Draft:Melnykites

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take a week or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 481 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

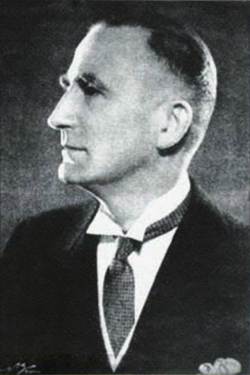

Melnykites (Ukrainian: Мельниківці, romanized: Melnykivtsi) is a colloquial name for members of the OUN-M or OUN(m), a faction of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) that arose out of a split with the Banderite faction in 1940. The term derives from the name of Andriy Melnyk (1890–1964), the leader of the OUN formally elected to the post in August 1939 following the May 1938 assassination of the previous leader, Yevhen Konovalets, by the NKVD.

Since 2012, the OUN(m) has been led by activist and historian Bohdan Chervak.

Background

[edit]A veteran of the First World War (1914-1917) and the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921) serving as a senior officer, otaman, and the chief of staff for the Sich Riflemen and later the wider Ukrainian People's Army (UNA), Andriy Melnyk, retaining the rank of colonel, was a founding member of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in 1929, as well as having cofounded its predecessor, the Ukrainian Military Organisation (UVO) in 1920.[1]

Despite having largely stepped back from UVO and OUN operations since his imprisonment by the Polish authorities from 1924-28 whereafter he chaired the OUN Senate, a consultative body that sought to provide ideological guidance, Melnyk was selected by the Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists (the OUN's executive command in exile, sometimes referred to as the Provid, and hereon the PUN) after they struggled to select a leader from their ranks in the aftermath of former UVO and OUN leader Yevhen Konovalets's assassination in May 1938, while Melnyk claimed to have received a letter from Konovalets naming him as his preferred successor.[1]

Melnyk was chosen for his more moderate and pragmatic stance; his supporters generally favoured Vyacheslav Lypynsky's conservatism and admired Mussolini's fascism but distanced themselves from Dmytro Dontsov's contemporary writings and Nazism.[1][2] Melnyk's supporters were mostly made up of an older, more cautious generation that largely composed the exiled PUN and had spent their formative years under the auspices of the Ukrainophilism movement with many having fought in the failed independence war whereafter Ukrainophilism was supplanted among radical nationalists, as opposed to the moderate Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance, by Dontsov's brand of integral nationalism, considered by many scholars to be by this point a form of fascism.[1][2][3][4] A younger and more radical faction of the OUN heavily inspired by Dontsov's works and the National Socialist movement were dissatified with Melnyk's leadership and demanded a more charismatic and radical leader.[2] This generational divide, that had been largely up until then successfully managed by Konovalets's leadership, led the younger more radical generation to coalesce around Stepan Bandera, the previous head of OUN propaganda from 1931-34 who was in prison for his role in the assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki and had attained notoriety for the publicity that arose from the 1935 Warsaw and 1936 Lviv trials.[5]

Prior to the split, Melnyk and Bandera had been recruited into the Abwehr from 1938 onwards, assigned the codenames 'Consul I' and 'Consul II' respectively, whereby the PUN collaborated with Nazi military intelligence to plan the largely aborted OUN Uprising of 1939 that sought to disrupt the Polish rear during a German invasion.[6][7] In a Vienna meeting in late 1939, Melnyk was directed by Wilhelm Canaris to oversee the drafting of a constitution for a Ukrainian state which was completed by Mykola Stsiborskyi, the OUN's chief theorist who had at one time advocated for the assimilation of Ukrainian Jews, and encompassed the establishment of a totalitarian state under a Vozhd (Col. Melnyk) with distinct and ambiguous citizenship laws for the Ukrainian-Jewish population.[8]

Split with the Banderite faction

[edit]In January 1940, and following his release from prison during the Nazi-Soviet partition of Poland that unified Ukrainian lands under the Soviet Union, Bandera travelled to Rome with a series of demands, among them the replacement of certain members of the PUN with members of the younger generation, though this was rejected by Melnyk and Bandera subsequently made a challenge to the PUN on 10 February by establishing a 'revolutionary' Provid in Nazi-occupied Kraków and turned down Melnyk's offer to make him head of the home command in Soviet-controlled Galicia.[8][1][a] On April 5, Melnyk and Bandera met again in Rome in a final unsuccessful attempt to resolve the growing divide between the two emerging factions with the OUN subsequently fracturing into two rival organisations: the Melnykites (Melnykivtsi or the OUN(m)) and the Banderites (Banderivtsi or the OUN(b)), with Melnyk continuing efforts in vain to try to repair the schism.[9][10][11]

