Draft:Influence of severe weather during 2021 on American politics

During 2021, several severe weather disasters, including tornadoes, hurricanes, winter storms, and wildfires, affected American federal, state, and local politics, leading to various state of emergency declarations, investigations, controversies and new legislation.

Fultondale tornado

[edit]

In the late evening hours of January 25, 2021, a large and intense tornado hit the cities of Fultondale and Center Point, both located north of Birmingham, Alabama. The tornado, which was on the ground for 10 miles (16 km), inflicted extensive damage to homes and businesses, reaching a maximum intensity of EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita scale. The tornado damaged 265 homes and killed one person who was sheltering in a basement.[1][2] The COVID-19 pandemic in Alabama, which was affecting Alabama at the time of the tornado, made the Jefferson County Emergency Management Agency change how their emergency activation centers are usually operated following the disaster.[3][4]

February winter storms

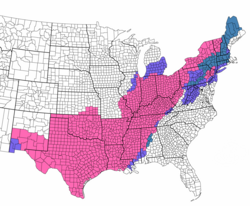

[edit]During February 2021, the United States was affected by four back-to-back historic ice and winter storms along with a major cold wave, with the state of Texas receiving the worst impacts. The storms triggered the worst energy infrastructure failure in Texas state history, leading to shortages of water, food, and heat.[5] The winter storms led to extreme political controversy, as well as numerous investigations.

| |||||

| Winter Storm Warning | |||||

| Winter Storm Watch | |||||

| Winter Weather Advisory | |||||

On February 10, an ice storm began impacting states in the Ohio Valley region as well as the Upland South.[6] On the early morning of February 11, due to the frigid weather, Interstate 35W in Fort Worth, Texas was icy, which was unusual for the area. As a result, at 6:30 AM CST the first collision occurred when a vehicle skidded off the road, which led to several vehicles, including semi-trucks, to pile up on the freeway. Ultimately, 133 cars piled in the incident which left motorists trapped in their vehicles. Six people died and sixty-five people were transported to a local hospital.[7] The National Transportation Safety Board performed a safety investigation of the crash, and released a report on January 18, 2023.[8] The storm is estimated to have caused over $75 million (2021 USD) in damages.[9] From February 11–12, the next storm brought light to moderate snow to the Rocky Mountains. Then, energy from that storm later caused a significant icing event in the Mid-Atlantic and Appalachians. From Kentucky to North Carolina, 480,000 customers were left without power. The first ever ice storm warning was issued for the Greater Richmond Region as well.[10] The 6.1 in (15 cm) of snowfall in Portland, Oregon on February 12 ties the airport monthly record of 6.1 in (15 cm) set Feb 19, 1993.[11] The event proved to be historic for the Portland metropolitan area in the month of February. Some areas in Oregon saw up to 1.5 in (38 mm) of ice accretion.[12]

| |||||

| Winter Storm Warning | |||||

| Winter Storm Watch | |||||

| Winter Weather Advisory | |||||

A third, unusually significant winter storm impacted the Pacific Northwest from February 12 to 13; Seattle received 11.1 inches (28 cm) of snow.[13][14] Texas Governor Greg Abbott announced a federal emergency declaration after a significant snow event in Texas accompanied by extreme cold.[15][16] The storm caused blackouts for nearly 10 million customers in the United States and in northern Mexico, triggering a severe power crisis in Texas in the process.[17][18] The storm killed at least 237 people, including 223 in the United States and 14 in Mexico.[19][20][21][22][23] This storm is estimated to have caused over $25.5 billion (2021 USD) in damages, including at least $24 billion in the United States and over $1.5 billion in Mexico, making it the costliest winter storm recorded in U.S. history and worldwide.[24][25][26]

