Draft:Literary Commentary in the French Baccalaureate

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 3 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 2,844 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

The literary commentary is one of the two topics offered in the written portion of the preliminary French exam for the baccalaureate in France, along with the essay. This type of exam is also practiced, though with a stronger stylistic focus, in university-level literature programs.

Formerly known as the commentaire composé or commentaire de texte, the literary commentary is, according to the French National Education curriculum, "the space for expressing a personal judgment on a text, using precise and relevant vocabulary that allows for its specific characterization." The purpose is to highlight the literary uniqueness of the passage under study through a rigorous method. Though it is a longstanding exam, it was more formally instituted in 1902.

The literary commentary is specific to exercises proposed in general and technological high school programs since 1972. Graded out of 20 points, it carries a coefficient of 5 in the baccalaureate for both tracks. It is an optional task for the written exam but mandatory for the oral, which takes the form of a line-by-line explanation, regardless of the student's academic track.

To begin, the commentary requires a careful and analytical reading of the excerpt provided. The student must develop a reading approach (that is, a relevant problem or question) that will organize the analysis around two or three main axes. The final piece must be rigorously structured, with an introduction, development, and conclusion.

This exercise draws on analytical and synthetic thinking, critical judgment, and argumentation skills. Always linked to the thematic units of the French program, it rewards a literary culture that is sensitive to grammatical, lexical, versification, or rhetorical techniques the author employs.

Framework

[edit]Since 1969, literary commentary has been one of the three possible topics in the written portion of the preliminary French exam for the baccalaureate in France, alongside the essay and, formerly, creative writing (écriture d'invention). Thus, it is an optional written task but a compulsory part of the oral exam.[1][2] It is defined as "the space for expressing a personal judgment on a text, using precise and relevant vocabulary that allows for its specific characterization."[D 1] The name of the exercise has evolved with changes in curricula and education reforms. It replaced one of the three formats of the "French composition" exam in 1969,[3][2] was first officially titled commentaire de texte in 1972, became commentaire composé in 2002, and has been known as commentaire littéraire since 2006.[4] The term commentaire de texte remains in use in philosophy exams, but the nature of that task differs: it involves analyzing one or more texts without using language-specific tools. In Quebec, a similar exam exists under the name épreuve uniforme de français.[5]

The commentary must be based on a literary text, taken from a work studied in the curriculum (since 2006). However, "the candidate may also be asked to compare two texts."[6] Additionally, since the 2002 reform, the task has always accompanied by a guiding question: "In general tracks, the student writes a structured paper presenting their interpretation and personal judgments. In technological tracks, the prompt is phrased in a way that helps guide the student in their work."[6] The text to be commented on is generally limited to 15–25 lines or one to two pages, especially for theatrical texts.[H 1] After a set of preliminary observation questions, the instruction for the commentary is often very brief: "Write a literary commentary on this text." Today, the practice of literary commentary is often criticized for reducing the text and its literary value. Seen as overly technical, the exercise is said by critics not to allow for a personal or emotional interpretation of the passage.[7]

Finally, "the commentaire composé is commonly practiced from high school through university, as well as in preparatory classes."[I 1] In higher education, especially in literature programs, students are expected to produce "stylistic commentaries."

Educational objectives

[edit]Applying thematic units

[edit]The word text is etymologically a "woven fabric" that brings together various linguistic and stylistic components—components that the commentary must present. The primary goal of the commentary is to assess the student's mastery of all linguistic, stylistic, and literary history tools taught in secondary education. The objective is to apply these thematic units to a literary text to highlight its stylistic value. The student's ability to interpret the text within a specific context is also evaluated. Finally, it contributes to developing writing and oral communication skills (especially for the oral exam), which are part of the "common foundation of knowledge and skills."[I 2]

The commentary involves the explanation of a text that can belong to any genre (theatre, poetry, novel, press article, etc.), any type (argumentative, polemical, epic, narrative, poetic), or any literary period (Romanticism, Surrealism, etc.). The topic must always be tied to a thematic unit in the curriculum. It is a certificative assessment—that is, one that measures the student's ability to understand and reuse the curriculum's thematic tools, such as language tools, clarity of expression, knowledge of literary history, grammar, and terminology used in literary analysis. The official thematic units (as of the 2011 academic year) are:[8]

- In 10th grade (Seconde):[8]

- Comedy and tragedy in the 17th century: Classicism

- Genre and form of argumentation in the 17th and 18th centuries

- The novel and the short story in the 19th century: Realism and Naturalism

- Poetry from the 19th to the 20th century: From Romanticism to Surrealism

- In 11th Grade (Première):[8]

- Theater from the 17th century to the 21st century

- Poetry from the 19th century to the 21st century

- Literature of ideas from the 16th century to the 18th century

- The novel and narrative from the Middle Ages to the 21st century

These fields of study are mandatory. "Their list constitutes one of the essential contributions of the new curricula, which thereby indicate the foundations of the necessary and shared culture of high school students and future citizens."[E 1]

Synthesis and analysis

[edit]The exam also evaluates the student's ability to organize, structure, and explain their text analysis, while identifying the issues it raises. The literary commentary is therefore built on two opposing yet complementary approaches that must be combined in a single production:[9]

- An analytical approach: The student must explain and clarify the text by identifying its conditions and characteristics of production through the collection and study of language devices.[9][10]

- A synthetic approach: The student must also define the main lines of thought based on identified themes or problematics, in other words, the "movements of the text."[G 1]

A linear reading is therefore prohibited; a so-called "juxtalinear" commentary does not highlight what makes the studied text "literary." According to Marcelle Dietrich, "textual explanation through identification" enables the combination of these two approaches, analytical and synthetic, offering an authentic way of reading the text.[J 1]