Of the three PUN members that Bandera demanded be replaced, he and his followers' accusations encompassed Omelian Senyk losing OUN documents to the Czech and subsequently Polish police as chief administrative officer to Konovalets in the run up to Bandera's and fellow OUN members' trials in 1935 and 1936, Mykola Stsiborskyi (the OUN's chief theorist) having a debate in passing with a Communist agent that attempted to recruit him, and Yaroslav Baranovsky's brother being an agent for the Polish police.[1][b]

Latent tensions about the ethnic background of Richard Yary, a central member of the OUN(b) behind the split, and the only member of the PUN to join it, whose wife was born an Orthodox Jew and who had been the subject of allegations of corruption dating back to UVO cooperation with Weimar Germany, and the personal life of Mykola Stsiborskyi, whose third wife was purportedly Jewish, descended into acrimony between the two factions that would continue to trade barbs and rebuttals well into July 1941, regularly publishing polemics throughout the early 1940s.[8] It's possible that an alleged spat between Stsiborskyi and Yaroslav Stetsko whereby Stsiborskyi dismissed Stetsko from his duties in preparation for the 1939 Second Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists held in Rome, asserting that he was unable to complete his duties, contributed to the tensions between Bandera's supporters and the PUN.[1] In an August 1940 letter addressed to Melnyk, Bandera stated that he would accept the colonel's authority if he removed 'traitors' from the PUN, especially Stsiborskyi whom he lambasted for possessing an absence of "morality and ethics in family life" and for marrying a "suspicious" Russian-Jewish woman.[8]

In March 1941, the Banderite faction held the Second Grand Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists in Nazi-occupied Kraków where Bandera was proclaimed Providnyk of the OUN (technically the OUN(b)), having declared the original 1939 Second Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists that had officially ratified Melnyk as leader to have been arear of internal laws.[1] Though Melnyk received widespread support among Ukrainian émigrés abroad, Bandera's position on the ground in Western Ukraine and the demographics of his base meant that he gained control of the vast majority of the local aparatus in the region.[12][13] The OUN(m) also retained the support of Ukrainian nationalists in Bukovina, which had been annexed by the Soviets in mid-1940 and later recaptured by German and Romanian forces in mid-1941, providing the organisation with approximately 500 much-needed generally younger members.[1] Ironically, effective Soviet repression in Central and Eastern Ukraine meant that most of the Ukrainians living in these regions were unaware of the split in the OUN, benefitting the more active Banderites in their battle for legitimacy.[10][1]

The Second World War and collaboration with the Nazis

[edit]From their bases in Berlin and Kraków, the OUN(m) and OUN(b) created marching groups under the Abwehr, the Bukovinian Battalion by the OUN(m) (styled off of its namesake during the 1917-1921 independence war) and the Nachtigall and Roland battalions by the OUN(b), intending to follow the Wermacht into Ukraine during the June 1941 German invasion fo the Soviet Union to recruit supporters and set up local governments.[11][14] In contrast to the OUN(b) that unilaterally proclaimed an independent Ukrainian state in Lviv on 30 June, the OUN(m) avoided such actions and sought to gain favour with the Nazi authorities and the Wermacht, serving as interpreters and advisors, though Melnyk himself would have his movements restricted to Berlin in mid-1941.[1][15][16] The day after the Banderite proclaimation, 3,000 bodies were found in basements around Lviv seemingly killed by the NKVD, leading to anti-Jewish pogroms in which some Melnykites participated. Having led the first OUN(m) expeditions into Central and Eastern Ukraine and set up an administration in Zhytomyr, supplanting an embryonic OUN(b) administration, Mykola Stsiborskyi and Omelian Senyk, both key members of the PUN, were assassinated in the city on 30 August, gunned down by Stephan Kozyi, allegedly an OUN(b) member from Western Ukraine whereafter the Nazi authorities began a wider crackdown on the OUN(b).[17][1][c] Shortly before they were killed, Stsiborskyi and Senyk met with Taras Bulba-Borovets in Lviv and agreed to send him a number of trained officers for the UPA-Polissian Sich.[1][d]

