Elaine of Corbenic

| Elaine of Corbenic | |

|---|---|

| Matter of Britain character | |

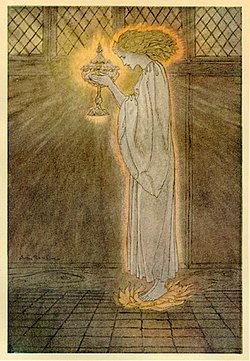

"How at the Castle of Corbin a maiden bare in the Sangreal and foretold the achievements of Galahad" by Arthur Rackham. A 1917 illustration from The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, abridged from Le Morte d'Arthur by Alfred W. Pollard, depicting Lady Elaine carrying the Grail through the halls of King Pelles' palace | |

| First appearance | Vulgate Cycle |

| In-universe information | |

| Occupation | Princess |

| Significant other | Lancelot |

| Children | Galahad |

| Relatives | King Pelles |

| Home | Corbenic, Isle of Joy |

Elaine, also known under many other names and identified as the "Grail Maiden" or the "Grail Bearer",[1] is a character from Arthurian legend. In the Arthurian chivalric romance tradition from the Vulgate Cycle, she is the mother of Galahad by Lancelot, whose repeated rape by her results in his descent into madness. She should not be confused with Elaine of Astolat, a different woman who too fell in love with Lancelot.

Names and origins

[edit]She is variably known as Elaine (Elayne, Helaine, Oisine) or Elizabeth (Eliabel, Elizabel, Elizabet, Heliabel, Helizabel), and is also called Amite (Amide, Amides, Anite, Aude, Enite).[2][3] Her character seems to have been derived from the earlier (and later separate) figure of Percival's sister, and possibly also from that of Arthur's sister.[4] The name "Amite" may furthermore link her to Amice from Meraugis de Portlesguez.[3]

Legend

[edit]She first appears in the Prose Lancelot, a part of the Vulgate Cycle, as an incredibly beautiful woman named Heliabel but known as Amite (in one spelling variant of these names).[5] Her first significant action is showing the Holy Grail to the near-perfect knight, Sir Lancelot.

In the version as told by Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur, based on the later Queste part of the Vulgate Cycle, Lady Elaine's father, King Pelles of the Grail castle Corbenic (Corbenek, Corbin, etc.), knew that Lancelot would have a son with Elaine, and that that child would be Galahad, "the most noblest [sic] knight in the world".[6] Moreover, Pelles claims that Galahad will lead a "foreign country...out of danger" and "achieve...the Holy Grail".[7] However, it has been noted that in older manuscripts Elaine is not named as Pelles' daughter, but merely named alongside the latter. The two figures apparently got mixed up by Malory due to a scribal error in his source.[8]

The sorceress Morgan le Fay is jealous of Elaine's beauty, and magically traps her in a boiling bath. After Lancelot rescues her, Elaine falls in love with him, only to find he is already in love with Queen Guinevere and would not knowingly sleep with another woman. In order to seduce Lancelot, Elaine goes to the sorceress Dame Brusen for help. Dame Brusen gives Lancelot wine and Elaine a ring of Guinevere's in order to trick Lancelot into thinking Elaine is Guinevere.[9] The next morning, Lancelot is most displeased to discover that the woman he slept with was not Guinevere. He draws his sword and threatens to kill Elaine, but she tells him that she is pregnant with Galahad and he agrees not to kill her, but instead kisses her.[10] Lancelot departs, and Elaine remains in her father's castle and gives birth to Galahad.

Thereafter, Elaine comes to a feast at King Arthur's court. Lancelot ignores her when he sees her, making her sad because she loves him. She complains of this to Brusen, who tells her that she will, as Malory tells, "undertake that this night he [Lancelot] shall lie with [her]".[11] That night, Brusen brings Lancelot to Elaine, pretending that it is Guinevere that summons him. He goes along, and once again is deceived into sleeping with Elaine. At the same time, however, Guinevere herself had summoned Lancelot and is enraged to discover that he is not in his bedchamber.[12] She hears him talking in his sleep, and finds him in bed with Elaine. Guinevere is furious with him and tells him she never wants to see him again. Lancelot goes mad with grief and, naked, jumps out a window and runs away.[6] Elaine confronts Guinevere about treatment of Lancelot; she accuses her of causing Lancelot's madness and tells her that she is being unnecessarily cruel. After this, Elaine leaves court.

