History of Besançon

Classified as a City of Art and History and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Besançon possesses a significant architectural heritage. Originating as a Gallic oppidum, the city evolved into an important cultural, military, and economic center.[1] Alternating between Germanic and French control, the capital of Franche-Comté has preserved numerous historical elements dating from Antiquity to the 19th century.[2][3]

Mottos and heraldry

[edit]

The city of Besançon has used several mottos throughout its history. Utinam ("May it please God") is considered the official motto[4] and appears on various public monuments, including the fountain at Place Jean Cornet, the pediments of the Rivotte school and the Palace of Justice, and the war memorial. In 1815, it was briefly replaced by Deo et caesari fidelis perpetuo ("Eternal loyalty to God and Caesar"), before the original motto was reinstated.[5]

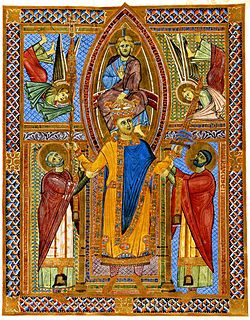

The city's coat of arms includes an eagle granted by Emperor Charles V in 1537, accompanied by two triumphal columns symbolizing the ancient Gallo-Roman city of Vesontio.[6] The eagle was originally double-headed, reflecting the heraldry of the Holy Roman Empire.[7]

Prehistory

[edit]An ideal settlement site from the origins

[edit]Archaeological evidence confirms the presence of hunter-gatherer groups in the area around Besançon during the Middle Paleolithic period, approximately 50,000 years ago. Excavations have also revealed Neolithic settlements along the Doubs River, particularly at the base of the Roche d'Or and Rosemont hills,[8] with traces of habitation dating to around 4000 BCE.[9]

Antiquity

[edit]

The Gallic oppidum of Vesontio

[edit]In the 2nd century BCE, the oppidum was occupied by the Sequani, a Celtic people whose territory extended between the Rhône, Saône, Jura, and Vosges.[10] Archaeological excavations have confirmed the existence of public infrastructure from this period, with the oldest remains uncovered during rescue excavations in 2001 near the site of the former ramparts.[11] The settlement was enclosed by a shore wall (murus gallicus), traces of which were found at the same location. A craftsman district was situated outside the oppidum.[12]

Known in Latin as Vesontio, the site served as the economic center of the Sequani territory. It was later contested by Germanic tribes and the Aedui before being conquered by Julius Caesar in 58 BCE.[13]

Vesontio, Gallo-Roman city

[edit]Julius Caesar, noting the strategic location of the site in Commentaries on the Gallic War,[14] designated it as the capital of the Sequani tribe (Civitas Maxima Sequanorum), as well as a military citadel and commercial center in Roman Gaul.[15] The city subsequently experienced significant development, becoming one of the largest urban centers in Belgic Gaul and later in the province of Upper Germany.[16]

In 68 CE, Vesontio was the site of a confrontation between Lucius Verginius Rufus, loyal to Emperor Nero, and the rebel Gaius Julius Vindex, who was defeated and later took his own life.[17] Following the suppression of the Batavian revolt led by Civilis, the city was likely granted the status of Roman colony, although the exact date remains uncertain.[18] During this period, the Romans undertook significant urban development, constructing numerous buildings along the cardo (present-day Grande Rue) and on the right bank of the Doubs River, including an amphitheater (the Besançon Arena) with a capacity of up to 20,000 spectators.[19] Archaeological investigations have identified over 200 Roman-era sites in the La Boucle area and adjacent neighborhoods.

Under the Tetrarchy, Vesontio became the capital of the Provincia Maxima Sequanorum. Notable Roman-era remains include the Porte Noire (Black Gate), erected under the reign of Marcus Aurelius around 175 CE, possibly commemorating the end of the conflicts of 172–175 CE;[20] the colonnades of Square Castan; the conduits of the Roman aqueduct that supplied the city with water; the remains of the amphitheater; and two Roman domus located beneath the current Palace of Justice and the Lumière College. The latter site yielded the Medusa Mosaic, which has been restored and is now housed in the Museum of Fine Arts and Archaeology of Besançon.[21] In 360 CE, Emperor Julian referred to Vesontio as a "village clustered on itself," reflecting its decline during that period.[22]

Middle Ages

[edit]

