Draft:Hội An Ancient Town

| Submission declined on 5 June 2025 by Mwwv (talk). Thank you for your submission, but the subject of this article already exists in Wikipedia. You can find it and improve it at Hội An instead.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Hội An Ancient Town | |

| Location | Quảng Nam Province, Vietnam |

| Criteria | (ii)(v) |

| Reference | 948 |

| Inscription | 1999 (23rd Session) |

| Extensions | 30 hectares (74 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 280 hectares (690 acres) |

| Website | http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/948 |

| Coordinates | 15°53′0″N 108°20′0″E / 15.88333°N 108.33333°E |

Hội An Ancient Town[1] (in Vietnamese: Phố cổ Hội An) is a historic town located in Quảng Nam Province, Vietnam, along the coast near the mouth of the Thu Bồn River, approximately 30 kilometers from Đà Nẵng. Its favorable geography and climate made Hội An a bustling international trading port in the 17th and 18th centuries, attracting merchants from Japan, China, and Western countries. The town also preserves remnants of earlier Champa trading ports along the Maritime Silk Road. By the 19th century, silting of the river and the French colonial preference for developing Đà Nẵng as a primary port led to Hội An's decline as a commercial hub. Remarkably, the town escaped destruction during wars and the rapid urbanization of the late 20th century. Since the 1980s, Hội An's architectural and cultural significance has gained recognition, making it one of Vietnam's most captivating tourist destinations.

Hội An Ancient Town is an exceptionally well-preserved example of a traditional Southeast Asian trading port. Its buildings, primarily traditional wooden structures from the 17th to 19th centuries, line narrow streets and reflect the town's historical development. Interspersed among residential buildings are religious and cultural structures that illustrate the town's formation, growth, and decline. Hội An is a cultural melting pot, blending Vietnamese traditions with Chinese community halls and temples, as well as French colonial architecture. Beyond its architectural heritage, the town maintains a rich intangible culture, including daily customs, beliefs, folk arts, and festivals. Widely regarded as a living museum of architecture and urban life, Hội An was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999 at the 23rd session of the World Heritage Committee for its outstanding universal value based on two criteria:[1][2]

- Hội An exemplifies cultural fusion as a result of its role as an international maritime commercial center.

- Hội An is an outstanding example of a well-preserved traditional Asian trading port.

Etymology

[edit]The name "Hội An" appears early in historical records, though its precise origin is unclear. According to Dương Văn An's 1553 work Ô Châu Cận Lục, Điền Bàn County listed 66 villages, including Hoài Phố, Cẩm Phố, and Lai Nghi, but no mention of Hội An. A map by Lê dynasty official Đỗ Bá, Thiên Nam Tứ Chí Lộ Đồ Sách, records Hội An Citadel and Hội An Bridge. Inscriptions at the Phước Kiến Cave in the Marble Mountains mention Hội An three times. During Nguyễn Phúc Lan's rule, the Minh Hương village was established near Hội An village. Records from the Minh Mạng era indicate that Hội An comprised six villages: Hội An, Minh Hương, Cổ Trai, Đông An, Diêm Hộ, and Hoài Phố. French scholar Albert Sallet noted that Hội An village was the most significant among five villages (Hội An, Cẩm Phố, Phong Niên, Minh Hương, and An Thọ).[3]

Westerners historically referred to Hội An as "Faifo." The origin of this name is debated. The 1651 Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum by missionary Alexandre de Rhodes defines Hoài Phố as a Japanese settlement in Cochinchina, also called Faifo.[4] Some suggest Faifo derives from "Hội An Phố" (Hội An Town), a name found in Vietnamese and Chinese historical records. Another theory posits that the Thu Bồn River, once called Hoài Phố River, evolved into Phai Phố and then Faifo through phonetic shifts.[5] Western missionaries and scholars used variations like Faifo, Faifoo, Fayfoo, Faiso, and Facfo in their records. Alexandre de Rhodes' 1651 map of Annam, including Đàng Trong and Đàng Ngoài, clearly marks "Haifo." French colonial maps later consistently used "Faifo" for Hội An.[6]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

Hội An Ancient Town is situated near the mouth of the Thu Bồn River, Quảng Nam Province's largest river, now slightly inland due to silting. The Thu Bồn River, flowing into the South China Sea, branches into several tributaries, including the Hội An River that runs through the town, alongside the Cẩm Nam and Cẩm Kim rivers.[7] Historical maps from the 17th and 18th centuries show Hội An on the northern bank, connected to the sea via the Đại Chiêm Estuary and linked to Đà Nẵng's Đại Estuary by another river. The ancient Cổ Cò-Đế Võng River served as a navigable waterway between Hội An and the Hàn River estuary, with archaeological evidence of sunken ships and anchors found in its riverbed.[8]

Though the name "Hội An" emerged around the late 16th century, the area's history is far older, having been home to the Sa Huỳnh culture and Champa culture. The Sa Huỳnh culture, first identified by French archaeologists in Quảng Ngãi Province, was confirmed as a distinct culture by Madeleine Colani in 1937. Over 50 Sa Huỳnh sites have been found in Hội An, mostly along ancient Thu Bồn River sand dunes.[9] Artifacts, including Han dynasty coins and Western Han-style iron tools, indicate trade as early as the 1st century BCE.[10] Notably, only late Sa Huỳnh culture is evident in Hội An, suggesting its prominence in this period.[11][10]

From the 2nd to 15th centuries, the region was under the Champa kingdom, characterized by Hindu temple complexes, including those in the Thu Bồn River basin. The political center Trà Kiệu and religious center Mỹ Sơn were prominent,[12] with Champa towers, wells, and sculptures, as well as artifacts from China, the Middle East, and Đại Việt, supporting the hypothesis of a Cham port at Lâm Ấp Thành.[10] After repeated conflicts, Champa was gradually pushed south by Đại Việt, with its final capital at Bầu Giá (Bình Định Province) overtaken in 1471 by the Later Lê dynasty. Hội An then came under Đại Việt control, laying the foundation for its later commercial prosperity.[12]

