Georgi Pulevski

Georgi Pulevski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1817 Galičnik, Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia) |

| Died | 13 February 1893 Sofia, Principality of Bulgaria |

| Occupation | Writer and revolutionary |

Georgi Pulevski, sometimes also Gjorgji, Gjorgjija Pulevski or Đorđe Puljevski (Macedonian: Ѓорѓи Пулевски or Ѓорѓија Пулевски, Bulgarian: Георги Пулевски, Serbian: Ђорђе Пуљевски; 1817 – 13 February 1893), was a Mijak[1][2] revolutionary, self-styled lexicographer,[3] self-taught grammarian, historian, textbook writer, ethnographer and poet.[4][5]

Pulevski was born in Galičnik, he trained as a stonemason and later became a self-taught writer. He is known as one of the first authors to express the idea of a distinct Macedonian nation and Macedonian language.[6]

Life

[edit]

Pulevski was born in the village of Galičnik in the Mijak tribal region in 1817.[1] As a seven-year-old, he went to Danubian Principalities with his father as a migrant worker (pečalbar).[7] He was trained as a stonemason.[8] Pulevski did not have a formal education.[9] According to popular legends, Pulevski was engaged as a hajduk in the area of Golo Brdo.[10]

At the age of 45, Pulevski fought as a member of the First Bulgarian Legion in 1862 against the Ottoman siege at Belgrade.[11][12] He also participated in the Serbian–Ottoman War in 1876, and then in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 as part of the Bulgarian Volunteer Corps,[13] which led to the Liberation of Bulgaria; during the latter, he was a voivode of a unit of Bulgarian volunteers,[14][15][16] taking part in the Battle of Shipka Pass.[17] He also participated as a volunteer in the Kresna-Razlog Uprising (1878–79), also referred to as Macedonian Uprising by the insurgents.[13] Pulevski was awarded the Order of St. George for his bravery during the Russo-Turkish War.[18] By decree of Prince Alexander I of Bulgaria at the end of 1879, he was granted financial assistance from the state budget for the development of his literary activity.[19] In an application for a veteran pension to the Bulgarian Parliament in 1882,[20] he expressed his regret about the failure of the unification of Ottoman Macedonia with Bulgaria. In 1883, aged 66, Pulevski received a government pension in recognition of his service as a Bulgarian volunteer. Pulevski settled in the village of Progorelec, near Lom, Bulgaria, where he received gratuitously agricultural land from the state. Later he moved to Kyustendil.[21] In 1888 in Sofia he founded the Slavo-Macedonian Literary Society, which aimed at promoting the Macedonian language and literature, but it was dispersed by the authorities and some of its members were imprisoned.[22][6] Pulevski died in Sofia on 13 February 1893.[23][4]

Works

[edit]

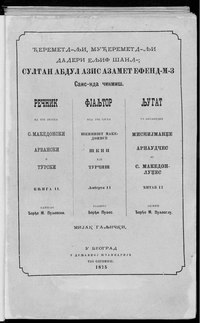

Pulevski authored Dictionary of Four Languages in 1873,[24] where he identified the vernacular Slavic language of Macedonia as "Serbo-Albanian".[25] In 1875, Pulevski published Dictionary of Three Languages (Rečnik od tri jezika, Речник од три језика) in Belgrade, which probably contained the first use of the term "Slavic Macedonian" or "Slav Macedonian" for the vernacular of the Macedonian Slavs.[9] It was a trilingual conversational manual composed in "question-and-answer" style in three parallel columns, in Macedonian, Albanian and Turkish, all three written in Cyrillic.[26] The basis of his language was his native Galičnik dialect but with certain and unsystematic concessions to the central Macedonian dialects.[27] It was an attempt to use a supra-dialectal language. Pulevski stated that the Macedonians were a separate nation and advocated for the Macedonian language.[6] It was the first work that publicly claimed Macedonian to be a separate language.[28] However, there is no exclusive connection of nation, language, territory and statehood in the work, which is different from the ideas in the later work On Macedonian Matters by Krste Misirkov.[29] Pulevski incorporated Kuzman Shapkarev's 1868 primer Elementary Knowledge for Little Children into the work.[27] He acknowledged Macedonia as a multilingual and multiethnic region. The adjective "Macedonian" was not reserved exclusively for the Slavic inhabitants of Macedonia. Per linguist Victor Friedman, Pulevski tried to articulate both the sense of a Macedonian ethnic nationality and the sense of a Macedonian civic national identity.[26]