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Clovis, King of the Franks, incorporated the territory of the Sequani, along with that of the Burgundians and Alemanni, into his kingdom.[23] The early medieval history of Besançon is not well documented due to the limited availability of sources. The city is first mentioned in writing in 821 under the name Chrysopolis.[24] Between 843 and 869, the Diocese of Besançon was part of Middle Francia, then of Lotharingia. After the death of Lothair II, the region was assigned to Charles the Bald under the Treaty of Meerssen in 870 and became part of the Kingdom of West Francia until 879.[25]

Besançon, ecclesiastical metropolis

[edit]

In 888, Odo I of France founded the Duchy of Burgundy and the County of Outre-Saône as part of the feudal reorganization of the kingdom. The County of Outre-Saône, with Dole as its capital, was associated with the County of Varais, which included Besançon.[26] In the same year, Rudolph I of Burgundy was elected King of Upper Burgundy, challenging the authority of the West Frankish kingdom over the territory that would become Franche-Comté.[27]

The County of Burgundy was formally established in 982, with Otto-William as its first count (bearing the title of Palatine Count of Burgundy).[28]

In 1032, following the death of King Rudolph III of Burgundy without a male heir, the region was bequeathed to his nephew, Emperor Henry II of the Holy Roman Empire. Besançon, like the rest of the County of Burgundy, was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire.[29] During this period, Archbishop Hugues de Salins, with the support of the Emperor, assumed lordship over Besançon. The city, elevated to the status of an archbishopric, gained independence from the County of Burgundy. After Hugues de Salins died in 1066, a succession crisis triggered a prolonged period of instability. Throughout the Middle Ages, Besançon remained directly under imperial authority and independent from the County of Burgundy, whose capital was Dole. The city played a role in imperial affairs, particularly hosting the Diet of Besançon in 1157.[30]

Besançon, free imperial city

[edit]During the 12th and 13th centuries, the inhabitants of Besançon opposed the authority of the archbishops and gradually secured communal liberties. These were formally granted in 1290 following two sieges that ended in an agreement. While remaining under the sovereignty of the Holy Roman Emperor, the city gained self-governance, administered by a council of twenty-eight elected notables and a council of fourteen governors appointed by them.[31]

Besançon thus held the status of a free imperial city for nearly four centuries. During this period, the Dukes of Burgundy, who also held the title of Count of Burgundy, served as protectors of the city. This era was marked by economic and political stability.[32]

Modern era

[edit]

During the Renaissance, Franche-Comté strengthened its ties with the Holy Roman Empire following the death of Charles the Bold.[33] Under Emperor Charles V, Besançon was fortified and became a strategic stronghold of the Empire. Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle, a native of Franche-Comté, served as Chancellor of the Empire from 1519 and Keeper of the Seals from 1532. The city benefited from imperial patronage, resulting in the construction of buildings such as the Granvelle Palace and the Town Hall, the latter featuring a statue of Charles V on its façade. In 1518, Besançon had an estimated population of 8,000 to 9,000, which may have increased to between 11,000 and 12,000 by 1608.[34] The local economy remained predominantly rural, with viticulture serving as the primary activity, particularly in the Battant district, where winegrowers constituted a significant portion of the population.[35] In 1575, the city was the site of a battle between Protestant and Catholic forces, which ended in a Catholic victory.

The "suffering century" and the French conquest

[edit]In contrast to the prosperity of the 16th century, Besançon faced significant challenges in the 17th century due to wars and economic hardship.[36] The period also faced criminal activity, exemplified by the execution of Barthélemy Labourey on May 12, 1618, whose name became associated with Revolution Square as part of local lore.[37]

In 1631, Besançon hosted the Duke of Orléans, brother of the French king and opponent of Cardinal Richelieu, twice.[38] During the Ten Years’ War (1635–1644), a regional phase of the Thirty Years’ War, the area endured plague, famine, and hardship. Although Besançon avoided direct sieges, it was affected by a plague outbreak in 1636 and famine from 1638 to 1644, mirroring the suffering of the surrounding region.[39]

A proposed territorial exchange between the city of Frankenthal, under Spanish control, and Besançon, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, was introduced in 1651 and accepted by the citizens of Besançon in 1664.[40] As a result, Besançon temporarily lost its status as a free imperial city and became a possession of the Spanish Crown from 1664 to 1674. Despite this change, Spanish influence remained limited due to geographic distance, and the city continued to regard itself, with some difficulty, as a free city. Tensions with France resumed shortly thereafter. On 8 February 1668, French forces led by the Prince of Condé entered the city after a brief siege and the capitulation of local authorities. The occupation was not well-received by the population, and French troops withdrew on 9 June 1668.[41] In response to the inadequacy of the city's defenses, construction efforts were undertaken to strengthen its fortifications. The foundation stone of a citadel on Mont Saint-Étienne was laid on 29 September 1668, and additional fortification works were initiated on the heights of Battant, particularly around Charmont.[42]

