Hostile abdomen

This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (May 2025) |

| Hostile abdomen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Surgical interventions involved in the management of hostile abdomen | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms |

|

| Complications |

|

| Causes |

|

| Diagnostic method | |

| Prevention | |

| Medication | |

Hostile abdomen, a complex clinical condition, is characterized by excessive fibrous adhesions and scarring in the abdominal cavity, often resulting from previous surgeries or inflammatory disorders.[3][5] Hostile abdomen can lead to significant complications such as chronic abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, and prolonged recovery times following surgical interventions.[2][1][6] Common symptoms include limited abdominal wall compliance and fragile intestinal tissue, which may contribute to complications.[3] Short-term complications may arise shortly after surgery, including intra-abdominal infections and bowel fistulas, while long-term issues can involve chronic bowel obstruction and incisional hernia.[4] The diagnosis for hostile abdomen typically requires a combination of medical history, physical examination, and imaging techniques, with intra-operative assessments often confirming the presence of adhesions.[5][14]

Management strategies aim to reduce adhesion formation and address complications through both non-surgical and surgical approaches.[3][6][13] A thorough understanding of the underlying causes, including organic and iatrogenic factors, is essential for prevention and management of hostile abdomen.[7][8]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Common symptoms and complications associated with a hostile abdomen include limited abdominal wall compliance and peritoneal fibrosis or thickening.[3] These conditions can lead to significant issues. For instance, adhesions from previous surgeries can lead to tension or obstruction, resulting in chronic or recurrent abdominal pain.[1] Additionally, intestinal tissue may appear fragile and delicate, often scarred and thickened into a solid mass.[5]

Short-term complications typically arise within days to weeks of post-surgery.[5] One major issue is intra-abdominal sepsis, which can significantly prolong recovery.[5][6] Moreover, bowel obstruction may arise from adhesions, requiring immediate intervention.[5][2] Another serious concern is fluid buildup at the surgical connections between segments of the bowel.[5][6] Furthermore, bowel fistulas, or abnormal connections that form between different parts of the bowel, are also common short-term complications that require prolonged treatment and increase hospital stays.[4] Unintentional enterotomy, or accidental cutting into the bowel during surgery, poses an increased acute risk.[2] These complications collectively increase surgical risk, prolong operating times, and exacerbate blood loss.[6]

Long-term complications may include bowel obstruction, persistent sepsis, incisional hernia, and short bowel syndrome due to significant bowel resection.[5] Individuals with a hostile abdomen frequently experience a longer and more complicated recovery process compared to standard cases.[5][6] Overall, while some individuals may remain asymptomatic, others can experience severe symptoms such as bowel strangulation or ischemia.[5]

Causes

[edit]The causes of hostile abdomen can be broadly categorised into organic and iatrogenic factors. Organic causes primarily involve conditions that directly affect the peritoneum, while iatrogenic causes are primarily related to medical interventions.

Organic causes

[edit]Peritoneal injury/ inflammation

[edit]

Peritoneal injury and inflammation are prevalent in individuals with peritoneal inflammatory disorders such as peritonitis and Crohn's disease.[7] Inflammatory responses may trigger excessive fibrin disposition, increasing the risk of hostile abdomen.[15]

Intra-abdominal infections

[edit]

Intra-abdominal infections in conditions like acute appendicitis and abdominal tuberculosis significantly contribute to hostile abdomen.[5][6] These infections triggers the release of Inflammatory cytokines and increase vascular permeability, leading to fibrin deposition that exacerbates the risk of developing hostile abdomen.[16]

Endometriosis

[edit]

Endometriosis involves the growth of tissue similar to the endometrium outside the uterus, causing pelvic pain and inflammation.[5] This abnormal tissue growth results in scarred fibrotic tissues and smooth muscle proliferation near lesions, leading to peritoneal adhesions that complicate surgical procedures.[17] Common injury sites due to endometriosis include the ovarian cyst wall, rectum, and vagina.[18][19]

Iatrogenic causes

[edit]Surgery-induced adhesions

[edit]

Surgical adhesions account for over 90% of cases linked to prior surgeries.[8] Procedures such as appendicectomy and large bowel resections can cause tissue trauma, activating a healing response that forms adhesions and scar tissue.[20] The likelihood of adhesion development increases with the number of surgical interventions an individual undergoes.[21]