Despite a secret directive by OUN(b) leadership not to allow Melnykite leaders to reach Kyiv (which Melnykites referred to as a 'death sentence'), a group of OUN(m) members reached Kyiv before the Banderites in the days following the city's capture by the Germans on 19 September 1941, supplemented by an expeditionary group including PUN members, whereby they established the Ukrainian National Council (UNRada), modelled off of its namesake under the Austro-Hungarian Empire on 5 October and intended to serve as the basis for a future Ukrainian state, also setting up a base in Rivne, the capital of the Reichcommissariat of Ukraine under Erich Koch.[1][15][18][2] In coordination with the PUN, part of this group joined the Propaganda Abteilung U (Propaganda Division for Ukraine), a division of the Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops, and later set up the newspaper Ukrainske slovo ('Ukrainian Word' and hereon US) in Kyiv that had a circulation of over fifty thousand and propagandised the OUN(m), Ukrainian nationalism, and the Nazi 'liberation'.[15][1] The Bukovinian Battalion arrived in Kyiv in late September, subordinating themselves to the UNRada, and were implicated in the Holocaust with historical accounts evidencing that they guarded and sorted the belongings of Jews murdered at Babyn Yar.[14][19] Though the Melnykites intitially enjoyed support against the Banderites from the German military authorities, the OUN(m)'s growing strength in Central and, to a lesser degree, Eastern Ukraine whereby they came to control a number of local administrations, police forces, and newspapers across the region and the incompatibility of Ukrainian statehood with Nazi designs on the region led the SS and Nazi Party officials to overrule the Wermacht with the UNRada dissolved in mid-November, effectively liquidating the Bukovinian Battlion whose members were dispersed with many merged into auxillary police battalions, forming the core of, among others, the Schutzmannschaft Battalion 118 in the spring of 1942 that would later be implicated in the 1943 Khatyn Massacre.[1][19][14]

On 21 November, 1941, Melnykites held a rally in the town of Bazar commemorating members of the UNA executed by the Bolsheviks 20 years earlier at the end of the Second Winter Campaign.[15] Between several hundred and several thousand people attended the event with speeches given by OUN(m) representatives and employees of the local occupation authorities while shouts of "Glory to Ukraine!" and "Glory to the leader Andriy Melnyk!" were heard alongside a choir-sung rendition of "Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished" (dating back to 1862, adopted by the Ukrainian People's Republic in 1917, and which would provide the basis for the modern Ukrainian national anthem).[15] Large scale arrests took place in Korosten Raion immediately after the rally ended whereafter they were transported to a former NKVD prison in Bobrynets and interrogated. About 200 Melnykites were arrested over the next few days with several dozen of the arrested OUN(m) activists and sympathisers executed by firing squad in early December.[15] Having been briefly arrested by the SD on 20 December, Osyp Boydunyk travelled to Berlin, assisted by Petro Voinovsky, commander of the Bukovinian Battalion, where he informed the PUN and Melnyk of the situation in Ukraine who subsequently sent letters to Nazi officials, including Adolf Hitler, protesting the arrests and attempting to secure their release.[15]

On 12 December, the editorial staff of Ukrainske slovo were arrested by the SD, with the newspaper publishing under the name Nove ukrainske slovo (New Ukrainian Word) from 14 December onwards, abandoning the pro-Melnykite editorial agenda.[15][1] Though initially released, they were eventually executed in early January 1942, reportedly for 'failing to follow orders' with the same anonymous 1943 German report, historian Yuri Radchenko asserts that this was most likely authored by an employee of the Kyiv SD, alleging that an initial investigation of their offices discovered pro-Western Allies sympathies and chauvinist attitudes and that subsequent interviews of the editorial staff's circle provided a large amount of incriminating material against them.[15]

