Draft:Earth and humans

| Submission declined on 9 June 2025 by Bunnypranav (talk). Thank you for your submission, but the subject of this article already exists in Wikipedia. You can find it and improve it at Human instead.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

Comment: This is just a bunch of other articles transcluded here., definitely not fit for its own article. The title is also problematic per jlwoodwa. ~/Bunnypranav:<ping> 05:23, 9 June 2025 (UTC)

Comment: This is just a bunch of other articles transcluded here., definitely not fit for its own article. The title is also problematic per jlwoodwa. ~/Bunnypranav:<ping> 05:23, 9 June 2025 (UTC)

Comment: The title "Earth (people)" means a people named Earth, and doesn't seem to accurately describe the subject of this article. jlwoodwa (talk) 05:16, 9 June 2025 (UTC)

Comment: The title "Earth (people)" means a people named Earth, and doesn't seem to accurately describe the subject of this article. jlwoodwa (talk) 05:16, 9 June 2025 (UTC)

Humans have lived on Earth for around 300,000 years.

History

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Human history or world history is the record of humankind from prehistory to the present. Modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and initially lived as hunter-gatherers. They migrated out of Africa during the Last Ice Age and had spread across Earth's continental land except Antarctica by the end of the Ice Age 12,000 years ago. Soon afterward, the Neolithic Revolution in West Asia brought the first systematic husbandry of plants and animals, and saw many humans transition from a nomadic life to a sedentary existence as farmers in permanent settlements. The growing complexity of human societies necessitated systems of accounting and writing.

These developments paved the way for the emergence of early civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China, marking the beginning of the ancient period in 3500 BCE. These civilizations supported the establishment of regional empires and acted as a fertile ground for the advent of transformative philosophical and religious ideas, initially Hinduism during the late Bronze Age, and – during the Axial Age: Buddhism, Confucianism, Greek philosophy, Jainism, Judaism, Taoism, and Zoroastrianism. The subsequent post-classical period, from about 500 to 1500 CE, witnessed the rise of Islam and the continued spread and consolidation of Christianity while civilization expanded to new parts of the world and trade between societies increased. These developments were accompanied by the rise and decline of major empires, such as the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic caliphates, the Mongol Empire, and various Chinese dynasties. This period's invention of gunpowder and of the printing press greatly affected subsequent history.

During the early modern period, spanning from approximately 1500 to 1800 CE, European powers explored and colonized regions worldwide, intensifying cultural and economic exchange. This era saw substantial intellectual, cultural, and technological advances in Europe driven by the Renaissance, the Reformation in Germany giving rise to Protestantism, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment. By the 18th century, the accumulation of knowledge and technology had reached a critical mass that brought about the Industrial Revolution, substantial to the Great Divergence, and began the modern period starting around 1800 CE. The rapid growth in productive power further increased international trade and colonization, linking the different civilizations in the process of globalization, and cemented European dominance throughout the 19th century. Over the last quarter-millennium, which included two devastating world wars, there has been a great acceleration in many spheres, including human population, agriculture, industry, commerce, scientific knowledge, technology, communications, military capabilities, and environmental degradation.

The study of human history relies on insights from academic disciplines including history, archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, and genetics. To provide an accessible overview, researchers divide human history by a variety of periodizations.

Demographics

[edit]

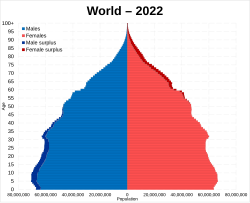

Earth has a human population of over 8.2 billion as of 2025, with an overall population density of 50 people per km2 (130 per sq. mile). Nearly 60% of the world's population lives in Asia, with more than 2.8 billion in the countries of India and China combined. The percentage shares of China, India and rest of South Asia of the world population have remained at similar levels for the last few thousand years of recorded history.[1][2]

The world's population is predominantly urban and suburban,[3] and there has been significant migration toward cities and urban centers. The urban population jumped from 29% in 1950 to 55.3% in 2018.[4][5] Interpolating from the United Nations prediction that the world will be 51.3% urban by 2010, Ron Wimberley, Libby Morris and Gregory Fulkerson estimated 23 May 2007 would have been the first time the urban population was more populous than the rural population in history.[6] India and China are the most populous countries,[7] as the birth rate has consistently dropped in wealthy countries and until recently remained high in poorer countries. Tokyo is the largest urban agglomeration in the world.[5]