Radiation therapy

[edit]Radiation therapy, widely used in treating malignancies like gynecological diseases, can lead to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions and radiation-induced fibrosis.[22] Improper radiation doses or incorrect targeting of body regions can exacerbate the risk of injury, particularly in the large intestine near the cecum.[23]

Peritoneal dialysis (PD)

[edit]Peritoneal dialysis is a technique commonly used on individuals with chronic kidney disease.[24] However, it could lead to complications like infections (e.g. peritonitis) or gastrointestinal perforation.[25] These conditions accelerate adhesion formation and may result in intestinal obstruction, potentially leading to encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, which increases the risk of fibrotic tissue deposition in abdominal organs.[24]

Foreign body reactions

[edit]Foreign body reactions can be caused by surgical materials, such as mesh implants used in hernia repairs.[27] Foreign body reactions can trigger inflammation and wound-healing responses.[28] These reactions contribute to the formation of fibrotic adhesion.[28]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The pathophysiology of hostile abdomen primarily involves a chronic inflammatory response, which may be naturally occurring or induced by treatment.[29] This inflammation results in excessive production of scarred and fibrotic tissues from myofibroblasts, which is the activated form of fibroblast.[30] Consequently, normal cellular architecture in the abdominal region is replaced by dense fibrotic tissues, leading to adhesion within abdominal organs.[30]

Cytokine and chemokine signalling

[edit]Cytokines and chemokines, such as TGF-β, and interleukin like Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 have a central role in the inflammatory response.[31][32] TGF-β promotes myofibroblast differentiation and inhibiting the degradation of the extracellular matrix.[33] Moreover, Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 enhance extracellular matrix production and create a positive feedback loop that accelerating fibrotic response.[34]

Imbalance immune responses

[edit]The immune response is characterized by two main pathways: Th1 and Th2 responses.[35] Both pathways play opposing roles in fibrosis.[35] The Th1 response, mediated by interferon gamma, promotes macrophage activation and inhibit fibrosis.[30] In contrast, the Th2 response increases Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 production, driving fibrosis by myofibroblast activation.[36] Chronic inflammation leads to prolonged Th2 response, resulting in excessive extracellular matrix formation and scarring, which perpetuates the fibrotic process.[30][36]

Angiotensin

[edit]Angiotensin is a peptide hormone released during chronic inflammation, activates the Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS).[37] This hormone exacerbates inflammation and promotes fibrosis by inducing myofibroblast differentiation.[37][38] As a result, angiotensin contributes to excess tissue damage and deposition of extracellular matrix.[38]

Diagnostic method

[edit]Diagnosing hostile abdomen relies on a combination of clinical assessments and imaging techniques. While the diagnosis is often confirmed during surgery, pre-operative suspicion plays a crucial role.

Pre-operative diagnosis

[edit]Medical history

[edit]A detailed medical history is essential for diagnosing hostile abdomen.[5] This includes medical details about prior abdominal surgeries—such as the number, type, and any complications—as well as history of trauma, inflammatory bowel disease (like Crohn's disease), radiation therapy to the abdomen, and past abdominal infections or sepsis.[39] The Hostile Abdomen Index (HAI) is a tool used to stratify risk preoperatively.[9] Higher scores on the HAI correlate with an increased likelihood of hostile abdomen due to prior surgeries or complications.[9]

Physical examination

[edit]A physical examination may reveal signs of abdominal distension, tenderness, or guarding.[5] However, these signs can be subtle or absent, especially in individuals with chronic conditions.[40]

Imaging

[edit]

Imaging techniques like abdominal X-rays can reveal signs of bowel obstruction, such as air-fluid levels and enlarged intestinal loops.[14] Furthermore, a CT scan with oral contrast provides more detailed information, including bowel wall thickening, mesenteric changes, stenosis, retractile mesenteritis, and calcification in severe cases.[41] However, imaging may not reveal the full extent of adhesions or scarring due to lack of measurable indicators.[8]

Intra-operative diagnosis

[edit]

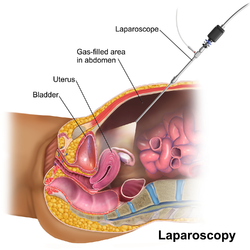

Laparoscopy

[edit]Laparoscopy involves inserting a laparoscope through small incisions to directly visualize the abdominal organs.[10] Laparoscopy allows the assessment of adhesions, inflammation, abscesses, or other abnormalities characteristic of a hostile abdomen.[11] This visual inspection provides crucial information that cannot be fully obtained from pre-operative imaging.[10][11]

Open exploration

[edit]Open exploration is performed when laparoscopy is not feasible or if significant pathology is suspected.[5] This surgical approach enables clear visualisation and manipulation of the abdominal structure.[11]

Prevention

[edit]To prevent the development of a hostile abdomen, there are three main strategies used which focus on reducing peritoneal adhesion formation.