On 26 April 1674, the Duke of Enghien led a French army of approximately 15,000 to 20,000 troops[43] in a siege of Besançon. After 27 days, the city's citadel capitulated on 22 May 1674. The siege was notable for the presence of King Louis XIV, military engineer Vauban, and Minister Louvois.[44] Besançon was designated the capital of Franche-Comté by letters patent on 1 October 1677, replacing Dole. Various administrative institutions—including the military command, the intendancy, the parliament, and the university—were progressively transferred to the new capital.[45] The Treaties of Nijmegen, signed between 17 September 1678 and 5 February 1679, formalized the annexation of Besançon and the surrounding region into the Kingdom of France.[46]

Louis XIV designated Besançon as a key part of France's eastern defense system and assigned Vauban to oversee its fortification.[47] Between 1674 and 1688, the citadel was completely redesigned, with additional fortifications constructed from 1689 to 1695. Numerous barracks were also built beginning in 1680.[48] The construction of the citadel was costly.[48]

Era of prosperity

[edit]In the 18th century, under the administration of effective intendants, Franche-Comté experienced a period of prosperity. During this time, Besançon's population grew from approximately 14,000 to 32,000 inhabitants, and the city was developed with new monuments and private mansions.[49]

Contemporary era

[edit]After the Revolution

[edit]In 1790, Besançon lost its status as an archbishopric and its role as a regional capital, becoming the chief town of a department that excluded the most productive agricultural areas of the low country.[50] The population declined from an estimated 32,000 before the French Revolution to 25,328 in 1793, rising slowly to 28,463 by 1800.[51] During this period, the watchmaking industry was established in the city following the founding of a watch factory in 1793 by Swiss refugees led by Geneva watchmaker Laurent Mégevand.[52] Despite initial difficulties and local resistance, the industry grew, with approximately 1,000 watchmakers by 1795 and production increasing from 14,700 pieces in 1794–1795 to 21,400 in 1802–1803. In 1801, Besançon regained its status as an archbishopric with revised boundaries. The city was besieged during the French Campaign of 1814.[53]

From one war to the next (1870–1945)

[edit]In 1871, a plan to establish a Besançon Commune was proposed in connection with the Jura Federation, but was not realized. During the Third Republic, the city's population remained around 55,000 for several decades. The watchmaking industry continued to grow, producing 395,000 watches in 1872 and 501,602 in 1883. By 1880, Besançon accounted for 90% of French watch production, employing approximately 5,000 specialized workers and 10,000 part-time female workers.[54] Although the industry faced competition from Switzerland and experienced a crisis in the late 19th century, it recovered by 1900, with production reaching 635,980 watches, employing around 3,000 workers by 1910.[55] Other industries during this period included brewing, paper manufacturing, and metallurgy. The textile industry also developed after Count Hilaire de Chardonnet introduced an industrial process for producing artificial silk, leading to the establishment of a silk factory at Prés-de-Vaux in 1891.[56]

At the end of the 19th century, Besançon developed a thermal tourism industry with the creation of the Compagnie des Bains salins de la Mouillère in 1890.[57] This led to the construction of a thermal establishment, the Hôtel des Bains, a casino, the Kursaal performance hall, and the opening of a tourist office in 1896.[58] In 1910, the city experienced a flood.[59]

During World War II, German forces occupied Besançon on June 16, 1940, despite French efforts to destroy the city's bridges to hinder their advance.[60] Located in the occupied zone, near the demarcation line and within the prohibited zone, Besançon faced potential annexation to the Reich if Germany had won the war.[61] The city experienced limited destruction, with damage from a British air raid on July 15–16, 1943, targeting the Viotte district, resulting in 50 deaths, 40 serious injuries, and approximately 100 minor injuries.[62] Resistance activities began in 1942,[63] prompting German reprisals, including the execution of 16 resistance fighters at the Citadel of Besançon on September 26, 1943,[64] followed by 83 more executions. Allied forces, including the U.S. Army's 6th Corps, liberated Besançon on September 8, 1944, after four days of combat.[65] General de Gaulle visited the city on September 23, 1944,[66] followed by a joint visit with Winston Churchill on November 13, 1944.