A fourth storm brought a record-breaking 9 inches (23 cm) of snow to Del Rio, Texas and threatened Little Rock, Arkansas's snowfall record with 11.8 inches (30 cm) falling there. It brought Little Rock's snow cover up to 15 inches (38 cm), breaking the all-time record there. Up to 14 inches (36 cm) fell to the south of the city.[27] Elsewhere in the region, 0.1 inches (2.5 mm) to 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) of ice accretion impacted Houston, 4 inches (10 cm) of snow fell in Oklahoma City and 7.2 inches (18 cm) in Memphis, Tennessee.[28][29] Impacts from the storm stretched all the way into Massachusetts. 100 cars became stranded on roadways near Florence, Alabama due to the wintry weather. Up to 0.5 inches (13 mm) of ice accretion was reported in parts of Virginia, West Virginia and North Carolina. 10.2 inches (26 cm) of snow fell in Norristown, Pennsylvania. The storm brought Philadelphia's total seasonal snowfall total to 22.5 inches (57 cm), which is exactly average.[30] The system killed at least 29 people,[31][32] and it is estimated to have caused at least $2 billion (2021 USD) in damages.[25]

Texas power crisis

[edit]More than 4.5 million homes and businesses were left without power,[33][34][35][36] some for several days. At least 246 people were killed directly or indirectly,[37] with some estimates as high as 702 killed as a result of the crisis.[38]

State officials, including Republican governor Greg Abbott,[39] initially erroneously blamed[40] the outages on frozen wind turbines and solar panels. Data showed that failure to winterize traditional power sources, principally natural gas infrastructure but also to a lesser extent wind turbines, had caused the grid failure,[41][42] with a drop in power production from natural gas more than five times greater than that from wind turbines. Texas's power grid has long been separate from the two major national grids to avoid federal oversight, though it is still connected to the other national grids and Mexico's;[43] the limited number of ties made it difficult for the state to import electricity from other states during the crisis.[44] Deregulation of its electricity market beginning in the 1990s resulted in competition in wholesale electricity prices, but also cost cutting for contingency preparation.[44]

The crisis drew much attention to the state's lack of preparedness for such storms,[45] and to a report from U.S. federal regulators ten years earlier that had warned Texas that its power plants would fail in sufficiently cold conditions.[46][47] Damages due to the cold wave and winter storm were estimated to be at least $195 billion,[24] likely the most expensive disaster in the state's history.[48] According to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the Texas power grid was four minutes and 37 seconds away from complete failure when partial grid shutdowns were implemented.[49][50] During the crisis, some energy firms made billions in profits, while others went bankrupt, due to some firms being able to pass extremely high wholesale prices ($9,000/MWh, typically $50/MWh) on to consumers, while others could not, with this price being allegedly held at the $9,000 cap by ERCOT for two days longer than necessary, creating $16 billion in unnecessary charges.[51][52]

On February 16, 2021, Governor Greg Abbott declared that ERCOT reform is an emergency priority for the state legislature, and there would be an investigation of the power outage to determine long-term solutions.[53] The legislature held hearings with power plant chief executives, but not with natural gas industry leaders.[48] In March 2021, Congress launched an investigation into the power crisis by requesting documents relating to winter weather preparedness from the Texas electric grid manager and ERCOT.[54] The Railroad Commission blamed power producers for gas supply issues, even though its chair Christi Craddick was aware of gas supply problems prior to the outages. Cold weather disrupted 22 gas processing plants two days before blackouts began.[48] The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is investigating anomalies in the natural gas market, where companies may have illegally manipulated prices. Intrastate pipelines are not required to report their tariffs like interstate pipelines, making it harder to investigate. FERC was unable to say if there was price gouging.[48] Texas attorney general Ken Paxton has not announced investigations into energy prices.[48]

On June 14, 2024, the Supreme Court of Texas ruled on a case regarding the incident, holding that the Public Utility Commission of Texas acted within its authority as a state agency in taking emergency measures that raised the price of electricity, and was therefore immune from suit.[55] In an April 2024 ruling by the Fourteenth Court of Appeals in Texas, a three-judge panel in Houston granted defendants known as transmission and distribution utilities (TDUs) dismissals of some causes of action filed by homeowners and other plaintiffs, but ruled that plaintiffs' claims for gross negligence and intentional misconduct could move forward.[56][57] The TDU defendants include CenterPoint Energy, Oncor Electric Delivery, and American Electric Power.[58]