Minimally invasive surgery

[edit]Minimally invasive surgery employs techniques such as laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgery.[42] These methods involve making small incisions to access abdominal and pelvic organs with the aid of a 3D high-resolution camera.[18] Minimally invasive surgery can reduce peritoneal trauma and the likelihood of adhesion formation.[12]

Adhesion barriers

[edit]Adhesion barrier materials, such as Seprafilm, Hyalobarrier, SprayGel are used in abdominal laparotomy surgery to prevent adhesions.[43] These materials can decrease the extent, incidence, and severity of adhesions.[12][44] Moreover, ongoing development of new barriers aim to improve their effectiveness to further mitigate risks for hostile abdomen formation.[5]

Anti-adhesion agents

[edit]Anti-adhesion agents, such as corticosteroids, can be used to reduce inflammation and prevent adhesion formation.[46] However, their therapeutic efficacy is limited, making them less common in clinical practice for hostile abdomen prevention.[12]

Management

[edit]Hostile abdomen management depends on symptom severity and complications, and are categorised into non-surgical and surgical approaches.

Non-surgical management

[edit]

Conservative management

[edit]Conservative management focuses on symptom relief.[5] This may include dietary modifications to improve digestion.[5] Additionally, pain control by analgesics[6] can help manage discomfort, while bowel-regulating agents, such as laxatives, are utilized to alleviate constipation.[48]

Adhesion prevention therapy

[edit]Adhesion prevention therapy is a developing field aimed at preventing or reducing the formation of new adhesions after surgery.[49] This therapy seeks to treat existing adhesions by inducing fibrinolysis.[49] However, the efficacy and long-term impact of these therapies are still under evaluation, highlighting the need for ongoing research.[5]

Surgical management

[edit]

Adhesiolysis

[edit]Adhesiolysis involves the surgical removal of adhesions.[13] During this procedure, the surgeon dissects the adhesions while preserving the integrity of underlying abdominal structures.[5] Advanced imaging techniques aid in a more precise and effective removal.[6]

Bowel resection

[edit]In cases where significant bowel damage has occurred, bowel resection may be necessary.[5][6] This procedure surgically removes the affected bowel segments, with the healthy ends being reconnected through anastomosis.[2] Bowel resection is a major procedure with its own set of risks and complications, and must be carefully considered before proceeding.[50]

Abdominal wall reconstruction

[edit]Abdominal wall reconstruction may be necessary when there is a significant loss of abdominal wall tissue.[5] This reconstruction may involve the use of biologic or synthetic mesh to cover the defect and provide support.[51] This approach not only restores function but also improves the overall stability of the abdominal wall.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Fatehi Hassanabad, Ali; Zarzycki, Anna N.; Jeon, Kristina; Dundas, Jameson A.; Vasanthan, Vishnu; Deniset, Justin F.; Fedak, Paul W. M. (2021-07-14). "Prevention of Post-Operative Adhesions: A Comprehensive Review of Present and Emerging Strategies". Biomolecules. 11 (7): 1027. doi:10.3390/biom11071027. ISSN 2218-273X. PMC 8301806. PMID 34356652.

- ^ a b c d e Martínez-Hoed, Jesús; Ortiz-Cubero, José Ángel; Montagné-Bonilla, Nicole; Bueno-Lledó, José A.; Pous-Serrano, Salvador (July–September 2023). "Early small bowel obstruction following abdominal wall hernia repair: Report of four cases and systematic review of the literature". International Journal of Abdominal Wall and Hernia Surgery. 6 (3): 125. doi:10.4103/ijawhs.IJAWHS_13_23. ISSN 2589-8736.

- ^ a b c d e Attard, Jo-Anne P.; MacLean, Anthony R. (2007). "Adhesive small bowel obstruction: epidemiology, biology and prevention". Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien de Chirurgie. 50 (4): 291–300. ISSN 0008-428X. PMC 2386166. PMID 17897517.

