. March 28, 1859. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Editors Louisville Courier". Louisville Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. May 7, 1859. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "To The Public". The Courier-Journal. Louisville, Kentucky. May 7, 1859. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Laura Keene's Theatre (ad)". The New York Herald. New York, New York. June 7, 1859. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Laura Keene's Theatre (ad)". The New York Herald. New York, New York. June 15, 1859. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "City Items: Theatrical". New-York Daily Tribune. New York, New York. October 3, 1859. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theater". Buffalo Commercial Advertiser. Buffalo, New York. December 19, 1859. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan Theatre". Buffalo Daily Republic. Buffalo, New York. December 23, 1859. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Mrs. Brougham's Theatre (ad)". The New York Herald. New York, New York. April 9, 1860. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mrs. Brougham's Theater". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. April 11, 1860. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Niblo's Garden (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. April 16, 1860. p. 7 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Operatic and Dramatic Matters". The New York Herald. New York, New York. April 16, 1860. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Richmond Theatre". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. September 6, 1860. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New Theatre (ad)". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. December 22, 1860. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Richmond Theatre (ad)". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. January 8, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Richmond Theatre (ad)". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. February 21, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Nashville Theatre". Republican Banner. Nashville, Tennessee. September 22, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Nashville Theatre". Republican Banner. Nashville, Tennessee. October 19, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Richmond Theatre". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. October 19, 1861. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Passports". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. October 19, 1861. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Miss Ida Vernon". The Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee. November 1, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Local Matters". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. December 2, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Theatre-- Benefit of Miss Ida Vernon". Richmond Enquirer. Richmond, Virginia. December 6, 1861. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Theatre-- Benefit of Miss Ida Vernon". Richmond Enquirer. Richmond, Virginia. December 13, 1861. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Local Matters". Richmond Dispatch. January 3, 1862. p. 2.