March 2021 Hawaii floods

[edit]Tropical Storm Claudette

[edit]

Tropical Storm Claudette was a weak tropical cyclone that caused heavy rain and tornadoes across the Southeastern United States in June 2021, leading to severe damage. Claudette produced gusty winds, flash flooding, and tornadoes across much of the Southeastern United States. Claudette overall caused minor impacts along the Gulf of Campeche's coastline due to the system stalling in the region as an Invest and a Potential Tropical Cyclone. Impacts were most severe in Alabama and Mississippi, where heavy rains caused flash flooding. Several tornadoes in the states also caused severe damage, including an EF2 tornado that damaged a school and destroyed parts of a mobile home park in East Brewton, Alabama, injuring 20 people. A total of 14 people died in Alabama due to the storm, including 10 from car accidents. Monetary losses across the United States is estimated to be at $375 million.[59]

Heavy rainfall and strong thunderstorms affected much of Alabama, with the greatest precipitation occurring along two bands in the northern and southern portions of the state. The highest measured rainfall total was 6.44 in (164 mm) in northeastern Alabama, though meteorologists at the National Weather Service estimated totals may have been locally higher.[60] Near Tuscaloosa, a private dam failed and the subsequent flooding washed out a water and sewer main at Nucor Corp.'s steel plant. This in turn damaged the city's sewage system, prompting officials to issue water restrictions for 100,000 people. Flooding in the city damaged or destroyed 45 homes. Damage to the sewer system alone is estimated at $1.5–4 million.[61][62]

Alabama Power deployed more than 200 linemen to restore service, as soon as the storm passed. Power was restored to "all customers that could safely accept it" by the evening of June 20.[63] Governor Kay Ivey declared a state of emergency for Baldwin, Butler, Cherokee, DeKalb, Escambia, Mobile, Monroe, and Tuscaloosa counties and declared East Brewton a disaster area, though federal funding would not be available pending an assessment of damage.[64][65][66] The Alabama Department of Revenue provided tax relief to residents and businesses the aforementioned counties.[67] In East Brewton, the American Red Cross provided food to victims and local churches provided cleanup supplies.[68] GoFundMe established a hub page for donations relating to Tropical Storm Claudette.[69] The city of Tuscaloosa approved $500,000 in funds for infrastructure repair and a further $750,000 would come from a recently implemented 1 cent sales tax. As of July 6, damage assessments across Alabama did not reach the $7.5 million threshold required for federal disaster assistance.[70] The United States Department of Agriculture provided aid to farmers and ranchers across the state.[71] Without federal aid available, the Government of Escambia County used millions of dollars of its own funds to assist relief efforts from the EF2 tornado.[72]

Naperville–Woodridge tornado

[edit]

On the evening of June 20, 2021, an intense QLCS tornado affected the Chicago suburbs of Naperville, Woodridge, Darien, Burr Ridge, and Willow Springs in DuPage and Cook Counties in Illinois. The tornado struck well after dark and was rated an EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, with estimated wind speeds of up to 140 miles per hour (230 km/h). It had a path length of 14.8 mi (23.8 km) and reached a width of 600 yd (550 m), while causing 11 injuries, downing thousands of trees, and inflicting significant structural damage primarily across Naperville and Woodridge.[73]

In the immediate aftermath, the damage was described as "extensive", with 900 properties damaged, 300 of which were considered significantly damaged, and 29 deemed uninhabitable.[73] On June 22, Alicia Tate-Nadeau, director of the Illinois Emergency Management Agency, toured storm damage in Naperville and Woodridge with DuPage county officials.[74] On June 27, Brian McDaniel of the Illinois River Valley Red Cross met with county officials and opened the Multi-Agency Resource Center, where over 1,000 volunteers assisted to provide aid to those affected by the tornado. The center was opened for two days.[74] The non-profit group Naperville Tornado Relief was established in the aftermath of the event. They planned to raise $1.5 million to assist in cleanup of properties affected by the tornado. This goal was augmented in January 2023 by Illinois House Bill 969, which awarded the group $1 million.[75][76] By May 2024, 66 yards across Naperville had been replaced by the group.[77]