Hội An period

[edit]Emergence and prosperity

[edit]Hội An emerged in the late 16th century under the Later Lê dynasty. In 1527, Mạc Đăng Dung established the Mạc dynasty, controlling Hanoi. In 1533, Nguyễn Kim rallied forces under the Lê banner to oppose the Mạc. After Nguyễn Kim's death, his son-in-law Trịnh Kiểm took power, marginalizing the Nguyễn family. In 1558, Nguyễn Kim's son Nguyễn Hoàng relocated to Thuận Hóa, fortifying the region. After 1570, the Nguyễn continued to govern Quảng Nam.[13] Nguyễn Hoàng and his son Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên built fortifications, focused on developing the Đàng Trong economy, and expanded foreign trade, transforming Hội An into Southeast Asia's busiest international trading port at the time.[14]

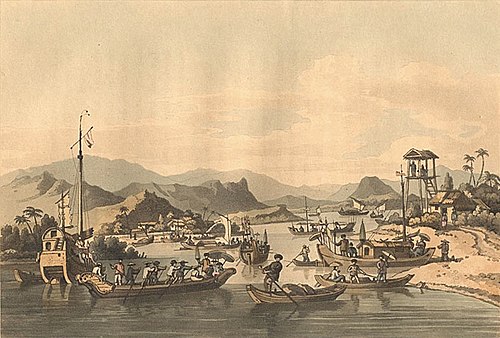

In the 17th century, the Nguyễn lords continued their conflict with the Trịnh lords while expanding south, encroaching on Champa territories. The Nguyễn issued laws to protect foreign trade, fostering expatriate settlements.[15] In 1567, the Ming dynasty lifted its isolationist policies, enabling trade with Southeast Asia but restricting certain exports to Japan. This prompted the Toyotomi regime and Tokugawa shogunate to seek Chinese goods through Southeast Asian ports.[16] From 1604 to 1635, at least 356 Japanese merchant ships ventured to Southeast Asia,[15] with 75 docking at Hội An within 30 years, compared to 37 at Tonkin under Trịnh control.[17] Japanese merchants traded hardware and daily goods for sugar, silk, and agarwood. By 1617, a Japanese quarter formed in Hội An, flourishing in the early 17th century.[15][18] A painting by Chaya Shinroku, Map of Cochinchina Trade Routes, depicts two- and three-story wooden structures in the Japanese quarter.[15] In 1651, Dutch captain Delft Haven noted about 60 closely built Japanese-style stone houses along the river, designed for fire prevention.[19] However, the Tokugawa shogunate's renewed isolationism and persecution of Christians led to a decline in the Japanese presence, with Chinese merchants gradually taking over.[15][20]

Unlike the Japanese, Chinese merchants were familiar with Hội An due to earlier trade with Champa. After Champa's fall, Chinese traders continued commerce with Vietnamese locals, driven by demand for salt, gold, and cinnamon from Southeast Asia.[21] Following the Late Ming peasant rebellions and the Ming-Qing transition, many Chinese immigrated to central Vietnam, establishing Minh Hương communities. Chinese merchants increasingly settled in Hội An, replacing the Japanese. The port became a hub for foreign goods, with the riverside Đại Đường district spanning several kilometers, bustling with shops. Most Chinese merchants, primarily from Fujian, wore Ming-style clothing and often married Vietnamese women.[22] Some became Vietnamese citizens, while others, known as "guest residents", retained Chinese nationality.[23] In 1695, Thomas Bowyer of the English East India Company attempted to establish a settlement in Hội An. Though unsuccessful, he recorded:[22]

The Faifo district features a street near the river lined with hundreds of houses. Only four or five are Japanese-style; the rest are Chinese. Previously, the Japanese dominated the district and its commerce. Now, the Chinese have taken over most commercial activities. Though less busy than before, 10 to 12 ships from Japan, Guangdong, Siam, Cambodia, Manila, and even Indonesia still trade here annually.

Decline and modern era

[edit]

During the 18th-century Tây Sơn rebellion, the Trịnh seized Quảng Nam in 1775, plunging Hội An into conflict.[24] The Trịnh army destroyed much of the commercial district, sparing only religious structures.[25] Many Nguyễn elites and wealthy Chinese merchants fled south to Saigon-Chợ Lớn, leaving Hội An in ruins.[26] In 1778, Englishman Charles Chapman lamented:[27]

Arriving at Hội An, we found the city's well-planned brick houses gone, its paved roads desolate, a painful sight. These works now exist only in memory.

About five years later, Hội An's new port slowly revived, though trade never regained its former prominence. Vietnamese and Chinese residents rebuilt from the rubble, erecting new houses and erasing traces of the Japanese quarter.[28]

In the 19th century, the Đại Estuary narrowed, and the Cổ Cò River suffered from silting, preventing large ships from docking. The Nguyễn dynasty's isolationist policies, restricting Western trade, further diminished Hội An's role as an international port.[29] However, the town continued as a local commercial center, with new roads and widened streets on the southern bank.[27] In the fifth year of Minh Mạng's reign, the emperor noted Hội An's diminished prosperity but acknowledged it remained more vibrant than other Vietnamese towns.[26] In 1888, when Đà Nẵng became a French concession, many Chinese merchants relocated there,[30] reducing Hội An's commercial activity. Nonetheless, most surviving residences and community halls took their current architectural form during this period.[31]