The guidance document accompanying the curriculum describes the objectives of the literary commentary in the following terms: "The student is thus invited to analyze and understand a text and then to characterize it, to offer a judgment on this text based on the essential characteristics they have identified, and to justify this judgment with an argument founded on the precise analyses they have conducted: the formation of critical judgment and a respectful analysis of the text are the two main objectives."[E 2] The literary commentary is therefore based on a specific method that enables the use of literary devices likely to highlight the author's style, as well as the issues inherent in the text and its context of production. Finally, the student must demonstrate neutrality and objectivity in both their argumentation and writing. According to Jacques Vassevière, commentary remains preferred by French teachers over the essay because of this dual methodological requirement.[11]

An exam that varies by grade level and stream

[edit]"A keystone of French education in high school,"[12] the practice of commentary is acquired only in 11th grade (Première); it is the framework within which students can exercise their critical judgment.[B 1] It should be addressed in every teaching sequence and must allow the reinvestment of language skills acquired.[B 2] In 10th grade (Seconde), it is only introduced through "short and frequent exercises [which] develop creative writing, while also preparing students for commentary writing and the essay."[A 1]

However, the exam differs depending on the educational track. For technological streams: "The wording of the commentary takes the form of two (or even three) questions that guide and map out a 'reading path.'"[H 2] Unlike the literary commentary required in general education tracks, "It is not necessary to require the candidate to write standard transitions, an introduction, and a conclusion," even if logical coherence is still expected. In general education streams, "the commentary may take various forms of organization: a plan in two or three parts, or a more flexible elaboration of a movement that follows the construction of meaning." The final year of the literary track (Terminale littéraire) is the only one at this level that continues with the production of literary commentaries in a more in-depth manner.[H 2]

Attitudes and skills

[edit]The practice of literary commentary "reveals the dismay students feel toward an exercise perceived as complex, for which progressive learning is often abandoned." Bertrand Daunay explains this by pointing to the lack of textbooks on the market specifically designed to help students. This absence contrasts with the overabundance of exam compendia, especially since the exercise engages various student attitudes and abilities. These include acquiring broad cultural knowledge, improving writing skills, engaging in a reflection that extends beyond the purely academic to consider the role of literature in learning French, and mastering metalanguage to refine writing and analysis (competencies that must all be invested in the exam exercise).[13] However, these are scarcely studied by educational psychology, except for work by Isabelle Delcambre and B. Veck. The exercise also allows students to build expert reading skills, and according to Bertrand Daunay, it helps them "gradually form an image of themselves as readers, and break away from their perception of reading, of reading in school, of academic reading."[14] The knowledge required falls into two categories: the "disciplines of the text" (linguistics, rhetoric, stylistics, semiotics, poetics) and literary history (as well as the humanities or history more broadly), while the skills involved are primarily writing-related.[15]

Competences are activated within this exercise. Far from signaling an inability to analyze the text, paraphrasing—when it involves "the fusion of the commented text into the commentary through the (unmarked) incorporation of textual elements from the source text into the commentary" (what Bertrand Daunay calls "detextuality")— indicates a capacity to understand the text. In this regard, the exercises of commentary and summary belong to the same category, as they both engage in the same activity.[16] Learning how to write a textual commentary ultimately offers students a broader reflection when faced with a text. It allows them to engage with the "literary asset," which, according to Yves Reuter, "is neither the text nor the commentary, but the relationship between the two, itself embedded within a specific field and the institutions connected to it."[17] In this way, the literary text is desacralized through the practice of commentary, and the student can develop a critical distance toward it. Other transferable skills in French are also fostered by the commentary exercise, such as the student's ability to identify a difficulty in handling the text or to recognize genre-specific criteria.[18] According to Isabelle Delcambre, the operation of relating these various forms of knowledge (concepts) and skills is specific to literary commentary.[19]

Evaluation

[edit]Written exam

[edit]The literary commentary is one of the optional written exams, lasting 4 hours and graded out of 20 points, with a coefficient of 5.[6] The evaluation criteria are related not only to mastery of language and argumentation but also to a relevant personal reading, effective composition, and demonstrated sensitivity to the text.[G 2] More specifically, the exam allows for the assessment of the following criteria:[H 1]

- understanding of the essential levels of the text (syntactic and textual);[H 1]

- interpretation based on methodical observation;[H 1]

- use of knowledge related to the object of study to shed light on the text;[H 1]

- coherent organizational principle;[H 1]

- clarity, correctness of expression, and spelling.[H 1]

From 2002 until 2021, the preliminary French exam in writing was based on a corpus of 3 or 4 texts (possibly on a short complete work), sometimes accompanied by an iconographic document.[I 3]

Oral exam

[edit]In the oral portion of the preliminary French exam ("EAF") for all sections, including the literature baccalaureate for the literary track, the literary commentary is a mandatory component. In addition to evaluating reading comprehension and textual analysis, the exam also assesses the student's verbal communication skills. As such, the grading rubric used by teachers is based both on a methodical reading and analysis of the text and on the quality of the subsequent interview.[20] The interview lasts 20 minutes, with a preparation time of 30 minutes. The coefficient is 2 for all general[6] and technological streams (ST2S and STG), but 1 for the STI and STL streams. The presentation and the interview are graded out of 10 and then combined to form a score out of 20.