Western North America heat wave

[edit]Dixie Fire

[edit]Caldor Fire

[edit]Hurricane Ida

[edit]Tornado outbreak of December 10–11

[edit]Employees were kept at an Amazon Warehouse in Edwardsville, Illinois, despite warnings being issued for the area well in advance.[78]

December 2021 Midwest derecho and tornado outbreak

[edit]Marshall Fire (2021–22)

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Morgan, Leigh (2021-01-28). "National Weather Service releases interactive map that tracks the Fultondale EF-3 tornado". AL. Retrieved 2025-05-13.

- ^ Robinson, Carol (2021-02-04). "Rescuers recount in-the-field amputation that saved life of trapped Alabama tornado victim". al. Retrieved 2025-05-13.

- ^ "Last year for Fultondale High School seniors dampened by deadly tornado, pandemic". WIAT. 2021-02-04. Archived from the original on 2021-02-21. Retrieved 2025-05-13.

- ^ Bell, Valerie (2022-11-29). "'Time brings only change:' Nearly 2 years after tornado, Fultondale pushes forward". WBMA. Retrieved 2025-05-13.

- ^ Travis Caldwell, Keith Allen and Eric Levenson (February 18, 2021). "The Texas power grid is improving. But days of outages have caused heat, water and food shortages". CNN. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ meteorologists, weather.com (February 9, 2021). "Significant Ice Storm Possible From Southern Plains to Virginia as More Snow Blankets Midwest, East". The Weather Channel. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "6 Dead, Dozens Injured After Pileup Of Over 130 Vehicles On I-35W In Fort Worth". CBS News. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ NTSB releases factual report on 2021 fatal, 133-car pileup crash on I-35W in Fort Worth, WFAA, January 18, 2023

- ^ "Global Catastrophe Recap – February 2021" (PDF). Aon Benfield. March 10, 2021. p. 4. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ ICE STORM WARNING: First of its kind for the Richmond area, WRIC

- ^ "Winter Storm Warnings: Widespread impacts in Portland, valley". Feb 13, 2021. Retrieved Feb 16, 2021.

- ^ "ICE STORM WARNING: First of its kind for the Richmond area". 8News. 2021-02-12. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- ^ "Major Winter Storm Spreading Snow, Damaging Ice From the South Into the Midwest and Northeast | The Weather Channel - Articles from The Weather Channel | weather.com". The Weather Channel. February 14, 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ^ "Seattle, Portland buried in heavy snowfall". February 14, 2021.

- ^ Hartley, James; Johnson, Kaley (2021-02-14). "Winter storm Uri brings snow to North Texas. But it also brings special dangers". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- ^ Texas Freezes from Winter Storm Uri - February 15 / 18, 2021. Disaster Compilations. February 19, 2021. Archived from the original on August 30, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Brian K. Sullivan; Nauren S. Malick (February 16, 2021). "5 Million Americans Have Lost Power From Texas to North Dakota After Devastating Winter Storm". Time. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Erin Douglas (February 20, 2021). "Gov. Greg Abbott wants power companies to "winterize". Texas' track record won't make that easy". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ Andrew Weber (July 14, 2021). "Texas Winter Storm Death Toll Goes Up To 210, Including 43 Deaths In Harris County". Houston Public Media. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Jan Wesner Childs (February 18, 2021). "Houston Faces Dire Water Issues as Power Outages, Cold Push Texans To Their Limits". weather.com. The Weather Company. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Man killed in crash involving semi-truck in northern Oklahoma". KOCO News. February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "20 deaths blamed on cold weather in north as another front moves in". Mexico News Daily. February 19, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Estrada, Jesús (February 16, 2021). "Tormenta invernal deja 12 muertos en estados del norte". jornada.com.mx (in Spanish). La Jornada. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b 2021 Winter Storm Uri After-Action Review: Findings Report (PDF) (Report). City of Austin & Travis County. November 4, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ 2021 U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in historical context, Climate.gov, January 24, 2022