In the early 20th century, despite losing its port function, Hội An remained Quảng Nam's urban and administrative center. When Quảng Nam-Đà Nẵng Province was established in 1976, Đà Nẵng became the provincial capital, and Hội An faded into obscurity.[30] Fortunately, this spared the town from Vietnam's rapid 20th-century urbanization.[32] From the 1980s, scholars from Vietnam, Japan, and the West began studying Hội An. At the 23rd World Heritage Committee session in Marrakesh from November 29 to December 4, 1999, UNESCO designated Hội An Ancient Town a World Heritage Site. Today, tourism has revitalized the town, making it a thriving cultural destination.[14]

Architecture

[edit]Ancient town

[edit]The ancient town, located in Minh An Ward, spans about 2 square kilometers with short, winding streets in a chessboard pattern. Near the riverbank is Bạch Đằng Street, while Nguyễn Thái Học and Trần Phú streets connect to Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Street via the Japanese Bridge. The terrain slopes gently from north to south, causing streets like Nguyễn Huệ, Lê Lợi, Hoàng Văn Thụ, and Trần Quý Cáp to incline slightly inland.[33] Trần Phú Street, historically the main thoroughfare from the Japanese Bridge to the Chaozhou Community Hall, was named Rue du Pont Japonnais during French colonial times.[34] Now about 5 meters wide, many houses lack porches due to late 19th- and early 20th-century expansions.[35] Nguyễn Thái Học Street, built in 1840 and later called Rue Cantonnais by the French, and Bạch Đằng Street, completed in 1878 and known as Riverside Street, formed through river sedimentation.[34] Phần Châu Trinh Street lies inside Trần Phú Street,[35] with numerous small alleys branching off perpendicularly.[36]

Trần Phú Street hosts the most iconic architectural works, including five Chinese community halls built to honor hometowns: Guangdong, Chinese, Fujian, Hainan, and Chaozhou, all with even-numbered addresses. At the corner of Trần Phú and Nguyễn Huệ streets stands the Quan Công Temple, a hallmark of Minh Hương architecture. Nearby, the Hội An History and Culture Museum, originally a Minh Hương temple dedicated to Guanyin, joins the Sa Huỳnh Culture Museum and the Trade Ceramics Museum on this street.[37] Beyond the Japanese Bridge, Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Street features well-preserved traditional houses with red-brick sidewalks, culminating in the Cẩm Phố communal house.[38] The western side of Nguyễn Thái Học Street features French-style facades, while the eastern side is a bustling shopping area with large two-story houses. The Hội An Folklore Museum at 33 Nguyễn Thái Học Street, the largest preserved residence, measures 57 meters long and 9 meters wide. This area often floods during the rainy season, requiring residents to use boats for shopping and dining.[39] The French quarter on the eastern side includes single-story European-style houses on Phan Bội Châu Street, once used as colonial civil servant dormitories.[40]

Traditional architecture

[edit]

Hội An's most common buildings are single- or two-story row houses, narrow and deep to suit the region's harsh climate and frequent flooding. Constructed with durable materials, these wooden structures with brick sidewalls are typically 4–8 meters wide and 10–40 meters deep, depending on the street.[41] A typical layout includes an entrance, porch, main house, annex, corridor, courtyard, another porch, three-room backyard, and rear garden. Some houses integrate commercial, living, and worship spaces for narrow settings.[42] These designs reflect Hội An's unique regional culture.[43]

The main house, divided by 16 pillars in a 4×4 grid, forms a 3×3 space. The central area, slightly larger, serves as a commercial space: the first section from the entrance to the courtyard, the second for storing goods behind a partition, and the third for an inward-facing shrine.[41] Inward-facing shrines are a key feature, though some face the street.[44] The annex, typically a low two-story building, is open to the street, separate from commercial activities, and used for receiving guests.[42] The corridor and courtyard, sometimes paved with stone or decorated with ponds and bonsai, connect the house's sections, adapting to the rainy and sunny climate. The backyard, enclosed by wooden walls, houses kitchens and bathrooms.[45] Shrines, often placed in lofts or central areas, are compact to avoid obstructing trade and daily activities.[46][47]

Hội An's houses often feature double roofs, with separate roofs for the main house, annex, and corridor.[44] Hội An tiles, made of clay, are thin, rough, square (about 22 cm per side), and slightly curved, arranged in alternating upward and downward rows, secured with mortar to form sturdy ridges.[48] Gabled roofs, sometimes with elevated sides, and ornate gables contribute to the town's architectural distinctiveness.[49]

| Type | Location | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Single-story wooden houses | Trần Phú and Lê Lợi streets | 18th–19th centuries |

| Two-story houses with porches | Trần Phú and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets | Late 19th–early 20th centuries |

| Two-story wooden houses with balconies | Nguyễn Thái Học and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets | Late 19th–early 20th centuries |

| Two-story brick houses | Nguyễn Thái Học and Trần Phú streets | Late 19th–early 20th centuries |

| French-style two-story houses | Nguyễn Thái Học Street | Early 20th century |

Architectural landmarks

[edit]Despite many buildings dating to the colonial period, Hội An preserves landmarks reflecting its historical rise and fall. From the 16th to early 18th centuries, buildings served practical purposes like docks, wells, temples, bridges, tombs, shrines, and shops.[51] From the 18th century, as the port declined, structures like Confucian temples, cultural sites, communal houses, churches, and community halls became prevalent, showcasing the town's transformation.[52] French colonial influences introduced blended architectural styles, harmonizing with urban spaces.[52][53] As of December 2000, Hội An's World Heritage Site included 1,360 relics: 1,068 ancient houses, 11 wells, 38 shrines, 19 pagodas, 43 temples, 23 city god pavilions, 44 special tombs, and one bridge, mostly within the ancient town[54].

