El Apóstol

| El Apóstol | |

|---|---|

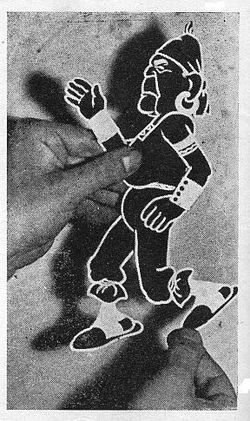

The advertising flyer for the film | |

| Directed by | Quirino Cristiani |

| Written by | Alfonso de Laferrére |

| Produced by | Federico Valle |

| Animation by | Quirino Cristiani |

| Backgrounds by | Andrés Ducaus |

Release date |

|

Running time | 70 minutes |

| Country | Argentina |

| Language | silent |

El Apóstol (English: The Apostle) was a 1917 lost Argentine animated film, directed and produced by Quirino Cristiani and Federico Valle respectively. Historians consider it the world's first animated feature film. Production began after the success of Cristiani and Valle's short film La intervención a la provincia de Buenos Aires, lasting either less than ten months or twelve months; accounts differ. Its script was written by Alfonso de Laferrére, the background models of Buenos Aires were created by Andrés Ducaud, and the initial character designs were drawn by Diógenes Taborda.

El Apóstol is a satire based on Argentina's then-president Hipólito Yrigoyen. In the film, Yrigoyen dreams about going to Mount Olympus and discussing politics with the gods before using one of Zeus's lightning bolts to cleanse Buenos Aires of corruption. Well received at the time in Buenos Aires, it was not distributed beyond that city. The film was destroyed in a 1926 fire in Valle's studio.

Plot

[edit]Argentine president Hipólito Yrigoyen dreams about ascending to Olympus dressed as an apostle. He speaks with the gods about the deeds and misdeeds of the porteños, and how they laugh at him and every political program he sets up. A few congressmen appear, and express their positions. Yrigoyen discusses the level of chaos in the capital administration with the gods, and the government's financial situation. After the discussion, Yrigoyen asks Zeus for lightning bolts to cleanse Buenos Aires of immorality and corruption. Zeus grants his request; lightning bolts consume the city's main buildings, and Yrigoyen awakens.[1][2]

Production

[edit]

Federico Valle was an industrial-film producer who produced a newsreel, Actualidades Valle.[3][4] He hired Quirino Cristiani, known at the time for caricatures in daily newspapers, to help animate an experimental political vignette for Valle's newsreel. They made La intervención a la provincia de Buenos Aires (English: Intervention in the Province of Bueno Aires), a one-minute sketch ridiculing governor Marcelino Ugarte,[3] using paper-cut animation,[5] which Cristiani learned from a film by Émile Cohl.[3][6] Although many Argentine sources identify the release of La intervención a la provincia de Buenos Aires as 1916, its actual release date is unknown.[7]

After the success of La intervención a la provincia de Buenos Aires,[8] Valle began working on the full-length film El Apóstol,[3] which satirized President Yrigoyen,[9] who won the 1916 presidential election as part of the Radical Civic Union and had a reputation for lengthy speeches and demagoguery.[10] Valle hired Alfonso de Laferrére to write the script and Cristiani to serve as the principle animator. Upon Cristiani's request for aid due to the meticulous nature of animation, Valled hired Andrés Ducaus to build three-dimensional models of buildings in Buenos Aires.[5][11] The animation method would be identical to that of La intervención a la provincia de Buenos Aires.[5]

To attract publicity, Valle hired the popular cartoonist Diógenes "El Mono" Taborda.[12][13] Taborda liked the idea of bringing his caricatures to life and gave Cristiani sketches of the characters.[13] Although Cristiani thought they were good, they were too rigid and detailed for him to animate.[13] Taborda left the production, daunted by the amount of work needed to complete the film, but allowed Cristiani to make his drawings simpler and easier to animate.[14]

It is unknown exactly how long El Apóstol took to produce, but it was quick for an animated film.[15] According to different accounts, production took either a year or less than ten months.[9][15] Filming was done in the studio Talleres Cinematográficos, using self-made voltaic arc lamps set up by Cristiani as artificial light.[16] A total of 58,000 frames were filmed, clocking in at one hour and ten minutes.[17] The destruction of Buenos Aires scene at film's conclusion used the three-dimensional models of the city created by Ducaus.[10]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