After the disappearance of the US editorial staff, many Melnykites, including Oleh Olzhych who had only escaped detention due to the local police being controlled by the OUN(m), left Kyiv for Western Ukraine though some remained, poetess Olena Teliha among them.[15][1] Between 6-9 February, 1942, several dozen OUN(m) members, Teliha and her husband among them as well as OUN(m) sympathiser and mayor of Kyiv Volodymyr Bahaziy, were arrested in Kyiv and held in an SD prison at 33 Korolenko Street, Boyarka.[20][15] A 4 February report prepared by the SD had portrayed the OUN(m) as enemies of Nazi Germany, in contact with Great Britain and collaborating with the Bolshevik underground.[15] Hearing of Teliha's arrest, Ulas Samchuk turned to an acquaintance in the Rivne SD, SS-Hauptscharführer Albert Müller, who agreed to go to Kyiv in an effort to secure her release.[15] Melnykites subsequently petitioned Alfred Rosenberg and his deputies, whereafter the Kyiv SD was ordered not to execute the arrested and a commission was sent from Berlin that secured the release of some of the prisoners, though the remaining Melnykites that had arrived in autumn 1941 had already been shot.[15] OUN(m) members' memoirs written in the 1970s-1990s generally claim that these individuals were executed at Babyn Yar, though this is disputed by modern historians such as Per Anders Rudling and Yuri Radchenko, with Radchenko asserting that, in the absence of supporting evidence, they could have been executed at many places in Kyiv and not necessarily Babyn Yar with Teliha most likely taking her own life in prison following brutal beatings and torture based on the accounts of a fellow inmate at 33 Korolenko Street and the succeeding mayor of Kyiv, indirectly supported by other evidence.[3][19]

OUN(m) members assumed a semi-legal status in Ukraine, wary of further repressions, and attempted to preserve their positions in local police forces and self-government structures without provoking the Nazi authorities.[15][19] On 21 March, Ulas Samchuk was arrested in Rivne by the SD, though he was released in April, as part of a wider crackdown in the spring of 1942 that included OUN(m) members in the SS such as Stepan Fedak (Melnyk's brother-in-law), who was also later released after a year in prison and subsequently joined the SS Galicia Division.[19] Further significant waves of repressions and executions against Melnykites occurred in late 1942 and throughout 1943 in different parts of Ukraine with some rank-and-file members of the OUN(m) setting up partisan units to resist the Germans in response, such as one that was active from March-August 1943 in Kremenets Raion following the execution of a group of local OUN(m)-affiliated intellectuals.[19] Over the course of the Nazi occupation and from the start of Nazi repressions, some Melnykite activists were sent to the Syrets and Janowska concentration camps.[15][19]

PUN member Yaroslav Baranovsky was assassinated by the OUN(b) in Galicia on 11 May 1943.[1][21] Though they for the most part involved OUN(b) members while the Melnykites were practically marginalised, some OUN(m) members were implicated in the 1943 Galicia-Volhynian Massacres.[3][5] A leaflet disseminated in 1944 by Melnykites among the civilians of Volhynia blamed the Banderite faction for the failure of the nationalist movement, condemning them for provoking the Nazi authorities, the "senseless and murderous violence towards the Polish civilian population", and "most of all" acts of violence against non-conforming Ukrainians by the OUN(b) and the UPA.[22]

Amid the Allied bombing of Berlin, Melnyk and his wife travelled to Vienna in late 1943, being arrested by the Gestapo in late January 1944 after which Oleh Olzhych became acting head of the PUN.[16] Melnyk was transported first to a dacha in Wannsee to be interrogated, then in March to the alpine settlement of Hirschegg where he was held as a Sonderhaftling (special prisoner) at the Ifen Hotel, and subsequently to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in July, later being moved on 4 September to a Zellenbau isolation cell.[16] PUN member Roman Sushko, a colonel in the UNA and cofounder of the UVO, had been assassinated in Lviv on 12 January, most likely by OUN(b) members.[23][1] Olzhych was arrested by the SD in Lviv on 25 May and transported first to Berlin and then to Sachsenhausen in early June where he was kept in a Zellenbau cell for death row prisoners.[16] Having been frequently interrogated and badly beaten over the next several days, which was unusual compared to the treatment of his neighbouring Ukrainian nationalists, Olzhych was found dead in his cell on 9 June— accounts on how he died vary between him succumbing to his injuries or taking his own life by hanging.[16][e] By autumn 1944, many OUN(m) members across Europe, including nearly the entire leadership bar former UNA generals Viktor Kurmanovych and Mykola Kapustiansky, were being held in various German prisons, with Melnyk claiming to a fellow prisoner at the Ifen Hotel to have been interrogated for a list of such members when he was held in Wannsee.[16][24]