- ^ NWS Little Rock [@NWSLittleRock] (February 17, 2021). "We still have a lot of work to do as far as collecting snow reports, but we have roughed out a preliminary accumulation map for this latest event. There was over a foot of snow in parts of southern Arkansas. #arwx https://t.co/37l1QXncM4" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Winter Storm Viola Grips the East (PHOTOS) | The Weather Channel - Articles from The Weather Channel | weather.com". The Weather Channel. February 18, 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Winter Storm Winding Down in the East, South After Smashing All-Time Snow Record in Del Rio, Texas | The Weather Channel - Articles from The Weather Channel | weather.com". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Another storm plasters Mississippi to Massachusetts with ice, snow".

- ^ Yaron Steinbuch (February 17, 2021). "At least 23 dead as brutal cold from historic storm ravages Texas". New York Post. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "20 deaths blamed on cold weather in north as another front moves in". Mexico News Daily. February 19, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Erin Douglas (February 20, 2021). "Gov. Greg Abbott wants power companies to "winterize." Texas' track record won't make that easy". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Will; Robertson, Campbell (2021-02-17). "Burst Pipes and Power Outages in Battered Texas". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Sullivan, Brian K.; Malick, Nauren S. (February 16, 2021). "5 Million Americans Have Lost Power From Texas to North Dakota After Devastating Winter Storm". Time. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "How Many Millions Are Without Power in Texas?". Time. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Patrick Svitek (January 2, 2022). "Texas puts final estimate of winter storm death toll at 246". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Peter Aldhous, Stephanie M. Lee and Zahra Hirji (May 26, 2021). "The Texas Winter Storm And Power Outages Killed Hundreds More People Than The State Says". Buzzfeed News. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Shepherd, Katie. "Rick Perry says Texans would accept even longer power outages 'to keep the federal government out of their business'". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- ^ Aronoff, Kate (2021-02-16). "Conservatives Are Seriously Accusing Wind Turbines of Killing People in the Texas Blackouts". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Penney, Veronica (February 19, 2021). "How Texas' Power Generation Failed During the Storm, In Charts". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Searcey, Dionne (2021-02-17). "No, Wind Farms Aren't the Main Cause of the Texas Blackouts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Galbraith, Kate (2011-02-08). "Texplainer: Why does Texas have its own power grid?". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b Multiple sources:

- McLaughlin, Tim; Kelly, Stephanie (February 22, 2021). "Why a predictable cold snap crippled the Texas power grid". Reuters.

- "Why Texas Broke: The Crisis That Sank the State Has No Easy Fix". Bloomberg L.P. February 25, 2021.

- Englund, Will; Mufson, Steven; Grandoni, Dino. "Texas, the go-it-alone state, is rattled by the failure to keep the lights on". The Washington Post.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Calma, Justine (2021-02-17). "Texas has work to do to avoid another energy crisis". The Verge. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- Blackmon, David. "Texas Must Fix Its Chronic Power Grid Resiliency Issues Or Risk Becoming Another California". Forbes. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- Krauss, Clifford; Fernandez, Manny; Penn, Ivan; Rojas, Rick (2021-02-21). "How Texas' Drive for Energy Independence Set It Up for Disaster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- ^ "Texas Was Warned a Decade Ago Its Grid Was Unready for Cold". Bloomberg L.P. 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2021-03-02.

- ^ McCullough, Erin Douglas, Kate McGee and Jolie (2021-02-18). "Texas leaders failed to heed warnings that left the state's power grid vulnerable to winter extremes, experts say". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved 2021-03-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Gold, Russell (February 2022). "The Texas Electric Grid Failure Was a Warm-up". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ Douglas, Erin (February 18, 2021). "Texas was 'seconds and minutes' away from catastrophic monthslong blackouts, officials say". Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Brad (2021-02-24). "Texas Grid Was 4 Minutes and 37 Seconds from a Statewide Blackout, Per ERCOT". The Texan. Retrieved 2024-07-12.