Among the most famous members of the Resistance were Gabriel Plançon, Jean and Pierre Chaffanjon, Henri Fertet, the Mercier brothers, Raymond Tourrain, Marcelle Baverez, Henri Mathey, and Robert Bourgeois.[67]

Unprecedented expansion (1945–1973)

[edit]Following World War II, Besançon experienced significant growth, mirroring national trends. The city's population doubled from 63,508 in 1946 to 113,220 by 1968, with a growth rate of 38.5% between 1954 and 1962, surpassed by Grenoble and Caen.[68] Infrastructure development lagged behind this expansion:[69] the railway line to Paris was electrified in 1970, canal upgrades for larger traffic were proposed in 1975, and the highway reached Besançon in 1978. Plans for an airport in La Vèze were considered but abandoned.

After World War II, Besançon's watchmaking industry, while still prominent, declined from 50% of industrial jobs in 1954 to 35% by 1962, as textiles, construction, and the food industry grew.[70] In 1962, three companies employed over 1,000 workers: watchmaking firms Lip and Kelton-Timex, and the textile manufacturer Rhodia.[71] Besançon maintained its status as France's watchmaking capital, supported by its administrative and research roles.[72] The textile sector also thrived, with Rhodia employing 3,300 workers by 1966 and Weil, a leading men’s clothing manufacturer, reaching 1,500 employees in 1965.[73]

To address the housing crisis driven by rapid population growth, Besançon’s municipality initiated construction of the Montrapon and Palente-Orchamps housing estates in 1952, followed by the les 408 buildings in 1960, which housed primarily working-class residents.[74] Urban development proceeded unevenly, prompting a modernization plan between 1961 and 1963. This plan established the Planoise priority urban development zone (Z.U.P.), the Palente and Trépillot industrial zones, and the La Bouloie university campus,[75] alongside three boulevards to improve traffic flow.

Besançon was designated a regional capital following the establishment of regional action districts by a decree on June 2, 1960.[76]

In 1969, a proposed central business district, designed by Maurice Rotival, involved demolishing the train station but was abandoned in the mid-1970s.[77][78]

Crises and transformations (1973 to the present)

[edit]

The 1973 oil crisis triggered a severe economic downturn in Besançon, halting its industrial growth. The crisis was epitomized by the Lip affair,[79] where the watchmaking company faced layoffs in 1973, leading to a self-management-based labor movement and a significant protest, the Lip march, on September 29, 1973, drawing 100,000 people. Despite a temporary resumption of operations, Lip went bankrupt in 1977. In 1982, the closure of the Rhodia textile factory resulted in nearly 2,000 job losses,[80] followed by the shutdown of the Kelton-Timex watchmaking company. During the 1990s, the Weil garment company relocated, reducing its workforce from over 1,000 to under 100.[81] Over two decades, Besançon lost approximately 10,000 industrial jobs, facing significant challenges in recovery.

Following the 1982 decentralization laws, Besançon transitioned from an industrial hub to a tertiary center. Its two-century watchmaking tradition was redirected toward microtechnology, precision mechanics, nanotechnology, and time-frequency technology, gaining recognition at European and global levels. The city's quality of life, cultural heritage, and strategic location on the Rhine-Rhône corridor, a major European route, supported its economic revival in the early 21st century.[82]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Besançon, ville d'art et d'histoire" [Besançon, city of art and history]. Grand Besancon Métropole (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ "Besançon lève le voile sur son "Beau Siècle" à travers une exposition fascinante" [Besançon unveils its “Beau Siècle” through a fascinating exhibition]. GEO (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fromage, Arnaud. "La Franche-Comté... Toute une histoire" [Franche-Comté... A rich history]. FranceBleu (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ "Recueil d'armoiries de villes de France peintes au XVIe siècle - chapitre #05 (final) - Parlements du sud du royaume de France" [Collection of coats of arms of French cities painted in the 16th century - chapter #05 (final) - Parliaments of the southern kingdom of France]. Herald Dick Magazine (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ De boudemange, Inès (July 27, 2022). "Rennes, Arles, Beaune... Découvrez les devises de ces villes françaises" [Rennes, Arles, Beaune... Discover the mottos of these French cities]. Langue Francaise (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ "La Renaissance ay musée du Temps" [The Renaissance at the Musée du Temps] (PDF). Palais Granvelle (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Gantet, C (2009). "Le Saint-Empire" [The Holy Roman Empire]. L'Europe en conflits [Europe in conflict] (in French). Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 61–78. doi:10.4000/books.pur.119253. ISBN 978-2-7535-0656-5. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen, Claude (1992). Histoire de Besançon [History of Besançon] (in French). Vol. 1. Editions Cêtre. pp. 29–34. ISBN 978-2901040217.