What do we call a nation? – People who are of the same origin and who speak the same words and who live and make friends of each other, who have the same customs and songs and entertainment are what we call a nation, and the place where that people lives is called the people's country. Thus the Macedonians also are a nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia.[30]

His next published works were a revolutionary poem, Samovila Makedonska (Macedonian Fairy), published in 1878,[31] and a Macedonian Song Book in two volumes, published in 1879, which contained both folk songs collected by Pulevski and some original poems by himself.[23] The former was re-published by Shapkarev in 1882 in the journal Maritsa.[31]

In 1880, Pulevski published Slavjano-naseljenski makedonska slognica rečovska (Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population), a work that is known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. All records of this book were lost during the first half of 20th century and only discovered again in 1953 in Ohrid on the initiative of Blaže Koneski. Since Pulevski was not adequately educated for the task, his grammar remains only an expression of the striving for a Macedonian literary language.[6] Also, it has been characterized as seminal in its signaling of ethnic and linguistic consciousness but not sufficiently elaborated to serve as a codification.[32] In Bulgarian sources his so-called last grammar work is mentioned Jazitshnica, soderzsayushtaja starobolgarski ezik, uredena em izpravlena da se uchat bolgarski i makedonski sinove i kerki; (Grammar, containing Old Bulgarian language, arranged and corrected to be taught to Bulgarian and Macedonian sons and daughters), in which he considered the Macedonian dialects to be old Bulgarian and the differences between the two purely geographical.[33][34] However, the details around it are unclear as to where it is kept or when it is dated.[10]

By 1893, Pulevski had largely completed Slavjanomakedonska opšta istorija (Slavic Macedonian General History), a large manuscript with around 1000 pages.[24] He stated that he wrote the manuscript "in the Slavic-Macedonian dialect (narečenije) so that it could be understood by all the Slavs of the peninsula." He identified the Ottoman Macedonia from which he originated with ancient Macedonia and considered the Macedonian Slavs to be ancient inhabitants of the Balkan peninsula.[24] Pulevski was perfectly consistent with his time's specifics of determining national distinctiveness, emphasizing Slavophilism, with resorting to ancient history as symbols. The idea of direct descendance from ancient Macedonians represented a demonstration of resistance and specific expression of national identity by stressing the glory of ancient Macedonia. Also, much space was reserved for the Nemanjids, as well as Saint Sava, who was described as holy, although by his own words his information was limited to the reproduction of older chroniclers and Serbian historians. For Pulevski, the Serbian tsars, like the Bulgarian tsars, were foreigners, described as ruling over "Macedonian regions."[35] In sum, he was narrating the Slavic peoples' medieval history under titles regarding the history of Bulgaria, Wallachia, and Serbia, but he was stressing his own conclusions concerning ethnicity, thus surely had a clear conception of how Macedonians differed from other Slavs. Overall the work was firmly and directly influenced by Mauro Orbini, amongst the most influential sources, where the pan-Slavic idea and the autochthonism of the Slavs on the Balkans and beyond are asserted.[36] Pulevski also wrote about the places where the Mijaks were concentrated, their migrations and the Mijak region.[4]

Ancestry, identification and legacy

[edit]

According to anthropological study, his surname is of Vlach origin, as is the case with several other surnames in Mijak territory, which contain the Vlach suffix -ul (present in Pulevci, Gugulevci, Tulevci, Gulovci, Čudulovci, etc.) This opens the possibility they are ancestors of Slavicized Vlachs, migrants from an Albanian settlement.[37] It is possible that Pulevski's ancestors settled Galičnik from Pulaj, a small maritime village, near Velipojë, at the end of the 15th century, hence the surname Pulevski.[citation needed]

Pulevski claimed that the Macedonians were descendants of the ancient Macedonians. This opinion was based on the claim that Philip II and Alexander III were of Slavic origin and thus this confirmed the ancient ancestry of the modern Macedonians.[25] These views were criticised by the historian Konstantin Jireček as "foolish".[10] Pulevski considered the Mijaks to be a subgroup of the Macedonians and identified as a "Mijak from Galičnik."[24][2] Pulevski himself, besides as Macedonian, described himself as a "Serbian patriot" in 1874,[25] and also after 1877 he espoused a mixed Macedono-Bulgarian identity as well.[38][39][40] In the Jazitshnica, he viewed Macedonian identity as being a regional phenomenon, similar to Herzegovinians and Thracians.[25] In his grammatical works, he included neologisms that were not included in modern Macedonian and opted for a phonological orthography, inspired by the work of Vuk Karadžić.[41]

Linguist Victor Friedman regards Pulevski as a "complex and modern personality that very well understood the complexities of ethnical-national and civilian-national affiliations in the multilingual and multicultural environment of Macedonia."[29] His work Slavic Macedonian General History was published by the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 2003. A monument of him was placed in the center of Skopje in 2011.[24] In North Macedonia, he is celebrated as a contributor in the "National Rebirth".[13] Despite Pulevski being an early adherent of Macedonism,[42][43] because of his pro-Bulgarian military activity[citation needed], in Bulgaria he is regarded as a Bulgarian.[44][45][46] According to Tchavdar Marinov, of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences,[47][48] there are reasons to interpret the case of Pulevski as a lack of clear national identity by him, while his numerous self-identifications reveal the absence of a clear national identity among portion of the Macedonian Slavs.[49]

List of works

[edit]- Dictionary of three languages - wikisource translation.

- "A dictionary of three languages" on Commons.

- "A dictionary of four languages" on Commons.

- Язичница содержающа старобългарски (македонски) язик, суредена ем исправена за да учат бугарски и македонски синове и кьерки.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Блаже Конески; Димитар Башевски (1990). Ликови и теми. Култура. p. 129. ISBN 978-86-317-0013-1.

- ^ a b Papers in Slavic Philology. University of Michigan. 1984. p. 102. ISBN 9780930042592.

In 1875, Gorge M. Pulevski, who identifies himself as mijak galicki 'a mijak from Galicnik'

- ^ Daskalov & Marinov 2013, p. 315.

- ^ a b c Roth, Klaus; Hayden, Robert, eds. (2011). Migration In, From, and to Southeastern Europe: Historical and cultural aspects. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 113. ISBN 9783643108951.

- ^ Borut Roncevic; Tamara Besednjak Valič, eds. (2024). Sociology and Post-Socialist Transformations in Eastern Europe: A Cultural Political Economy Approach. Springer Nature Switzerland. p. 252. ISBN 9783031655562.

- ^ a b c d Victor A. Friedman: Macedonian language and nationalism during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Balcanistica 2 (1975): 83–98. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Tanas Vražinovski (2002). Rečnik na narodnata mitologija na Makedoncite. Matica makedonska. p. 463. ISBN 9789989483042.

- ^ Naum Trajanovski (2024). A History of Macedonian Sociology: In Quest for Identity. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 8. ISBN 9783031488696.

- ^ a b Alexis Heraclides (2020). The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 9780367218263.

- ^ a b c Срђан Тодоров, О народности Ђорђа Пуљевског. В Етно-културолошки зборник, уредник Сретен Петровић, књига XXIII (2020) Сврљиг, УДК 929.511:821.163 (09); ISBN 978-86-84919-42-9, стр. 133-144.

- ^ Пламен Павлов, Васил Левски и зографите от Галичник. В Годишник на Историческия факултет на Великотърновския университет, (2018) Том 2 Брой 1 Статия 42, стр. 667-673 (672). DOI: https://doi.org/10.54664/THDR1715

- ^ Larry Labro Koroloff, ed. (2021). White Book about the Language Dispute Between Bulgaria and the Republic of North Macedonia. Orbel. p. 43. ISBN 9789544961497.

- ^ a b c Dimitar Bechev (2019). Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 247–248. ISBN 9781538119624.

- ^ Болгарское ополчение и земское воиску (in Russian). Санкт-Петербург. 1904. pp. 56–59.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Дойнов Д. Руско-турската освободителна война и македонските българи.

- ^ Гоцев, Славе. Национално-революционни борби в Малешево и Пиянец 1860–1912. София, Издателство на Отечествения фронт, 1988. с. 96-97.

- ^ Blaže Koneski (1961). Towards the Macedonian Renaissance: Macedonian Text-books of the Nineteenth Century. Institute of National History. p. 86.

- ^ Biljana Ristovska-Josifovska; Dragi Gjorgiev, eds. (2018). The Beginnings of Macedonian Academic Research and Institution Building (19th ‒ Early 20th Century). Skopje: Institute of National History. p. 155.

- ^ Държавен вестник, бр. 12 от 1879 г., с. 2 (Указ № 244 от 10 октомври 1879 г.)

- ^ Glasnik na Institutot za nacionalna istorija, Volume 30, Institut za nacionalna istorija (Skopje, Macedonia), 1986, STR. 295–296.

- ^ Петър Иванов Чолов, Българските въоръжени чети и отряди през ХІХ век. 2003, Акад. изд. проф. Марин Дринов, ISBN 9789544309220, стр. 191.

- ^ Per Srđan Todorov two years later it was replaced by the Young Macedonian Literary Society, although Pulevski most likely was not active in it. For more see: Срђан Тодоров, О народности Ђорђа Пуљевског. В Етно-културолошки зборник, уредник Сретен Петровић, књига XXIII (2020) Сврљиг, УДК 929.511:821.163 (09); ISBN 978-86-84919-42-9, стр. 133-144.

- ^ a b Makedonska enciklopedija: M-Š (in Macedonian). MANU. 2009. p. 1235. ISBN 9786082030241.

- ^ a b c d e Feliu, Francesc, ed. (2023). Desired Language: Languages as objects of national ideology. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 138–141. ISBN 9789027254986.

- ^ a b c d Daskalov & Marinov 2013, p. 316.

- ^ a b Jouko Lindstedt (2016). "Multilingualism in the Central Balkans in late Ottoman times". Slavica Helsingiensia. 49. University of Helsinki: 61–62.

- ^ a b Sebastian Kempgen; Peter Kosta; Tilman Berger; Karl Gutschmidt, eds. (2014). Die slavischen Sprachen / The Slavic Languages. Halbband 2. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 1472. ISBN 9783110215472.

- ^ Mark Biondich (2011). The Balkans: Revolution, War, and Political Violence Since 1878. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780199299058.

- ^ a b Barbara Sonnenhauser (2020). "The virtue of imperfection. Gjorgji Pulevski's Macedonian–Albanian–Turkish dictionary (1875) as a window into historical multilingualism in the Ottoman Balkans" (PDF). Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics. 6 (1). De Gruyter Mouton: 6. doi:10.1515/jhsl-2018-0023.

- ^ Rečnik od tri jezika, p. 48f.

- ^ a b Mitko B. Panov (2019). The Blinded State: Historiographic Debates about Samuel Cometopoulos and His State (10th-11th Century). BRILL. pp. 276–277. ISBN 9789004394292.

- ^ Victor A. Friedman (1995). "Romani standardization and status in the Republic of Macedonia". In Yaron Matras (ed.). Romani in Contact: The History, Structure and Sociology of a Language. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 178. ISBN 9789027236296.