Temples

[edit]

Hội An was once an early center of Buddhism in Đàng Trong, primarily hosting Hinayana Buddhist temples. Many temples trace their origins to ancient times, but due to continuous changes and renovations, most original structures no longer remain.[55] The earliest known temple, Chúc Thánh Temple, located about 2 kilometers north of the ancient town center, is said to date back to 1454.[56] It preserves numerous relics, statues, and inscriptions related to the introduction and development of Buddhism in Nội Đường.[57] In the suburbs of the ancient town, there are several relatively newer temples, such as Phước Lâm, Vạn Đức, Kim Bồng, and Viên Giác. In the early 20th century, many new temples were established, with the most notable being Long Tuyền Temple, built in 1909.[58] Beyond those built along ancient streams far from villages, Hội An also has village temples near settlements, forming an integral part of the community. This reflects the monks' attachment to the secular world and indicates the strong community cultural institutions of the Minh Hương society here.[59] The Hội An History and Culture Museum, located within the ancient town, was originally a 17th-century temple dedicated to Guanyin, constructed by Vietnamese and Minh Hương residents.[60]

Hội An's temples primarily honor the pioneers who founded the city, society, and the Minh Hương community. These temples, typically located in villages, are simple in design with a single entrance and three-bay layout, constructed from fire-resistant bricks, topped with yin-yang tiled roofs, and feature a central shrine.[61] The most representative is the Quan Công Temple, also known as Ông Temple, located at 24 Trần Phú Street in the heart of the ancient town. Built in 1653 by Minh Hương and Vietnamese residents to venerate Guan Yu, the "Paragon of Loyalty," the temple has retained its original appearance despite multiple renovations.[62] The Quan Công Temple consists of several buildings with green glazed tile roofs, divided into three sections: the front hall, courtyard, and main hall. The front hall stands out with its red paint, intricate decorations, and sturdy tiled roof, featuring two large doors adorned with blue dragon carvings coiled among clouds. Flanking the walls are a half-ton bronze bell and a large drum, gifted by Emperor Bảo Đại, mounted on a wooden frame.[63] The courtyard, decorated with rock gardens, creates a bright and airy atmosphere, with two additional halls on either side. A stone tablet embedded in the eastern wall records the temple’s first renovation in 1753.[64] The main hall, or rear hall, is dedicated to worship, housing a nearly 3-meter-tall statue of Guan Yu, depicted with a red face, phoenix eyes, long beard, and clad in green robes while riding a white horse. Statues of his trusted aides, Guan Ping and Zhou Cang, stand on either side. Historically, the Quan Công Temple served as a religious hub for Hội An’s merchants, with Guan Yu’s sanctity fostering trust in commercial dealings. Today, the temple hosts vibrant festivals on the 13th and 14th of the sixth lunar first and sixth lunar months, known as the “Ông Temple Festival,” attracting numerous devotees and visitors.[65]

Clan shrines

[edit]As in many parts of Vietnam, every clan in Hội An maintains a place to honor ancestors, known as clan shrines or ancestral temples. These distinctive structures were established by prominent village clans at the founding of Hội An and passed down for ancestral worship. Smaller Chinese families often convert the residences of elders into shrines, with descendants responsible for offerings and maintenance as needed.[66] Most shrines are concentrated on Phan Châu Trinh and Lê Lợi streets, with a few scattered behind houses on Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai or Trần Phú streets.[67] Chinese immigrant shrines date back to the early 17th century, with only a small portion built after the 18th century.[66] Unlike rural counterparts, Hội An’s shrines typically exhibit an urban architectural style.[68] Designed as places for ancestor worship, these shrines are constructed in a garden-like form with strict layouts, incorporating gardens, gates, fences, and auxiliary buildings. Many are grand and ornately built, such as the Trần Clan Shrine, Trương Clan Shrine, Nguyễn Clan Shrine, and Minh Hương Ancestral Shrine.[69]

The Trần Clan Shrine, constructed in the early 19th century, is located at 21 Lê Lợi Street in Hội An. Like other clan shrines in the region, it is nestled within a 1,500-square-meter courtyard, surrounded by high walls and adorned with a front garden featuring bonsai, flowers, and fruit trees. The shrine's architecture blends Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese influences, built with precious timber in a two-entry, three-bay layout, topped with a sloping roof covered in yin-yang tiles. The interior is divided into two main sections: the primary area dedicated to ancestral worship and a secondary space for the clan leader’s residence and guest accommodations.[70] The worship area has three doors—left for men, right for women, and the central door reserved for elders during significant occasions. In front of the ancestral tablets, wooden boxes containing relics and genealogical records of the Trần Clan are arranged according to the family lineage. During festivals or ancestral commemoration days, the clan leader opens these boxes to honor the deceased. Behind the shrine lies the clan cemetery, planted with starfruit trees symbolizing the concept of "returning to one’s roots."[71]

Community Halls

[edit]One defining characteristic of Chinese immigrants is their tradition of establishing community halls in their places of residence abroad, based on shared regional origins, to provide spaces for communal activities and cultural practices. In Hội An, five such halls remain, each corresponding to a distinct immigrant group: Fujian, Chinese (general), Chaozhou, Hainan, and Guangdong. These large-scale halls are situated along the axis of Trần Phú Street, facing the Thu Bồn River.[72] Their traditional design includes a main gate, a courtyard decorated with bonsai and rock gardens, side temples, a ceremonial hall, and the grand main hall—the largest structure—featuring elaborate wood carvings, gold lacquer, and tiled roofs with painted ceramic figurines. Despite multiple renovations, the wooden frameworks retain many original elements. Beyond fostering hometown connections, these halls serve a vital religious function, with the deities worshipped varying according to the customs and traditions of each group’s homeland.[73]