Time passes in the story, and Elaine next appears when she finds Lancelot insane in her garden.[13] She brings him to the Grail, which cures him. When he regains his mind, he decides to go under a false name with Elaine to the Isle of Joy, where they live together for several years as husband and wife.[14]

Scholarship

[edit]Like the more famous Elaine of Astolat, Elaine of Corbenic is in love with Lancelot, but unlike her she is successful in both bedding and marrying Lancelot. Despite this, she was traditionally overlooked in favor of Elaine of Astolat by literary analysts, perhaps because of the moral ambiguities of her actions.[15]

Roger Sherman Loomis's work The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol draws a connection between the concept of the feminine "Grail-bearer" and the sovereignty goddess of Ireland, Ériu, who grants the chalice to only the worthy. He also saw her derived from the Welsh and Irish goddesses Modron and Dechtire, through the figure and archetype of Morgan.[16]

According to Richard Cavendish, "Lancelot's experiences with Morgan and Elaine form a counter-point to his involvement with Guinevere. The theme of a fay or enchantress falling in love with a knight and trying to keep him her prisoner in the otherworld occurs frequently in the Matter of Britain. Elaine is not described as a fay, but she comes from the otherworldly Grail castle and Lancelot takes refuge with her from the human world in the enchanted Joyous Isle, where there is no time."[17]

Modern portrayals

[edit]Many modern adaptations (such as Arthurian works of Howard Pyle[18] or Parke Godwin'a Firelord and Catherine Christian's The Pendragon[19]) tend to conflate her with the other Elaine, including explicitly in the form of The Lady of Shalott.[20] T. H. White, too, combined the two Elaines into a composite character in The Once and Future King (where he mixed comedy and tragedy for her story), in part due to yet another Elaine connected to Lancelot in Malory as his mother.[21][22] Conversely, it was Arthur's sister also named Elaine that seems to have inspired Robert Jordan the most when he took from Malory's four different Elaines to create The Wheel of Time character of Elayne Trakand.[23]

According to Thelma S. Fenster, "in modern literature, Elaine can be portrayed as naive (Bradley) or sanctimonious (Godwin); sometimes she is one with Elaine of Astolat (Godwin). John Erskine's novel Galahad (1926) portrays this Elaine as clever and determined, bent on having a child with Lancelot."[24] Barbara Tepa Lupack tells the story of 'Elayne of Carbonek' separately from that of Elaine of Astolat in The Girl's King Arthur.[25]

In Bradley's The Mists of Avalon, Elaine is King Pellinore's daughter and Guinevere's cousin who seduces Lancelot with a love potion prepared by Morgaine (Morgan). She and Lancelot have several children in addition to their son Galahad. One of them is Nimue, who becomes a priestess of Avalon and is later used to trick Merlin into causing his death, after which she drowns herself.[26][27]

See also

[edit]- Elaine (legend), the other Arthurian characters known by this name

References

[edit]- ^ Arthurian Women. www.timelessmyths.com. Jimmy Joe, 1999.

- ^ Todd, Henry Alfred (4 September 1918). Romanic Review. Department of French and Romance Philology of Columbia University.

- ^ a b The Evolution of Arthurian Romance i. Slatkine.

- ^ Loomis, Roger Sherman (4 September 1959). "Morgain la fée in oral tradition". Romania. 80 (319): 337–367. doi:10.3406/roma.1959.3184 – via persee.fr.

- ^ Lancelot-Grail: Lancelot, pt. I. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. 4 September 2010. ISBN 9781843842262.

- ^ a b Malory, p. 288.

- ^ Malory, p. 283.

- ^ Bruce, J. Douglas (November 1918). Modern Philology. University of Tennessee.[dead link]

- ^ Malory, pp. 283–84.

- ^ Malory, p. 285.

- ^ Malory, p. 286.

- ^ Malory, p. 287.

- ^ Malory, p. 297.