- ^ a b c Pepe, Gilda; Chiarello, Maria Michela; Bianchi, Valentina; Fico, Valeria; Altieri, Gaia; Tedesco, Silvia; Tropeano, Giuseppe; Molica, Perla; Di Grezia, Marta; Brisinda, Giuseppe (2024-02-23). "Entero-Cutaneous and Entero-Atmospheric Fistulas: Insights into Management Using Negative Pressure Wound Therapy". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13 (5): 1279. doi:10.3390/jcm13051279. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 10932196. PMID 38592102.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Lundy, Megan; Ashburn, Jean H. (2022). "Management of the Hostile Abdomen". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 35 (3): 169–176. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1740043. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 9374530. PMID 35966382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Smith, Brian P.; Adams, Raeanna C.; Doraiswamy, Vijay A.; Nagaraja, Vivek; Seamon, Mark J.; Wisler, Johathan; Cipolla, James; Sharma, Rohit; Cook, Charles H.; Gunter, Oliver L.; Stawicki, Stanislaw Pa (2010). "Review of abdominal damage control and open abdomens: focus on gastrointestinal complications". Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 19 (4): 425–435. ISSN 1842-1121. PMID 21188335.

- ^ a b c Aka, Allison A.; Wright, Jesse P.; DeBeche-Adams, Teresa (2021). "Small Bowel Obstruction". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 34 (4): 219–226. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1725204. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 8292006. PMID 34305470.

- ^ a b c d Okabayashi, Koji; Ashrafian, Hutan; Zacharakis, Emmanouil; Hasegawa, Hirotoshi; Kitagawa, Yuko; Athanasiou, Thanos; Darzi, Ara (2014-03-01). "Adhesions after abdominal surgery: a systematic review of the incidence, distribution and severity". Surgery Today. 44 (3): 405–420. doi:10.1007/s00595-013-0591-8. ISSN 1436-2813. PMID 23657643.

- ^ a b c Coco, Danilo; Leanza, Silvana (2020). "A Review on Aorta Mesenteric Bypass in Surgical Management of Mesenteric Ischemia: Indications, Techniques and Outcomes". Maedica. 15 (3): 381–390. doi:10.26574/maedica.2020.15.3.381. ISSN 1841-9038. PMC 7726511. PMID 33312256.

- ^ a b c Garry, Ray (2006-02-01). "Laparoscopic surgery". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. Gynaecological Surgery: Techniques, Training, Skills and Assessment. 20 (1): 89–104. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.10.003. ISSN 1521-6934. PMID 16373090.

- ^ a b c d Pau, Luca; Navez, Julie; Cawich, Shamir O.; Dapri, Giovanni (2021). "Laparoscopic Management of Blunt and Penetrating Abdominal Trauma: A Single-Center Experience and Review of the Literature". Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. 31 (11): 1262–1268. doi:10.1089/lap.2020.0552. ISSN 1092-6429. PMID 33428516.

- ^ a b c d e f Aref-Adib, Mehrnoosh; Phan, Timothy; Ades, Alexandre (2019). "Preventing adhesions in laparoscopic surgery: the role of anti-adhesion agents". The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 21 (3): 185–192. doi:10.1111/tog.12588. ISSN 1744-4667.

- ^ a b c Kavic, Stephen M.; Kavic, Suzanne M. (2002). "Adhesions and adhesiolysis: the role of laparoscopy". Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 6 (2): 99–109. ISSN 1086-8089. PMC 3043408. PMID 12113430.

- ^ a b Musson, Rachel E; Bickle, Ian; Vijay, Ram K P (2011-04-01). "Gas patterns on plain abdominal radiographs: a pictorial review". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 87 (1026): 274–287. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2009.082396. ISSN 0032-5473. PMID 21242574.

- ^ Liakakos, Theodoros; Thomakos, Nikolaos; Fine, Paul M.; Dervenis, Christos; Young, Ronald L. (2001-08-27). "Peritoneal Adhesions: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Significance : Recent Advances in Prevention and Management". Digestive Surgery. 18 (4): 260–273. doi:10.1159/000050149. ISSN 0253-4886. PMID 11528133.

- ^ Ärzteblatt, Deutscher Ärzteverlag GmbH, Redaktion Deutsches (2010). "Intra-abdominal Adhesions (05.11.2010)". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 107 (44): 769–775. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0769. PMC 2992017. PMID 21116396. Retrieved 2025-03-31.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rocca, Aldo; Aprea, Giovanni; Surfaro, Giuseppe; Amato, Maurizio; Giuliani, Antonio; Paccone, Marianna; Salzano, Andrea; Russo, Anna; Tafuri, Domenico; Amato, Bruno (2016-01-01). "Prevention and treatment of peritoneal adhesions in patients affected by vascular diseases following surgery: a review of the literature". Open Medicine. 11 (1): 106–114. doi:10.1515/med-2016-0021. ISSN 2391-5463. PMC 5329808. PMID 28352777.

