Atlanta Compromise

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

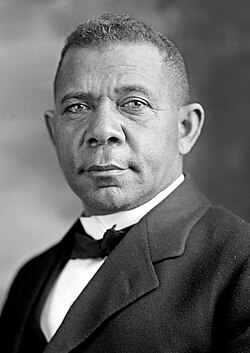

The Atlanta Compromise (historically called accommodationism) was a proposal put forth in 1895 by prominent African American leader Booker T. Washington. His proposal called for Southern blacks to accept segregation and to temporarily refrain from campaigning for equal rights, including the right to vote. In return, he advocated that blacks would receive basic legal protections, access to property ownership, employment opportunities, and vocational and industrial education.

The proposal met with opposition from other black leaders, most notably W. E. B. Du Bois, who rejected the compromise's emphasis on accommodation and limited political ambition. Du Bois and others instead advocated for full civil rights and the immediate end of segregation. From 1903 until Washington's death in 1915, the two figures engaged in an extended public debate over the direction of African American advancement.

The Compromise was the dominant policy pursued by black leaders in the South from 1895 to 1915. However, it did not end segregation, nor produce equal rights for Southern blacks. Those goals were not significantly advanced until the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Background

[edit]The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War, changed the legal status of slaves living in the Confederate States from enslaved to free. The institution of slavery was abolished nationwide with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.[1][2][a] During the Reconstruction era (from about 1865 until 1877), the federal government enacted many progressive laws in the South. These measures aimed to eliminate legal segregation and extend civil and political rights to former slaves. Southern blacks gained the right to vote and became able to hold public office at local, state, and national levels.[4]

Booker T. Washington was born into slavery in 1856 in West Virginia. After attending Hampton Institute for a few years, Washington became president of the newly formed Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in 1881.[5] Living in the South during the Reconstruction era, Washington knew that many white Southerners viewed Reconstruction as an occupation by foreigners: they saw their government and society being unfairly commandeered by Northern whites and Southern blacks.[6]

Beginning around 1877, the progress made during the Reconstruction era was reversed as white Southerners gained more political power at both the state and federal levels.[7] Through the Democratic Party, anti-black Southern whites used their new dominance to embark on an aggressive campaign to reshape their government and exclude blacks from white society.[6][7] Between 1877 and 1908, Southern states enacted laws that institutionalized racial segregation and effectively prevented black citizens from voting or holding public office.[4][7][8]

Acutely aware of the diminishing influence of blacks in the South, Washington felt it was useless for Southern blacks to protest for political power; at best, they could only hope to stop the downward spiral of white domination.[9] In 1884, Washington gave a speech to a national educational conference. In it, he proposed concepts that he would later use in his 1895 Atlanta Compromise address: Washington suggested that blacks should turn inward and emphasize solidarity, work, and self-help – and reject political activism.[10][11] According to historian Louis R. Harlan, Washington had concluded that "the Reconstruction experiment in racial democracy failed because it began at the wrong end, emphasizing political means and civil rights acts rather than economic means and self-determination."[12][13]

African American leader Frederick Douglass died in February 1895, leaving a power vacuum in the black community that Washington stepped into.[14][15] One of Washington's first major acts after Douglass' death was delivering the Atlanta Exposition Speech.[14] Until he died in 1915, Washington and his allies – collectively known as the "Tuskegee Machine" – dominated the African American press, political appointments, and relations with white philanthropists.[14][15]

The Compromise

[edit]Washington's 1895 speech

[edit]

The Atlanta Compromise originated in a speech delivered by Washington to the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 18, 1895.[7][b] Black involvement in the Exposition began in early 1895, when white business leaders from Georgia invited Washington to assist in delivering a presentation to a U.S. Congressional committee, seeking federal support for the event.[7] The white members of the delegation were impressed with Washington's address to the committee and invited him to speak at the exposition when it was held later that year.[7][17]

The master of ceremonies of the Cotton Exposition was former governor of Georgia Rufus Bullock, who introduced Washington by saying: "We have with us today a representative of Negro enterprise and Negro civilization."[18] The address was delivered to a segregated audience of blacks and whites, and was delivered in less than ten minutes.[7][19]

Washington summarized his proposal near the end of the address:

"The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house."[20]