As of 2024, the total fertility rate of the world is estimated at 2.25 children per woman,[8] which is slightly below the global average for the replacement fertility rate of approximately 2.33 (as of 2003).[9] However, world population growth is unevenly distributed, with the total fertility rate ranging from the world's lowest of 0.8 in South Korea,[10] to the highest of 6.7 in Niger.[11] The United Nations estimated an annual population increase of 1.14% for the year of 2000.[12] The current world population growth is approximately 1.09%.[5] People under 15 years of age made up over a quarter of the world population (25.18%), and people age 65 and over made up nearly ten percent (9.69%) in 2021.[5] The world's literacy rate has increased dramatically in the last 40 years, from 66.7% in 1979 to 86.3% today.[13] Lower literacy levels are mostly attributable to poverty[14] and are found mostly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.[15]

The world population more than tripled during the 20th century from about 1.65 billion in 1900 to 5.97 billion in 1999.[16][17][18] It reached the 2 billion mark in 1927, the 3 billion mark in 1960, 4 billion in 1974, and 5 billion in 1987.[19] The overall population of the world is approximately 8 billion as of November 2022. Currently, population growth is fastest among low wealth, least developed countries.[20] The UN projects a world population of 9.15 billion in 2050, a 32.7% increase from 6.89 billion in 2010.[16]

Languages

[edit]A world language (sometimes called a global language[21]: 101 or, rarely, an international language[22][23]) is a language that is geographically widespread and makes it possible for members of different language communities to communicate. The term may also be used to refer to constructed international auxiliary languages.

English is the foremost world language and, by some accounts, the only one. Other languages that can be considered world languages include Arabic, French, Russian, and Spanish, although there is no clear academic consensus on the subject. Some writers consider Latin to have formerly been a world language.

Religions

[edit]

World religions is a socially-constructed category used in the study of religion to demarcate religions that are deemed to have been especially large, internationally widespread, or influential in the development of human societies. It typically consists of the "Big Five" religions: Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. These are often juxtaposed against other categories, such as folk religions, Indigenous religions, and new religious movements (NRMs), which are also used by scholars in this field of research.

The "World Religions paradigm" was developed in the United Kingdom during the 1960s, where it was pioneered by phenomenological scholars of religion such as Ninian Smart. It was designed to broaden the study of religion away from its heavy focus on Christianity by taking into account other large religious traditions around the world. The paradigm is often used by lecturers instructing undergraduate students in the study of religion and is also the framework used by school teachers in the United Kingdom and other countries. The paradigm's emphasis on viewing these religious movements as distinct and mutually exclusive entities has also had a wider impact on the categorisation of religion—for instance in censuses—in both Western countries and elsewhere.

Since the late 20th century, the paradigm has faced critique by scholars of religion, such as Jonathan Z. Smith, some of whom have argued for its abandonment. Critics have argued that the world religions paradigm is inappropriate because it takes the Protestant branch of Nicene Christianity as the model for what constitutes "religion"; that it is tied up with discourses of modernity, including the power relations present in modern society; that it encourages an uncritical understanding of religion; and that it makes a value judgment as to what religions should be considered "major". Others have argued that it remains useful in the classroom, so long as students are made aware that it is a socially-constructed category.

Education

[edit]Geography

[edit]

Human geography or anthropogeography is the branch of geography which studies spatial relationships between human communities, cultures, economies, and their interactions with the environment, examples of which include urban sprawl and urban redevelopment.[24] It analyzes spatial interdependencies between social interactions and the environment through qualitative and quantitative methods.[25][26] This multidisciplinary approach draws from sociology, anthropology, economics, and environmental science, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the intricate connections that shape lived spaces.[27]

Climate change

[edit]

The effects of climate change on human health are profound because they increase heat-related illnesses and deaths, respiratory diseases, and the spread of infectious diseases. There is widespread agreement among researchers, health professionals and organizations that climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century.[28][29]

Rising temperatures and changes in weather patterns are increasing the severity of heat waves, extreme weather and other causes of illness, injury or death. Heat waves and extreme weather events have a big impact on health both directly and indirectly. When people are exposed to higher temperatures for longer time periods they might experience heat illness and heat-related death.[30]

In addition to direct impacts, climate change and extreme weather events cause changes in the biosphere.[31][32] Certain diseases that are carried and spread by living hosts such as mosquitoes and ticks (known as vectors) may become more common in some regions. Affected diseases include dengue fever and malaria.[30] Contracting waterborne diseases such as diarrhoeal disease will also be more likely.[33]

Changes in climate can cause decreasing yields for some crops and regions, resulting in higher food prices, less available food, and undernutrition. Climate change can also reduce access to clean and safe water supply. Extreme weather and its health impact can also threaten the livelihoods and economic stability of people. These factors together can lead to increasing poverty, human migration, violent conflict, and mental health issues.[34][35]

Climate change affects human health at all ages, from infancy through adolescence, adulthood and old age.[30] Factors such as age, gender and socioeconomic status influence to what extent these effects become wide-spread risks to human health.[36]: 1867 Some groups are more vulnerable than others to the health effects of climate change. These include children, the elderly, outdoor workers and disadvantaged people.[30]: 15

Governance and politics

[edit]

The United Nations, a non-sovereign entity, is the main global intergovernmental organization.[37]

Economy

[edit]This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (May 2025) |

| World economy |

|---|

|

The world economy or global economy is the economy of all humans in the world, referring to the global economic system, which includes all economic activities conducted both within and between nations, including production, consumption, economic management, work in general, financial transactions and trade of goods and services.[38][39] In some contexts, the two terms are distinct: the "international" or "global economy" is measured separately and distinguished from national economies, while the "world economy" is simply an aggregate of the separate countries' measurements. Beyond the minimum standard concerning value in production, use and exchange, the definitions, representations, models and valuations of the world economy vary widely. It is inseparable from the geography and ecology of planet Earth.

It is common to limit questions of the world economy exclusively to human economic activity, and the world economy is typically judged in monetary terms, even in cases in which there is no efficient market to help valuate certain goods or services, or in cases in which a lack of independent research, genuine data or government cooperation makes calculating figures difficult. Typical examples are illegal drugs and other black market goods, which by any standard are a part of the world economy, but for which there is, by definition, no legal market of any kind.

However, even in cases in which there is a clear and efficient market to establish monetary value, economists do not typically use the current or official exchange rate to translate the monetary units of this market into a single unit for the world economy since exchange rates typically do not closely reflect worldwide value – for example, in cases where the volume or price of transactions is closely regulated by the government.

Rather, market valuations in a local currency are typically translated to a single monetary unit using the idea of purchasing power. This is the method used below, which is used for estimating worldwide economic activity in terms of real United States dollars or euros. However, the world economy can be evaluated and expressed in many more ways. It is unclear, for example, how many of the world's 7.8 billion people (as of March 2020[update])[40][41] have most of their economic activity reflected in these valuations.

Until the middle of the 19th century, global output was dominated by China and India. Waves of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe and Northern America shifted the shares to the Western Hemisphere. As of 2025, the following 21 countries or collectives have reached an economy of at least US$2 trillion by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in nominal or Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms: Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Poland, South Korea, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, the European Union and the African Union.[42][43]

Between 1820 and 2000, global income inequality increased with almost 50%. However, this change occurred mostly before 1950. Afterwards, the level of inequality remained mostly stable. It is important to differentiate between between-country inequality, which was the driving force for this pattern, and within country inequality, which remained largely constant.[44] Global income inequality peaked approximately in the 1970s, when world income was distributed bimodally into "rich" and "poor" countries with little overlap. Since then, inequality has been rapidly decreasing, and this trend seems to be accelerating. Income distribution is now unimodal, with most people living in middle-income countries.[45]

As of 2000[update], a study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research at United Nations University found that the richest 1% of adults owned 40% of global assets, and that the richest 10% of adults accounted for 85% of the world total. The bottom half of the world adult population owned barely 1% of global wealth. Oxfam International reported that the richest 1 percent of people owned 48 percent of global wealth As of 2013[update],[46] and would own more than half of global wealth by 2016.[47] In 2014, Oxfam reported that the 85 wealthiest individuals in the world had a combined wealth equal to that of the bottom half of the world's population, or about 3.5 billion people.[48][49][50][51][52]

Despite high levels of government investment, the global economy decreased by 3.4% in 2020 in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic,[53] an improvement from the World Bank's initial prediction of a 5.2 percent decrease.[54] Cities account for 80% of global GDP, thus they faced the brunt of this decline.[55][56] The world economy increased again in 2021 with an estimated 5.5 percent rebound.[57]

Technology

[edit]

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques by humans. Technology includes methods ranging from simple stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and information technology that has emerged since the 1980s. The term technology comes from the Greek word techne, meaning art and craft, and the word logos, meaning word and speech. It was first used to describe applied arts, but it is now used to describe advancements and changes that affect the environment around us.[58]

New knowledge has enabled people to create new tools, and conversely, many scientific endeavors are made possible by new technologies, for example scientific instruments which allow us to study nature in more detail than our natural senses.

Since much of technology is applied science, technical history is connected to the history of science. Since technology uses resources, technical history is tightly connected to economic history. From those resources, technology produces other resources, including technological artifacts used in everyday life. Technological change affects, and is affected by, a society's cultural traditions. It is a force for economic growth and a means to develop and project economic, political, military power and wealth.

Culture

[edit]Sport

[edit]

The history of sports extends back to the Ancient world in 7000 BC. The physical activity that developed into sports had early links with warfare and entertainment.[59]

Study of the history of sport can teach lessons about social changes and about the nature of sport itself, as sport seems involved in the development of basic human skills (compare play).[citation needed] As one delves further back in history, dwindling evidence makes theories of the origins and purposes of sport more and more difficult to support.

As far back as the beginnings of sport, it was related to military training. For example, competition was used as a mean to determine whether individuals were fit and useful for service.[citation needed] Team sports were used to train and to prove the capability to fight in the military and also to work together as a team (military unit).[60]

References

[edit]- ^ "China's Population 1.4 billion 2020". ABC News.

- ^ "India Population 1.38 billion UN Data Estimate".

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2018-06-13). "Urbanization". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Urban population (% of total population) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d CIA.gov World Factbook – World Statistics

- ^ World Population Becomes More Urban That Rural

- ^ "Country Comparison :: Population". U.S. Census Bureau. 2008. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ "World Population Prospects: Data Portal – Population Division". United Nations.

- ^ Espenshade TJ, Guzman JC, Westoff CF (2003). "The surprising global variation in replacement fertility". Population Research and Policy Review. 22 (5/6): 575. doi:10.1023/B:POPU.0000020882.29684.8e. S2CID 10798893., Introduction and Table 1, p. 580

- ^ "Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - Korea, Rep". World Bank.

- ^ "Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - Niger". World Bank.

- ^ "Census.gov". Census.gov. 7 January 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Blanchard, Maren⁴ (May 7, 2024). "The Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Literacy: How Literacy is Influenced by and Influences SES". University of Michigan Journal of Economics. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

- ^ "Illiteracy rates by world region 2016". Statista. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ a b World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision Population Database Archived 7 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The World at". Un.org. 12 October 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Population Growth over Human History". Globalchange.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ World Population Milestones

- ^ "United Nations Population Fund". UNFPA. 13 May 1968. Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich (2010). "World Languages: Trends and Futures". In Coupland, Nikolas (ed.). The Handbook of Language and Globalization. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 101–122. doi:10.1002/9781444324068.ch4. ISBN 978-1-4443-2406-8.

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich (1997), Stevenson, Patrick (ed.), "To What Extent is German an International Language?", The German Language and the Real World: Sociolinguistic, Cultural, and Pragmatic Perspectives on Contemporary German, Clarendon Press, pp. 25–53, ISBN 978-0-19-823738-9

- ^ de Mejía, Anne-Marie (2002). Power, Prestige, and Bilingualism: International Perspectives on Elite Bilingual Education. Multilingual Matters. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-1-85359-590-5.

'international language' or 'world language' [...] The following languages of wider communication, that may be used as first or as second or foreign languages, are generally recognised: English, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Arabic, Russian and Chinese.

- ^ Johnston, Ron (2000). "Human Geography". In Johnston, Ron; Gregory, Derek; Pratt, Geraldine; et al. (eds.). The Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 353–360.

- ^ Russel, Polly. "Human Geography". British Library. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Reinhold, Dennie (7 February 2017). "Human Geography". www.geog.uni-heidelberg.de. Archived from the original on 23 September 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Rubenstein, James M. (2020). Cultural Landscape, The: An Introduction to Human Geography (13th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 9780135729625.

- ^ Atwoli, Lukoye; Baqui, Abdullah H; Benfield, Thomas; Bosurgi, Raffaella; Godlee, Fiona; Hancocks, Stephen; Horton, Richard; Laybourn-Langton, Laurie; Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Norman, Ian; Patrick, Kirsten; Praities, Nigel; Olde Rikkert, Marcel G M; Rubin, Eric J; Sahni, Peush (2021-09-04). "Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health". The Lancet. 398 (10304): 939–941. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01915-2. PMC 8428481. PMID 34496267.

- ^ "WHO calls for urgent action to protect health from climate change – Sign the call". World Health Organization. 2015. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ a b c d Romanello, Marina; McGushin, Alice; Di Napoli, Claudia; Drummond, Paul; Hughes, Nick; Jamart, Louis; et al. (October 2021). "The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future" (PDF). The Lancet. 398 (10311): 1619–1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6. hdl:10278/3746207. PMC 7616807. PMID 34687662. S2CID 239046862.

- ^ Baker, Rachel E.; Mahmud, Ayesha S.; Miller, Ian F.; Rajeev, Malavika; Rasambainarivo, Fidisoa; Rice, Benjamin L.; et al. (April 2022). "Infectious disease in an era of global change". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 20 (4): 193–205. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00639-z. ISSN 1740-1534. PMC 8513385. PMID 34646006.

- ^ Wilson, Mary E. (2010). "Geography of infectious diseases". Infectious Diseases: 1055–1064. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-04579-7.00101-5. ISBN 978-0-323-04579-7. PMC 7152081.

- ^ Levy, Karen; Smith, Shanon M.; Carlton, Elizabeth J. (2018). "Climate Change Impacts on Waterborne Diseases: Moving Toward Designing Interventions". Current Environmental Health Reports. 5 (2): 272–282. Bibcode:2018CEHR....5..272L. doi:10.1007/s40572-018-0199-7. ISSN 2196-5412. PMC 6119235. PMID 29721700.

- ^ Watts, Nick; Amann, Markus; Arnell, Nigel; Ayeb-Karlsson, Sonja; Belesova, Kristine; Boykoff, Maxwell; et al. (16 November 2019). "The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate" (PDF). The Lancet. 394 (10211): 1836–1878. Bibcode:2019Lanc..394.1836W. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6. hdl:10044/1/75356. PMC 7616843. PMID 31733928. S2CID 207976337.

- ^ Romanello, Marina; McGushin, Alice; Di Napoli, Claudia; Drummond, Paul; Hughes, Nick; Jamart, Louis; et al. (October 2021). "The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future" (PDF). The Lancet. 398 (10311): 1619–1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6. hdl:10278/3746207. PMC 7616807. PMID 34687662. S2CID 239046862.

- ^ Watts, Nick; Adger, W Neil; Agnolucci, Paolo; Blackstock, Jason; Byass, Peter; Cai, Wenjia; et al. (2015). "Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health". The Lancet. 386 (10006): 1861–1914. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6. hdl:10871/17695. PMID 26111439. S2CID 205979317.

- ^ "The Essential UN". www.un.org. Retrieved 2025-06-09.

- ^ "THE GLOBAL ECONOMY | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "World Economy." – Definition. American English Definition of with Pronunciation by Macmillan Dictionary. N.p., n.d. Web. 2 January 2015.

- ^ "World Population: 2020 Overview". Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

- ^ "2020 World Population Data Sheet". Archived from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database April 2025". www.imf.org. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "More QE From the Bank of England to Support the UK Economy in 2021". Vant Age Point Trading. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ van Zanden, Jan Luiten; Baten, Joerg; Földvari, Peter; van Leeuwen, Bas (2011). "The Changing Shape of Global Inequality 1820–2000: Exploring a new dataset". CGEH Working Paper Series.

- ^ "Parametric estimations of the world distribution of income". 22 January 2010.

- ^ Oxfam: Richest 1 percent sees share of global wealth jump

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (19 January 2015). "Richest 1% Likely to Control Half of Global Wealth by 2016, Study Finds". New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Rigged rules mean economic growth increasingly "winner takes all" for rich elites all over world. Oxfam. 20 January 2014.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (20 January 2014). Oxfam: World's Richest 1 Percent Control Half Of Global Wealth. NPR. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Stout, David (20 January 2014). "One Stat to Destroy Your Faith in Humanity: The World's 85 Richest People Own as Much as the 3.5 Billion Poorest". Time. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Wearden, Graeme (20 January 2014). "Oxfam: 85 richest people as wealthy as poorest half of the world". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas (22 July 2014). "An Idiot's Guide to Inequality". New York Times. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ OECD (March 2021). "OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2021". Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "The Global Economic Outlook During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Changed World". World Bank. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Cities are the hub of the global green recovery". blogs.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Mayor of Lima sees COVID-19 as spark for an urban hub to the green recovery". European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ Lucia Quaglietti, Collette Wheeler (11 January 2022). "The Global Economic Outlook in five charts". World Bank. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "history of technology – Summary & Facts". Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Crowther, Nigel B. (2007). Sport in Ancient Times. Praeger Series on the Ancient World. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. xxii. ISBN 9780275987398. ISSN 1932-1406. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

People in the ancient world rarely practiced sports for their own sake, especially in the earliest times, for physical pursuits had strong links with ritual, warfare, entertainment, or other external features.

- ^ "Sport and preparing troops for war". NAM.ac.uk. National Army Museum. Retrieved 17 November 2021.