Suffering from manpower shortages, a group of Nazi Party officials and SS officers endeavoured to set up the Ukrainian National Committee to negotiate and coordinate support for the retreating Wermacht with a broad spectrum of imprisoned Ukrainian nationalist leaders released and taken to Berlin, including Melnyk and the OUN(m) leadership in October 1944.[16] According to the OUN(m)'s internal documentation, 43 Melnykites were released, Voinovsky, PUN member Dmytro Andriievsky, and Rozbudova natsiï editor Volodomyr Martynets among them, while a further 179 remained in various prisons and concentration or labour camps.[16] Melnyk and his supporters however were dissatisfied with the progress and value of these negotiations and instead organised a meeting in Berlin in January 1945 whereupon it was decided that OUN(m) members would meet the Allied advance and seek to familiarise the Western Allies with the Ukrainian independence movement, successfully petitioning Allied military administrations to allow Ukrainians to be separated from Poles and Russians and allowed to display the blue-and yellow flag.[25] Historian Yuri Radchenko estimates that between several hundred and one thousand OUN(m) members were killed by the Nazis over the war.[16]

Post-WW2 and the Cold War era

[edit]The OUN(m) distributed anonymous pamphlets as early as 1946 in west German Ukrainian displaced persons camps that sought to rewrite the history of the war into a nationalist propagandist narrative, exclusively victimising and lionising the organisation for the brutal repression many of its members endured and glossing over its complicity in war crimes and much of its collaboration with the Nazis.[15] Historian Yuri Radchenko asserts that these efforts were instrumental in popularising myths surrounding the OUN(m) in the diaspora and newly independent Ukraine.[15][19]

Sometimes going by the name 'OUN Solidarists' (OUNs), the OUN(m) reoriented to an ideology of conservative corporatism, discarding many of its prior fascist elements at its Third Grand Congress held on 30 August 1947 whereby the leader was to be held accountable by a congress every three years and the principles of freedom of conscience, press, speech, and political opposition introduced.[26][27][28] At its Seventh Grand Congress in 1970, the OUN(m) rejected radical nationalism and embraced political pluralism.[28] After Melnyk's death in 1964, leadership of the PUN passed on to Oleh Shtul (1964-1977), Denys Kvitkovsky (1977-1979), and Mykola Plaviuk (1979-2012) who also led the government of the (1917-1921) Ukrainian People's Republic in exile.[29]

According to declassified CIA reports from 1952 and 1977, the less intellectual and "radically outmoded" Banderite émigré organisations struggled to build influence on the ground in the Ukrainian SSR whereas Melnykite organisations would go on to establish contacts with Ukrainian dissidents and publish dissident works such as the 1968 Chornovil Papers and five volumes of The Ukrainian Herald.[13][30] Historian Georgiy Kasianov argues that, during perestroika in the late 1980s, nationalist émigré groups exported a cultural memory to Soviet Ukraine of the OUN as 'freedom fighters against two totalitarian regimes', leading to the proliferation of so-called 'memory politics' in independent Ukraine— though these efforts principally concerned the rehabilitation and enobling of Bandera, the OUN(b), and the UPA given that they best embodied this historical narrative.[31]

Post-Soviet Ukraine

[edit]Myroslav Yurkevich, of the University of Alberta, wrote in the third volume of the Encyclopaedia of Ukraine published in 1993: "The power and influence of the OUN factions have been declining steadily, because of assimilatory pressures, ideological incompatibility with the Western liberal-democratic ethos, and the increasing tendency of political groups in Ukraine to move away from integral nationalism."[27] That year, the OUN(m) registered in Ukraine as a non-governmental organisation, adopting a national democratic programme at its May 1993 Twelfth Grand Congress held in Irpin.[31][28] The OUN(m) subsequently set up the Olena Teliha Publishing House in Kyiv the following year that continues to publish Ukrainske slovo[f] as a weekly magazine as well as the scientific journal Rozbudova Derzhavy ('Building the State') and a large number of Melnykite legacy works and memoirs.[31][32]

In mid-2007, the National Bank of Ukraine released two commemorative coins for OUN(m) members Olena Teliha and Oleh Olzhych.[33][34]

After Plaviuk's death in 2012, leadership of the PUN and OUN(m) passed on to Ukrainian activist and historian Bohdan Chervak [ukr] (chief editor of Ukrainske slovo since 2001) who was appointed by President Petro Poroshenko in 2015 as First Deputy Head of the State Committee for Television and Radio-broadcasting, retaining the position as of July 2025.[35] In 2017, he was appointed by Poroshenko to the planning committee for the development of the site of Babyn Yar alongside Volodymyr Viatrovych and Jewish community leaders, subsequently criticising plans to build a Holocaust museum there on the grounds that there was inadequate recognition of OUN members killed by the Nazis, writing in a Facebook post:

“Do these people realise that Babyn Yar is also the place that is inseparable from the historical memory of the Ukrainian nation? It is here where the memory of the OUN groups and of Olena Teliha is preserved."[36][37]

In 2019, Chervak ran for the Verkhovna Rada as the 49th party list candidate for the Svoboda party though the party received 2.15% of the vote, below the 5% threshold needed for party list candidates to begin to be awarded seats based on proportional representation.[38]

Pro-Melnykite organisations that still exist in the diaspora today include the Ukrainian National Federation of Canada, the Organisation for the Rebirth of Ukraine (ODVU) in the United States, the Union for Agricultural Education in Brazil, the Vidrodzhennia society in Argentina, the Ukrainian National Alliance in France, and the Federation of Ukrainians in the United Kingdom.[29]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Accounts of the remaining demands, written postwar, vary.

- ^ Bandera and his followers claimed that these members were compromised by hostile spy networks. John Alexander Armstrong asserts that these claims were less than plausible.

- ^ It is also sometimes hypothesised that Stephan Kozyi, who was killed after a pursuit by German and Ukrainian police and having been a former communist, was an NKVD agent though this isn't supported by the available evidence.

- ^ Though sharing the same name, this is a different UPA to the one formed later under the OUN(b) in October 1942.

- ^ OUN(m) members' memoirs claim that Olzhych had been caught compiling a record of Nazi warcrimes when the SD searched his living quarters, though these sources are generally not considered reliable by modern historians. Radchenko speculates that Olzhych's comparatively severe treatment was likely due to the discovery of a real or imaginary connection to the Western Allies given that the Normandy Landings had just occurred at the time.

- ^ Since 1915, there have been, and still are, several publications by this name of varying alignments but typically in the Ukrainophile or nationalist tradition.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Armstrong, John (1963). Ukrainian Nationalism (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Erlacher, Trevor (2021). Ukrainian Nationalism in the Age of Extremes: An Intellectual Biography of Dmytro Dontsov. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2d8qwsn. ISBN 978-067-425-093-2. JSTOR j.ctv2d8qwsn.

- ^ a b c Rudling P.A. (2011). "The OUN, the UPA and the Holocaust: A Study in the Manufacturing of Historical Myths". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies. 2107. Pittsburgh: University Center for Russian and East European Studies. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ Kurylo T., Khymka I. (2011). "How did the OUN treat the Jews? Reflections on the book by Volodymyr Viatrovych". Ukraina Moderna (in Ukrainian). 13 (2): 252–265. Retrieved 27 June 2025.

- ^ a b Rossoliński-Liebe, Grzegorz (2014). Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist. Fascism, Genocide, and Cult. Stuttgart: Ibidem Press. ISBN 978-3-8382-0604-2.

- ^ "Nuremberg - The Trial of German Major War Criminals (Volume VI)". Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

Stolze's testimony of 25th December, 1945, which was given to Lieutenant-Colonel Burashnikov, of the Counter-Intelligence Service of the Red Army and which I submit to the Tribunal as Exhibit USSR 231 with the request that it be accepted as evidence. [...] 'In carrying out the above-mentioned instructions of Keitel and Jodl, I contacted Ukrainian Nationalists who were in the German Intelligence Service and other members of the Nationalist Fascist groups, whom I enlisted in to carry out the tasks as set out above. In particular, instructions were given by me personally to the leaders of the Ukrainian Nationalists, the German Agents Myelnik (code name 'Consul I') and Bandara to organise, immediately upon Germany's attack on the Soviet Union, and to provoke demonstrations in the Ukraine, in order to disrupt the immediate rear of the Soviet Armies, and also to convince international public opinion of alleged disintegration of the Soviet rear.'

- ^ Mueller, Michael (2007). Canaris. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781591141013. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Carynnyk, Marco (2011). "Foes of our rebirth: Ukrainian nationalist discussions about Jews, 1929–1947". Nationalities Papers. 39 (3): 315–352. doi:10.1080/00905992.2011.570327. Retrieved 27 June 2025.