Upon the speech's conclusion, the whites in the audience gave Washington a standing ovation.[17][c] Clark Howell, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, stood on the stage and proclaimed the speech to be "the beginning of a moral revolution in America."[17] Washington was congratulated by many white leaders present in the audience, including former governor Bullock.[22] The text of the speech was distributed to most major US newspapers via telegraph.[17] A few days after the speech, Washington received a letter of congratulations from President Grover Cleveland.[16] Washington and his proposal received praise from several major white-owned newspapers in the days following the speech.[23]

Washington did not use the phrase "Atlanta Compromise" to describe his proposal. That phrase was coined by Du Bois eight years after the address in his 1903 essay "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others", which was published in his book The Souls of Black Folk.[24][25][d]

Elements of the Compromise

[edit]

The Atlanta Compromise was Washington's solution to what was then called "the Negro problem": a phrase used to refer to the dismal economic and social conditions of blacks, and the tense relationship between blacks and whites in the post-Reconstruction South.[17][26] The essence of the Compromise was a bargain: blacks would remain peaceful, tolerate segregation, refrain from demanding equal rights or holding political office, avoid college education, and provide a dependable workforce for Southern industry and agriculture.[27][28] In return, Washington hoped that whites would offer job opportunities, permit blacks to own property and homes, build schools for children, and create vocational institutes to give blacks the skills needed in the Southern economy.[17][29][28][e]

Washington's speech appealed to the white businessmen in the audience because it promised them a cooperative, peaceful, reliable workforce; particularly in the areas of industry, agriculture, business, and housekeeping.[17][30] Addressing blacks, Washington encouraged them to focus on manual labor, and accept it as their fate for the near future, claiming that "No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin and not the top."[31] Washington also urged Southern blacks to remain in their home states and avoid the temptation to move to Northern states, repeatedly emphasizing the phrase "Cast down your bucket where you are."[32][33]

The Compromise promoted the construction or expansion of vocational schools (following the model of existing schools such as Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute) to produce nurses, teamsters, farmers, housekeepers, factory workers, repairmen, teachers, cooks, and other tradespeople that would support Southern agriculture and industry.[34][f] The emphasis on industrial education came at the expense of the construction of new liberal-arts universities for Southern blacks: Southern whites were concerned that blacks with a liberal-arts education would be unwilling to work in jobs that required manual labor.[36][37][38] Washington counted on white philanthropists to fund new schools for blacks.[7][39] Washington's speech specifically applauded the Northern philanthropists who had provided funding for black schools during the Reconstruction era: "... the constant help that has come to our educational life not only from the Southern States, but especially from Northern philanthropists who have made their gifts a constant stream of blessing and encouragement."[20]

The Atlanta Compromise accepted racial segregation across most aspects of life, including transportation, education, recreation, and social interaction; whites would have to associate with blacks only when necessary for work or commerce.[40][41] Washington employed a simile to describe his acceptance of segregation: "In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress."[7][17][42]

Washington did not entirely reject civil rights and racial equality.[43] Rather, he viewed them as long-term results that would be obtained only after blacks had demonstrated their worth through loyal, dedicated work within the Southern economy.[31][33][43]

Reception by African Americans

[edit]

After Washington proposed the Atlanta Compromise in 1895, he emerged as the preeminent leader of the African American community.[14][15][44] Many of Washington's associates supported the Compromise, including Robert Moton, who would become the leader of the Tuskegee Institute upon Washington's death.[45] The Compromise was also supported by many middle-class Southern blacks, especially teachers.[46]

However, many Northern intellectuals disagreed with the Compromise, and felt that protest was a more effective solution to racism.[47][46] One of the first recorded criticisms was published in December 1895 – just a few months after the speech – in a letter to the editor of The Christian Recorder newspaper: "What the Negro desires today is a Moses who will not lead him to the plow, for he knows the way there, but who will lead him to the point in this country where he can get all his manhood rights under the Constitution."[48]

Some of the first African American leaders to oppose the Compromise were members of the American Negro Academy, which in the late 1890s fought against segregation. The Academy raised objections to the 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which legalized segregation by endorsing the "separate but equal" doctrine.[49] Around 1900, additional leaders within the black community began voicing opposition to the Atlanta Compromise by challenging racist government policies and advocating for equality for blacks.[50] Opponents included Northern intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois, then a professor at Atlanta University; newspaper editor William Calvin Chase; and William Monroe Trotter, a Boston activist who in 1901 founded the Boston Guardian newspaper as a platform for radical activism.[46][51][52][53] Trotter lived in New England, and in 1899, he observed that conditions in the South were growing worse and that Southern-style racism was creeping into the Northern states.[54]