As in the written exam, the literary commentary in the oral exam consists of a textual analysis,[Note 1] which is chosen either from a reading list or from the groupings of texts studied during the year,[F 2003 1] and which the student has studied in class.[F 2003 2]

Consequently, three possibilities are available to the examiner, who remains the sole decision-maker:[22]

- "to question the student on a text or an excerpt from a text included in one of the text groupings";[22]

- "to question the student on an excerpt—previously analyzed in class—taken from one of the complete works studied in analytical reading";[22]

- "to question the student on an excerpt—not previously analyzed in class—taken from one of the complete works studied in analytical reading."[22]

However, the requirement level is lower than in the written exam, due to the limited time and the second part of the test, which consists of a semi-structured interview. In general, the proposed text does not exceed 15 to 20 lines, though it may be longer in the case of a theatrical excerpt. The oral is organized around a question posed by the examiner, which allows the student to structure their reading focus.[F 2003 3] There can be no textual analysis based on extensive reading texts (supplementary texts used during the interview), and in the case of a complete work, any excerpt may be proposed. It is essential that the student take into account the question asked and propose lines of interpretation accordingly. The grading rubric includes assessment of the candidate's skills in expression and communication, their reasoning and analytical abilities, and finally, their knowledge. These three areas are assessed twice: once during the textual presentation, and once during the interview.[6][F 2003 4] Lastly, special accommodations exist for repeating students or those coming from non-contracted institutions.[F 2003 5]

Origin and evolution

[edit]Origin of the exercise: rhetoric and scholasticism

[edit]

The exercise of literary commentary appeared with the educational reform of 1880; since then, it has experienced increasing development to become one of the three major written components of the French baccalaureate.[23]

However, there are similar and older forms of examination. According to Bertrand Daunay and Bernard Veck, "in its scholastic form, commentary is the result of a very ancient lineage that can be traced back to the Hellenistic period, when Homer was commented on both in schools and scholarly circles, notably Stoic ones."[2] The preparatory exercises of Greek rhetoric (progymnasmata) and Roman rhetoric (declamationes), which evaluate students' analytical and synthetic abilities, are forerunners of the literary commentary exercise. Since the Middle Ages, the core of education was rhetoric, with students expected to produce a text by imitating a Latin or Greek author, rarely a French one, however. The quaestiones technique restricted the analysis to a short excerpt or a single proposition.[24]

Nevertheless, critical and analytical study was non-existent until the 19th century. A Jewish tradition—that of biblical commentaries—must also be considered. According to Bertrand Daunay and Bernard Veck, the encounter between these two exegetical traditions took place in Alexandria and gave rise to medieval scholasticism, often considered as focusing on the works of Aristotle, following Thomas Aquinas, as objects of commentary.[2]

Humanism later laid the foundation for the modern philological commentary, notably with Marc Antoine Muret's Commentary on Ronsard's Amours (1553), which is thus one of the first commentaries in France on a secular literary work,[2] and which breaks with earlier forms of exegesis.[25]

Inauguration in 1884

[edit]The written examinations of the baccalauréat were inaugurated in 1830 and officially adopted through the circular issued by Victor Cousin, addressed to rectors on May 8, 1840. This circular recommended the inclusion, in the oral explanation test, of "a certain number of texts from French classics, in prose and verse, which could be analyzed from a literary and even grammatical perspective (...)"[4] With this circular, the rhetoric class ceased to be fundamental and was effectively abolished in 1902. The 1854 reform definitively confirmed the explanation of French authors, as the Ministry of Public Instruction realized that students had poor comprehension of classical texts. From then on, teachers were required to explain French texts to avoid misinterpretations, which involved careful reading and clarification of the stylistic and grammatical devices used.[4] Through this test, the two traditions—oral text explanation and written commentary (stemming from medieval scholasticism)—were united.[2]

The oral exercise appeared in 1874.[26] The turning point in French education came in the 1880s when, as Michel Leroy notes, "the Republic founded the school on patriotic sentiment" through the 1880 educational reform. He adds: "The Latin discourse, the canonical exercise prepared for by the classes of grammar, humanities, poetry, and rhetoric, in a progression legitimized by long tradition, was replaced by French composition and the explanation of French texts."[4] Lists of classical authors have thus been established and maintained to this day.[Note 2]

Creation and specification of the test (1884–1969)

[edit]

In the 19th century, the text commentary test competed with the literary composition exercise. Announced by Charles Thurot in his teaching at the École Normale in the 1870s, by the manuals of Augustin Gazier (in 1880) and Gustave Allais (in 1884), then by the campaigns of Ferdinand Brunot and Gustave Lanson (Études pratiques de composition française, 1898),[27] text commentary was explicitly proposed by literary critic Ferdinand Brunetière in 1899 as an exercise allowing students to acquire knowledge of literary history and genres. In 1910, Dubrulle published a didactic work on what was then called "text explanation," a test that continued in its classical form until 1972.[28] Dubrulle already proposed a precise method for analyzing texts, beginning with reading the text aloud, followed by its historical and social contextualization, and concluding with a technical explanation.[29] Gustave Lanson, for his part, was the first to see text commentary as an exercise in metatextual discourse. The school examination was based on this new epistemological approach introduced by Lanson.[2]

The second turning point occurred with the 1902 reform. With the modernization of author programs, a new discipline emerged: "French text explanation," which "became, from 1902, the main exercise in all classes,"[30] alongside composition, which became the "French dissertation." The text explanation focuses on the writer's style and his treatment of themes, with less emphasis on language tools.