- ^ Yaniv, Volodymyr (1993). "Melnyk, Andrii". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. 3. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ^ a b Rossoliński-Liebe, Grzegorz (2011). "The "Ukrainian National Revolution" of 1941: Discourse and Practice of a Fascist Movement". Kritika Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 12 (1): 83–114. doi:10.1353/kri.2011.a411661. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ a b Berkhoff K.C., Carynnyk M. (1999). "The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and Its Attitude toward Germans and Jews: Iaroslav Stets'ko's 1941 Zhyttiepys". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 23 (3): 149–184. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ Motyka, Grzegorz (2006). Ukrainian partisans 1942–1960. Activities of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (in Polish). Warsaw: Rytm. ISBN 978-8-3679-2737-6.

- ^ a b Central Intelligence Agency (13 January 1952). "Stepan BANDERA and the ZChOUN (Foreign Section of the Organization of the Ukrainian Nationalists)" (PDF). Declassified Document. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ a b c A. V. Kentii (2004). "Bukovinian Kuren". Encyclopaedia of Modern Ukraine (in Ukrainian).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Radchenko, Yuri (26 April 2023). ""They Fall into Mass Graves… Members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists": Nazi Repressions Against the Melnykites (1941–1944). Part 1". Ukraina Moderna (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Radchenko, Yuri (6 August 2023). ""They Fall into Mass Graves… Members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists": Nazi Repressions Against the Melnykites (1941–1944). Part 3". Ukraina Moderna (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "Stsiborsky, Mykola". Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies; University of Alberta. 1993.

- ^ "Ukrainian National Council (Kyiv)". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. 5. 1993. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Radchenko, Yuri (5 August 2023). ""They Fall into Mass Graves… Members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists": Nazi Repressions Against the Melnykites (1941–1944). Part 2". Ukraina Moderna (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "Kyiv: SD prison (Korolenko street, 33)". Shoah Atlas.

- ^ "Baranovsky, Yaroslav". Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies; University of Alberta. 1984.

- ^ Tyaglyy, Mykhaylo (2024). "A 'Little' Tragedy on the Margins of 'Big Histories': The Romani Genocide in Volhynia, 1941-1944". In Bartash V., Kamusella T., Shapoval V. (ed.). Papusza / Bronisława Wajs. Tears of Blood. Leiden: Brill. pp. 323–363. ISBN 978-3-657-79131-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Sushko, Roman". Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies; University of Alberta. 2013.

- ^ François-Poncet, André (2015). Gayda T. (ed.). Diary of a Prisoner: Memories of a Witness to a Century (in German). Munich: Europa Verlag. p. 158-159. ISBN 978-394-430-585-1. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ "KGB against OUN leader Andriy Melnyk. Documents declassified". Radio Svoboda (in Ukrainian). Radio Liberty. 3 August 2021.

- ^ "Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (Melnykivtsi), OUN(M) [Організація Українських Націоналістів (мельниківців)]". Ukrainians in the United Kingdom Online Encyclopaedia. 2 May 2020.

- ^ a b Myroslav, Yurkevich (1993). "Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists". Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies; University of Alberta.

- ^ a b c Kasianov, Georgiy. "Regarding the ideology of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). Analytical review". WikiReading (in Ukrainian).

- ^ a b "Melnykites". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies; University of Alberta. 2001.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency (11 November 1977). "Major Ukrainian Emigre Political Organizations Worldwide, and in the United States" (PDF). Memorandum for the Record. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ a b c Kasianov, Georgiy (2023). "Nationalist Memory Narratives and the Politics of History in Ukraine since the 1990s" (PDF). Nationalities Papers. 52 (6). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Olena Teliga Publishing House". Encyclopaedia of Modern Ukraine. 2005.

- ^ "Olena Teliha". National Bank of Ukraine. 2025.

- ^ "Oleh Olzhych". National Bank of Ukraine. 2025.

- ^ "Bohdan Chervak becomes First Deputy Head of the State Committee on Television and Radio Broadcasting". Detector Media (in Ukrainian). 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Anxiety over far-right role in Ukraine's plans to mark Babi Yar anniversary". The Jewish Chronicle. 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Memorial complex to Babyn Yar victims: how is the project going?". Ukraine Crisis Media Center. 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Chervak Bohdan Ostapovych". Chesno (in Ukrainian). 2025.

- Draft articles on biographies

- Draft articles on Eastern Europe

- Draft articles on military and warfare

- AfC submissions on history and social sciences

- Pending AfC submissions

- AfC pending submissions by age/3 days ago

- AfC submissions with the same name as existing articles

- AfC submissions by date/04 July 2025