- ^ Malory, p. 299.

- ^ Sklar, Elizabeth S. "Malory’s Other(ed) Elaine". On Arthurian Women: Essays in Memory of Maureen Fries. Bonnie Wheeler and Fiona Tolhurst. Dallas: Scriptorium Press, 2001. pp. 59–70.

- ^ Loomis, Roger Sherman (27 October 1991). The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691020752.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard (1978). King Arthur and the Grail: The Arthurian Legends and Their Meaning. London: Wedienfled and Nicholson. p. 90.

- ^ "The Lady Elaine the Fair | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu.

- ^ Lacy, Norris J.; Ashe, Geoffrey; Ihle, Sandra Ness; Kalinke, Marianne E.; Thompson, Raymond H. (5 September 2013). "The New Arthurian Encyclopedia: New edition". Routledge – via Google Books.

- ^ Howey, Ann F. (31 July 2020). "Afterlives of the Lady of Shalott and Elaine of Astolat". Springer Nature – via Google Books.

- ^ Sprague, Kurth (28 April 2007). "T.H. White's Troubled Heart: Women in The Once and Future King". DS Brewer – via Google Books.

- ^ Brewer, Elisabeth (28 April 1993). "T.H. White's The Once and Future King". Boydell & Brewer Ltd – via Google Books.

- ^ Livingston, Michael (8 November 2022). "Origins of The Wheel of Time: The Legends and Mythologies that Inspired Robert Jordan". Tor Publishing Group – via Google Books.

- ^ Fenster, Thelma S. (28 April 2000). "Arthurian Women". Psychology Press – via Google Books.

- ^ Ashton, Gail (12 March 2015). "Medieval Afterlives in Contemporary Culture". Bloomsbury Publishing – via Google Books.

- ^ "A Study Guide for Marion Zimmer Bradley's "The Mists of Avalon"". Gale, Cengage Learning. 13 March 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Alamichel, Marie-Françoise; Brewer, Derek (28 April 1997). "The Middle Ages After the Middle Ages in the English-speaking World". Boydell & Brewer Ltd – via Google Books.

Further reading

[edit]- Batt, Catherine. Malory's Morte Darthur: Remaking Arthurian Tradition. New York: Palgrave, 2002. Print. — A monograph comparing the relationship between Lancelot and Elaine in Malory with the French text that he based Morte Darthur on, specifically concerning the circumstances of her rape of Lancelot.

- McCarthy, Terence. Reading the Morte Darthur. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1988. Print. — An edited collection comparing the circumstances of Galahad's birth to the trickery involved in Arthur's conception.

- Scala, Elizabeth. "Disarming Lancelot". Studies in Theology Autumn 2002: 380–403. Magazine. — An article concerning Elaine's power over Lancelot in regards to her seduction.

- Sklar, Elizabeth S. "Malory’s Other(ed) Elaine". On Arthurian Women: Essays in Memory of Maureen Fries. Bonnie Wheeler and Fiona Tolhurst. Dallas: Scriptorium Press, 2001. 59–70. Print. — An analysis of Elaine of Carbonek’s dismissal from scholarly works because of her complex role in Arthurian literature.

- White, Terence Hanbury. The Once and Future King. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1958. Print. — A monograph including modern depiction of Lancelot and Elaine's relationship.

- Suard, François. "The Narration of Youthful Exploits in the Prose Lancelot". Trans. Arthur F. Crispin. The Lancelot-Grail Cycle: Texts and Transformations. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994. 67–84. Print. — A description of Galahad's conception and birth.

External links

[edit]- “Arthurian Women.” Jimmy Joe, 1999. Web. 24 June 2006. An encyclopedia article covering her name, beauty, and genealogy.

- “Houses of the Grail Keeper and the Grail Hero.” Jimmy Joe, 1999. Web. 24 June 2006. – An article tracing Elaine of Carbonek’s lineage back to Joseph of Arimathea.

- University of Idaho, 1997. Web. 04/1999. “The Elaines.” – An article detailing the unification of holy bloodlines that occurred when Elaine coerced Lancelot into having sex with her and the subsequent conception of Galahad.