In 1902 and 1903, black advocates for equal rights fought to gain a larger voice in the conventions of the National Afro-American Council, but they were marginalized because the conventions were dominated by Washington supporters (also known as Bookerites).[55] In July 1903, African American lawyer Edward H. Morris bitterly accused Washington of being responsible for the increasing racism directed against blacks.[56] In the same month, Trotter orchestrated a confrontation with Washington in Boston, a stronghold of activism. This resulted in a minor melee with fistfights and the arrest of Trotter and others.[57][58] The event generated headlines nationwide.[58]

Criticism from W. E. B. Du Bois

[edit]Harvard-educated W. E. B. Du Bois was born and raised in New England and was twelve years younger than Washington. Where Washington was representative of rural, Southern blacks, Du Bois characterized urban, intellectual, Northern blacks.[59][60] Northern blacks had relatively more freedom than those in the South, and were more willing to fight for equal rights. Some Northern blacks felt that the Atlanta Compromise was effectively imposed on Southern blacks by white Southerners.[59][60][g]

Although Du Bois initially supported the Atlanta Compromise,[61][62] over time he came to strongly disagree with Washington's approach.[7][63] The rift between the two men began to develop in 1898 when Washington resigned from the board of Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute, which was governed by a friend of Du Bois.[64][h] In 1900, Du Bois proposed the creation of a national organization of black businessmen, but Washington quickly plagiarized the idea and created the National Negro Business League.[66] In 1901, Du Bois included a negative assessment of the Atlanta Compromise in his review of Washington's autobiography Up From Slavery.[67][68][i]

In 1903 Du Bois harshly criticized the Atlanta Compromise in his influential book, The Souls of Black Folk, which included the statement: "Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission... [His] programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races."[67][69][70] The same year, Du Bois criticized the Atlanta Compromise's plan to build vocational job-training schools instead of universities, writing: "[the] object of all true education is not to make men carpenters; it is to make carpenters men."[33][71][72]

In 1904, Du Bois and Washington – each accompanied by a team of supporters – met in New York in an attempt to defuse tensions between the two factions.[73][j] The summit was not successful: although they agreed to create a "Committee of Twelve" to coordinate future efforts, the committee fell apart within a year.[75][k] In early 1905, Du Bois wrote an article in The Voice of the Negro periodical, which asserted that Washington was effectively bribing the African American press to provide positive reporting on Washington's programs.[77][78] Washington and his allies disputed Du Bois' allegations.[77]

Historian Mark Bauerlein concluded that 1905 marked the end of any collaboration between the two leaders, writing: "[From Du Bois' perspective] Washington controlled the black press, bought loyalty, planted spies, ostracized critics, and co-opted reform movements and let them die. His accommodation of whites had become too obsequious, but more important, his black power had become oppressive."[79]

Results and aftermath

[edit]Under the leadership of Washington's Tuskegee Machine, the Atlanta Compromise was the dominant policy pursued by black leaders in the South from 1895 to 1915.[80][81] During those years, Washington improved the educational infrastructure for blacks, with a focus on vocational schools and schools for children.[7] Most funding came from Northern white philanthropists who provided money for thousands of schools, covering the cost of constructing buildings and paying salaries of teachers.[82][7][39] These philanthropies included the Rosenwald Fund, the Slater Fund, the Peabody Fund, the General Education Board, and the Negro Rural School Fund.[83][84] However, the emphasis on vocational schools meant that fewer liberal-arts colleges or scientific institutes were built, resulting in reduced opportunities for blacks to prepare for careers in law, medicine, art, history, literature, or pure sciences.[37][38]

After Washington introduced the Atlanta Compromise in his 1895 speech, Southern states continued to aggressively adopt Jim Crow laws which formalized segregation in nearly all walks of life.[85][86] Southern states prevented blacks from voting through constitutional amendments and other laws that raised barriers to voter registration. These obstacles included poll taxes, residency and record-keeping requirements, subjective literacy tests, and other devices.[8] Many blacks blamed Washington's policies for the steady degradation of civil rights.[87]