- ^ Kosta T︠S︡ŭrnushanov (1992). Makedonizmŭt i sŭprotivata na Makedonii︠a︡ sreshtu nego. Universitetsko izd-vo "Sv. Kliment Okhridski,". pp. 41–42.

Заключението е ясно — за Пулевски македонският говор е „стар български", а разликата между „болгарски и македонски синове и керки" е чисто географска: за младежи в княжество България и в поробена Македония. (In English: The conclusion is clear - for Pulevski the Macedonian language is "old Bulgarian", and the difference between "Bulgarian and Macedonian sons and daughters" is purely geographical: for young people in the principality of Bulgaria and in enslaved Macedonia.)

- ^ Alexandar Nikolov (2021). "От български автохтонизъм към "антички" македонизъм". In Peter Delev; Dilyana Boteva-Boyanova; Lily Grozdanova (eds.). Jubilaeus VIII: Завръщане към изворите [Jubilaeus VIII: Back to the sources] (in Bulgarian). УИ "Св. Климент Охридски". p. 205. ISBN 978-954-07-5282-2.

В последната си граматика, наречена "Язичница. Содержающа староболгарски язик, а уредена ем исправена, дасе учат болгарски и македонски синове и керки." той представя македонския език като наречие на българския език... (In English: In his last grammar, called "Grammar, containing Old Bulgarian language, arranged and corrected to be taught to Bulgarian and Macedonian sons and daughters." he presents the Macedonian language as a dialect of the Bulgarian language...)

- ^ Stefan Rohdewald (2022). Sacralizing the Nation through Remembrance of Medieval Religious Figures in Serbia, Bulgaria and Macedonia. BRILL. pp. 223–224, 438. ISBN 9789004516335.

- ^ Biljana Ristovska-Josifovska (2019). "A picture of the Slavic world through the prism of a 19th century Macedonian manuscript (transferring knowledge and ideas)". Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana (1): 145–154.

- ^ Karl Kaser (January 1992). Hirten, Kämpfer, Stammeshelden: Ursprünge und Gegenwart des balkanischen Patriarchats. Böhlau Verlag Wien. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-3-205-05545-7.

- ^ Chris Kostov (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996. Peter Lang. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-0343-0196-1.

- ^ Блаже Ристовски, "Портрети и процеси од македонската литературна и национална историја", том 1, Скопје: Култура, 1989 г., стр. 281, 283, 28.

- ^ Етно-културолошки зборник, уредник Сретен Петровић, књига XXIII (2020) Сврљиг, УДК 929.511:821.163 (09); ISBN 978-86-84919-42-9, стр. 133-144.

- ^ Alexis Heraclides (2020). The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 9780367218263.

- ^ Daskalov & Marinov 2013, p. 444.

- ^ Michael Palairet (2016). Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 1, From Ancient Times to the Ottoman Invasions), Volume 1. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 9781443888431.

- ^ Военна история на българите от древността до наши дни, Том 5 от История на Българите, Автор Георги Бакалов, Издател TRUD Publishers, 2007, ISBN 954-621-235-0, стр. 335.

- ^ Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Коста Църнушанов, Унив. изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 40–42.

- ^ Николов, А. Параисторични сюжети: От български автохтонизъм към „антички“ македонизъм. В „Jubilaeus VIII. Завръщане към изворите. Част I“ (2021), София, 8/1, с. 195–208.

- ^ Centre for Advanced Study Sofia (CAS) about Tchavdar Marinov.

- ^ Data on Tchavdar Marinov on the official website of Bulgarian Academy Sciences.

- ^ Daskalov & Marinov 2013, pp. 316–317.

Sources

[edit]- Daskalov, Rumen; Marinov, Tchavdar (2013). Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Georgi Pulevski at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Georgi Pulevski at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Georgi Pulevski at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Georgi Pulevski at Wikiquote