- ^ Pétrequin, P; Pétrequin, A.-M (2021). "Le Néolithique avant la chronologie absolue, de 1835 à 1970" [The Neolithic period before absolute chronology, from 1835 to 1970]. La Préhistoire du Jura et l'Europe néolithique en 100 mots-clés [The Prehistory of the Jura and Neolithic Europe in 100 keywords] (in French). Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté. pp. 30–42. doi:10.4000/books.pufc.41935. ISBN 978-2-84867-846-7.

- ^ "De Vesontio à Besançon, la ville s'expose" [From Vesontio to Besançon, the city on display] (in French). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Daubigney, Alain (2009). "Brun P., Ruby P., L'Âge du Fer en France : premières villes, premiers États celtiques" [Brun P., Ruby P., The Iron Age in France: the first cities, the first Celtic states]. Revue archéologique de l'Est (in French). 58: 516–519. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Buchsenschutz, O. "Les Celtes et la formation de l'Empire romain" [The Celts and the formation of the Roman Empire.]. Annales: Histoire, Sciences Sociales (in French) (2): 337–361. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Rowe, Sam. "" Nos ancêtres les Gaulois ": national histories and the misuse of history". Doing History in Public. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Hirtius, Aulus; Caesar, Julius. Commentarii de Bello Gallico [Commentaries on the Gallic War] (in French). Vol. 1, section 34.

- ^ César, Jules (2006). La guerre des Gaules [The Gallic Wars] (in French). GALLIMARD. ISBN 978-2070336654.

- ^ Gaston, Christophe; Munier, Claudine (2018). "Un quartier de la ville antique de Vesontio (Besançon)" [A neighborhood in the ancient city of Vesontio (Besançon)]. Archéopages (in French). 46: 36–43. doi:10.4000/archeopages.3950. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Leclant, Jean (2011). Dictionnaire de l'Antiquité [Dictionary of Antiquity]. Quadrige (in French) (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-2-13-058985-3.

- ^ Gonzales, A; Walter, H (2006). "Permanences et mutations d'une cité gauloise devenue capitale de civitas romaine" [Continuity and change in a Gallic town that became the capital of a Roman civitas]. De Vesontio à Besançon [From Vesontio to Besançon] (in French). Besançon. p. 75.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "BESANCON GALLO-ROMAIN" [Gallo-Roman Besançon] (in French). Archived from the original on April 4, 2002.

- ^ Christol, Michel (2010). "L'organisation des communautés en Gaule méridionale (Transalpine, puis Narbonnaise) sous la domination de Rome" [The organization of communities in southern Gaul (Transalpine, then Narbonese) under Roman rule]. Pallas (in French). 84 (84): 15–36. doi:10.4000/pallas.3341. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ "Découverte exceptionnelle de mosaïques gallo-romaines sous un collège à Besançon (Doubs)" [Exceptional discovery of Gallo-Roman mosaics under a school in Besançon (Doubs)] (PDF). Le Doubs (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Case, John (January 18, 2024). "Julian the Apostate's Attempt to Restore Roman Paganism". Hillsdale College. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Goffart, Walter (1980). Barbarians and Romans, A.D. 418-584: The Techniques of Accommodation. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv131bttm. ISBN 978-0-691-21631-7. JSTOR j.ctv131bttm. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ François, Lassus (1982). "Toponymie et microtoponymie" [Toponymy and microtoponymy]. Le médiéviste et l'ordinateur (in French). 8 (8): 4–8. doi:10.3406/medio.1982.1002. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1992, pp. 214–219

- ^ "La Franche-Comté des Habsbourg, de A à Z" [The Franche-Comté region under the Habsburgs, from A to Z]. Echo Sciences (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ "Histoire de la Bourgogne" [History of Burgundy]. Mon coin de Bourgogne (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1992, pp. 229–231

- ^ Borlée, D (2012). "Introduction historique : le duché de Bourgogne au xiiie siècle, contexte "géopolitique"" [Historical introduction: the Duchy of Burgundy in the 13th century, geopolitical context]. La sculpture figurée du xiiie siècle en Bourgogne [Figurative sculpture in 13th-century Burgundy] (in French). Presses universitaires de Strasbourg. pp. 21–30. doi:10.4000/books.pus.13822. ISBN 978-2-86820-478-3.