Violence against blacks continued after the Atlanta Compromise. Although the number of lynchings gradually declined after a peak in 1892, over fifty blacks were lynched per year until 1922 (except 1907, 1914, and 1917 had fewer than fifty); and lynchings continued into the 1940s.[88][89][90] Race riots in dozens of cities spanned several decades, killing hundreds of blacks,[90] including in Atlanta (1906), Illinois (1908), East St. Louis (1917), during the Red Summer (1919), and in Tulsa (1921).[91] The 1906 massacre in Atlanta was notable because Washington's speech was presented there only eleven years earlier.[92][l] Du Bois believed that the massacre was partially the result of the Atlanta Compromise.[92][94]

In 1905 – ten years after Washington's speech – Trotter, Du Bois, and other advocates for full and equal rights formed the Niagara Movement to channel their efforts. The movement's "Declaration of Principles" emphatically rejected the Atlanta Compromise and urged African Americans to fight for civil rights.[95][96][97] Although the Niagara Movement dissolved after two years, it served as the forerunner to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), formed in 1909 by Du Bois and others.[98] Several of the co-founders of the NAACP were liberal whites who were beginning to realize that the Atlanta Compromise would not provide civil rights or full equality for African Americans.[99] After the founding of the NAACP, the schism between Washington's Atlanta Compromise and Du Bois' advocacy for full equality became pronounced and public.[99] The NAACP was well-funded, its leadership contained many powerful white Northerners, and it siphoned support away from the Tuskegee Machine.[100]

Another blow to the Tuskegee Machine was the election of President Woodrow Wilson in 1912.[100] Wilson was the first Democratic party president since the Atlanta Compromise speech. Monroe Trotter and other black leaders met with Wilson and pleaded with him to help them combat Jim Crow laws and segregation, but Wilson refused.[101] During Wilson's two terms in office, he reversed many of the gains that African Americans had seen during the Reconstruction era: he replaced many black federal appointees with whites, and he increased racial segregation in the federal workforce.[100][101]

Beginning around 1910 – contrary to the advice offered by Washington in his speech – millions of African Americans began migrating northward, relocating to major urban centers such as New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Washington DC.[102][103] In 1917, black leaders from the Tuskegee Institute pleaded with Southern blacks to remain in the south, leading Du Bois to respond "any ... Negro leadership today that devotes ten times as much space [in their report] to the advantages of living in the South as it gives to lynching and lawlessness is inexcusably blind."[104][m]

After Washington died in 1915, his Tuskegee Machine collapsed, and organized support for the Atlanta Compromise faded.[105][106][107] The Atlanta Compromise failed to achieve its long-term goals of ending segregation or providing equal rights for blacks.[86][92][108] In the decades following Washington's death, campaigns to end legally-sanctioned segregation and achieve equal rights gained momentum, finally achieving success during the civil rights movement with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968.[109]

Retrospective assessment

[edit]Historians continue to debate the effectiveness of Washington's compromise as a strategy for advancing racial equality. In the first half of the 20th century, opinion was shaped by the views of Du Bois, a sociologist who maintained that direct protest was a more effective path to equality than accommodation.[110][111][112][113] However, historians in the latter half of the century were more sympathetic to Washington, arguing that the pervasive racism of the South and the overwhelming political and economic dominance of white society left him with no alternative.[114][115][116] The historian Robert Norrell contended that meaningful progress toward equality was unattainable – regardless of the strategies employed by black leaders – until anti-black stereotypes were removed from mass media, a change that did not begin until after World War II.[117]

Scholars have analyzed Washington's character to determine whether his advocacy for accommodation reflected a genuine personal conviction or – conversely – was a tactical response to the sociopolitical constraints of his time.[108] Some scholars suggest that Washington's emphasis on appeasement served his own interests, as it helped solidify his status as the preeminent African American leader of the era.[118] However, mid-20th-century research uncovered evidence that Washington engaged in quiet efforts to combat racial injustice, including the discreet funding of legal challenges to disenfranchisement, jury exclusion, and peonage.[74][110][119] The secrecy contributed to his early reputation as an appeaser of whites.[11][120][121] Norrell contends that Washington has been unfairly criticized by some African American historians who favored leaders that endorsed confrontation – such as Frederick Douglass or Du Bois – and dismissed leaders who relied on subtlety – such as Washington.[114][n]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ In addition to the Thirteenth Amendment, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were part of a set of federal actions that brought about the end of slavery.[3]

- ^ The exposition is sometimes referred to as the "Atlanta Exposition."[16]

- ^ The Atlanta Constitution newspaper later wrote: "...tears ran down the face of many blacks in the audience. White Southern women pulled flowers from the bosoms of their dresses and rained them on the black man on stage."[21]

- ^ Du Bois wrote: "This group of men honor Mr. Washington for his attitude of conciliation toward the white South; they accept the 'Atlanta Compromise' in its broadest interpretation...."[24]

- ^ The Atlanta Compromise was informal and unwritten. Washington published the transcript of his speech, but there was no subsequent written agreement or contract.

- ^ Momentum to build vocational schools – for both blacks and whites – was well underway before the 1895 speech. Since around 1870, such schools were becoming more popular throughout the country.[35]

- ^ Historian Jack Pole wrote of the conflict between Du Bois and Washington: "... the claim that Du Bois challenged was that of leadership for the Negroes throughout the United States. To judge all aspects of the Negro situation from the Southern angle of vision, and to advocate the policy of accommodation, which may have been the code of survival in the South, as the highest aim of the blacks as a whole, was to cripple Negro claims to advancement precisely where they could be most ambitious and effective. New York State passed an anti-discrimination law in I890 when Southern states were passing segregation laws. It is not to be wondered at that Northern blacks who had fought to establish their position should have murmured against being 'led', and authoritatively spoken for, by a Southern accommodationist imposed on them primarily by Southern whites."[59]

- ^ Aiello lists various dates and events that have been suggested as the start of the rift between Washington and Du Bois.[65]

- ^ Du Bois wrote of Washington: "Among the Negroes, Mr. Washington is still far from a popular leader. Educated and thoughtful Negroes everywhere are glad to honor him and aid him, but all cannot agree with him. He represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment to environment, emphasizing the economic phase; but the two other strong currents of feeling, descended from the past, still oppose him... While these men respect the Hampton-Tuskegee idea [that is, the Atlanta Compromise] to a degree, they believe it falls far short of a complete program. They believe, therefore, also in the higher education of Fisk and Atlanta Universities; they believe in self-assertion and ambition; and they believe in the right of suffrage for blacks on the same terms with whites."[68]

- ^ Historian Francis Broderick summarized Du Bois's alternative to the Atlanta Compromise (in 1904) as: "... full political rights [for blacks] on the same terms as other Americans; higher education of selected Negro youth; industrial education for the masses; common school training for every Negro child; stoppage of the campaign of self-deprecation; careful study of the real condition of the Negro; a national Negro periodical; thorough and efficient federation of Negro societies and activities; raising of a defense fund; judicious fight in the courts for civil rights." Broderick quotes Du Bois: "Finally the general watch word must be, not to put further dependence on the help of the whites but to organize for self-help, encouraging 'manliness without defiance, conciliation with[out] servility.'"[74]

- ^ Du Bois documented his disappointment in an essay titled "The Parting of Ways."[76]

- ^ Scottish essayist William Archer wrote: "At best, indeed, the Southern kindliness of feeling towards the individual Negro subsisted only so long as he 'knew his place' and kept it; and the very process of education and elevation on which Mr. Washington relies renders the Negro ever less willing to keep the place the Southern white man assigned him. In the North, while the dislike of the individual has greatly increased, the theoretical fondness for the race has very perceptibly cooled. Altogether, the tendency of events since 1895 has not been in the direction of the Atlanta Compromise. The Atlanta riot of eleven years later was a grimly ironic comment on Mr. Washington's speech."[93]

- ^ The document asking blacks to remain in the South was the 1917 report from the annual Tuskegee Negro Conference.[104]

- ^ Norrell wrote: "Led by Du Bois ... historians confused the style with the substance of Booker T. Washington. Many historians have shown a narrow-mindedness about black leaders' styles: African-American leaders must always be 'lions' like Frederick Douglass, Du Bois, Martin Luther King Jr., or Jesse Jackson. They cannot be 'foxes' or 'rabbits', else they will be accused of lacking manhood."[110]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Jones 1999, pp. 146–162.

- ^ "13th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States". National Museum of African American History & Culture. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- ^ "Civil Rights and Reconstruction". The Historical Society of the New York Courts. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Foner 2025.

- ^ Gary, Shannon (2008). "Tuskegee University". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Alabama Humanities Foundation. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Norrell 2009a, pp. 45, 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l English 2009.

- ^ a b Perman 2001, pp. 1–36, 321–328.

- ^ Norrell 2009a, p. 126.

- ^ Norrell 2009a, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. xix.

- ^ Harlan 1988, p. 164.

- ^ Taylor 1938.

- ^ a b c d Aiello 2016, pp. 33, 151–152, 259.

- ^ a b c Alexander 2013, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alridge 2020.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 36, 40.

- ^ Additional information about the speech is found in:

• Aiello 2016, pp. 36–40.

• Lewis 2009, pp. 180–181.

• Croce 2001, pp. 1–3.

• Johnston. - ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Bauerlein 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Aiello 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Walden 1960, p. 108.

- ^ a b Du Bois 1903, p. 54.

- ^ Norrell 2009a, p. 277.

- ^ Woodward 1974, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Harlan 1988, p. 165. Harlan describes the Atlanta Compromise as a "bargain" between Southern blacks and whites.

- ^ a b

Additional details about the elements of the Atlanta Compromise are found at:

• English 2009.

• Lewis 2009, pp. 180–181.

• Croce 2001, pp. 1–3.

• Johnston.

• Cummings 1977. - ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 36–40.

- ^ Cummings 1977, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. 33.

- ^ English 2009, p. 108.

- ^ a b c "Booker T. Washington and the 'Atlanta Compromise'". National Museum of African American History & Culture. Retrieved May 7, 2025.

- ^ Johnston.

- ^ Meier 1963, pp. 85–90.

- ^ Meier 1963, p. 98.

- ^ a b Brown 1999, pp. 123–126.

- ^ a b Gasman & McMickens 2010.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. xviii.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. xv, 33, 45.

- ^ Harlan 1988, pp. 9, 16.

- ^ Aiello 2016, p. 38. Portion of the speech containing the "finger" simile.

- ^ a b Walden 1960, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Harlan 1971, pp. 393–395.

- ^ "Robert Moton and the Colored Advisory Commission". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- ^ a b c Cummings 1977, p. 79.

- ^ Walden 1960, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Anderson 1988, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 55, 65–66, 73–76.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 202–207.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 70-71. Footnote #11. William Calvin Chase.

- ^ Fox 1970, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Lewis, pp. 179–182.

- ^ Fox 1970, p. 27.

- ^ Fox 1970, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Alexander 2013, p. 213.

- ^ Alexander 2013, pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b Fox 1970, pp. 49–58.

- ^ a b c Pole 1974, pp. 889–890.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. xx.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. xvi, 46.

- ^ Harlan 1972, p. 225. "Let me heartily congratulate you upon your phenomenal success at Atlanta – it was a word fitly spoken".

- ^ Bauerlein 2005.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. xii, 73.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. xxvii–xviii.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. xii.

- ^ a b Du Bois, W. E. B. (July 1901). "The Evolution of Negro Leadership". The Dial. Vol. 31. pp. 53–55. ISSN 2159-4643. Retrieved May 5, 2025.

- ^ Du Bois 1903, p. 50.

- ^ Walden 1960, p. 110.

- ^ Du Bois 1903a, p. 63.

- ^ Brown 1999, p. 124.

- ^ Aiello 2016, p. 201.

- ^ a b Broderick 1974, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 201, 225–227, 231.

- ^ Du Bois, W. E. B. (April 1904). "The Parting of Ways". World Today. 6: 521–523.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, pp. 259–292.

- ^ Du Bois, W. E. B. (January 1905). "In Account with the Year of Grace Nineteen Hundred and Four: Debit and Credit". The Voice of the Negro. Vol. 2, no. 1. p. 677. Retrieved May 3, 2025 – via Hathi Trust. Although Washington was not mentioned by name, Du Bois wrote "... $3000 of 'hush money' used to subsidize the Negro press in five leading cities."

- ^ Bauerlein 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Woodward 1974, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Broderick 1974, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Anderson 1988, pp. 140, 153, 166.

- ^ Anderson 1988, pp. 66, 86, 137, 153.

- ^ "Black Education and Rockefeller Philanthropy from the Jim Crow South to the Civil Rights Era". Rockefeller Archive Center. September 11, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ Woodward 1974, p. 160.

- ^ a b "Jim Crow Laws and Racial Segregation". VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project. Virginia Commonwealth University. January 20, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- ^ Alexander 2013, p. 70.

- ^ Woodward 1974, p. 157.

- ^ SeguinRigby 2019.

- ^ a b Finkelman 2009.

- ^ Coates, Ta-Nehisi (March 31, 2009). "The Tragedy and Betrayal of Booker T. Washington". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825. Coates characterizes the race riots as "the pogroms that greeted Booker T's compromise."

