Hoplophoneus

| Hoplophoneus | |

|---|---|

| |

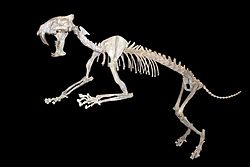

| H. primaevus skeleton, Zurich natural history museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | †Nimravidae |

| Subfamily: | †Hoplophoninae |

| Genus: | †Hoplophoneus Cope, 1874 |

| Type species | |

| Hoplophoneus primaevus Leidy, 1851

| |

| Other Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

H. occidentalis

H. primaevus

| |

Hoplophoneus (Greek: "murder" (phonos), "weapon" (hoplo)[1]) is an extinct genus of the family Nimravidae, lived in North America and Asia during the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene epochs from 35.7 to 30.5 mya, existing for approximately 5.2 million years.[2][3]

Taxonomy

[edit]

H. strigidens was considered nomen dubium by Bryant in 1996.[4] In 2000, an unnamed species of Hoplophoneus within Late Eocene rocks was found in Thailand.[5]

In 2016, all North American species of Eusmilus were placed in Hoplophoneus by Paul Z. Barrett.[6] However, in 2021, Barret revised this phylogeny. His phylogenetic analysis suggests H. cerebralis, H. dakotensis, and H. sicarius were actually species of Eusmilus instead of Hoplophoneus.[3]

Description

[edit]Hoplophoneus, though not a true cat, was similar to cats in outward appearance, though with a robust body and shorter legs. While a 2008 study estimated that the largest individual have weighed 160 kg (350 lb), similar to a large jaguar.[7] Other experts suggested a smaller size. Turner suggested H. occidentalis was about the size of a large leopard and had canine teeth of only moderately-larger size.[8] Based on a sample size of 8 specimens, Meachen found that the species weighed 65 kg (140 lb).[9] H. primaevus was significantly smaller than H. occidentalis, estimated to have weighed 15–19.5 kg (33–43 lb).[10][9]

Paleobiology

[edit]Brain anatomy

[edit]The posterior vermis of the cerebellum was found to be straight, although the overlap of the cerebellum by the cerebrum was smaller than extant felids. It was also found that the olfactory bulbs were relatively small in Hoplophoneus.[11] Despite this, H. primaevus was found to similar encephalization quotient to cougars, and scoring higher than jaguars.[12]

Predatory behavior

[edit]H. occidentalis shows specialization for large prey with robust bones and larger areas for muscle attachments.[9] Lautenschlager et al. 2020 estimated the jaw gape for this species to be around 98.22 degrees. They argue due to the wide jaw gape of over 90 degrees, combined with little bending strength values over time suggests they have an intermediate killing strategy towards large prey.[13] Including supplementary materials

Pathology

[edit]An adult specimen of H. primaevus discovered in Badlands National Park, South Dakota, in 2010 by paleontologist Clint Boyd et al. was found to have bite marks on its skull from the teeth of another adult individual of Hoplophoneus. From examination of the wounds, it was found that the animal had been wounded by its rival's saber-teeth. Regrowth of bone around the injuries shows that the nimravid survived the attack. Similar finds also reveal that such fights were likely commonplace among nimravids and that they would often aim for the back of the skulls and eyes of their opponents.[14]

Paleoecology

[edit]H. occidentalis was found in the Brule Formation of South Dakota. It coexisted with predators such as the contemporary species H. primaevus, entelodontidae Archaeotherium mortoni, hyaenodontinae Hyaenodon and contemporary herbivores such the extinct camel Poebrotherium wilsoni, and extinct rhino Subhyracodon.[15]

H. primaevus was the dominant cat-like predator, with its only serious competitor being the larger hyaenodonts like Hyaenodon.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ "Glossary. American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on 20 November 2021.

- ^ Turner, Alan. National Geographic Prehistoric Mammals. National Geographic, 2004., pp.120-121

- ^ a b Barrett, Paul Zachary (26 October 2021). "The largest hoplophonine and a complex new hypothesis of nimravid evolution". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 21078. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1121078B. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00521-1. PMC 8548586. PMID 34702935. S2CID 240000358.

- ^ Prothero, DR; Emry, RJ; Bryant, HN (1996). "Nimravidae". The Terrestrial Eocene-Oligocene Transition in North America. pp. 453–475.

- ^ Peigné, Stéphane; Chaimanee, Yaowalak; Jacques, J. J; Suteethorn, Varavudh; Ducrocq, Stéphane (March 2000). "New Eocene nimravid carnivoran from Thailand". Journal of Verterbrate Paleontology. 20 (1): 157–163.

- ^ Barrett PZ. (2016) Taxonomic and systematic revisions to the North American Nimravidae (Mammalia, Carnivora) PeerJ 4:e1658 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1658

- ^ Sorkin, B. (2008-04-10). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators". Lethaia. 41 (4): 333–347. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x.

- ^ Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives: an illustrated guide. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 234. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5.

- ^ a b c Meachen, J. A. (2012). "Morphological convergence of the prey-killing arsenal of sabertooth predators". Paleobiology. 38 (1). doi:10.2307/41432156.

- ^ Dubied, Morgane; Solé, Floréal; Mennecart, Bastien (29 July 2019). "The cranium of Proviverra typica (Mammalia, Hyaenodonta) and its impact on hyaenodont phylogeny and endocranial evolution". Paleontology. 62 (6): 983–1001. doi:10.1111/pala.12437.

- ^ Lyras, George A.; Geer der van, Alexandra Anna; Werdelin, Lars (November 2022). "Paleoneurology of Carnivora". Paleoneurology of Amniotes, New Directions in the Study of Fossil Endocasts. pp. 681–710. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13983-3_17.

- ^ Dubied, Morgane; Solé, Floréal; Mennecart, Bastien (29 July 2019). "The cranium of Proviverra typica (Mammalia, Hyaenodonta) and its impact on hyaenodont phylogeny and endocranial evolution". Paleontology. 62 (6): 983–1001. doi:10.1111/pala.12437.

- ^ Lautenschlager, Stephan; Figueirido, Borja; Cashmore, Daniel D.; Bendel, Eva-Maria; Stubbs, Thomas L. (2020). "Morphological convergence obscures functional diversity in sabre-toothed carnivores". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287 (1935): 1–10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.1818. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 7542828. PMID 32993469.

- ^ The Dakota Badlands Used to Host Sabertoothed Pseudo-Cat Battles

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Brule Formation

- ^ Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780253010421.