The text commentary, which must be "composed," replaced one of the three forms of the "French composition" test in 1969.[3] It was in this year that the baccalaureate exercises were gradually restricted to three subjects. Before this, the commentary was part of the "first subject," a double exercise that included a summary or analysis/discussion and a text commentary. Two other subjects were also possible in the baccalaureate: "a dissertation on a literary theme" and "a dissertation on an intellectual or moral theme." Within this new definition of the test-exercise, the literary commentary became a "metatextual activity."[31] According to Bertrand Daunay and Bernard Veck, from 1970 onward, the test definitively combined the old requirements of oral explanation and written commentary: "the importance of accounting for a text in its progression," on one hand, and the rigor of construction designed to "methodically reveal the elements of interest that the candidate uncovers in the proposed page," on the other.[2]

In current education (from 1972)

[edit]The literary commentary has been present in the baccalaureate in its current form and framework only since 1972. Initially, two texts are proposed for comparison,[E 3] followed by a composed commentary of a single excerpt. The analysis must take into account language tools as well as stylistic devices. The commentary has, from the beginning, faced competition from the dissertation exercise: "The text commentary, accompanied by instructions outlining the method to follow, would not truly be proposed until 1902. The dissertation surpasses descriptions and narratives, speeches, and commentaries. Literary subjects gradually eclipse historical and moral subjects."[32] The commentary exercise thus reflects the evolution of French teaching, which can be seen as: "The evolution from a pedagogy of imitation to a pedagogy of commentary,"[32] according to Michel Leroy. However, it was "as early as 1970 that the commentary was separated from the summary, with no specific explanation for this split." This led to a "generic rigidity," according to Bertrand Daunay. The term "composed commentary" first appeared in the 1983 circular. The same year, a service note clarified the principles of the written baccalaureate exams and defined the specificity of each exercise.[33] The introduction of methodical reading in the 1987 curriculum reinforced the literary and interpretative specificity of the test. The most recent curricula reaffirm this, but now refer to it as analytical reading.[2]

According to Bertrand Daunay, "a clear dichotomy is marked between creative writing and metatextual writing," which refers to the literary commentary. This dichotomy includes the double opposition between rhetorical culture and commentary culture, as well as between metatextual writing and hypertextual writing. The commentary, in my own words from the 2001 Curriculum Guide, is an exercise that belongs "to the domain of critical discourse on literature."[34] The commentary exercise suffers from the competition of creative writing, a less regulated and more free activity, and although these two exercises are close to one another in terms of the mobilization of knowledge and skills,[35] there exists a "continuum between creative writing and metatextual writing."[36]

Furthermore, the exercise encompasses several activities and formal variations. According to Bertrand Daunay, one can speak of a genre because "it is the prescriptions (and not the realizations) that gradually construct the genre" of the literary commentary, no longer as a simple school exercise, but as a unique production. Reflecting on the history of the literary commentary in French and literature education, Bertrand Daunay notes that two things have changed in its definition. First, linguistic, textual, or discursive characteristics are not always identified by official texts. Secondly, cognitive characteristics are the ones that have evolved the most between the various explanations of the exercise. This evolution must be compared with that of the reading practice within the French educational system, which has also been reshaped since 1969.[37]

Literary techniques to reintegrate into the exercise

[edit]

Mastering literary analysis

[edit]The axes of the commentary are based on theses or ideas determined by its reading. These ideas rely on arguments referring to literary and writing techniques specific to the text to be commented on and studied in class. At this level, being a literary analysis, it is important to use the appropriate vocabulary[G 3] and terminology, employing a range of synonyms and using precise adjectives, particularly by resorting to the lexicon of feelings and that of abstraction.[D 2] For instance, knowing the names of stylistic figures is essential, with any correction partially based on knowledge of both the name and function of the techniques covered in the curriculum. Manipulating various techniques (grammatical, lexical, stylistic, linguistic, etc.) and the need to establish and identify relationships between textual phenomena at different linguistic levels constitute the didactic difficulty of the literary commentary exercise.[2]

A literary commentary thus uses "analysis tools" that must be reintegrated depending on the specificity of the text to be analyzed and the educational track followed.[H 3] The use of a precise method, for example, based on categorization through tables or the use of colors, helps improve text analysis.[J 2]

Lexical elements

[edit]The study of a text is based on a set of linguistic tools capable of bringing out its style and originality. The study of lexical fields and semantic fields is fundamental to highlight the themes of the passage, notably through literary isotopies. The play on polysemy or paronymy also allows for semantic perspectives. Studying adjectives (both evaluative and pejorative) and those reflecting the enunciative framework (particularly axiological adjectives) is crucial.[G 4]

Etymology should also be identified, although this aspect requires a deep knowledge of the evolution of the language, which Latin scholars are often the only ones capable of applying. The study of enunciation is increasingly required in curricula.[I 4] It concerns how the author presents themselves within their text and makes it an object of communication. The study of discourse and speech acts (reported speech, free indirect discourse, indirect speech, and direct discourse) is crucial in the case of a narrative alternating between dialogue and narration. Finally, the study of the registers and literary tonalities of the language used in the text (comedic, lyrical, epic, fantastic, etc.) connects the text to a genre and a literary movement covered in the curriculum.[G 5]

Syntactic and stylistic elements

[edit]Draft identification has helped highlight the subjects of sentences, the interplay of complements (direct object, indirect object, object of the preposition), and the nature of the verbs used by the author (action verbs, movement verbs, perception verbs, state verbs, attributive verbs). Coordinators must be identified (conjunctions of coordination, conjunctions of subordination, or conjunctive phrases) because they reveal the logical progression of the text, especially in the case of an argumentative excerpt.[I 5]

The author employs formal techniques that define their style and highlight their ideas and themes. Stylistic and rhetorical figures help determine the effects the author aims to produce on the reader.[I 6] The study of focalization viewpoints shows how the author (or narrator) involves and energizes their text. The study of argumentation, a key focus in the curriculum, should be done by shedding light on the literary registers and the external context of production.[G 6]

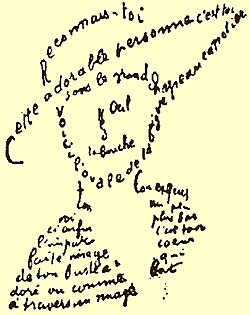

Rhythmic and prosodic elements

[edit]Although most prevalent in the poetry analysis, rhythmic and prosodic techniques also exist in prose texts. Identifying these elements helps clarify the internal dynamics of the passage, its strength, and its originality as a literary and cultural object. The versification must be precise: counting syllables and vers, considering hiatuses, caesurae, hemistichs, enjambments, and other elements are essential to link the excerpt to a specific genre or literary movement.[I 7]