El Apóstol was released on November 9, 1917, at the Cine Select-Suipacha.[18] The film was successful in Buenos Aires,[19] with newspapers favorably reviewing the film. Crítica, La Nación, and La Película considered El Apóstol a cinematic advancement, and La Razón considered it good satire.[20] The destruction of Buenos Aires near the end of the film was considered its most impressive scene.[21] While El Apóstol was initially paired with other films during cinema showings, success among the general public in Buenos Aires led to theater managers running repeated showings of the film in a single days. El Apóstol screenings lasted for six months[22] before it was banned by the Buenos Aires town council for being a caricature of a current political situation.[9] Because it appealed primarily to Buenos Aires residents, it was not distributed beyond its initial location, making it obscure.[23]

Cristiani reportedly received little credit for the film; he was paid a meager 1,000 pesos (Equivalent to ~US$20 in 1917, or ~US$491 in 2024) and received minimal credit in the intro.[24] Cristiani left Valle due to his interference with his work such as hiring unwanted collaborators,[25] and Valle never made another animated feature film.[26] A 1926 fire destroyed Valle's film studio, including his equipment[27] and the only known copy of El Apóstol. It is now a lost film.[1][28] Cristiani worked on many animated short films during his career[9][29] and at least two other animated feature films: Sin dejar rastros (Without Leaving a Trace)[25] and Peludópolis.[30] Cristiani retired from the animation industry in 1941.[28] El Apóstol became known as the first animated feature-length film.[18][29] Available information about El Apóstol comes from Argentine film records, the Cristiani family archives, and Cristiani's memories as recorded by Giannalberto Bendazzi.[1][17][31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Bendazzi 1995, p. 49.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b c d Bendazzi 1995, p. 48.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Rist 2014, p. 193.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 22.

- ^ Beckerman 2003, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Finkielman 2004, p. 20.

- ^ a b Pallant 2017, p. 38.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 23.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Bendazzi 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Bendazzi 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, pp. 29, 31.

- ^ a b Bendazzi, Giannalberto (December 1984). "Quirino Cristiani, The Untold Story of Argentina's Pioneer Animator". Graffiti. Translated by Solomon, Charles. Archived from the original on October 25, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019 – via Animation World Network.

- ^ a b Bendazzi 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Zeke (February 26, 2015). "A Quick History of Animation". New York Film Academy. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 36.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 40.

- ^ a b Bendazzi 2017, p. 44.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 193.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 54.

- ^ a b Rist 2014, p. 194.

- ^ a b Maher, John (October 8, 2020). "10 Tragically, Irretrievably Lost Pieces of Animation History". Vulture. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Bendazzi 2017, p. 76.

- ^ Sisterton, Dennis (March 28, 2017). "Magic Wilderness: El Apóstol & Peludópolis". Skwigly. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Barnard, Timothy (2013). South American Cinema: A Critical Filmography, 1915-1994. Routledge. ISBN 9781136545559.

- Beckerman, Howard (2003). Animation: The Whole Story. Allworth Press. ISBN 9781581153019.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (1995). Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation. Translated by Taraboletti-Segre, Anna. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253209375.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (2017). Twice the First: Quirino Cristiani and the Animated Feature Film. CRC Press. ISBN 9781351371797.

- Finkielman, Jorge (2004). The Film Industry in Argentina: An Illustrated Cultural History. McFarland. ISBN 9780786416288.

- Pallant, Chris (February 23, 2017). "The Stop-Motion Landscape". Animated Landscapes: History, Form and Function. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781501320118.

- Rist, Peter (2014). Historical Dictionary of South American Cinema. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780810880368.

External links

[edit]- 1917 films

- 1917 animated films

- 1917 lost films

- 1910s stop-motion animated films

- 1910s political films

- Animated feature films

- Argentine animated films

- Argentine silent films

- Argentine black-and-white films

- Argentine satirical films

- Political satire films

- Cutout animation films

- Films about fires

- Films about presidents

- Cultural depictions of politicians

- Cultural depictions of Argentine people

- Animation based on real people

- Animated films based on classical mythology

- Films directed by Quirino Cristiani

- Films set in Buenos Aires

- Films set in heaven

- Lost animated films

- 1910s Spanish-language films

- Lost Argentine films