Among Hội An’s five community halls, the Fujian Community Hall, located at 46 Trần Phú Street, is the largest. Originally a thatched-roof Buddhist temple built by Vietnamese locals in 1697, it fell into disrepair due to lack of maintenance. Fujian merchants purchased it in 1759, and after several renovations, transformed it into a community hall by 1792.[37] [74] The building is laid out in a “三” (trident-shaped) configuration, extending from Trần Phú Street to Phan Châu Trinh Street, comprising a main gate (tam quan), front courtyard, east and west wing buildings, main hall, rear courtyard, and rear hall. The current gate was reconstructed during a major renovation in the early 1970s.[75] The entrance is striking, with seven green glazed tile roofs arranged symmetrically. A white plaque with red inscriptions reading “Kim Sơn Temple” hangs beneath the upper roof, while a blue stone tablet with red seal script reading “Fujian Community Hall” is positioned under the lower roof. Walls on either side of the gate separate the inner and outer courtyards. The main hall is adorned with vermilion pillars and wooden urns praising the Heavenly Mother (Mazu), and enshrines a statue of Avalokiteśvara in meditative pose. In front of the Guanyin statue is a large incense burner, flanked by statues of Mazu’s guardians, Qianli Yan (Thousand-Mile Eye) and Shunfeng Er (Wind-Following Ear).[76] Crossing the rear courtyard leads to the rear hall, where the central shrine honors six Ming Dynasty generals from Fujian, with altars to the left for Zhusheng Niangniang (Goddess of Birth) and the Twelve Midwives, and to the right for the God of Wealth. Additionally, the rear hall commemorates donors who funded the construction of the community hall and Kim Sơn temple.[77] Every year on the 23rd day of the third lunar month, the Chinese community holds a festival for Mazu, featuring lion dances, fireworks, fortune-telling, prayers, and other rituals, attracting crowds from Hội An and beyond.[78]

| Name | Vietnamese name | Address | Community | Established |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian | Chùa Kim An | 46 Trần Phú Street | Fujian | 1792 |

| Chinese (Yangshang) | Chùa Ngũ Bang | 64 Trần Phú Street | Five Regions | 1741 |

| Chaozhou | Chùa Ông Bổn | 92 Nguyễn Duy Hiệu Street | Chaozhou | 1845 |

| Hainan | Chùa Hải Nam | 10 Trần Phú Street | Hainan | 1875 |

| Guangdong | Chùa Quảng Triệu | 176 Trần Phú Street | Guangdong | 1885 |

Japanese Bridge

[edit]

The only surviving ancient bridge, the Japanese Bridge (Chùa Cầu), spans a small tributary of the Thu Bồn River, connecting Trần Phú and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets.[80] Approximately 18 meters long, it is said to date to 1593, though evidence is inconclusive. It appears as "Hội An Bridge" in the 1630 Thiên Nam Tứ Chí Lộ Đồ Sách[17] and as the "Japanese Bridge" in Đại Nam's 1695 Overseas Chronicles.[81] Renovated in the 18th and 19th centuries,[82] its current form features enamel decorations typical of Nguyễn dynasty architecture.[83]

The Japanese Bridge features a distinctive "house-over-bridge" architectural style, with a house structure above and a bridge below, a design common in tropical Asian countries.[80] Despite its name, multiple renovations have left few traces of Japanese architectural elements.[83] The bridge’s striking appearance stems from its curved wooden roof supported by stone arch pillars. The bridge deck, shaped like a rainbow, is paved with wooden planks and features small wooden platforms on the sides, originally used for displaying goods. On the upstream side, a small temple dedicated to Xuân Vũ Đế (the God of the North) was constructed approximately half a century after the bridge’s completion. The bridge and temple are separated by a wooden wall and a door with a window above and panels below, creating a relatively independent space. Above the temple’s entrance hangs a red plaque inscribed with the words "Lai Viễn Kiều" (Bridge for Faraway Guests), penned by Nguyễn Phúc Chu in 1719. At each end of the bridge, animal statues adorn the bridgeheads: monkeys on one side and dogs on the other. Carved from jackfruit wood, each statue is accompanied by an incense bowl placed in front.[80] According to legend, a giant catfish, with its head in Japan, tail in the Indian Ocean, and body in Vietnam, causes earthquakes, natural disasters, and floods when disturbed. The Japanese are said to have built the bridge with monkey and dog deities to suppress this monster. Another hypothesis suggests the monkey and dog statues symbolize the construction period, beginning in the Year of the Monkey and ending in the Year of the Dog. This small bridge has become an iconic symbol of Hội An.[74]

Culture

[edit]Hội An stands out for its rich history and cultural diversity. Since the late 15th century, Vietnamese settlers coexisted with Cham residents, and the town's role as a trading port welcomed diverse cultures, fostering a multilayered cultural identity expressed through customs, literature, cuisine, and festivals.[84] Unlike the royal heritage of Huế, Hội An's culture is rooted in everyday life,[85] with vibrant intangible heritage complementing its physical landmarks.[86]

Beliefs

[edit]In addition to ancestor worship, Hội An residents practice the worship of the Five Deities (Ngũ Tế), rooted in the local belief that "the state has its king, and the house has its master." These Five Deities are considered the household guardians, believed to govern and arrange the family’s fate. The Vietnamese typically recognize these as the Kitchen God (Táo Thần), Well God (Tỉnh Thần), Door God (Môn Thần), Patron Saint (Bản Mệnh Tiên Sư), and the Nine Heavenly Maidens (Cửu Thiên Huyền Nữ). Some Chinese residents, however, identify them as the Kitchen God (Táo Quân), Door God (Môn Thần), Household God (Hộ Thần), Well God (Tỉnh Thần), and Central Deity (Trung Lưu). The altars for these Five Deities are solemnly placed in the center of the house, above the ancestral tablets.[87] In practice, each deity has a designated worship space within the household: the Kitchen God is venerated in the kitchen, the Door God at the entrance, and the Well God near the well. Chinese residents, however, do not worship the Kitchen God in the kitchen but place the altar in the courtyard, adjacent to the altar for the Heavenly Official (Thiên Quan) who grants blessings.[87]