- ^ "Richmond Varieties". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. June 11, 1862. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Varieties". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. June 10, 1862. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Richmond Varieties". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. June 21, 1862. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lost, Strayed, etc". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. July 10, 1862. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Richmond Varieties". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. August 1, 1862. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Local Intelligence-- The Montgomery Theatre". Montgomery Daily Mail. Montgomery, Alabama. November 9, 1862. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New Advertisements". Montgomery Daily Mail. Montgomery, Alabama. December 5, 1862. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New Advertisements-- Theatre". Montgomery Daily Mail. Montgomery, Alabama. January 1, 1863. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatres at the South". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. January 13, 1863. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New Advertisements-- Theatre". Montgomery Daily Mail. Montgomery, Alabama. January 23, 1863. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre". Register and Advertiser. Mobile, Alabama. March 23, 1863. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Local Intelligence". Register and Advertiser. Mobile, Alabama. March 29, 1863. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theatre". Advertiser and Register. Mobile, Alabama. April 21, 1863. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theatre- The Stars". The Daily Journal. Wilmington, North Carolina. June 1, 1864. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ida Vernon, Actress, Dead". Springfield Evening Union. Springfield, Massachusetts. March 3, 1923. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theatre". The Daily Journal. Wilmington, North Carolina. June 1, 1864. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theatre". The Daily Journal. Wilmington, North Carolina. June 8, 1864. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New Richmond Theatre". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. August 15, 1864. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hermes (August 31, 1864). "Letter From Richmond". The Charleston Mercury. Charleston, South Carolina. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre (ad)". The Daily Journal. Wilmington, North Carolina. September 21, 1864. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre (ad)". The Daily Journal. Wilmington, North Carolina. October 15, 1864. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Amusements: Richmond Theatre". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. December 28, 1864. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Hermes (January 4, 1865). "Letters From Richmond". The Charleston Mercury. Charleston, South Carolina. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Southern managers... (no title)". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. January 31, 1865. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "For Sale, Privately". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. March 30, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Theatre Royal". Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. May 31, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Inform Yourselves!". Gold Hill Daily News. Gold Hills, Nevada. July 12, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Arrivals and Departures". Gold Hill Daily News. Gold Hills, Nevada. July 1, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Change of Time! Pioneer Stage Line". Gold Hill Daily News. Gold Hills, Nevada. July 1, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Richmond Theatre". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. October 17, 1865. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre (ad)". The Wilmington Herald. Wilmington, North Carolina. November 16, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Winter Garden". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. February 17, 1866. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Winter Garden". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. March 5, 1866. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Winter Garden". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. March 13, 1866. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Theaters To-Day". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. May 12, 1866. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Amusements". The New York Times. New York, New York. November 27, 1866. p. 7 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Amusements: The French Theatre". The New York Times. New York, New York. May 21, 1867. p. 5 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "French Theatre". The New York Herald. New York, New York. May 21, 1867. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Amusements". The Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. October 1, 1867. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Public Amusements". The Daily Commercial. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. October 2, 1867. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Olympic Theatre". The New York Herald. New York, New York. September 5, 1869. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Musical and Theatrical Notes". The New York Herald. New York, New York. November 17, 1869. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Olympic Theatre (ad)". The New York Herald. New York, New York. January 3, 1870. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Amusements". The New York Times. New York, New York. February 1, 1870. p. 5 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b "Hooley's Opera House". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. October 1, 1874. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Jane Eyre at the National". The Washington Chronicle. Washington, D.C. October 28, 1874. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Union Square Theatre (ad)". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. December 21, 1874. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dramatic: Union Square Theatre". The New York Times. New York, New York. December 27, 1874. p. 7 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Amusements: Union Square Theatre (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. April 5, 1875. p. 7 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Union Square Theatre (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. June 13, 1875. p. 11 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Amusements: Booth's Theatre (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. August 22, 1875. p. 11 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Amusements: Brooklyn Theatre (ad)". The Brooklyn Union. Brooklyn, New York. December 1, 1876. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Brief Chronicle". The Daily Messenger. St. Albans, Vermont. December 14, 1876. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New Theatrical Bills". The New York Times. New York, New York. April 23, 1895. p. 5 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Oscar Wilde's New Play". The Sun. New York, New York. April 23, 1895. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Actress Falls And Is Painfully Hurt". The Kalamazoo Gazette. Kalamazoo, Michigan. May 1, 1917. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bregg, Charles M. (October 14, 1917). "News and Notes of the Theater". Pittsburgh Post Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. p. 46 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Were Stage Favorites In Days Long Gone By". The Brooklyn Times. Brooklyn, New York. April 25, 1903. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Noted Actress is Buried In Sheldon". Burlington Daily News. Burlington, Vermont. March 7, 1923. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "A Fatal Leap - Shocking Death". Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. October 2, 1867. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "A Sad Affair". The Evening Telegraph. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 4, 1867. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "An Actor At Age Of Three Months". The Times. Streator, Illinois. September 25, 1911. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Anita Clarendon, Actress, Engaged". The New York Herald. New York, New York. June 24, 1922. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Recognizing Women's Right to Vote in New York State | New York Heritage". nyheritage.org. Retrieved 2023-10-03.

- ^ a b Ida Vernon in the New York, U. S., State Census, 1915, New York > New York > A.D.27E.D.15, retrieved from Ancestry.com

- ^ Ida V. Taylor in the Manhattan, New York, New York, U.S., Voter Registers, 1915-1956, retrieved from Ancestry.com

- ^ a b c "Noted Actress Is Buried At Sheldon". St. Albans Daily Messenger. St. Albans, Vermont. March 9, 1923. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Boston Theatre". Boston Evening Transcript. Boston, Massachusetts. January 6, 1857. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Niblo's Garden (ad)". The New York Times. New York, New York. July 12, 1858. p. 6 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Theater- "Gold"". Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. September 30, 1858. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Louisville Theater (ad)". Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. October 1, 1858. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Louisville Theater (ad)". Daily Courier. Louisville, Kentucky. October 4, 1858. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Richmond Theatre (ad)". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. December 27, 1860. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Richmond Theatre (ad)". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. January 12, 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Advertisements-- Theatre". Montgomery Daily Mail. Montgomery, Alabama. December 17, 1862. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre". Register and Advertiser. Mobile, Alabama. March 26, 1863. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre". Wilmington Herald. Wilmington, North Carolina. November 30, 1865. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "William Hodge In A Bucolic Comedy". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. August 31, 1915. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "William Hodge In 'Fixing Sister'". The New York Times. New York, New York. October 5, 1916. p. 9 – via NYTimes.com.