- ^ "Gas and power sellers rack up billions in profit from Texas freeze". Reuters. 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ Douglas, Erin; Ferman, Mitchell (March 4, 2021). "ERCOT overcharged power companies $16 billion for electricity during winter freeze, firm says". The Texas Tribune.

Companies then buy power from the wholesale market to deliver to consumers, which they are contractually obligated to do. Because ERCOT failed to bring prices back down on time, companies had to buy power in the market at inflated prices.

- ^ "Governor Abbott Declares ERCOT Reform An Emergency Item". Office of the Texas Governor. February 16, 2021. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021.

- ^ Reimann, Nicholas. "Congressional Investigation Launched Into Texas Power Outages". Forbes. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ Hutchison, Cole (July 12, 2024). "Texas Supreme Court Issues Electric Opinion on PUC Orders During Winter Storm Uri". JD Supra.

- ^ Irwin, Lauren (2024-04-03). "Texas appeals court says winter storm lawsuits against transmission and distribution utilities can move forward". The Hill. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ "Texas appeals court allows some lawsuits against power companies related to 2021 winter storm to move forward". wfaa.com. 2024-04-06. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ "Two Claims Remain in Electric Transmission Defendants Winter Storm MDL". Texas Lawyer. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ Papin, Philippe; Berg (January 6, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Claudette (AL032021) (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ "Central Alabama Impacts from Claudette June 19-20, 2021". National Weather Service Forecast Office in Birmingham, Alabama. June 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Morton, Jason (June 23, 2021). "Repairing storm Claudette's destruction could cost $4 million, Tuscaloosa officials say". The Tuscaloosa News. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Tuscaloosa water, sewer pipe repairs after Claudette might cost $1.5 million". AL.com. The Associated Press. June 25, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Sharp, John (June 24, 2021). "East Brewton tornado: Power restored quickly, but search on for homeowners". AL.com. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Easterwood, Gabby (June 23, 2021). "Gov. Kay Ivey visits East Brewton to view tornado damage". WKRG. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Derrick Bryson (June 28, 2021). "Tropical Storm Claudette Expected to Weaken After Causing Deaths and Damage". The New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Helean, Jack (June 21, 2021). "Alabama under State of Emergency after Claudette". WTVC. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "ALDOR Announces Relief for Taxpayers Affected by Tropical Storm Claudette". Alabama Department of Revenue. June 23, 2021. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ "Claudette's final tornado tally reaches seven across four states". WNCT. The Associated Press. June 22, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Carol (June 23, 2021). "Tropical Storm Claudette: GoFundMe launches donation hub to help victims". AL.com. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Ryan (July 6, 2021). "Officials Estimate Nearly $3M In Flood Damage In Northport". Patch Media. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "USDA Assists Farmers, Ranchers, and Communities Affected by Tropical Storm Claudette" (Press release). United States Department of Agriculture. June 24, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Rupolo, John (July 19, 2021). "East Brewton high school still recovering 1 month after Tropical Storm Claudette". WEAR-TV. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "June 20-21, 2021: Late Night Tornadoes and Wind Damage, Including an EF-3 Tornado From Naperville to Willow Springs". National Weather Service Chicago, Illinois.

- ^ a b DuPage County District 3 Updates for Summer 2021 (Report). DuPage County, Illinois. 29 June 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Joe (13 January 2023). "$1 million awarded to Naperville tornado relief". Naperville Community Television.

- ^ "Naperville news: Residents still cleaning up after 2021 tornado; group secures $1.5M in funding". ABC7 Chicago. 2023-08-24. Retrieved 2024-10-10.

- ^ "2024 State of the City Address, Naperville, IL". Positively Naperville. City of Naperville. 8 May 2024. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "National Weather Service Raw Text Product". December 10, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2025.