Cherrydale, Virginia

Cherrydale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 22207 |

| Area code(s) | 703 |

Cherrydale Historic District | |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Lorcom Ln., N. Utah and N. Taylor Sts., and I-66, Arlington County, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 38°53′41″N 77°6′32″W / 38.89472°N 77.10889°W |

| Area | 286.3 acres (115.9 ha) |

| Built | 1898-1953 |

| Architect | Conner, J. Arthur; et al. |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian, Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Late 19th And 20th Century American Movement |

| NRHP reference No. | 03000461 |

| VLR No. | 000-7821 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 22, 2003[2] |

| Designated VLR | March 19, 2003[1] |

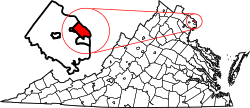

Cherrydale is a neighborhood in northern Arlington, Virginia. Centered around an intersection called Five Points, it is bounded by North Taylor Street, North Utah Street, Interstate 66, Langston Boulevard, North Pollard Street, Vacation Lane, Lorcum Lane, and Military Road.

Originating as a small agricultural community at the intersection of Langston Boulevard and Military Road following the Civil War, Cherrydale grew into a streetcar suburb of Washington, D.C. after the arrival of the Great Falls and Old Dominion Railroad (GF&OD) in the early 1900s. Rapid development occurred through to the 1950s, by which point Cherrydale had an established series of community organizations and a commercial district along Langston Boulevard. During the Civil rights movement, Cherrydale was the site of a sit-in at two local lunch counters that contributed to the desegregation of Arlington County businesses in June 1960. Stratford Junior High School, located on Vacation Lane and now called Dorthy Hamm Middle School, was the first school in the state of Virginia to desegregate in 1959. As one of Arlington's earliest 20th century suburbs that has retained much of its historic architecture, Cherrydale was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 2003. The neighborhood's historic firehouse, built in 1919, was added separately to the Registry in 1995.

History

[edit]18th and 19th centuries

[edit]During the colonial era, present-day Cherrydale was part of two land grants by Thomas Fairfax, 5th Lord Fairfax of Cameron to Thomas Going, who was given 653 acres in 1708, and Reverend James Brechin of St Peter's Church in New Kent County, Virginia, who was given 795 acres in 1716.[3] The former tract was eventually inherited by George Mason, becoming part of the Mason family's landholdings until it was lost by George's son John in the 1830s after his bankruptcy.[4] 516 acres of the latter parcel were sold to the Anglican Fairfax Parish in 1770 as a glebe, on which the original Glebe House was built in 1775.[4] The glebe land was tended by tenant farmers and enslaved labor.[5] Andrew Donaldson began working the land in 1780 and is considered one of Cherrydale's first permanent residents.[4]

By the 19th century, Langston Boulevard, then called the Fairfax and Georgetown Road, and North Quincy Street, then known by various names including Ballston Road, were constructed as thoroughfares connecting agricultural producers to markets in Washington and Alexandria.[4] The Civil War brought a military presence with the Union's construction of the nearby Arlington Line, including Fort Smith and Fort Strong.[6] Military Road was also built during the war in 1861 to connect the Arlington Line and Chain Bridge defenses.[6]

Following the war, former Union soldier Conant C. Nelson, originally from New Jersey, established a general store at the intersection of Military Road and Langston Boulevard in 1869.[7] A small collection of buildings had developed at this intersection by 1879.[8] Local figures, including members of the Donaldson family, and new arrivals such as Francis G. Schutt of New York, continued to farm the land surrounding the intersection throughout the rest of the 19th century. Robert Shreve, who married into the Donaldson family, acquired Nelson's store and built his family home on North Pollard Street, which still stands today.[7] Shreve and his father-in-law, Dorsey Donaldson, established a cherry tree orchard on North Quincy Street in the late 19th century.[7] In 1893, Donaldson and Shreve both applied for the construction of a "Cherrydale" post office; the name may have been inspired by their cherry orchard.[7]

Early 20th century suburbanization

[edit]The completion of Arlington's first courthouse outside of Alexandria in 1898 and the anticipated arrival of rail service motivated Cherrydale's landowners to begin subdividing their holdings for prospective residential development; Francis G. Schutt initiated the first residential subdivision around 1900.[9] The GF&OD Railroad reached Cherrydale in 1904, providing a commuter streetcar service to Rosslyn starting in 1907.[10] The Dominion Heights subdivision, which consisted of 128 lots, was created shortly before this in 1905 by Josephine A. Cunningham, and was mostly developed by 1925.[11] Streetcar stops were built at the Langston Boulevard and Military Road intersection, as well as adjacent to Dominion Heights.[11] A third stop with service to Bluemont and Alexandria, Thrifton Junction, was established at Langston Boulevard and Kirkwood Road after the GF&OD purchased the Bluemont line of the Southern Railway in 1911.[12] This stimulated further development, and by 1926 twenty subdivisions had been created in the Cherrydale area[12]

Public services and community organizations were formed as Cherrydale's population increased, including its volunteer fire department in 1898, the Cherrydale School in 1907, and the Cherrydale Citizens' Association in 1910.[13] The 1920s saw the establishment of 5 churches, the Cherrydale Branch of the Arlington Public Library, fraternal organizations such as the Cherrydale Masonic Lodge, and the Cherrydale Women's Club.[14] Improvements in local roads drove further growth as well as car ownership, which resulted in the eventual closure of Cherrydale's rail service in 1934.[15] While growth slowed throughout Arlington during the Great Depression, the expansion of government personnel during the New Deal era and World War II sparked renewed development; 10 subdivisions were platted in Cherrydale between 1936 and 1946.[15] Cherrydale's commercial district along Langston Boulevard also developed during this period, particularly after the closure of rail service opened up more land.[16]

As a community in the Jim Crow South established during the nadir of American race relations, Cherrydale had an active Ku Klux Klan presence in the early 1920s through the 1960s. 250 Klansmen passed through the neighborhood during a 1922 march from Chain Bridge that preceded their 1926 parade in Washington; the Klan was known to participate in public celebrations into the 1950s.[17] Cherrydale's subdivisions also had racially restrictive covenants that prevented African Americans and other minority groups from purchasing property.[18] Nearby Halls Hill, a segregated black community, was populated in part with former African American residents of Cherrydale.[19]

Cherrydale sit-ins

[edit]During the Civil rights era, the Nonviolent Action Group at Howard University organized a sit-in in Cherrydale.[20] This took place from June 9 to June 10, 1960 at the Peoples Drug and Cherrydale Drug Fair lunch counters, which at the time were not welcome to black customers.[21] Over the 2 days, protesters were refused service by the store managers and endured verbal and physical abuse from local white students of Washington-Lee High School, Stratford Junior High School, and St. Agnes School.[22] Stratford had been the first school in Virginia to desegregate in 1959.[23] Plainclothes members of the Arlington-based American Nazi Party and their leader, George Lincoln Rockwell, staged racist counter protests on both days in favor of segregation and white supremacy, harassed the sit-in participants, and handed out propaganda flyers at nearby schools.[22] Some students and bystanders were sympathetic to the Civil Rights cause and supported the sit-in.[24]

The sit-ins had a heavy media presence[25] and were overseen by local Arlington County police, who issued warnings against Nazi Party members and other agitators.[26] Following the sit-in, the protesters demanded to have mediated sessions with local businesses, residents, and the Arlington County government to push for the desegregation of County stores.[27] The County Board proclaimed that they could not change the policies of private businesses, but urged business owners to voluntarily desegregate.[27] On June 18, the sit-ins resumed at lunch counters in Shirlington.[27] By the end of June 1960, many Arlington stores had rescinded their segregatory policies, and Arlington became the first county in Virginia to desegregate their lunch counters, as well as the first county in the entire South where a restaurant chain served black customers.[27] Business in Fairfax County and Alexandria also ended their segregation policies in response.[27] In 2018, Cherrydale residents commemorated the sit-in and its impact with a bronze plaque at the site of the Cherrydale Drug Fair.[28]

Further developments

[edit]In 1966, the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad closed their freight service along the Rosslyn spur and Bluemont lines, which were acquired by the Virginia Department of Transportation to build Interstate 66.[29] The freeway was completed in 1988; homes in Cherrydale that were formerly adjacent to the railroad tracks were moved or demolished.[29]

Starting in the late 1980s, rising property values encouraged many homeowners in Cherrydale to renovate or demolish historic houses.[29] The county government also planned to redevelop Cherrydale into an urban village as a part of revitalization efforts taking place across Arlington during the 1980s and 1990s.[30] This was expressed in the 1994 Cherrydale Revitalization Plan, which recommended a variety of changes to improve Cherrydale's pedestrian friendliness, particularly along the Langston Boulevard commercial corridor.[31] The 1994 plan has enabled the construction of several apartment buildings and townhouse communities.[32] The County's 2023 Langston Boulevard Area Plan, which envisions communities along the highway becoming higher density, more walkable, and more mixed-use, has thus far excluded Cherrydale given the existence of the 1994 plan.[33][32]

Architecture

[edit]Dwellings from Cherrydale's first series of subdivisions are generally single-family and semi-detached homes built in the center of large lots.[34] Architectural styles from this period include Queen Anne, Italianate, Colonial Revival, Craftsman bungalows, and American Foursquare. Most homes are wood-framed, and many have concrete foundations that were manufactured locally by the Cherrydale Cement Block Company.[35] Bungalow-style kit houses are widely represented, reflecting their popularity that was enabled by Cherrydale's proximity to the W&OD railway.[36] Some homes are more vernacular and were built by locals such as Asa Donaldson of the Donaldson family.[37] Commercial and community structures from Cherrydale's early development include the Colonial Revival Cherrydale Volunteer Fire House (1919), which is listed separately on the National Register of Historic Places, Schutt's Hall (c. 1908-1916), and the Gothic Revival Methodist Society building (c. 1918-1925).[38]

Houses built in the second quarter of the 20th century are mostly in the Colonial Revival style. More modest and smaller-scale than those in other Arlington neighborhoods, many are Cape Cod structures that were intended as more affordable homes for middle and working class residents[39] Also present are several Mission Revival and International Style dwellings.[40] The Masonic Lodge (1936) on Langston Boulevard, which now hosts a hardware store, is one of several examples of commercial buildings from this era, which also consist of car dealerships, gas stations, and auto shops.[41]

Geography

[edit]Cherrydale is centered on the intersection of Langston Boulevard, Military Road, North Quincy Street, and Cherry Hill Road, which is known as Five Points.[42] It is generally bounded North Taylor Street, North Utah Street, Interstate 66, Langston Boulevard, North Pollard Street, Vacation Lane, Lorcum Lane, and Military Road. It is surrounded by the neighborhoods of Waverly Hills, Ballston, Virginia Square, Lyon Village, Maywood, Woodmont, and Donaldson Run.[43] Spout Run flows through Cherrydale and empties into the Potomac River opposite the Three Sisters; it was partially buried during Cherrydale's 20th century development.[44]

Infrastructure

[edit]Cherrydale's main arterial roads consist of Langston Boulevard, a component highway of U.S. Route 29, Military Road, and Interstate 66. The Custis Trail, a shared-use path, runs along Interstate 66.[45]

Public transit

[edit]2 Capital Bikeshare stations are located in Cherrydale on North Woodstock Street and North Monroe Street.[46] The neighborhood is served by the following Metrobus and Arlington Transit bus routes:[47][48]

- Metrobus 3Y: E Falls Church-McPherson Sq

- ART 55: Rosslyn-East Falls Church

- ART 56: Military Rd-Rosslyn Metro

Arts and culture

[edit]Cherrydale has a weekly farmer's market at Dorthy Hamm Middle School open between April and November on Saturdays.[49] The Cherrydale Branch of the Arlington Public Library is located on Military Road[50]

Parks and recreation

[edit]Cherrydale has 4 small to medium-sized parks that have playgrounds, nature trails, and green space. They include:

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Cherrydale Historic District". dhr.virginia.gov. Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved May 27, 2025.

- ^ "National Register Database and Research". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved May 27, 2025.

- ^ Albee p. 146

- ^ a b c d Albee p. 147

- ^ "Glebe House". enslavedarl.org. Arlington Historical Society. Retrieved May 30, 2025.

- ^ a b Albee p. 148

- ^ a b c d Albee p. 149

- ^ Albee p. 150

- ^ Albee pp. 150-151

- ^ Albee p. 151

- ^ a b Albee p. 152

- ^ a b Albee p. 153

- ^ Albee p. 156-157

- ^ Albee p. 157-159

- ^ a b Albee p. 160

- ^ Albee p. 162

- ^ Embree pp.127-128

- ^ "Racial Covenants in Northern Virginia". documentingexclusion.org. Documenting Exclusion and Resilience Project. Retrieved May 28, 2025.

- ^ Embree p. 127

- ^ Embree p. 126

- ^ Embree pp. 129-130

- ^ a b Embree p. 132

- ^ Embree p. 127

- ^ Embree p. 139

- ^ Embree p. 138

- ^ Embree p. 140

- ^ a b c d e Embree p. 143

- ^ Embree p. 144

- ^ a b c Albee p. 163

- ^ Hong, Peter Y. (June 2, 1994). "Cherrydale Fears New Highway Lane". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2025.

- ^ Lee Highway Cherrydale Revitalization Plan (PDF). Arlington County Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development, Planning Division. June 7, 1994. p. 9. Retrieved May 28, 2025.

- ^ a b DeVoe, Joe (December 7, 2023). "A collection of single-family homes in Cherrydale will soon be eligible for Missing Middle redevelopment". ArlNow. Retrieved May 28, 2025.

- ^ DeVoe, Joe (May 18, 2023). "Langston Blvd planning effort elicits strong opinions from residents about the future of their neighborhoods". ArlNow. Retrieved May 28, 2025.

- ^ Albee p. 8

- ^ Albee p. 7

- ^ Albee p. 12

- ^ Albee p. 149

- ^ Albee p. 16

- ^ Albee p. 13

- ^ Albee p. 14

- ^ Albee p. 18

- ^ "Cherrydale". arlingtonva.us. County of Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Arlington County Civic Associations map" (PDF). clarendoncourthouseva.org. Arlington County GIS Map. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ Albree p. 150

- ^ "Cherrydale" (PDF). bikearlington.com. Arlington County Commuter Services. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "System Map". capitalbikeshare.com. Capital Bikeshare. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "WMATA System Bus Map" (PDF). wmata.com. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "ART System Map". arlingtontransit.com. Arlington County Commuter Services. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Cherrydale Farmer's Market". langstonblvdalliance.com. Langston Boulevard Alliance. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Cherrydale Library". library.arlingtonva.us. Arlington Public Library. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Cherrydale Park". arlingtonva.us. County of Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Cherrydale Fire Station Park". arlingtonva.us. County of Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Oak Grove Park". arlingtonva.us. County of Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Cherry Valley Park". arlingtonva.us. County of Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Albee, Carrie E.; Trieschmann, Laura V. (November 2002). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Cherrydale (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- Embree, Gregory J. (2022). "The Cherrydale Drug Fair Sit-In, 9–10 June 1960: An Arlington Neighborhood's Brush with History". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 130 (2): 124–150. Retrieved May 29, 2025.