The study of stylistic figures specific to poetic rhythm, such as alliteration and assonance, is part of the curriculum. The study of punctuation and typography (paragraphs, poetic stanzas) is also included. The study of versification, specific to poems, primarily focuses on identifying the type of poem (sonnet, rondeau, ballad, etc.) and the meter type (alexandrine, octosyllabic, etc.). The study of rhymes (alternating, crossed, or flat) and, if applicable, the graphic design for image poems (e.g., calligrams) should also be completed. The study of prosody allows one to account for the unique rhythm of the text (concepts of period and cadence).[I 8]

Issues

[edit]

The commentary must highlight the understanding of the specific issues of the text being studied. Defining the issues—or "reading axes"—helps determine the type of structure.[38] However, simply following the text is not enough: one must also draw upon their own general knowledge to enrich the study, demonstrate argumentative skills, and reintegrate the objects of study from the curriculum.[39]

Exploration of the text and reading/writing strategies

[edit]The literary commentary has a dual didactic contract: it is an exercise that involves both writing and reading. Regarding the writing of literary commentaries in high school, Dominique Bucheton identifies four writing approaches, which he calls "commentary behaviors": "the impossible takeoff," "exploring like a maverick," "the diligent student," and "maximum distance and integration."[K 1] Since the commentary exercise is inherently metatextual, writing and reading strategies are closely interconnected. The learning challenge, in this case, is for the student to acquire a "scriptural image," a concept that "refers to the close relationship between the two activities, and the great difficulty, sometimes, especially in the analysis of metatextual writings such as commentaries, of determining whether what is being analyzed belongs to the realm of writing or the staging of reading practices and relationships to the read text."[K 2] This scriptural image encompasses the text reception and the student's cultural knowledge.

Understanding the text, through careful and analytical reading, "based on the rigor and rationality of positive observation," is central to the exercise. Within the discipline of teaching literature, the literary commentary constitutes a "unique mode of grasping and appropriating the text, through selections (quotations) subjected to reasoned study, the goal of which is ultimately to provide a "literary" reading of the text."[2]

Argumentation and development of critical thinking

[edit]The "study of argumentation and its effects on recipients" lies at the heart of the literature curriculum, alongside the development of critical judgment.[E 4] The circular outlining the 2006 curriculum adds that mastering the main forms of argumentation (especially deliberation) is specifically the focus for the classes of Première and Terminale, across all series.[C 1][E 5]

However, the commentary should not simply be a catalog of knowledge acquired in class. The student must also argue and demonstrate sensitivity to the text and, more generally, to literature and the arts. The official bulletin of November 2, 2006 (No. 40) explains the importance of this critical dimension:[C 2]

The development of autonomous critical thinking, at the end of the mandatory common French education, students should be able to read, understand, and comment on a text by themselves, identifying language, history, context, argumentation, and aesthetic issues that may be relevant to its subject; they should be able, based on their readings, to formulate a well-argued personal judgment, particularly in a commentary or dissertation.[C 2]

In this sense, the literary commentary, according to Élisabeth Bautier and Jean-Yves Rochex, is a "personal space for thought and analysis," a "construction of an experience of the world and language" for Bertrand Daunay.[31]

Importance of general knowledge

[edit]A literary commentary cannot be written without acquiring a minimal level of general and literary culture; it must, within the limits of the text, serve as an opportunity to present one's knowledge in order to enrich the study through understanding the context of its writing, knowledge of the author's biography, and by drawing parallels with historical and social events.[40]

In itself, the literary commentary, like the dissertation, is an exercise where the cross-disciplinarity of knowledge and its relationship to other subjects is paramount, an objective of the National Education system to break down subject silos. The Bulletin officiel No. 40 of 2006 specifies these transdisciplinary expectations:[C 3]

As a crossroads discipline, French develops skills essential in all subjects. More specific connections will be made (and indicated as such to students) with the following disciplines:

- The arts, particularly for the study of genres and registers, cultural history, and image analysis.[C 3]

- Classical languages, for the study of genres and registers, literary and cultural history, and lexicon;[C 3]

- Modern languages, especially in the approach to European cultural movements;[C 3]

- History, including the history of science, for constructing cultural history issues.[C 3]

- Philosophy, which students will study in their final year, through reflection on registers, cultural history, and language, and through the training of commentary writing and dissertation skills.[C 3]

Regulatory texts related to literary commentary

[edit]- Bulletin Officiel (November 7, 2002). "Programme d'enseignement du français en classe de seconde des séries générales et technologiques" [French language teaching program for second-year students in general and technical streams]. Bulletin Officiel (in French) (41). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Bulletin Officiel 2002, Section III - Mise en œuvre

- Bulletin Officiel (July 12, 2001). "Programme d'enseignement du français en classe de première des séries générales et technologiques" [French language teaching program for first-year students in general and technical streams]. Bulletin Officiel (in French) (28). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Bulletin Officiel 2001, Section I - Objectifs

- ^ Bulletin Officiel 2001, Section VI4. - L'étude de la langue

- Bulletin Officiel (November 2, 2006). "Modification du programme applicable à la rentrée 2007" [Change to the program applicable at the start of the 2007 academic year]. Bulletin Officiel (in French) (40). Archived from the original on February 28, 2008.