Hội An’s religious landscape is diverse, encompassing Buddhism, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Caodaism, with Buddhism remaining the dominant faith. Many families, even those not formally religious, practice vegetarianism and venerate Buddhist figures, primarily Avalokiteśvara (Goddess of Mercy) and Gautama Buddha, with some also honoring Mahasthamaprapta. Buddhist altars are placed in solemn, purified spaces, typically elevated above ancestral altars. Some households dedicate significant space for Buddhist worship and scripture recitation.[88]

Another distinctive feature of Hội An’s folk beliefs is the widespread worship of Guan Yu (Quan Công), which, though rare in rural areas, is particularly prevalent in urban settings.[88] Among the many deities revered in Hội An, Guan Yu is regarded as the most sacred. The Quan Công Temple, located at the heart of the ancient town, is a focal point of this faith, with incense burning year-round. For generations, residents have prayed to Guan Yu for protection and family harmony. Altars often feature statues or images of Guan Yu alongside his aides, Guan Ping and Zhou Cang.[89]

In the cultural heritage of Chinese immigrants, particularly within community halls, the deities worshipped vary according to each group’s traditions. The Fujian Community Hall venerates Mazu (Heavenly Mother) and the Six Loyal Fujian Ministers of the Ming Dynasty. The Hainan Community Hall honors 108 merchants from Hainan who perished at sea while trading in Vietnam and were deified by the Nguyễn dynasty as Zhao Ying Gong (Protective Lords).[90] The Chaozhou Community Hall worships General Ma Yuan, the God of Waves, revered for rescuing merchant ships. Other forms of worship in Hội An include veneration of female spirits (Bà Cô), heroic figures (Ông Mãnh), anonymous spirits (Vô Danh Vô Vị), talismanic stones (Thờ Đá Bùa), and Shi Gandang (Thạch Cảm Đương), protective stone deities.[91]

Traditional festivals

[edit]

Hội An continues to preserve numerous traditional festivals, encompassing reverence for city gods, commemoration of ancestors, veneration of saints, and religious observances. Among the most representative is the City God Pavilion Festival held in suburban villages. Typically, each village has a pavilion dedicated to the City God and local pioneers. Every early spring, villages organize this festival to honor their City God and remember their forebears. The event is usually overseen by village elders, who, in preparation, form a festival committee. Villagers collectively contribute funds, participate in cleaning, and decorate the pavilion and temples. The festival spans two days: the first day marks the opening, while the second is the formal ceremonial day.[92]

On the 15th days of the first and seventh lunar months, Hội An residents hold Dragon Boat Festivals at rural city god pavilions. These dates coincide with the transition between the rainy and dry seasons, a period prone to epidemics. Local belief holds that diseases are caused by malevolent natural forces, prompting universal participation in the festival. On the ceremonial day, villagers row dragon boats to the pavilion, where the chief officiant blesses and consecrates the boats with holy water. After numerous rituals, at night, sturdy men transport the dragon boats to designated areas, where they are burned and released into the sea.[93]

In Hội An’s riverine and coastal fishing villages, canoe racing is an essential cultural activity, held from the second to seventh days of the first lunar month, praying for abundant catches in the second month and safety in the third. According to folk beliefs, boat racing pleases the deities of mountains and waters, bringing blessings to the community. Before each race, households diligently practice and prepare. Winning a race is a source of pride, symbolizing an impending bountiful harvest. While rituals and racing were once equally significant, today the competitive aspect often overshadows the ceremonial.[94] During the fishing season’s opening, residents of Hội An’s fishing villages also worship the Whale God (a blue whale revered for rescuing mariners).[Note 1] These rituals often feature bầu nậm singing, a distinctive folk music depicting life and labor on the river. As in other central Vietnamese coastal regions, when a whale beaches, fishermen bury it respectfully and conduct solemn rituals.[94]

Since 1998, the Hội An municipal government has hosted the Full Moon Festival on the 14th night of each lunar month, from 5 to 10 p.m. This unique initiative was proposed by Polish architect Kazimierz Kwiatkowski, who dedicated himself to preserving Hội An Ancient Town and Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary, both UNESCO World Heritage Sites. During the festival, all households, including shops and restaurants, turn off electric lights, allowing the moonlight and lanterns to illuminate the streets. Vehicles are prohibited, and the streets are reserved for pedestrians. Activities include music performances, folk games, chess, bầu nậm card-singing, and lantern displays. During major festivals, additional events such as masquerades, poetry recitals, and lion dances enhance the cultural experience. The Full Moon Festival immerses visitors in the ambiance of Hội An’s centuries-old heritage.[95]

Folk entertainment

[edit]

The music, theater, and folk games of Hội An are a testament to the ingenuity of its residents, developed through labor and preserved as vital components of local spiritual life. These include hò khoan (work chants), chèo chài (rowing chants), hò kéo neo (anchor-pulling chants), lý (lyrical folk tunes), vè (Vietnamese rhyming verses),[96] tuồng (classical opera), bầu nậm (ceremonial rowing songs), and hát bài chòi (card-singing games). Hội An also maintains traditions of playing ancient music during weddings and funerals, as well as performing đờn ca tài tử (southern amateur chamber music) alongside renowned artists.[97] Local folk games include card games, đánh đỏ (red stick gambling), scholar riddles, poetry, and calligraphy contests.

Hát bài chòi is a culturally significant recreational activity in Quảng Nam Province and Vietnam’s central coast, held on the 14th night of each lunar month in a small park at the intersection of Nguyễn Thái Học and Bạch Đằng streets. Eight to ten players sit in elevated thatched huts, divided into two teams, with a lead singer, known as the hiệu ca (caller), positioned at the head or center. Thirty-two cards, called hạ phó bài (lower deck cards), are evenly distributed among the players, with each receiving three cards inscribed with different words. These cards are printed on bamboo paper using woodblock techniques, coated with a layer of shell and stiff paper, and feature red, green, or blue-gray backs.[98] Two additional cards are reserved. The caller has a separate deck stored in a bamboo tube hung on a tree, drawing cards without seeing them and singing a verse for each to prompt players to guess the card.[98] When a player’s card matches the caller’s, they strike a wooden fish, and a “soldier” runner exchanges the card for a flag. The first player to collect three flags shouts “Tới!” (Got it!), ending the game. The caller is the heart of the game, requiring proficiency in folk songs and the ability to improvise poetic verses related to the card’s content, ensuring the game remains engaging and unpredictable.[99] This blend of performance and spontaneity is the primary allure of hát bài chòi.[98]

Hát Bả trạo a ceremonial folk singing form, plays a significant role in the spiritual and emotional life of Hội An’s residents.[100] Its performance structure narrates a boat’s journey from departure to safe landing, combining the narrative style of tuồng opera, a theatrical form beloved in Quảng Nam.[101] Beyond its artistic depiction of rowing, bầu nậm boasts a rich variety of singing techniques, including standard methods like chanting and calling, as well as folk styles such as hò khoan, lý, low murmurs, and high-pitched songs. The performers’ talent makes it highly captivating for audiences.[100] During the Whale God Festival (Lễ Hội Cá Ông), fishermen sing bầu nậm to express reverence and mourning for “Ngọc Lân Nam Hải,” the deity believed to rescue distressed mariners, while praying for calm seas and safe voyages. Coastal residents also perform bầu nậm at funerals, lamenting tragic fates and honoring the deceased’s virtues.[100]

Cuisine

[edit]

For centuries, Hội An’s position at the crossroads of waterways and its role as a hub of economic and cultural exchange have fostered a diverse culinary tradition influenced by Vietnamese, Chinese, Japanese, and Western cultures.[102] Although the region lacks the vast expanses of the Mekong or Red River Deltas, its fertile riverbank dunes and narrow alluvial lands shape local lifestyles and customs, including culinary practices.[103] Seafood dominates Hội An’s daily diet, with fish and other marine products often outselling other meats by double in local markets.[102] Fish is so integral that markets are commonly referred to as “fish markets.”[104] Hội An’s Chinese community continues to preserve traditional Chinese cooking habits and customs. During festivals and weddings, they prepare signature dishes such as Fujian fried noodles, Yangzhou fried rice, and “money chicken,” which serve as opportunities to strengthen community bonds. The Chinese have significantly enriched Hội An’s culinary landscape, contributing to the creation of many unique local dishes.[105]

One of Hội An’s most iconic dishes is cao lầu, a noodle dish whose origins and name remain uncertain. Local Chinese residents do not claim it as a Chinese dish. Some Japanese researchers note similarities with noodles from the Ise region, but the flavor and preparation methods differ significantly.[106] Preparing cao lầu is labor-intensive: rice is soaked, filtered, and ground into a wet flour, then repeatedly dried with cloth, shaped into medium-sized blocks, and cut into noodles. Unlike many noodle dishes, cao lầu is served without broth, mixed with roast pork, sauce, and pork rind. It is typically accompanied by bean sprouts and lettuce to balance its richness. When served, the noodles are placed in a bowl, topped with roast pork or cured meat, pork rind, and a spoonful of fried pork fat for added flavor.[107]

In the past, Hội An was home to many cao lầu vendors, with notable ones including Ông Cảnh (Mr. Cảnh) and Năm Cơ (Old Fifth Cơ).[Note 2] Their fame is celebrated in a local folk rhyme:[108][109]

Hội An has its own "Hawaii"—the Lai Viễn Bridge, Bổn Đầu Temple, and Old Fifth Cơ’s cao lầu.

In addition to cao lầu, Hội An is renowned for dishes like wonton and white rose dumplings, alongside a variety of rustic specialties such as steamed rice cakes, mussels, pancakes, rice paper, and notably Quảng noodles (mì Quảng). As the name suggests, Quảng noodles originate from Quảng Nam Province. Like phở and bún, they are made from rice but possess a distinct color, aroma, and flavor.[110] The preparation begins with soaking high-quality rice in water to soften it, grinding it into fine flour, and adding alum to make the dough crisp and firm. The dough is pressed into flat, leaf-shaped cakes, which are boiled, cooled, lightly oiled to prevent sticking, and cut into noodles. The broth is typically made from shrimp, pork, or chicken, though snakehead fish or beef may also be used, resulting in a clear, sweet, and non-spicy flavor.[111] Quảng noodles are ubiquitous in Hội An, from urban restaurants to rural street stalls, particularly at roadside noodle shops.[112]

White rose dumplings are an exquisite, delicious, and unique dish of Hội An’s ancient town, consisting of two types of rice flour-based delicacies: bánh bao (steamed dumplings) and bánh vạc (boiled dumplings). The preparation is meticulous, starting with the selection of premium rice, which is sifted and ground with water into fine rice flour.[113] The grinding water must be pure, unsalted, and free of alum, typically sourced from the ancient Bá Lễ Well. The rice flour is ground multiple times and poured into clean basins. While grinding, workers prepare the fillings and fried onions. The fillings differ between the two dumplings: bánh bao’s filling is primarily made by pounding shrimp and spices in a mortar, while bánh vạc’s filling is more diverse, including shrimp paste, bean sprouts, wood ear mushrooms, bamboo shoots, diced pork, and green onions, all stir-fried with salt and fish sauce.[114] Each type is crafted by two to four dedicated artisans. Bánh bao’s skin is extremely thin, resembling white rose petals, while bánh vạc is larger, shaped like a pot handle.[115] After being filled, the dumplings are steamed for 10 to 15 minutes. Both are served together, allowing diners to enjoy them as preferred. The presentation is elegant, with bánh bao typically placed centrally on the top layer and bánh vạc arranged around the bottom, sprinkled with fried onions and drizzled with cooked oil.[116] White rose dumplings are paired with a distinctive fish sauce that balances the sweet flavor of shrimp, the tang of lemon, and the spice of yellow chili slices.[117]

Hội An’s restaurants are not only known for their delectable cuisine but also for their distinctive ambiance. Many eateries in the ancient town are decorated with antique paintings, surrounded by ornamental potted plants, bonsai, or handicrafts. Some feature fishponds or rock gardens, creating a relaxing and comfortable environment for diners. Restaurant names often carry traditional significance, passed down through generations.[118] Beyond local specialties, French, Japanese, and Western dishes and customs have been preserved and developed, contributing to the diversity of Hội An’s culinary scene and catering to the varied preferences of tourists.[105]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The worship of Ông Cá (Tục thờ cá Ông), or the Whale God, is widespread along the Vietnamese coast. Ông Cá refers to the blue whale.

- ^ According to the southern Vietnamese custom, this person is actually the fourth child in the family.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Hoi An Ancient Town". UNESCO Silk Road Programme. Archived from the original on 2021-07-16. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ Nguyễn 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 207.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 206.

- ^ Đặng 1991, p. 190.

- ^ Đặng 1991, p. 191.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Hoàng 2001, p. 393.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Lê 2008, p. 116.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 21.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b Lê 2008, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Hoàng 2001, p. 399.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Nguyễn 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Nguyễn 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Nguyễn 2008, p. 24.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Fukukawa 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 31.

- ^ a b Nguyễn 2008, p. 36.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 33.

- ^ a b Nguyễn 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Nguyễn Thế 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 119.

- ^ a b Nguyễn 2008, p. 46.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 12.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Nguyễn 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Nguyễn 2007, p. 24,26.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 15.

- ^ a b Tạ Thị 2007, p. 136.

- ^ a b Tạ Thị 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 144.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 143.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 138.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 137.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 135.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 136.

- ^ Nguyễn 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 102.

- ^ a b Tạ Thị 2007, p. 135.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 130.

- ^ Nguyễn Thế 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Nguyễn Thế 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Nguyễn 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Đặng 1991, p. 344.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 218.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 69.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 138.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 207.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 140.

- ^ a b Tạ Thị 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Nguyễn 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 76.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 135.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 112,114.

- ^ Đặng 1991, p. 346.

- ^ a b Lê 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 226.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 123.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2004, p. 236.

- ^ Tạ Thị 2007, p. 113.

- ^ a b c Lê 2008, p. 121.

- ^ Nguyễn 1995, p. 55.

- ^ Lê 2008, p. 120.

- ^ a b Fukukawa & al. 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 102.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 104.

- ^ a b Bùi 2005, p. 38.

- ^ a b Bùi 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Nguyễn Phước 2001, p. 26.

- ^ a b Nguyễn Thế 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Nguyễn Thế 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Hoàng Thị, Thu Thủy. Đặc điểm của từ điển song ngữ Việt-Hán hiện đại [Characteristics of Modern Vietnamese-Chinese Bilingual Dictionaries] (in Vietnamese). Chỉ Thiện.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Bùi 2005, p. 58.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Bùi 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Bùi 2005, p. 62.

- ^ a b Bùi 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 12.

- ^ a b Bùi 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 31.

- ^ "Hội An City People's Committee". hoian.gov.vn (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 27.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 28.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 103.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 104.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 105.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 106.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 107.

- ^ Trần 2000, p. 138,139.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nguyễn Phước, Tương (2004). Hội An - Di sản thế giới [Hội An - World Heritage] (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City: Nhà xuất bản Văn nghệ.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hoàng, Minh Nhân (2001). Hội An - Di sản văn hóa thế giới [Hội An - World Cultural Heritage] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Thanh Niên.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nguyễn, Văn Xuân (2008). Hội An [Hội An] (in Vietnamese). Đà Nẵng: Nhà xuất bản Đà Nẵng.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nguyễn, Chí Trung (2007). Di tích - danh thắng Hội An [Hội An Relics and Scenic Spots] (in Vietnamese). Quảng Nam: Trung tâm Quản lý Bảo tồn Di tích Hội An.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lê, Tuấn Anh (2008). Di sản thế giới ở Việt Nam [World Heritage Sites in Vietnam] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Văn hóa Thông tin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nguyễn Thế, Thiên Trang (2001). Hội An - Di sản thế giới [Hội An - World Heritage] (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City: Nhà xuất bản Trẻ.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Đặng, Việt Ngoạn (1991). Đô thị cổ Hội An [Hội An Ancient Town] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Khoa học Xã hội.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nguyễn, Quốc Hùng (1995). Phố cổ Hội An và việc giao lưu văn hóa ở Việt Nam [Hội An Ancient Town and Cultural Exchange in Vietnam] (in Vietnamese). Đà Nẵng: Nhà xuất bản Đà Nẵng. OCLC 473244874.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bùi, Quang Thắng (2005). Văn hóa phi vật thể ở Hội An [Intangible Culture in Hội An] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Thế giới. OCLC 470974393.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Trần, Văn An (2000). Văn hóa ẩm thực ở phố cổ Hội An [Culinary Culture in Hội An Ancient Town] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Khoa học Xã hội.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Tạ Thị, Hoàng Vân (2007). Di tích kiến trúc Hội An trong tiến trình lịch sử [Hội An Architectural Relics in Historical Context] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Đại học Quốc gia Hà Nội. Archived from the original on 2024-04-24. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- Fukukawa, Yuichi; et al. (2006). Kiến trúc phố cổ Hội An - Việt Nam [Architecture of Hội An Ancient Town - Vietnam] (in Vietnamese). Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Thế giới. Showa Women's University Institute of International Culture.

External links

[edit]- Hội An World Cultural Heritage – Hội An Center for Culture and Sports

- Official website Archived 2021-07-28 at the Wayback Machine – Hội An City People's Committee