- ^ a b c Capeci 1996, pp. 735, 744–749.

- ^ Archer 1910.

- ^ Croce 2001, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Fox 1970, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Aiello 2016, pp. 293–340.

- ^ "The Niagara Movement: Declaration of Principles (1905)" (PDF). Retrieved May 3, 2025. Text of the Niagara Movement's Declaration of Principles.

- ^ Aiello 2016, p. 373.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, pp. 373–399.

- ^ a b c Factor 1970, pp. 347–348.

- ^ a b O'Reilly 1997.

- ^ "The Second Great Migration". The African American Migration Experience. The New York Public Library. 2005. Retrieved May 4, 2025.

- ^ Gregory 2009.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, p. 511.

- ^ Marable 1977.

- ^ Matthews 1976.

- ^ Walden 1960, p. 114.

- ^ a b Aiello 2016, pp. xix–xx.

- ^ Wendt 2009.

- ^ a b c Norrell 2003, p. 107.

- ^ Capeci 1996, p. 735.

- ^ Walden 1960, p. 112.

- ^ Norrell 2009a, pp. 434–435.

- ^ a b Norrell 2003.

- ^ Cummings 1977, pp. 76, 80–81.

- ^ Norrell 2009, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Norrell 2003, p. 109.

- ^ Capeci 1996, pp. 743–749.

- ^ Harlan 1988, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Harlan 1971, p. 396.

- ^ Walden 1960, pp. 114–115.

Sources

[edit]- Aiello, Thomas (2016). The Battle for the Souls of Black Folk: W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and the Debate That Shaped the Course of Civil Rights. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781440843587.

- Alexander, Shawn (2013). An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP. Politics and culture in modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812222449. Retrieved June 28, 2025.

- Alridge, Derrick (2020). "Atlanta Compromise Speech". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 3, 2025.

- Anderson, J.D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807842214.

- Archer, William (1910). "Four Possibilities: II. The Atlanta Compromise". Through Afro-America: an English reading of the race problem. E. P. Dutton & Co. pp. 208–210. hdl:2027/uc1.31175010654476. OCLC 867981446. Retrieved May 3, 2025.

- Bauerlein, Mark (2005). "Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois: The Origins of a Bitter Intellectual Battle". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 46 (46): 106–114. doi:10.2307/4133693. Retrieved May 4, 2025.

- Broderick, Francis (1974) [1962]. "The Fight Against Booker T. Washington". In Hawkins, Hugh (ed.). Booker T. Washington and His Critics. Heath. pp. 67–80. ISBN 0669870498. Retrieved June 22, 2025.

- Brown, M. Christopher (1999). "The politics of industrial education: Booker T. Washington and Tuskegee State Normal School, 1880-1915". The Negro Educational Review. 50 (3): 123. ISSN 0548-1457.

- Capeci, Dominic (1996). "Reckoning with Violence: W. E. B. Du Bois and the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot". The Journal of Southern History. 62 (4): 727–766. doi:10.2307/2211139. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- Croce, Paul (2001). W. E. B. Du Bois: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29665-9. Retrieved May 3, 2025.

- Cummings, Melbourne (1977). "Historical Setting for Booker T. Washington and the Rhetoric of Compromise, 1895". Journal of Black Studies. 8 (1): 75–82. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others". The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. A. C. McClurg. pp. 41–59. OCLC 43569072.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903a). "The Talented Tenth". In Washington, Booker T. (ed.). The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative American Negroes of To-Day. J. Pott. pp. 31–75. LCCN 03023404. Retrieved May 7, 2025.

- English, Bertis (2009). "Atlanta Exposition Address (Atlanta Compromise)". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 106–109. ISBN 9780195167795. Retrieved May 9, 2025.

- Factor, Robert (1970). The Black Response to America: Men, Ideals, and Organization, from Frederick Douglass to the NAACP. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0201020033. Retrieved June 28, 2025.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2009). "Lynching and Mob Violence". Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 220–231. ISBN 9780195167795. Retrieved May 9, 2025.

- Foner, Eric (May 27, 2025). "Reconstruction". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 7, 2025.

- Fox, Stephen (1970). The Guardian of Boston: William Monroe Trotter. Atheneum Press. ISBN 0689702566. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- Gasman, Marybeth; McMickens, Tryan L. (2010). "Liberal or Professional Education?: The Missions of Public Black Colleges and Universities and Their Impact on the Future of African Americans". Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society. 12 (3). Taylor & Francis: 286–305. doi:10.1080/10999949.2010.499800.