- ^ Krebs, Víctor Eduardo (1998). ""Translatio Imperii" in the "Cancionero General" and Mexia's "Historia Imperial y Cesarea"". Hispanic Journal. 19 (1): 143–156. JSTOR 44284553. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Duby, Georges (1998). Histoire de France, tome 1 : Le Moyen Âge, 987-1460 [History of France, Volume 1: The Middle Ages, 987-1460] (in French). Hachette Littérature. ISBN 978-2012789289.

- ^ "L'Art de la Guerre au Moyen Âge" [The Art of War in the Middle Ages] (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Lacaze, Yvon; Bernard, Guenée (1971). L'Occident aux XIVe et XVQ siècles. Les États [The West in the 14th and 15th centuries. The States] (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. pp. 283–289. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1992, p. 583

- ^ Fohlen 1992, pp. 603–604

- ^ Fohlen, Claude (1982). Histoire de Besançon [History of Besançon] (in French). Vol. 2: De la conquête française à nos jours. Editions Cêtre. ISBN 978-2901040279.

- ^ Fohlen 1992, p. 682

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 20–21

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 25

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 26–29

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 35–37

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 38

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 41

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 42

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 46

- ^ Windler, C (2010). "De la neutralité à la relation tributaire : la Franche-Comté, le duché de Bourgogne et le royaume de France aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles" [From neutrality to a dependent relationship: Franche-Comté, the Duchy of Burgundy, and the Kingdom of France in the 16th and 17th centuries]. Les ressources des faibles [The resources of the weak] (in French). Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 163–185. doi:10.4000/books.pur.105486. ISBN 978-2-7535-0956-6.

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 55–68

- ^ a b "Les Fortifications de Vauban inscrites au Patrimoine Mondial de l'Unesco" [Vauban's Fortifications, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site] (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Garrigues, Frédéric (1998). "Les intendants du commerce au XVIIIe siècle" [Trade administrators in the 18th century]. Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine (in French). 45 (3): 626–661. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1998.1927. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 238

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 233

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 251–253

- ^ "Chapitre 1 : La Révolution française et l'Empire : une nouvelle conception de la nation" [Chapter 1: The French Revolution and the Empire: a new conception of the nation]. Chemins de Mémoire (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 378

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 379

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 380

- ^ "Thermalisme en Bourgogne-Franche-Comté" [Thermal spas in Burgundy-Franche-Comté]. Patromoine (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 380–382

- ^ "1910 la Crue du siècle à Besançon" [1910: The flood of the century in Besançon] (PDF) (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 487–488

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 489

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 493

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 500

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 501–502

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 505

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 508

- ^ "La répression de la Résistance" [The repression of the Resistance] (PDF) (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 513

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 517

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 518

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 519

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 521

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 523

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 530

- ^ Fohlen 1982, p. 531

- ^ "Décret n°60-516 du 2 juin 1960 portant harmonisation des circonscriptions administratives" [Decree No. 60-516 of June 2, 1960, on the harmonization of administrative districts.]. Legifrance (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Abbiateci, Camille; Ferreira Lopes, Henry; Hitter, Michel; Natter, Sandrine; Pacchin, Fabrice (2017). Catalogue de l'exposition Besançon de papier : Projets d'urbanisme oubliés du XVIIIe à la fin du XXe siècle [Catalogue of the exhibition Besançon de papier: Forgotten urban planning projects from the 18th to the end of the 20th century] (in French). Besançon. pp. 29–37. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fohlen 1992, pp. 536–538

- ^ Fohlen 1982, pp. 570–571

- ^ "Les Prés-de-Vaux, de l'industrie aux loisirs" [Les Prés-de-Vaux, from industry to leisure]. Grand Besancon (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Favereaux, Raphaël. BESANÇON INDUSTRIEL [INDUSTRIAL BESANÇON] (in French). Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- ^ Minovez, J.-M (2019). "La désindustrialisation en longue durée" [Long-term deindustrialization]. 20 & 21. Revue d'histoire (in French). 144 (4): 18–33. doi:10.3917/vin.144.0018. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Thiou, Éric (2006). Les citoyens de Besançon sous l'Ancien Régime (1677-1790) [The citizens of Besançon under the Ancien Régime (1677–1790)] (in French). Versailles: Editions Mémoire et Documents.

- Thiou, Éric (2012). Annuaire des Bisontins à la veille de la Révolution [Directory of Besançon residents on the eve of the Revolution] (in French). Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté.