Arlington County, Virginia

Arlington County | |

|---|---|

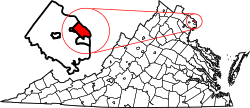

Location within the U.S. state of Virginia | |

Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 38°52′49″N 77°06′30″W / 38.880278°N 77.108333°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 27, 1801 |

| Named after | Arlington House |

| Area | |

• Total | 26 sq mi (70 km2) |

| • Land | 26 sq mi (70 km2) |

| • Water | 0.2 sq mi (0.5 km2) 0.4% |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 238,643 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 8th |

| Website | arlingtonva.us |

Arlington County, or simply Arlington, is a county in the U.S. state of Virginia.[1] The county is located in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from Washington, D.C., the national capital.

Arlington County is coextensive with the U.S. Census Bureau's census-designated place of Arlington. Arlington County is the eighth-most populous county in the Washington metropolitan area with a population of 238,643 as of the 2020 census.[2] If Arlington County were incorporated as a city, it would rank as the third-most populous city in the state. With a land area of 26 square miles (67 km2), Arlington County is the geographically smallest self-governing county in the nation.

Arlington County is home to the Pentagon, the world's second-largest office structure, which houses the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense. Other notable locations are DARPA, the Drug Enforcement Administration's headquarters, Reagan National Airport, and Arlington National Cemetery. Colleges and universities in the county include Marymount University and George Mason University's Antonin Scalia Law School, School of Business, the Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, and Schar School of Policy and Government. Graduate programs, research, and non-traditional student education centers affiliated with the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech are also located in the county.

Corporations based in the county include the co-headquarters of Amazon, several consulting firms, and the global headquarters of Boeing, Raytheon Technologies and BAE Systems Platforms & Services.[3]

History

[edit]Native American settlement

[edit]Arlington County was inhabited by prehistoric Native American cultures from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians 10,000 years before European colonization.[4] Archeological evidence, including pottery fragments, tools, and arrowheads, suggests sporadic habitation during the Archaic Period, with more permanent communities during the Formative stage and Early Woodland period.[5] Some objects unearthed during archeological digs have been found to be from as far as southern Ontario, indicating the existence of a trade route that ran through the area.[6]

When John Smith made contact in 1608, Arlington was populated by the Nacotchtank, an Eastern Algonquian-speaking people that were likely part of the Powhatan Confederacy.[7] He identified a village named Nameroughquena near the present-day 14th Street bridges.[7] The Nacotchtank farmed, hunted, and fished along the nearby Anacostia River, where they had more villages.[8]

Later in the 17th century, the Nacotchtank became involved in the regional beaver trade instigated by Henry Fleete, which while enabling the Nacotchtank to build wealth, undermined traditional social structures and ultimately weakened them.[9] Further pressures, including population loss due to the spread of infectious diseases from Europeans, warfare with encroaching British colonizers, and conflict with Native American tribes in northern regions forced the Nacotchtank to abandon their homeland.[10][7] By 1679, they had fully left the area and were absorbed into the Piscataway.[7]

Colonial era

[edit]Colonists began migrating from Jamestown and towards the Potomac River between 1646 and 1676, during which land speculation in the region increased substantially.[11] Early grants were issued in the mid-17th century by the Governor on behalf of the Crown to prominent figures of Virginia society; many never inhabited their landholdings during this period.[11][12] The first "seated" grant in the area was the Howson Patent, which John Alexander purchased from Captain Robert Howson on November 13, 1669, and populated with tenants by 1677.[13] With the establishment of the Northern Neck Proprietary after the restoration of Charles II in 1660, future land grants in the region were made by inheritors of Northern Neck, namely the Lords Fairfax.[14]

After colonists depopulated the area in the aftermath of Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, migration to Northern Neck began to grow by the end of the 17th century. The increase in population justified the formation of Prince William County from parts of Stafford County in 1730, and in 1742 Fairfax County, of which present-day Arlington County was part.[15] Early settlement patterns were defined by large plantations along waterways, where planters built wharfs that provided access to colonial trade networks.[16] This included Abingdon Plantation, which was established by John Alexander's grandson Gerard by 1746 and was the Arlington area's first mansion house.[17][18] Log cabins, such as the home built by John Ball in the mid-18th century, were common among Arlington's yeoman farming community.[19]

Indentured servants and enslaved labor worked the land, the latter of which are first documented being in the Arlington area in 1693 and were owned by the wealthiest planters, such as the Masons and Washingtons.[20][21] Tobacco was the dominant crop grown in Arlington until local soil was exhausted by the late 18th century, motivating tobacco planters to move further inland; remaining farmers turned to growing alternatives such as corn.[18][22] Colonists also built gristmills along Arlington's creeks and engaged in fishing along the Potomac.[23] Rudimentary roads, some of which were first established by Native Americans, and ferries along the Potomac connected residents and plantations with emerging towns such as Alexandria and Georgetown.[24] The former served as the region's primary shipping and commercial district.[25]

Revolutionary war and formation of federal district

[edit]The Stamp Act and Townshend Acts passed by the Parliament of Great Britain in the 1760s motivated planters and farmers in Fairfax County, including George Mason, George Washington, and members of the Ball family to sign agreements not to import or purchase British goods in protest.[26] Mason later authored the Fairfax Resolves in 1774 in opposition to the policies, which were adopted by him and other landowners.[26]

Following the Richmond Convention in 1776, Fairfax County formed a Committee of Safety that collected taxes for the war effort and enforced bans on trade with Britain.[27] Local Fairfax militia formed before the war were dissolved after the Richmond Convention ordered for the organization of a regular state force in July 1775.[28] Men were recruited from Fairfax County and joined the Virginia state regiment that were incorporated into the Continental Army by 1776.[29] While the area did not see significant action during the war, Alexandria was the home port for part of the Virginia State Navy; some ships operated as privateers.[30] Part of Rochambeau's forces likely camped near Theodore Roosevelt Island on their way to Yorktown in 1781.[31]

After American independence from the British Empire was achieved following the Treaty of Paris and the Constitution was instituted in 1789, the federal government set about establishing the United States' seat of government, which Article 1, Section 8 enabled through the power to acquire an area of no more than ten square miles for the nation's capital.[32] The Residence Act passed by Congress on July 17, 1790, which decreed that the federal district be located on the Potomac River between the "mouths of the Eastern Branch and the Conogochegue", settled the rivalry between states on claiming the location of the capital city.[32] President George Washington commissioned a survey to define its borders, which reached down to Hunting Creek and were consequently beyond the Residence Act's limits; this required an amendment that was passed on March 3, 1791.[32]

In 1789, Virginia had offered to cede ten square miles or less and provide funding for the construction of public buildings. Congress accepted this as a part of the federal district, but specified that no public buildings would be erected in the Virginia section of the capital.[32] Boundary stones were placed at one miles intervals along the borders of the district starting on April 15, 1791.[32] The federal government and Congress moved to the new city of Washington within the District of Columbia in 1800; the Virginia section, which included Alexandria, became known as Alexandria County through the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.[33]

Antebellum period

[edit]

In the early 19th century, the land outside of Alexandria, termed the "country part" of Alexandria County and representative of present-day Arlington, remained rural and dominated by several large plantations and smaller farms. Migration from northern states such as New York and Pennsylvania brought investment and improved farming methods.[34] Small communities established along the intersections of Alexandria County's growing road network, including Ball's Crossroads, became gathering places for local residents.[35] The county's free black population, which consistent of 235 individuals outside of Alexandria in 1840, lived throughout the area in small clusters and among white neighbors.[36] While agriculture, particularly of corn and grain, was the county's main economic output in the first half of the 19th century, some residents worked in various trades and factories in Alexandria.[37] Other non-farming occupations included fishing and brickmaking.[38]

Enslaved African Americans consisted of around 26% of the population in 1810, working on properties such as George Washington Parke Custis's Arlington Plantation, which Custis established with his inheritance from John Parke Custis, step-son of George Washington, in 1802; this included 18,000 acres of land across Virginia and 200 slaves, 63 of which worked on building and maintaining the plantation.[39][40] The prominent African American Syphax family, whose matriarch Maria Carter Syphax was an illegitimate daughter of Custis and enslaved maid Arianna Carter, originated as enslaved servants on the Arlington estate; Custis later manumitted Maria and her children in 1845 and granted them 17 acres of land.[41][42] Custis was the largest slave owner in the area until his death in 1857.[18]

The population share of the enslaved dropped to around 20% by 1840 as a consequence of the continued movement away from labor-intensive tobacco farming and the slave trade with Deep Southern states and territories.[18] Alexandria became a national center of this trade, with firms like Franklin & Armfield pioneering in the trafficking of enslaved people from around the Chesapeake region to New Orleans and the Forks in the Road slave market in Natchez, where they were sold to the Deep South's growing cotton plantations.[43]

Major infrastructure, including the Chain Bridge, Long Bridge, and Aqueduct Bridge, was built in the first half of the 19th century to better connect the District of Columbia with the surrounding region.[44] Toll roads were established between Alexandria, Georgetown, Leesburg, and other major settlements to facilitate the improvement and maintenance of thoroughfares, some of which also funded bridge construction.[45] The Alexandria Canal, which via the 1843 Aqueduct Bridge connected Alexandria to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in Georgetown, was opened in 1846.[46] Alexandria County's first railway, the Alexandria and Harper's Ferry Railroad, was chartered in 1847; it later became part of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad.[47] Infrastructure expansion drove the Jackson City speculative development, which was established in 1835 by a group of investors from New York at the foot of Long Bridge. Their vision of Jackson City as a rival port to Georgetown and Alexandria was never realized, as the settlement failed to receive a charter from Congress owing to opposition from residents Georgetown and Washington.[48]

Retrocession

[edit]![1838 map of the Alexandria Canal. Alexandria County's public debts from this and other projects amounted to nearly $2 million.[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Map_of_Alexandria_Canal_1838.jpg/500px-Map_of_Alexandria_Canal_1838.jpg)

The reintegration of Alexandria County into Virginia had been raised intermittently since the formation of the District, particularly by townspeople in Alexandria.[46] Congressional debate of the issue began with discussion of the 1801 Organic Act and its implications, focusing on the lack of political rights afforded to District residents,[51] who were not permitted to vote or have representation in Congress.[52] Economic concerns relating to insufficient federal investment in infrastructure like the Alexandria Canal, which left Alexandria heavily indebted, motivated merchants and leaders in Alexandria to consider retrocession by the 1830s.[53] The argument went that rejoining Virginia would bring financial relief to the municipal budget, greater support for economic development, restored political rights, and free Alexandria County from "antiquated" statutes Congress had inherited from older colonial laws and not updated.[54]

Congress's failure to recharter banks in the District further frustrated Alexandria's business community,[55] and in 1840 the Common Council of Alexandria convened a county-wide referendum on retrocession, with a majority voting in favor.[56] After several years of lobbying by a committee of Alexandrians, the Virginia General Assembly introduced state legislation in July 1846 to accept Alexandria County back into Virginia territory if Congress agreed.[56] Congress passed the Retrocession Act later that month that authorized the return of Alexandria County to Virginia pending another county referendum.[57]

"The act of retrocession is an act in clear and obvious hostility to the spirit and provisions of the constitution of the United States, and beyond the possibility of honest doubt, null and void; That therefore we respectfully invoke the senate and house of assembly to disregard and give no countenance or head to any so-called commissioners or representative pretending or purporting to speak for and in behalf of the citizens of the county of Alexandria, and more especially of the citizens of the country part of the same."

The referendum, held on September 1 and 2, passed with overwhelming support from Alexandrians, but was rejected by residents in the broader county;[57] many in Alexandria County questioned the constitutionality of retrocession and felt marginalized by a movement that was primarily driven by Alexandria's business interests.[59] George Washington Parke Custis, who had originally opposed retrocession due to concerns about the county's finances, changed sides after the Virginia General Assembly agreed to take on the debt incurred by the Alexandria Canal construction.[57][58] Alexandria County was officially returned to Virginia on March 13, 1847, after the Virginia General Assembly passed the state's retrocession bill.[60]

Beyond the freeholding whites in Alexandria County who were able to participate in the referendum, Alexandria County's free black community was also opposed to retrocession, as they anticipated the pro-slavery Virginia government would encroach upon their rights and institutions. This fear was realized soon after retrocession, when Virginia closed most of Alexandria County's black schools and imposed Black Codes upon all free African Americans.[61][62]

While not mentioned prominently in contemporary debates about retrocession, modern historians and other figures have since argued that the future of slavery in Alexandria and Virginia more broadly was a significant factor.[63] Growing domestic and international abolitionist sentiments stoked fears in Alexandria that slavery would eventually be abolished in the District of Columbia and by extension threaten the town's lucrative slave trade.[64] This ultimately came to pass as a part of the Compromise of 1850, which banned Washington's slave trade.[65] In 1907, Alexandria County attorney Crandal Mackey wrote that, given Alexandria County's existence as a destination for runaway enslaved people, Alexandrians thought they would be better served by the enforcement of slaveowners' property rights that would be guaranteed by Virginia's pro-slavery government.[66] Retrocession also enabled the pro-slavery faction of the Virginia General Assembly to add two safe seats, strengthening their position against non-slave owning, abolitionist-leaning constituencies in Western Virginia.[57][66]

Civil War

[edit]The "country part" of Alexandria County leaned strongly Unionist, as indicated by the results of the May 23, 1861 vote held on the ratification of Virginia's Ordinance of Secession; despite reports of voter intimidation from secessionists, two-thirds voted against the Ordinance.[67] This was in part a result of the migration from northern states into Arlington County during the first half of the 19th century, some of whom were sympathetic to abolitionism and the Republican Party.[68] Regardless, Virginia voted overwhelmingly in favor of secession and joined the Confederacy.[69] Robert E. Lee, a colonel in the U.S. Army, son-in-law of George Washington Parke Custis, and owner of Arlington Plantation following Custis's death, left for Richmond with his family on April 22, 1861, to accept command of Virginia's army.[70]

Union occupation

[edit]

The proximity of Alexandria County to Washington, as well as the direct lines of sight it offered to important landmarks, necessitated the construction of defenses to protect the capital.[71] After engaging in brief reconnaissance activities, the Union Army moved three units into Alexandria County on the night of May 23, 1861, with commanding officer General Joseph K. Mansfield establishing a regional headquarters at Arlington Plantation.[71] Work began immediately on a series of fortifications that eventually became the Arlington Line of the Civil War Defenses of Washington. These included forts and rifle trenches along Arlington Heights, thoroughfare intersections, and bridgeheads.[71][72] The Confederate victory at the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 increased the urgency of completing Washington's defenses,[73] which were mostly finished by the end of that year.[74] The Union Army also built roads, such as Military Road, to enable improved communications and transport along the defensive line.[75] Construction of forts and improvements continued up to 1863.[75]

The Union occupation significantly altered the landscape of Alexandria County. Defensive works required the logging of forests and trenches that cut through farmland.[76] Union troops repurposed private homes and public buildings as hospitals and other facilities.[77] Many properties were left decimated following troop encampments and the razing of structures for timber and other resources.[78] Confederate sympathizers, many of whom were local officials, left after the arrival of Union soldiers, which created gaps in governance; General William Reading Montgomery addressed this by creating a military court that tried military and civilian cases, which was eventually closed after local criticism.[79]

Military engagements

[edit]

Throughout the war, Alexandria County only saw minor skirmishes between Union and Confederate forces. Confederate parties began engaging in guerrilla tactics against Union outposts in early June 1861,[80] including a minor clash at Arlington Mill on June 2.[81] The most significant battle took place in August 1861 at Ball's Crossroads, when Confederates stationed at Munson's Hill in Fairfax County penetrated the Union line as far as Hall's Hill, which they shelled before being driven back by Union cavalry.[82][83] Union forces also operated the Balloon Corps in Alexandria County until 1863 to perform aerial reconnaissance on nearby Confederate encampments and activities.[84]

Arlington Cemetery and Freedman's Village

[edit]Congress's June 1862 enactment of an assessment of taxes owed by Southern property owners, and subsequent enforcement of tax collection, resulted in the Lee family owing $92.07 on Arlington plantation.[85] Mary Anna Custis Lee sent a relative to pay this, which was rejected given her absence.[85] The federal government then seized Arlington estate and purchased it at a public auction held on January 11, 1864, on orders from President Abraham Lincoln.[86] Following this purchase, the Quartermaster General's Office, in search of a burial site for the many Union casualties at the Battle of the Wilderness, selected Arlington in May 1864 for its scenic beauty and association with Robert E. Lee.[87] The first military burial took place on Mary 13, 1864, around one month before the cemetery was officially established.[88]

The rise in contraband migrants from the South into Washington, and the overcrowded camps that accommodate them, motivated the Department of Washington to establish the Freedman's Village settlement for emancipated enslaved people on the grounds of Arlington.[89][90] Founded on December 4, 1863, Freedman's Village, unlike other contraband camps, was envisioned as a model community for African Americans transitioning out of enslavement.[90] The Village provided its inhabitants with instruction in trades, housekeeping, and general education; many were employed by the Union Army and paid a regular wage.[91] Secretary of State William H. Seward often toured prominent visitors around Freedman's Village to demonstrate the Villagers' progress.[92] Many organizations, including churches and fraternities, were founded by Villagers during this period that became the social foundation of Arlington's black community.[93]

Reconstruction through 1900

[edit]Years of occupation by Union troops left Alexandria County's economy in poor condition after the war; thousands of acres of farms and woodland had been destroyed.[94] Local landowners who applied for compensation through the Southern Claims Commission generally received much less than they requested.[78] Some financially ruined residents sold off parcels of land at low rates to formerly enslaved people migrating into Alexandria County from rural Virginia and Maryland, eventually creating black enclaves like Hall's Hill.[95]

Changes in municipal governance in Virginia's 1870 Constitution required that all counties be divided into three or more districts, excluding any cities with a population greater than 5,000. This administratively separated Alexandria from the rest of the county and divided Alexandria County into the Arlington, Jefferson, and Washington Districts, with each having its own elected offices, public schools, and other facilities.[96][97] The Reconstruction Amendments passed along with the 1870 Constitution enabled Alexandria County's eligible black voters to participate in district and county-level elections, resulting in local black politicians, such as John B. Syphax, rising to elected office.[98] This was especially the case in the Jefferson District, which contained Freedman's Village and became a center of black political power in the county.[98]

While this constituency was initially associated with the Republican Party, the rise of Virginia's Conservative Party, which opposed black suffrage and other Reconstruction-era reforms,[99] eventually led to the Republicans abandoning their commitments to racial equality.[100] Dissatisfied black voters, as well as white working class communities associated with the labor movement, flocked to the Readjuster Party, a newly established progressive populist party that opposed Virginia's old planter establishment and controlled the General Assembly by 1879.[100][101]

White conservatives that wanted to reinstate their political and social dominance challenged the ascendency of Alexandria County's black community by the 1880s. Through an orchestrated smear campaign in the local press, they contributed to the closure of Freedman's Village in 1887, which had by that point lost the support of the federal government.[102][103] White conservatives also prevented elected black officials from taking office either through claims about "inexperience" or identifying failed payments of election dues.[102] This occurred during a broader political shift in Virginia towards Southern Democrats, who successfully undermined the Readjuster Party's interracial coalition with a reactionary, racist platform by 1885.[104]

Starting in the 1880s, local railroad companies began constructing an interurban trolley system in Alexandria County that eventually provided commuter services to Washington by 1907.[105] This facilitated the establishment of suburban subdivisions, such as Clarendon, along the trolley lines by 1900.[105] Population growth, as well as the inconvenience of running the county's affairs from the old courthouse in Alexandria, drove the General Assembly to enact legislation that enabled residents to vote if the courthouse should be relocated.[106] After a majority voted in favor of the motion, the county's new courthouse was completed on the old site of Fort Woodbury in 1898.[106]

20th century suburbanization and Jim Crow segregation

[edit]

In the first several decades of the 20th century, Alexandria County, officially renamed to Arlington County after the Arlington estate in 1920,[107] rapidly developed into a commuter suburb of Washington. The ten-year period between 1900 and 1910 saw the creation of 70 new communities and subdivisions.[108] Community organizations were established in these neighborhoods to advocate for their residents.[109] During this period, the City of Alexandria succeeded in annexing significant portions of Arlington's southern area in 1915 and 1929; further annexations were prevented by the General Assembly in 1930.[110]

Developers and political figures such as Frank Lyon and Crandal Mackey, who were members of the Southern Progressive movement, advocated for county-wide infrastructure improvements and the removal of "areas of vice" to facilitate continued suburbanization.[111] This included Rosslyn, an interracial neighborhood which had developed a series of gambling halls and saloons beginning in the 1870s.[112] Lyon and Mackey established the Good Citizen's League in the 1890s, which consisted of Arlington's wealthiest and most influential residents, to push for these changes.[111] Consistent with other Southern Progressives during the Jim Crow era, the Good Citizen's League sought to modernize Arlington while maintaining its racial hierarchy through segregation and other means.[111] League members conducted violent "clean up" raids, most infamously in Rosslyn in 1904,[112] participated in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1901–02 that disenfranchised black voters through poll taxes,[113] and developed white suburban subdivisions via racially restrictive housing covenants.[114]

The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized "separate but equal" racial segregation enabled the Virginia Assembly to pass zoning ordinances in 1912 that created "segregation districts" throughout the state, which were adopted in Arlington.[115] While these eventually struck down by the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision, county planners and developers restricted the growth of black neighborhoods in other ways, including through Arlington's 1930 zoning ordinance that prevented further construction of more affordable multifamily housing in black communities.[116] The effect of these policies was the stagnation of Arlington's black population, which declined from 38% of Arlington's population in 1900 to around 12% by 1930.[117] Blacks were forced to concentrate in a few overcrowded enclaves as the county's white population increased rapidly with the growth of whites-only suburban subdivisions. These subdivisions gradually encroached upon black neighborhoods, and by 1950 only three black communities remained in the county; 11 had existed in 1900.[118]

New Deal through Civil Rights

[edit]Beginning in the New Deal era, Arlington County experienced an inflow of federal workers.[119] While the Great Depression stalled residential development, incoming government employees instigated further growth and the population doubled between 1930 and 1940.[120][121] Public housing projects such as Colonial Village backed by the Federal Housing Administration were built across Arlington to help house its expanding population; consistent with Arlington's Jim Crow policies, these communities were closed off to Arlington's black residents and other minority groups.[122] New Deal programs, such as the Public Works Administration, also supported the continued improvement of Arlington's infrastructure, including the completion of an overhauled sewer system in 1937 and renovations to local public schools.[123][124] Rising car ownership caused the closure of Arlington's trolley lines during the 1930s; these were replaced with a public bus system.[125] Washington National Airport, later renamed after President Ronald Reagan in 1998, opened in 1941 on land formerly occupied by the Abingdon Plantation.[126]

Arlington's population increase fundamentally altered its politics. Its traditional Southern Democratic political establishment, which favored racial segregation and consisted of Southerners in the mold of Mackey and Lyon, was gradually replaced with more liberal, New Deal Democrats and white moderates.[127] These figures fought for greater investment in public education and infrastructure in Arlington, often against opposition in Richmond, where the Democratic Party's socially and fiscally conservative Byrd Machine had dominated the General Assembly since the early 20th century.[128] These developments coincided with a rising civil rights movement in Arlington, reflected in the establishment of its NAACP branch in 1940 and Green Valley resident Jessie Butler's legal challenge to Virginia's poll tax in 1949.[129]

The entry of the U.S. into World War II drove expansion in government that had a significant impact on Arlington County. Massive facilities such as the Pentagon and Navy Annex were built to support military operations.[130] These, along with infrastructure like the Shiley Memorial Highway, required the demolition of Queen City and East Arlington, two historic black communities that had been established shortly after the closure of Freedman's Village.[131][132] The federal government at first housed displaced residents in several trailer camps after an intervention by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt;[133] poor living conditions resulted in both being closed by 1949.[134] Roosevelt further pressured the Federal Public Housing Authority in 1944 to provide more housing to Arlington's African American community, resulting in the construction of a 44-unit public housing project in Johnson's Hill for black residents that year; many leaving the trailer camps moved into this property.[135] By comparison, white residents had access to thousands of public housing units during this period, and none were housed in trailer camps.[135]

Arlington's NAACP and other civil rights organizations continued fighting the county's prevailing racial segregation through a series of legal challenges, particularly after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court ruling that struck down "separate but equal" segregation under Plessy v. Ferguson. Reactionary political forces and organizations, including Virginia's massive resistance program against racial integration in schooling led by former government and Senator Harry F. Byrd and local Arlington hate groups such as George Lincoln Rockwell's American Nazi Party and the KKK, rose in opposition to this civil rights activism and Arlington's increasing liberalism.[136]

A 1956 lawsuit by NAACP and three residents from Hall's Hill against Arlington's segregation in schooling initiated an extended legal fight that lasted until February 2, 1959, when Stratford Junior High School in Cherrydale was racially integrated with the admission of four black students.[137] The integration, while tense, occurred with relative peace and was dubbed "the day nothing happened" in the local press.[138] In 1960, the Cherrydale sit-ins organized by the Nonviolent Action Group at Howard University resulted in the desegregation of Arlington businesses,[139] and with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, de jure racial housing discrimination in Arlington was officially outlawed.[140]

Arrival of Metrorail through present

[edit]Arlington County experienced decelerated population growth starting in 1960 as a result of continued migration of residents out to newer suburbs in Fairfax County and Montgomery County; between 1970 and 1980, Arlington lost 21,865 residents.[141] Factors involved in this population shift included new transportation infrastructure that made commuting from more distant communities possible, as well as white flight following the racial integration of Arlington's school system.[142] This change caused its commercial districts, which were also facing competitive pressure from suburban malls, to enter a period of decline.[143]

To revitalize these struggling neighborhoods, the Arlington County government sought to leverage the planned Washington Metro system, which was originally meant to follow the future Interstate 66 freeway.[141] Government planners were otherwise intending to use the provisions under the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act to build a freeway network in Arlington to address growing issues with traffic, which while potentially enabling easier commutes into Washington from outer suburbs, presented concerns about destructive highway construction to Arlington's residents.[141] The County Board also desired to diversify Arlington's economy away from the federal government by attracting more commercial activity.[144] This was reflected in the transformation of Rosslyn, where 19 skyscrapers were completed by 1967.[144]

After extended negotiations, the County Board convinced the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority to run the Orange Line between Rosslyn and Ballston. Residents in this area pushed back based on anticipate high-rise development surrounding the Metro stations.[141] This drove the County Board to adopt its "Bull's Eye" planning model, where higher density development would be concentrated within a walkable distance from the planned Metro stations while maintaining pre-existing single-family zoning beyond a half-mile radius.[141] Both the Orange and Blue Lines were operational by 1979.[141]

As a consequence of reduced rents caused by Orange Line construction, Clarendon became a Vietnamese enclave as refugees migrated to Arlington from Southeast Asia in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.[145] Known by names like "Little Saigon", Clarendon was one of the largest Southeast Asian commercial centers on the East Coast into the 1980s.[146][147] Increased rents and redevelopment following the opening of the Metro in 1979 eventually displaced almost all of Clarendon's Vietnamese businesses by the 1990s;[148] many moved to the Eden Center in Falls Church, which has succeeded Little Saigon as a Vietnamese community hub.[149]

The opening of the Metro stimulated another period of rapid growth. As planned, the corridor between Rosslyn and Ballston experienced revitalization driven by mixed-used, transit-oriented development.[141] Other areas near Blue line stations, such as Pentagon City, also became urbanized with numerous office complexes and retail centers like the Pentagon City Mall that opened in 1989.[141] As a result, Arlington increasingly transitioned away from being solely a commuter suburb of Washington and towards becoming an edge city with business and commercial districts.[150]

In recent years, Arlington's highly educated workforce, proximity to Washington, and financial incentives offered by the government have encouraged multinational corporations, including Amazon and Boeing, to establish corporate headquarters in Arlington's business districts.[151] New residents, including immigrants of Asian and Hispanic background, that have arrived since the passing of the 1965 Immigration Act have substantially increased Arlington's racial and ethnic diversity, altering the county's historical white-black demographic profile.[142] Some communities, such as Arlington's historically black neighborhoods, have experienced gentrification into the 21st century, driving rising costs of living.[152]

In 2020, Arlington County pursued a missing middle housing study to evaluate solutions to ongoing issues with county's inadequate housing supply, lack of housing options, and increasing housing costs.[153] Following the completion of this study and community engagement, the County Board officially adopted the Expanded Housing Options (EHO) zoning ordinance on March 22, 2023 to allow construction of up to 6 units on lots zoned for single-family housing, with the goal of increasing Arlington's housing supply and relieving upward pressure on the cost of housing.[154] As of 2025, a successful lawsuit filed by neighborhood organizations opposed to the EHO policy has blocked the measure, which is currently moving through appeal.[155]

Geography

[edit]Arlington County is located in the Northern Virginia region and is surrounded by Fairfax County and Falls Church to the west, the city of Alexandria to the southeast, and Washington, D.C. to the northeast across the Potomac River. It occupies 25.8 square miles, mostly within borders that were defined when it was made part of the District of Columbia in 1791; Arlington's irregular southeast border developed after several annexations by Alexandria that took place in the early 20th century.

Geology and terrain

[edit]Arlington County exists on a fall line between the Appalachian Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain.[156] The fall line between these geologic provinces follows Interstate 66 between Rosslyn and Four Mile Run, and cuts south to the county border around U.S. Route 50.[156] Arlington's Piedmont terrain is characterized by highly eroded rolling hills; the county's highest prominence, Minor's Hill, is in this area and rises 451 feet above sea level.[156] The Coastal Plain is generally flat. Arlington is drained by Four Mile Run, Pimmit Run, and other small streams that all flow into the Potomac River.[156] Some of these waterways have deep valleys that have been cut by erosion.[156]

Climate

[edit]

Arlington County has a humid subtropical climate that is characterized by hot, humid summers, mild to moderately cold winters. Based on climate data captured at the National Weather Service's Reagan National Airport station, regional seasonal extremes vary from average lows of 14.3 °F (−10 °C) in January to average highs of 98.1 °F (37 °C) in July. Annual precipitation averages at 41.82 inches, with an average low of 2.86 inches in January and average high of 4.33 inches in July. Average annual snowfall is 13.7 inches, with most occurring in February.

Arlington can experience extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and blizzards. These have included Agnes in 1972, Isabel in 2003, and the 2010 "Snowmaggedon" snowstorm; both hurricanes caused severe flooding and property damage,[157][158] and the 2010 blizzard brought over 13 inches of snowfall in some areas.[159] Extreme flooding of waterways such as Four Mile Run has in the past caused extensive damage to residential neighborhoods, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s before parts of the stream were channelized by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1980s; this was a result of the county's rapid 20th century development, much of which occurred before the introduction of modern stormwater management regulations.[160] Growth in Arlington's impervious surfaces, the majority of which has been driven by redevelopment of single family homes, has continued to present challenges to the county's stormwater management.[160] Localized flooding events after intense rainfall, particularly during the summer months, have occasionally been destructive to residential neighborhoods and infrastructure. For example, a July 2019 weather event later categorized as an 150-year storm resulted in hourly rainfall rates of 7 to 9 inches, which caused Four Mile Run to rise 11 feet within an hour.[161] This has required the periodic dredging of Four Mile Run to ensure it can accommodate for 100-year storms.[162] Due to global climate change, the frequency and extremity of these occurrences has increased in recent years; this trajectory is expected to continue as the broader climate warms.[163][164]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

84 (29) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

79 (26) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.7 (19.3) |

68.1 (20.1) |

77.3 (25.2) |

86.4 (30.2) |

91.0 (32.8) |

95.7 (35.4) |

98.1 (36.7) |

96.5 (35.8) |

91.9 (33.3) |

84.5 (29.2) |

74.8 (23.8) |

67.1 (19.5) |

99.1 (37.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 44.8 (7.1) |

48.3 (9.1) |

56.5 (13.6) |

68.0 (20.0) |

76.5 (24.7) |

85.1 (29.5) |

89.6 (32.0) |

87.8 (31.0) |

80.7 (27.1) |

69.4 (20.8) |

58.2 (14.6) |

48.8 (9.3) |

67.8 (19.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.5 (3.1) |

40.0 (4.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

58.2 (14.6) |

67.2 (19.6) |

76.3 (24.6) |

81.0 (27.2) |

79.4 (26.3) |

72.4 (22.4) |

60.8 (16.0) |

49.9 (9.9) |

41.7 (5.4) |

59.3 (15.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 30.1 (−1.1) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

38.6 (3.7) |

48.4 (9.1) |

58.0 (14.4) |

67.5 (19.7) |

72.4 (22.4) |

71.0 (21.7) |

64.1 (17.8) |

52.2 (11.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

34.5 (1.4) |

50.9 (10.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.3 (−9.8) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

34.9 (1.6) |

45.5 (7.5) |

55.7 (13.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

51.3 (10.7) |

38.7 (3.7) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

12.3 (−10.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

4 (−16) |

15 (−9) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

49 (9) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

11 (−12) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.86 (73) |

2.62 (67) |

3.50 (89) |

3.21 (82) |

3.94 (100) |

4.20 (107) |

4.33 (110) |

3.25 (83) |

3.93 (100) |

3.66 (93) |

2.91 (74) |

3.41 (87) |

41.82 (1,062) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.9 (12) |

5.0 (13) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.7 (4.3) |

13.7 (35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.7 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 10.1 | 117.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.8 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 8.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62.1 | 60.5 | 58.6 | 58.0 | 64.5 | 65.8 | 66.9 | 69.3 | 69.7 | 67.4 | 64.7 | 64.1 | 64.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

52.3 (11.3) |

61.5 (16.4) |

66.0 (18.9) |

65.8 (18.8) |

59.5 (15.3) |

47.5 (8.6) |

37.0 (2.8) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

44.4 (6.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 144.6 | 151.8 | 204.0 | 228.2 | 260.5 | 283.2 | 280.5 | 263.1 | 225.0 | 203.6 | 150.2 | 133.0 | 2,527.7 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 48 | 50 | 55 | 57 | 59 | 64 | 62 | 62 | 60 | 59 | 50 | 45 | 57 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961−1990)[166][167][168] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[169] | |||||||||||||

Urban landscape

[edit]

Since the opening of Metro service in the 1970s, Arlington County has become heavily urbanized; the local government has actively encouraged this via its smart growth, "Bull's Eye" urban planning model, where high density, mixed-use development is promoted within walking distance of Metro stations.[170] Adopted in the county's General Land Use Plan (GLUP) since 1975, the impact of this policy is evident in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor along the Orange and Silver lines and in the Jefferson-Davis Metro corridor along the Blue and Yellow Lines.[170][171] County planners have termed neighborhoods within the corridors as "urban villages", where each is intended to have unique amenities and characteristics.[171] These areas are rated highly for their walkability, access to public transit, and environmental sustainability, which align with design principles formulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1996.[170] Arlington's approach to urban planning has been recognized by several organizations, including the EPA, which awarded Arlington with its National Award for Smart Growth Achievement for Overall Excellence in Smart Growth in 2002,[172] and the American Planning Association, which awarded Arlington's GLUP with its National Planning Achievement Gold Award for Implementation in 2017.[173]

Outside of its urban districts, Arlington is mostly residential and suburban in character; single-family homes consisted of around 75% of its total land area in 2023.[174] Garden apartment complexes, which were built most prolifically between the New Deal era and the post-war period, exist throughout the county.[175] Several major arterial roads and highways, including Interstate 395, Interstate 66, U.S. Route 50, and U.S. Route 1 run through Arlington and connect it with the broader Washington metropolitan area.[176]

Ecology

[edit]Arlington's urbanization during the 20th century greatly impacted its local ecosystem, with many of its natural stream, wetland, and forest environments being buried, reclaimed, or removed to facilitate development; a 2011 study found that only around 738 acres of land, or 4.4% of the total land area in the county, qualified as "historical natural areas".[177] Animals that have adapted well to these conditions, including raccoons and red foxes, are abundant.[178] White-tailed deer, which were mostly eradicated from Virginia by 1900, have rebounded significantly in Arlington since reintroduction and conservation programs were instituted statewide beginning in the 1940s;[179] the county is working to develop a plan to actively manage deer to address concerns about overpopulation.[180] Around half of plants found in the county are non-native; invasive species, including numerous varieties of vine such as English Ivy and Kudzu, have been documented in Arlington.[181]

Arlington has attempted to address its environmental degradation, particularly in its watershed,[182] which has been partially restored over the past several decades to improve local water quality and provide habitats for local wildlife.[183] Past projects have included the installation of living shorelines populated with native plants, removal of invasive vegetation along the lower Four Mile Run, and the conversion of stormwater catchment ponds into wetland habitats.[184][185] These projects have provided enhanced habitats for Arlington's many native mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects.[186] Native fish that inhabit Arlington's waterways include American eel, Eastern blacknose dace, and White sucker; invasive species like snakehead and carp are also present.[187] The county government actively monitors the water quality and ecosystem of its watershed via a series of stream monitoring stations.[188]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 5,949 | — | |

| 1810 | 8,552 | 43.8% | |

| 1820 | 9,703 | 13.5% | |

| 1830 | 9,573 | −1.3% | |

| 1840 | 9,967 | 4.1% | |

| 1850 | 10,008 | 0.4% | |

| 1860 | 12,652 | 26.4% | |

| 1870 | 16,755 | 32.4% | |

| 1880 | 17,546 | 4.7% | |

| 1890 | 18,597 | 6.0% | |

| 1900 | 6,430 | −65.4% | |

| 1910 | 10,231 | 59.1% | |

| 1920 | 16,040 | 56.8% | |

| 1930 | 26,615 | 65.9% | |

| 1940 | 57,040 | 114.3% | |

| 1950 | 135,449 | 137.5% | |

| 1960 | 163,401 | 20.6% | |

| 1970 | 174,284 | 6.7% | |

| 1980 | 152,599 | −12.4% | |

| 1990 | 170,936 | 12.0% | |

| 2000 | 189,453 | 10.8% | |

| 2010 | 207,627 | 9.6% | |

| 2020 | 238,643 | 14.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[189] 1790-1960[190] 1900-1990[191] 1990-2000[192] 2010-2020[193] 2010[194] 2020[195] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2010[194] | Pop 2020[195] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 132,961 | 139,653 | 64.04% | 58.52% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 17,088 | 20,330 | 8.23% | 8.52% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 394 | 258 | 0.19% | 0.11% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 19,762 | 27,235 | 9.52% | 11.41% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 133 | 118 | 0.06% | 0.05% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 611 | 1,491 | 0.29% | 0.62% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 5,296 | 12,196 | 2.55% | 5.11% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 31,382 | 37,362 | 15.11% | 15.66% |

| Total | 207,627 | 238,643 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census,[196] there were 207,627 people, 98,050 households, and 41,607 families residing in Arlington. The population density was 8,853 people per square mile, the second highest of any county in Virginia.

According to the US Census, the racial makeup of the county in 2012 was 63.8% Non-Hispanic white, 8.9% Non-Hispanic Black or African American, 0.8% Non-Hispanic Native American, 9.9% Non-Hispanic Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.29% Non-Hispanic other races, 3.0% Non-Hispanics reporting two or more races. 15.4% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race (3.4% Salvadoran, 2.0% Bolivian, 1.7% Mexican, 1.5% Guatemalan, 0.8% Puerto Rican, 0.7% Peruvian, 0.6% Colombian). 28% of Arlington residents were foreign-born as of 2000.

There were 86,352 households, out of which 19.30% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.30% were married couples living together, 7.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.50% were non-families. 40.80% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.15 and the average family size was 2.96.

Families headed by single parents were the lowest in the DC area, under 6%, as estimated by the Census Bureau for the years 2006–2008. For the same years, the percentage of people estimated to be living alone was the third highest in the DC area, at 45%.[197] In 2009, Arlington was highest in the Washington DC Metropolitan area for the percentage of people who were single – 70.9%. 14.3% were married. 14.8% had families.[198] In 2014 Arlington had the 2nd highest concentration of roommates after San Francisco among the 50 largest U.S. cities.[199]

According to a 2007 estimate, the median income for a household in the county was $94,876, and the median income for a family was $127,179.[200] Males had a median income of $51,011 versus $41,552 for females. The per capita income for the county was $37,706. About 5.00% of families and 7.80% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.10% of those under age 18 and 7.00% of those age 65 or over.

The age distribution was 16.50% under 18, 10.40% from 18 to 24, 42.40% from 25 to 44, 21.30% from 45 to 64, and 9.40% who were 65 or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.70 males.

CNN Money ranked Arlington as the most educated city in 2006 with 35.7% of residents having held graduate degrees. Along with five other counties in Northern Virginia, Arlington ranked among the twenty American counties with the highest median household income in 2006.[201] In 2009, the county was second in the nation (after nearby Loudoun County) for the percentage of people ages 25–34 earning over $100,000 annually (8.82% of the population).[198][202] In September 2012, CNN Money ranked Arlington fourth in the country in its listing of "Best Places for the Rich and Single."[203]

In 2008, 20.3% of the population did not have medical health insurance.[204] In 2010, AIDS prevalence was 341.5 per 100,000 population. This was eight times the rate of nearby Loudoun County and one-quarter the rate of the District of Columbia.[205]

Crime statistics for 2009 included the report of 2 homicides, 15 forcible rapes, 149 robberies, 145 incidents of or aggravated assault, 319 burglaries, 4,140 incidents of larceny, and 297 reports of vehicle theft. This was a reduction in all categories from the previous year.[206]

According to a 2016 study by Bankrate.com, Arlington is the best place to retire, with nearby Alexandria coming in at second place. Criteria of the study included cost of living, rates of violent and property crimes, walkability, health care quality, state and local tax rates, weather, local culture and well-being for senior citizens.[207]

2023 marked the sixth consecutive year that the American College of Sports Medicine named Arlington the "Fittest City in America" in their annual Fitness Index.[208] Arlington topped the list of 100 cities in both the Personal and the Community & Environment Health metrics.

Government and politics

[edit]Local government

[edit]| Position | Name | Party | First elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | Takis Karatonis[209] | Democratic | 2020 | |

| Vice-chair | Matt de Ferranti[210] | Democratic | 2018 | |

| Member | Maureen Coffey[211] | Democratic | 2023 | |

| Member | Susan Cunningham[212] | Democratic | 2023 | |

| Member | JD Spain Sr.[213] | Democratic | 2024 | |

For the last two decades, Arlington has been a Democratic stronghold at nearly all levels of government.[214] However, during a special election in April 2014, a Republican running as an independent, John Vihstadt, captured a County Board seat, defeating Democrat Alan Howze 57% to 41%; he became the first non-Democratic board member in fifteen years.[215] This was in large part a voter response to plans to raise property taxes to fund several large projects, including a streetcar and an aquatics center. County Board Member Libby Garvey, in April 2014, resigned from the Arlington Democratic Committee after supporting Vihstadt's campaign over Howze.[216] Eight months later, in November's general election, Vihstadt won a full term; winning by 56% to 44%.[217] This is the first time since 1983 that a non-Democrat won a County Board general election.[218] In 2018, without the controversial streetcar issue to bolster his campaign, Vihstadt lost.[219]

The county is governed by a five-person County Board; members are elected at-large on staggered four-year terms. They appoint a county manager, who is the chief executive of the County Government. Like most Virginia counties, Arlington has five elected constitutional officers: a clerk of court, a commissioner of revenue, a commonwealth's attorney, a sheriff, and a treasurer. The budget for the fiscal year 2009 was $1.177 billion.[220]

| Position | Name | Party | First elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clerk of the Circuit Court | Paul Ferguson[221] | Democratic | 2007 | |

| Commissioner of Revenue | Ingrid Morroy[222] | Democratic | 2003 | |

| Commonwealth's Attorney | Parisa Dehghani-Tafti[223] | Democratic | 2019 | |

| Sheriff | Beth Arthur[224] | Democratic | 2000 | |

| Treasurer | Carla de la Pava[225] | Democratic | 2014 | |

Incorporation

[edit]Under Virginia law, the only municipalities that may be contained within counties are incorporated towns; incorporated cities are independent of any county. Arlington, despite its population density and largely urban character, is wholly unincorporated with no towns inside its borders. In the 1920s, a group of citizens petitioned the state courts to incorporate the Clarendon neighborhood as a town, but this was rejected; the Supreme Court of Virginia held, in Bennett v. Garrett (1922), that Arlington constituted a "continuous, contiguous, and homogeneous community" that should not be subdivided through incorporation.[226]

Current state law would prohibit the incorporation of any towns within the county because the county's population density exceeds 200 persons per square mile.[227] In 2017, then-county board chairman Jay Fisette suggested that the county as a whole should incorporate as an independent city.[228]

State and federal elections

[edit]In 2009, Republican Attorney General Bob McDonnell won Virginia by a 59% to 41% margin, but Arlington voted 66% to 34% for Democratic State Senator Creigh Deeds.[229] The voter turnout was 42.78%.[230]

Arlington elects four members of the Virginia House of Delegates and two members of the Virginia State Senate. State Senators are elected for four-year terms, while Delegates are elected for two-year terms.

In the Virginia State Senate, Arlington is split between the 30th, 31st, and 32nd districts, represented by Adam Ebbin, Barbara Favola, and Janet Howell, respectively. In the Virginia House of Delegates, Arlington is divided between the 45th, 47th, 48th, and 49th districts, represented by Mark Levine, Patrick Hope, Rip Sullivan, and Alfonso Lopez, respectively. All are Democrats.

Arlington is part of Virginia's 8th congressional district, represented by Democrat Don Beyer.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 25,223 | 19.47% | 100,446 | 77.53% | 3,892 | 3.00% |

| 2020 | 22,318 | 17.08% | 105,344 | 80.60% | 3,037 | 2.32% |

| 2016 | 20,186 | 16.64% | 92,016 | 75.83% | 9,137 | 7.53% |

| 2012 | 34,474 | 29.31% | 81,269 | 69.10% | 1,865 | 1.59% |

| 2008 | 29,876 | 27.12% | 78,994 | 71.71% | 1,283 | 1.16% |

| 2004 | 29,635 | 31.31% | 63,987 | 67.60% | 1,028 | 1.09% |

| 2000 | 28,555 | 34.17% | 50,260 | 60.15% | 4,744 | 5.68% |

| 1996 | 26,106 | 34.63% | 45,573 | 60.46% | 3,697 | 4.90% |

| 1992 | 26,376 | 31.94% | 47,756 | 57.83% | 8,452 | 10.23% |

| 1988 | 34,191 | 45.37% | 40,314 | 53.49% | 860 | 1.14% |

| 1984 | 34,848 | 48.24% | 37,031 | 51.26% | 363 | 0.50% |

| 1980 | 30,854 | 46.15% | 26,502 | 39.64% | 9,505 | 14.22% |

| 1976 | 30,972 | 47.95% | 32,536 | 50.37% | 1,091 | 1.69% |

| 1972 | 39,406 | 59.36% | 25,877 | 38.98% | 1,100 | 1.66% |

| 1968 | 28,163 | 45.92% | 26,107 | 42.57% | 7,056 | 11.51% |

| 1964 | 20,485 | 37.68% | 33,567 | 61.75% | 311 | 0.57% |

| 1960 | 23,632 | 51.40% | 22,095 | 48.06% | 250 | 0.54% |

| 1956 | 21,868 | 55.05% | 16,674 | 41.97% | 1,183 | 2.98% |

| 1952 | 22,158 | 60.91% | 14,032 | 38.57% | 190 | 0.52% |

| 1948 | 10,774 | 53.57% | 7,798 | 38.77% | 1,539 | 7.65% |

| 1944 | 8,317 | 53.66% | 7,122 | 45.95% | 60 | 0.39% |

| 1940 | 4,365 | 44.26% | 5,440 | 55.16% | 57 | 0.58% |

| 1936 | 2,825 | 36.06% | 4,971 | 63.45% | 39 | 0.50% |

| 1932 | 2,806 | 45.01% | 3,285 | 52.69% | 143 | 2.29% |

| 1928 | 4,274 | 74.75% | 1,444 | 25.25% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 1,307 | 44.74% | 1,209 | 41.39% | 405 | 13.87% |

| 1920 | 997 | 53.32% | 835 | 44.65% | 38 | 2.03% |

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 72.6% 53,021 | 26.3% 19,200 |

| 2008 | 76.0% 82,119 | 22.4% 24,232 |

| 2012 | 71.4% 82,689 | 28.3% 32,807 |

| 2014 | 70.5% 47,709 | 27.0% 18,239 |

| 2018 | 81.6% 87,258 | 15.4% 16,495 |

| 2020 | 79.4% 102,880 | 20.5% 26,590 |

| 2024 | 78.5% 100,725 | 21.2% 27,269 |

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 63.3% 32,736 | 36.2% 18,719 |

| 1997 | 62.0% 30,736 | 36.8% 18,252 |

| 2001 | 68.3% 35,990 | 30.8% 16,214 |

| 2005 | 74.3% 42,319 | 23.9% 13,631 |

| 2009 | 65.5% 36,949 | 34.3% 19,325 |

| 2013 | 71.6% 48,346 | 22.2% 14,978 |

| 2017 | 79.9% 68,093 | 19.1% 16,268 |

| 2021 | 76.7% 73,013 | 22.6% 21,548 |

The U.S. Postal Services designates Zip Codes starting with "222" for exclusive use in Arlington County. However, federal institutions, like Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and The Pentagon use Washington, D.C. Zip Codes.

Economy

[edit]

Arlington has consistently had the lowest unemployment rate of any jurisdiction in Virginia.[234] The unemployment rate in Arlington was 1.9% in July 2023.[235] 60% of office space in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor is leased to government agencies and government contractors.[236] There were an estimated 205,300 jobs in the county in 2008. About 28.7% of these were with the federal, state or local government; 19.1% technical and professional; 28.9% accommodation, food and other services.[237]

In October 2008, BusinessWeek ranked Arlington as the safest city in which to weather a recession, with a 49.4% share of jobs in "strong industries".[238] In October 2009, during the Great Recession, the unemployment in the county reached 4.2%. This was the lowest in the state, which averaged 6.6% for the same time period, and among the lowest in the nation, which averaged 9.5% for the same time.[239]

In 2021, there were an estimated 119,447 housing units in the county.[240] In 2010, there were an estimated 90,842 residences in the county.[241] In March 2024, the median home cost $717,500 and the average cost $881,925.[242] 4,721 houses, about 10% of all stand-alone homes, were worth $1 million or more. By comparison, in 2000, the median single family home price was $262,400. About 123 homes were worth $1 million or more.[243]

In 2010, 0.9% of the homes were in foreclosure. This was the lowest rate in the DC area.[244]

14% of the nearly 150,000 people working in Arlington live in the county, while 86% commute in, with 27% commuting from Fairfax County. An additional 90,000 people commute out for work, with 42% commuting to DC, and 29% commuting to Fairfax County.[245]

Federal government

[edit]A number of federal agencies are headquartered in Arlington, including the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, American Battle Monuments Commission, DARPA, Diplomatic Security Service, Drug Enforcement Administration, Foreign Service Institute, the DHS National Protection and Programs Directorate, Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, Office of Naval Research, Transportation Security Administration, United States Department of Defense, United States Marshals Service, the United States Trade and Development Agency, and the U.S. AbilityOne Commission.

Companies and organizations

[edit]

Companies headquartered in Arlington include Amazon (its second headquarters), AES, Axios, Axios HQ, Alcalde and Fay, Arlington Asset Investment, AvalonBay Communities, Bloomberg Industry Group, CACI, Graham Holdings, Naviance, Rosetta Stone, Save America, and Nestlé USA. Boeing announced on May 5, 2022, that it would be moving its global headquarters to Arlington after more than 20 years in Chicago.[246] On June 7, 2022, RTX Corporation (formerly Raytheon) announced its global headquarters relocation to Arlington.[247] On February 13, 2024, CoStar Group announced the move of their global headquarters to Arlington after more than 10 years in DC.[248] Arlington is also the location of Washington, D.C. area regional offices for several consulting firms and is the global headquarters of many aerospace manufacturing and defense industry companies.[3]

Organizations located here include the American Institute in Taiwan, Army Emergency Relief, The Conservation Fund, Conservation International, the Consumer Electronics Association, The Fellowship, the Feminist Majority Foundation, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, The Nature Conservancy, the Navy-Marine Corps Relief Society, the Public Broadcasting Service, United Service Organizations, and the US-Taiwan Business Council.

Arlington also has an annex of the South Korean embassy.[249]

Media organisations based in Arlington

[edit]Politico, a political focused digital based newspaper is based in Arlington.[250]

Axios, an American news website, founded by former Politico employees, focused on multiple subjects, in particular the collision between Technology and other subjects.[251][252]

Largest employers

[edit]

According to the county's 2023 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[253] the top employers in the county are:

| # | Employer |

|---|---|

| 1 | Federal government |

| 2 | Local government & schools |

| 3 | Amazon |

| 4 | Deloitte |

| 5 | Accenture |

| 6 | Virginia Hospital Center |

| 7 | Lidl |

| 8 | Bloomberg BNA |

| 9 | Nestlé |

| 10 | Booz Allen Hamilton |

| 11 | Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority |

| 12 | Politico |

| 13 | PBS |

| 14 | Marymount University |

| 15 | CNA |

| 16 | Boeing |

| 17 | NRECA |

| 18 | RAND Corporation |

| 19 | AECOM |

| 20 | Mastercard |

Entrepreneurship

[edit]Arlington has been recognized as a strong incubator for start-up businesses, with a number of public/private incubators and resources dedicated to fostering entrepreneurship in the county.[254]

Landmarks

[edit]

Arlington National Cemetery

[edit]Arlington National Cemetery is an American military cemetery established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's home, Arlington House (also known as the Custis-Lee Mansion). It is directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., north of the Pentagon. With around 400,000 graves covering 639 acres, Arlington National Cemetery is the second-largest national cemetery in the United States.[255]

Arlington House was named after the Custis family's homestead on Virginia's Eastern Shore. It is associated with the families of Washington, Custis, and Lee. Begun in 1802 and completed in 1817, it was built by George Washington Parke Custis. After his father died, young Custis was raised by his grandmother and her second husband, the first US President George Washington, at Mount Vernon. Custis, a far-sighted agricultural pioneer, painter, playwright, and orator, was interested in perpetuating the memory and principles of George Washington. His house became a "treasury" of Washington heirlooms.[256]

In 1804, Custis married Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Their only child to survive infancy was Mary Anna Randolph Custis, born in 1808. Young Robert E. Lee, whose mother was a cousin of Mrs. Custis, frequently visited Arlington. Two years after graduating from West Point, Lieutenant Lee married Mary Custis at Arlington on June 30, 1831. For 30 years, Arlington House was home to the Lees. They spent much of their married life traveling between U.S. Army duty stations and Arlington, where six of their seven children were born. They shared this home with Mary's parents, the Custis family.[257]

When George Washington Parke Custis died in 1857, he left the Arlington estate to Mrs. Lee for her lifetime and afterward to the Lees' eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee.[258]

After the secession of Virginia towards the beginning of the Civil War, Mary Custis and Robert E. Lee left the estate permanently. Citing a failure to pay taxes, the U.S. government confiscated Arlington House and 200 acres (81 ha) of property from the Lees on January 11, 1864. On June 15, 1864, the U.S. government and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton designated the grounds as a military cemetery. In 1882, after many years in the lower courts, the matter of the ownership of Arlington House and its land was brought before the United States Supreme Court by George Washington Custis Lee. The Court decided that the property rightfully belonged to the Lee family. Shortly, the United States Congress appropriated the sum of $150,000 for the purchase of the property from the Lee family in March 1883.[258]

Veterans from all the nation's wars are buried in the cemetery, from the American Revolution through the military actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. Pre-Civil War dead were re-interred after 1900.[citation needed]

The Tomb of the Unknowns, also known as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, stands atop a hill overlooking Washington, DC. President John F. Kennedy is buried in Arlington National Cemetery with his wife Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and some of their children. His grave is marked with an eternal flame. His brothers, Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Edward M. Kennedy, are also buried nearby. William Howard Taft, who was also a Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, is the only other President buried at Arlington.

Other frequently visited sites near the cemetery are the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial, commonly known as the Iwo Jima Memorial, the U.S. Air Force Memorial, the Women in Military Service for America Memorial, the Netherlands Carillon and the U.S. Army's Fort Myer.[citation needed]

The Pentagon

[edit]

The Pentagon in Arlington is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense. It was dedicated on January 15, 1943, and it is the world's second-largest office building. Although it is located in Arlington County, the United States Postal Service requires that "Washington, D.C." be used as the place name in mail addressed to the six ZIP codes assigned to The Pentagon.[259]

The building is pentagon-shaped and houses about 24,000 military and civilian employees and about 3,000 non-defense support personnel. It has five floors and each floor has five ring corridors. The Pentagon's principal law enforcement arm is the United States Pentagon Police, the agency that protects the Pentagon and various other DoD jurisdictions throughout the National Capital Region.[260]

Built during World War II, the Pentagon is the world's largest low-rise office building with 17.5 miles (28.2 km) of corridors, yet it takes only seven minutes to walk between its furthest two points.[261]

It was built from 689,000 short tons (625,000 t) of sand and gravel dredged from the nearby Potomac River[261] that were processed into 435,000 cubic yards (330,000 m3) of concrete and molded into the pentagon shape. Very little steel was used in its design due to the needs of the war effort.[262]

The open-air central plaza in the Pentagon is the world's largest "no-salute, no-cover" area (where U.S. servicemembers need not wear hats nor salute). Before being torn down in 2006, a hot dog stand occupied Ground Zero at the center of the courtyard. The food stand was reportedly a Soviet target during the Cold War due to the legend of a secret bunker entrance hidden beneath it.[263]

During World War II, the earliest portion of the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway was built in Arlington in conjunction with the parking and traffic plan for the Pentagon. Land for parking and roads was acquired by the exercise of eminent domain over the African-American neighborhood of Queen City, in East Arlington, displacing hundred of Black families.[264][265] This early freeway, opened in 1943 and completed to Woodbridge, in 1952, is now part of I-395.[citation needed]

The Pentagon Memorial, commemorating victims in the September 11 attacks, is located outside of the Pentagon and is a major tourist attraction.

Transportation

[edit]

Streets and roads

[edit]Arlington forms part of the region's core transportation network. The county is traversed by two interstate highways: I-66 in the northern part of the county and I-395 in the eastern part, both with HOV lanes or restrictions. In addition, the county is served by the George Washington Memorial Parkway. In total, Arlington County maintains 376 miles (605 km) of roads.[266]

The street names in Arlington generally follow a unified countywide convention. The north–south streets are generally alphabetical, starting with one-syllable names, then two-, three- and four-syllable names. The first alphabetical street is Ball Street. The last is Arizona. Many east–west streets are numbered. Route 50 divides Arlington County. Streets are generally labeled North above Route 50, and South below.

Arlington has more than 100 miles (160 km) of on-street and paved off-road bicycle trails.[267] Off-road trails travel along the Potomac River or its tributaries, abandoned railroad beds, or major highways, including Four Mile Run Trail that travels the length of the county; the Custis Trail, which runs the width of the county from Rosslyn; the Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Trail (W&OD Trail) that travels 45 miles (72 km) from the Shirlington neighborhood out to western Loudoun County; and the Mount Vernon Trail that runs for 17 miles (27 km) along the Potomac, continuing through Alexandria to Mount Vernon.

Public transport

[edit]

Forty percent of Virginia's transit trips begin or end in Arlington, with the vast majority originating from Washington Metro rail stations.[268]

Arlington is served by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA or Metro), the regional transit agency covering parts of Northern Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. Arlington has stations on the Blue, Orange, Silver and Yellow lines of the Washington Metro rail system. Arlington is also served by WMATA's regional Metrobus service. This includes Metroway, the first bus rapid transit (BRT) in the D.C. area, a joint project between WMATA, Arlington County, and Alexandria, with wait times similar to those of Metro trains. Metroway began service in August 2014.[269]

Arlington also operates its own county bus system, Arlington Transit (ART), which supplements Metrobus service with in-county routes and connections to the rail system.[270]

The Virginia Railway Express commuter rail system has one station in Arlington County, at the Crystal City station. Public bus services operated by other Northern Virginia jurisdictions include some stops in Arlington, most commonly at the Pentagon. These services include DASH (Alexandria Transit Company), Fairfax Connector, PRTC OmniRide (Potomac and Rappahannock Transportation Commission), and the Loudoun County Commuter Bus.[271][272]

Other

[edit]

Capital Bikeshare, a bicycle sharing system, began operations in September 2010 with 14 rental locations primarily around Washington Metro stations throughout the county.[273]

Arlington County is home to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, which provides domestic air services to the Washington, D.C., area. In 2009, Condé Nast Traveler readers voted it the country's best airport.[274] Nearby international airports are Washington Dulles International Airport, located in Fairfax and Loudoun counties in Virginia, and Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, located in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

In 2007, the county authorized EnviroCAB, a new taxi company, to operate exclusively with a hybrid-electric fleet of 50 vehicles and also issued permits for existing companies to add 35 hybrid cabs to their fleets. As operations began in 2008, EnvironCab became the first all-hybrid taxicab fleet in the United States, and the company not only offset the emissions generated by its fleet of hybrids, but also the equivalent emissions of 100 non-hybrid taxis in service in the metropolitan area.[275][276] The green taxi expansion was part of a county campaign known as Fresh AIRE, or Arlington Initiative to Reduce Emissions, that aimed to cut production of greenhouse gases from county buildings and vehicles by 10 percent by 2012.[275] Arlington has a higher than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 13.4 percent of Arlington households lacked a car, and dropped slightly to 12.7 percent in 2016. The national average is 8.7 percent in 2016. Arlington averaged 1.40 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[277]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary education

[edit]

Arlington Public Schools operates the county's public K-12 education system of 22 elementary schools, six middle schools, Dorothy Hamm Middle School, Gunston Middle School, Kenmore Middle School, Swanson Middle School, Thomas Jefferson Middle School, and Williamsburg Middle School, and three public high schools, Wakefield High School, Washington-Liberty High School, and Yorktown High School. H-B Woodlawn and Arlington Tech are alternative public schools. Arlington County spends about half of its local revenues on education. For the FY2013 budget, 83 percent of funding was from local revenues, and 12 percent from the state. Per pupil expenditures are expected [when?] to average $18,700, well above its neighbors, Fairfax County ($13,600) and Montgomery County ($14,900).[279]

Arlington has an elected five-person school board whose members are elected to four-year terms. Virginia law does not permit political parties to place school board candidates on the ballot.[280]

| Position | Name | First Election | Next Election |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | Reid Goldstein | 2015 | 2023 |

| Vice Chair | Cristina Diaz-Torres | 2020 | 2024 |

| Member | David Priddy | 2020 | 2024 |

| Member | Mary Kadera | 2021 | 2025 |

| Member | Bethany Sutton | 2022 | 2026 |