- Gregory, James N. (2009). "The Second Great Migration: An Historical Overview". In Trotter Jr., Joe W.; Kusmer, K.L. (eds.). African American Urban History since World War II. Historical Studies of Urban America. University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780226465098. Retrieved May 4, 2025.

- Harlan, Louis (1971). "The Secret Life of Booker T. Washington". The Journal of Southern History. 37 (3). ISSN 2325-6893. Retrieved May 19, 2025.

- Harlan, Louis (1972). Booker T. Washington: the Making of a Black Leader, 1856–1901. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195019156. Retrieved May 19, 2025. Title of this book is sometimes reported as Booker T. Washington.

- Harlan, Louis (1983). Booker T. Washington: the Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901–1915. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195042298.

- Harlan, Louis (1988). "Booker T. Washington and the Politics of Accommodation". In Smock, Raymond (ed.). Booker T. Washington in Perspective. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1578069289. Retrieved June 22, 2025.

- Johnston, Mindy (ed.). "Atlanta Compromise". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 3, 2025. Includes full text of Washington's 1895 "Atlanta Compromise" speech.

- Jones, Howard (1999). Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 080327565X.

- Lewis, David (2009). W. E. B. Du Bois: A Biography 1868-1963. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0805088052. Retrieved May 3, 2025.

- Marable, Manning (1977). "Tuskegee Institute in the 1920's". Negro History Bulletin. 40 (6): 764–768. ISSN 0028-2529.

- Matthews, Carl S. (1976). "Decline of Tuskegee Machine, 1915-1925-Abdication of Political-Power". South Atlantic Quarterly. 75 (4): 460–469. doi:10.1215/00382876-75-4-460. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- Meier, August (1963). Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington. University of Michigan Press. LCCN 63014008. Retrieved June 21, 2025.

- Norrell, Robert J. (2003). "Booker T. Washington: Understanding the Wizard of Tuskegee". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 42: 96–109. doi:10.2307/3592453. Retrieved June 18, 2025.

- Norrell, Robert J. (2009). "Have Historians Given Booker T. Washington a Bad Rap?". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 62: 62–69. Retrieved June 18, 2025.

- Norrell, Robert J. (2009a). Up from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington. Harvard University Press. ISBN 067403211X. Retrieved June 28, 2025.

- O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 17: 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711.

- Perman, Michael (2001). Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. The Fred W. Morrison series in Southern studies. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807849095. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- Pole, Jack (1974), "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others", The Historical Journal, 17 (4): 883–893, doi:10.1017/S0018246X00007962.

- Logan, Rayford Whittingham, The Betrayal of the Negro, from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson, Da Capo Press, 1997, pp. 275–313.

- Seguin, Charles; Rigby, David (2019). "National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941". Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. 5. doi:10.1177/2378023119841780. ISSN 2378-0231. S2CID 164388036. Retrieved May 3, 2025.

- Taylor, A. A. (January 1938). "Historians of the Reconstruction". The Journal of Negro History. 23 (1): 16–34. doi:10.2307/2714704. Retrieved April 15, 2025.

- Walden, Daniel (1960). "Historians of the Reconstruction". The Journal of Negro History. 45 (2): 103–115. doi:10.2307/2716573. Retrieved June 15, 2025.

- Wendt, Simon (2009). "Civil Rights Movement". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 411–419. ISBN 9780195167795. Retrieved May 9, 2025.

- Woodward, C. Vann (1974) [1962]. "The Atlanta Compromise". In Hawkins, Hugh (ed.). Booker T. Washington and His Critics. Heath. pp. 156–166. ISBN 0669870498. Retrieved June 22, 2025.

External links

[edit]- "Atlanta Compromise" Full text of Washington's 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech.

- "Booker T. and W. E. B." 1969 poem by poet Dudley Randall about the conflict between Washington and Du Bois.

- 1895 in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1900s neologisms

- African-American history between emancipation and the civil rights movement

- African-American segregation in the United States

- Booker T. Washington

- Democratic backsliding in the United States

- Electoral restrictions

- Historically black universities and colleges in the United States

- History of Atlanta

- History of African-American civil rights

- History of racial segregation in the United States

- History of voting rights in the United States

- History of the Southern United States

- Jim Crow

- Reconstruction Era

- W. E. B. Du Bois

- White supremacy in the United States