- ^ Bulletin Officiel 2006, II - Content

- ^ a b Bulletin Officiel 2006, Chapter I - Objectives

- ^ a b c d e f Bulletin Officiel 2006, Section V - Relations avec les autres disciplines

- French Ministry of National Education; School Education Department (2002). Littérature, classe terminale de la série littéraire [Literature, final year of the literary series] (PDF) (in French). National Center for Educational Documentation. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2005.

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2002, p. 50: The circular continues: "identification of genre, register, literary movement, topos, its significance, and its place in an intertextual network. Acquiring and mastering this specific vocabulary, which promotes 'accuracy of expression,' are major objectives of the final year of literary studies. The accurate characterization of a text and the rigorous formulation of its specificity are essential skills to be developed in literary education."

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2002, p. 40

- French Ministry of National Education; School Education Department (2007). Littérature, classe terminale de la série littéraire [Literature, final year of the literary series] (PDF) (in French). National Center for Educational Documentation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2009.

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2007, p. 33

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2007, p. 91

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2007, p. 85

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2007, p. 8

- ^ French Ministry of National Education & School Education Department 2007, p. 9: "The elements of argumentation were covered in middle school; in high school, they are examined in a more analytical way. The tenth grade class focuses mainly on ways to convince and persuade. In eleventh grade, the emphasis is on the forms and practices related to deliberation."

- Bulletin Officiel (January 16, 2013). "Modalités de l'oral à compter de la session 2003" [Oral exam procedures starting with the 2003 session]. Bulletin Officiel (in French) (3). Archived from the original on January 18, 2009.

- ^ "The excerpt is taken from one of the groups of texts or one of the complete works studied in analytical reading listed in the reading and activity description."

- ^ The candidate must ensure that they bring the documents studied during the year: "For the exam, the candidate must bring: 1. their copy of the reading and activity description; 2. two copies of the textbook used in their class; 3. a set of photocopies of texts not included in the textbook, identical to the one sent to the examiner; 4. two copies of the complete works studied."

- ^ Section II - Definition.

- ^ Section III - Assessment of the oral exam.

- ^ Section Special cases.

- French Ministry of National Education; School Education Department (2002b). Nouvelle épreuve anticipée de français. Annales zéro : commentaires et éléments de corrigé. Texte de présentation [New anticipated French exam. Past papers: comments and answer key. Presentation text] (PDF) (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2010.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "The assimilation of commentary and text explanation has not historically been a given," notes Bertrand Daunay. Confused in old curricula, these two exercises have different purposes. "Text explanation was born from the desire to give legitimacy to the corpus of French literary texts that were not subject to serious analysis, unlike Greek or Latin texts... The model invoked is the explanation of ancient authors, and explanation is conceived primarily as a translation," continues Bertrand Daunay.[21]

- ^ Michel Leroy reminds us of the thirteen authors selected for the baccalaureate examination:

Pierre Corneille (Le Cid, Polyeucte),

Jean Racine (Britannicus, Esther, Athalie),

Molière (The Misanthrope),

Jean de La Fontaine, with the Fables and Philemon and Baucis,

Nicolas Boileau (Les Épîtres and L'Art poétique),

Blaise Pascal (The first two letters of the Provinciales),

Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (The Funeral Oration for the Queen of England and the Prince of Condé; the third part of Discourse on Universal History),

Fénelon (Dialogues on Eloquence, and some excerpts from Les Aventures de Télémaque),

Jean de La Bruyère ("Des ouvrages de l'esprit," in Les Caractères),

Jean-Baptiste Massillon (Le Petit Carême),

Montesquieu (Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline),

Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (Discours sur le style),

Voltaire (The Age of Louis XIV).[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Épreuve écrite de français (définition applicable à compter de la session 2008 des épreuves anticipées des baccalauréats général et technologique)" [Written French exam (definition applicable as of the 2008 session of the early general and technological baccalaureate exams)]. B.O (in French). December 14, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2025.: (...) the subject offers a choice between three types of writing tasks, related to all or part of the texts studied: a commentary, an essay, or creative writing. This written work is marked out of a minimum of 16 points for general subjects and 14 points for technological subjects when preceded by questions, and out of 20 in all subjects when there are no questions.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Daunay & Veck 2005

- ^ a b Daunay 2005, p. 49

- ^ a b c d e Leroy, Michel (2002). "La littérature française dans les instructions officielles au XIXe siècle" [French literature in official instructions in the 19th century]. Revue d'histoire littéraire de la France (in French). Revue d'histoire littéraire de la France (3): 365–387. doi:10.3917/rhlf.023.0365. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ "Épreuves uniformes de français" [Standardized French tests]. Department of Education, Recreation, and Sport (in French). Archived from the original on February 12, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Modalités de l'oral à compter de la session 2002" [Oral exam procedures starting with the 2002 session]. B. O. (in French) (26). June 28, 2001. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Ceysson, Pierre (2006). "La poésie contemporaine" [Contemporary poetry]. Lidil (in French). 33. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Épreuves anticipées de Français, exemples de sujets (2002)" [Early French exams, sample questions (2002)]. eduscol.education.fr (in French). Archived from the original on January 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Adam, Jean-Michel (2005). Analyse de La linguistique textuelle - Introduction à l'analyse textuelle des discours [Analysis of Textual Linguistics: Introduction to Textual Analysis of Discourse] (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2-200-26752-5.

- ^ "Méthodologie de la dissertation littéraire (composition française)" [Methodology of literary essay writing (French composition)] (PDF) (in French). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Vassevière, Jacques (2001). "Nouvelles questions sur le français au baccalauréat" [New questions on French in the baccalaureate]. L'École des lettres (in French) (3): 77–80. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Delcambre 1989, p. 1

- ^ Daunay 1993, p. 1

- ^ Daunay 1993, p. 27

- ^ Delcambre 1989, p. 2

- ^ Daunay 1993, pp. 55–56

- ^ Daunay 1993, p. 22

- ^ Daunay 1993, p. 26

- ^ Delcambre 1989, p. 16

- ^ "Exemple d'une grille d'entretien élaboré pour l'oral du commentaire composé" [Example of a maintenance grid developed for the oral component of the written commentary]. lettres.net (in French). Archived from the original on April 2, 2016.

- ^ Daunay 1993, p. 56

- ^ a b c d "Programmes et ressources en français - voie GT" [Programs and resources in French - GT track]. Éduscol (in French). 2025. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Chartier, R (1996). Les pratiques de l'écrit [Writing practices] (in French). Paris: Fayard.

- ^ Léon, Antoine; Roche, Pierre (2005). Histoire de l'enseignement en France [History of education in France]. Que sais-je ? (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. p. 26. ISBN 2-13-055221-8.

- ^ Muret, Marc-Antoine; de Ronsard, Pierre; Chomarat, Jacques; Fragonard, Marie-Madeleine; Mathieu-Castellani, Gisèle (1985). Commentaires au premier livre des Amours de Ronsard [Comments on the first book of Ronsard's Amours] (in French). Vol. 1: Travaux d'humanisme et Renaissance. Librairie Droz. pp. XXVII–LXIV. ISBN 978-2-600-03118-9. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Léon, Antoine; Roche, Pierre (2005). Histoire de l'enseignement en France [History of education in France]. Que sais-je ? (in French). Paris: PUF. p. 85. ISBN 2-13-055221-8.

- ^ Chervel, André (2002). "Le baccalauréat et les débuts de la dissertation littéraire (1874–1881)" [The baccalaureate and the beginnings of literary essays (1874–1881)]. Histoire de l'éducation (in French) (94): 103–139. doi:10.4000/histoire-education.816. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Dubrulle, A (1910). Explication des textes français : principes et applications [Explanation of French texts: principles and applications] (in French). Belin.

- ^ Jey, Martine (1998). "La littérature au lycée: invention d'une discipline (1880–1925)" [Literature in high school: the invention of a subject (1880–1925)]. Recherches Textuelles (in French). 3. Université de Metz: 89. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Chervel, André (2002). "Le baccalauréat et les débuts de la dissertation littéraire (1874–1881)" [The baccalaureate and the beginnings of literary essays (1874–1881)]. Histoire de l'éducation (in French) (94): 103–139. doi:10.4000/histoire-education.816. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Daunay 2005, p. 51

- ^ a b Leroy, Michel (2000). Historique des épreuves du baccalauréat [History of the baccalaureate exams] (in French). Eduscol.

- ^ Daunay 2005, p. 52

- ^ Daunay 2003, p. 31

- ^ Daunay 2003, p. 36

- ^ Daunay 2003, p. 37

- ^ Daunay 2005, p. 50

- ^ "Le commentaire d'un texte littéraire (dossier complet)" [Commentary on a literary text (complete file)] (PDF). Lettres.net (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 8, 2007.

- ^ "Commentaire littéraire (baccalauréat) - Définition" [Literary commentary (high school diploma) - Definition]. Techno-Science (in French). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ "La méthode du commentaire au bac de francais" [The commentary method in French baccalaureate exams]. Commentaire Composé (in French). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- Reithmann, Annie; Bricka, Blandine (2004). Réussir le commentaire composé [Writing a successful commentary essay]. Principes (in French). Vol. 522. Studyrama. ISBN 978-2-84472-382-6.

- ^ Reithmann & Bricka 2004, p. 20

- ^ Reithmann & Bricka 2004, p. 13

- ^ Reithmann & Bricka 2004, p. 53

- ^ Reithmann & Bricka 2004, pp. 22–23

- ^ Reithmann & Bricka 2004, pp. 17–18

- ^ Reithmann & Bricka 2004, pp. 26–30

- Fourcault, Laurent (2005). Le commentaire composé [The composite commentary]. Collection 128 (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2-200-34080-X.

- ^ Fourcault 2005, p. 5

- ^ Fourcault 2005, p. 8

- ^ Fourcault 2005, p. 34

- ^ Fourcault 2005, pp. 16–17

- ^ Fourcault 2005, p. 15

- ^ Fourcault 2005, p. 18

- ^ Fourcault 2005, pp. 22–23

- ^ Fourcault 2005, p. 24

- Dietrich, Marcelle (1998). "Le commentaire littéraire" [Literary commentary]. Québec français (in French) (109): 37–40. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Dietrich 1998, p. 37

- ^ Dietrich 1998, p. 38

- Delcambre, Isabelle (2007). "Du sujet scripteur au sujet didactique" [From writing subject to teaching subject]. Le Français aujourd'hui (in French) (157): 33–41. doi:10.3917/lfa.157.0033. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Delcambre 2007, p. 7

- ^ Delcambre 2007, pp. 20–21

Bibliography

[edit]Methods

[edit]- Anglard, Véronique (2006). Le commentaire composé [The composite commentary]. collection Cursus (in French). Armand Colin. ISBN 2-200-34668-9.

- Preiss, Axel; Aubrit, Jean-Pierre (1995). L'explication Littéraire et le commentaire composé [Literary explanation and commentary]. Cursus Littérature (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2-200-26140-3.

- Geyssant, Aline; Lasfargue-Galvez, Isabelle; Raucy, Catherine (2002). Le commentaire en français [The commentary in French]. Profil littérature (in French). Hatier. ISBN 978-2-218-73938-5.

- Bilon, Marcelle; Marguliew, Henri (1998). Épreuve de français premières, commentaire littéraire ou étude littéraire [French exam for first-year high school students, literary commentary or literary analysis] (in French). Ellipses. ISBN 978-2-7298-9671-3.

- Costa, Denise; Moulonguet, Francis (1998). Méthode littéraire : de la découverte d'un texte au commentaire composé [Literary method: from discovering a text to writing a commentary] (in French). SEDES. ISBN 978-2-7181-9098-3.

- Marguliew, Henri (1996). Commentaire littéraire ou étude littéraire : épreuves anticipées de français : deuxième sujet [Literary commentary or literary analysis: French mock exams: second topic] (in French). Paris: Ellipses. ISBN 2-7298-9671-6.

- Preiss, Axel (1994). L'explication littéraire et le commentaire composé [Literary explanation and commentary] (in French). Armand Colin. ISBN 978-9973-19-375-9.

Didactic and socio-educational studies

[edit]- Boucris, Luc; Elzière, Catherine (1994). Lectures croisées. Le commentaire de textes en français, histoire, philosophie [Cross-reading. Commentary on French texts, history, philosophy] (in French). Paris: Adapt (Association for the Development of Teaching Aids and Technologies) SNES and René Pélissie. ISBN 2-909680-11-8.

- Bucheton, Dominique (1996). "Diversité des conduites d'écriture, diversité du rapport au savoir : Un exemple : le commentaire composé en seconde" [Diversity of writing styles, diversity of approaches to knowledge: An example: the essay written in 10th grade]. Le Français aujourd'hui (in French) (115): 31–41.

- Collectif (2000). Le commentaire littéraire dans la classe de français : effet d'une réforme sur les pratiques [Literary commentary in French class: the effect of reform on teaching practices] (in French). Paris/Nantes: National Institute for Educational Research: IUFM (University Institute for Teacher Training) of the Pays-de-la-Loire region. ISBN 2-7342-0680-3.

- Daunay, Bertrand; Veck, Bernard (2005). "Commentaire littéraire" [Literary commentary]. Dictionnaire encyclopédique de l'éducation et de la formation [Encyclopedic dictionary of education and training]. Les usuels (in French). Retz. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-2-7256-2424-2.

- Daunay, Bertrand (1993). "De l'écriture palimpseste à la lecture critique. Le commentaire de texte du collège au lycée" [From palimpsest writing to critical reading. Text commentary from middle school to high school] (PDF). Recherches (in French) (18): 93–130. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- Daunay, Bertrand (2002). "Le lecteur distant : Positions du scripteur dans l'écriture du commentaire" [The remote reader: Positions of the writer in writing commentary]. Pratiques (in French). 113 (113/114): 135–153. doi:10.3406/prati.2002.1951. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010.

- Daunay, Bertrand (2003). "Les liens entre écriture d'invention et écriture métatextuelle dans l'histoire de la discipline : quelques interrogations" [The links between creative writing and metatextual writing in the history of the discipline: some questions] (PDF). Enjeux (in French) (57): 9–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2011.

- Daunay, Bertrand (2005). "Le commentaire : exercice, genre, activité ?" [Commentary: exercise, genre, activity?] (PDF). Cahiers Théodile (in French) (5): 49–61. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2014.

- Delcambre, Isabelle (1989). "L'apprentissage du commentaire composé : comment innover ?" [Learning to write commentary: how can we innovate?]. Pratiques (in French). 63 (63): 13–36. doi:10.3406/prati.1989.1513.

- Veck, Bernard (1988). Production de sens, Lire/écrire en classe de seconde [Meaning production, Reading/writing in 10th grade]. Rapports de Recherches (in French). INRP. ISBN 2-7342-0200-X. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

External links

[edit]Official rules

[edit]- "Eduscol : site pédagogique de l'Éducation nationale (programmes et compléments)" [Eduscol: educational website of the French Ministry of Education (curricula and additional resources)] (in French). Archived from the original on February 2, 2007.

- "Définition des épreuves de Français, écrit et oral, document officiel" [Definition of French written and oral exams, official document] (in French). Archived from the original on January 16, 2007.

- "Grille d'évaluation du plan détaillé" [Detailed plan evaluation grid] (in French). Archived from the original on May 19, 2003.

Literary commentary method

[edit]- "Méthode du commentaire littéraire" [Literary commentary method]. Magister (in French). Archived from the original on February 10, 2003.

- "Méthode du commentaire composé" [Composed commentary method] (in French). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- "Fiches de méthode" [Method sheets]. Études Littéraires (in French). Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- "Rédiger un commentaire composé" [Write a detailed comment]. Espace Francais (in French). 8 July 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- "Fiche méthodologique" [Methodology sheet] (in French). Archived from the original on December 13, 2007.

- "Le commentaire composé: questions et méthode" [The essay: questions and method] (in French). Archived from the original on January 6, 2007.

- "Les étapes du commentaire littéraire avec des exemples" [The stages of literary commentary with examples] (in French). Archived from the original on January 5, 2007.

- Hébert, Luis (2011). "Méthodologie de l'analyse littéraire" [Methodology of literary analysis] (PDF). Signo (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 9, 2011.

Annals of topics and examples of annotated texts

[edit]- "French Baccalaureate Exam Archives" (in French). Archived from the original on July 2, 2011.

- Gachon. "Example of a commentary composed of a poem from the poem "Elle était déchaussée, elle était décoiffée..." by Victor Hugo" (in French). Archived from the original on June 11, 2012.

- "Example of a commentary composed of an excerpt from René by Chateaubriand" (in French). Archived from the original on February 22, 2008.

- Nascimento, Flávia (2006). "Commentaire composé sur "Lisbonne. Livre de bord. Voix, regards, essouvenances", de José Cardoso Pires" [Comprehensive commentary on "Lisbon. Logbook. Voices, Glances, Memories" by José Cardoso Pires] (PDF) (in French). Retrieved May 2, 2025.