- ^ a b Koninckx, Philippe R.; Ussia, Anastasia; Adamyan, Leila; Wattiez, Arnaud; Donnez, Jacques (2012-09-01). "Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment". Fertility and Sterility. 98 (3): 564–571. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1061. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 22938769.

- ^ Garcia Garcia, Jose Manuel; Vannuzzi, Valentina; Donati, Chiara; Bernacchioni, Caterina; Bruni, Paola; Petraglia, Felice (2023-05-01). "Endometriosis: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Leading to Fibrosis". Reproductive Sciences. 30 (5): 1453–1461. doi:10.1007/s43032-022-01083-x. ISSN 1933-7205. PMC 10160154. PMID 36289173.

- ^ Herrick, Sarah E.; Wilm, Bettina (2021-05-05). "Post-Surgical Peritoneal Scarring and Key Molecular Mechanisms". Biomolecules. 11 (5): 692. doi:10.3390/biom11050692. ISSN 2218-273X. PMC 8147932. PMID 34063089.

- ^ Menzies, D.; Ellis, H. (1990). "Intestinal obstruction from adhesions--how big is the problem?". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 72 (1): 60–63. ISSN 0035-8843. PMC 2499092. PMID 2301905.

- ^ Majeed, Hafsa; Gupta, Vikas (2025), "Adverse Effects of Radiation Therapy", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 33085406, retrieved 2025-04-02

- ^ Tabibian, N.; Swehli, E.; Boyd, A.; Umbreen, A.; Tabibian, J. H. (2017). "Abdominal adhesions: A practical review of an often overlooked entity". Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 15: 9–13. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2017.01.021. ISSN 2049-0801. PMC 5295619. PMID 28203370.

- ^ a b Andreoli, Maria Claudia Cruz; Totoli, Claudia (2020-01-13). "Peritoneal Dialysis". Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 66 (Suppl 1): s37 – s44. doi:10.1590/1806-9282.66.S1.37. ISSN 0104-4230. PMID 31939534.

- ^ Peppelenbosch, Arnoud; van Kuijk, Willy H. M.; Bouvy, Nicole D.; van der Sande, Frank M.; Tordoir, Jan H. M. (2008-10-01). "Peritoneal dialysis catheter placement technique and complications". NDT Plus. 1 (suppl_4): iv23 – iv28. doi:10.1093/ndtplus/sfn120. ISSN 1753-0784. PMC 4421142. PMID 25983982.

- ^ Gutcher, Ilona; Becher, Burkhard (2007-05-01). "APC-derived cytokines and T cell polarization in autoimmune inflammation". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (5): 1119–1127. doi:10.1172/JCI31720. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 1857272. PMID 17476341.

- ^ Pérez-Köhler, Bárbara; Bayon, Yves; Bellón, Juan Manuel (2016). "Mesh Infection and Hernia Repair: A Review". Surgical Infections. 17 (2): 124–137. doi:10.1089/sur.2015.078. ISSN 1096-2964. PMID 26654576.

- ^ a b Anderson, James M.; Rodriguez, Analiz; Chang, David T. (2008-04-01). "Foreign body reaction to biomaterials". Seminars in Immunology. Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in Tissue Engineering. 20 (2): 86–100. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. ISSN 1044-5323. PMC 2327202. PMID 18162407.

- ^ Roberts, Derek J; Leppäniemi, Ari; Tolonen, Matti; Mentula, Panu; Björck, Martin; Kirkpatrick, Andrew W; Sugrue, Michael; Pereira, Bruno M; Petersson, Ulf; Coccolini, Federico; Latifi, Rifat (2023-10-01). "The open abdomen in trauma, acute care, and vascular and endovascular surgery: comprehensive, expert, narrative review". BJS Open. 7 (5): zrad084. doi:10.1093/bjsopen/zrad084. ISSN 2474-9842. PMC 10601091. PMID 37882630.

- ^ a b c d Wynn, Ta (2008). "Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis". The Journal of Pathology. 214 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1002/path.2277. ISSN 1096-9896. PMC 2693329. PMID 18161745.

- ^ Sanjabi, Shomyseh; Oh, Soyoung A.; Li, Ming O. (2017-06-01). "Regulation of the Immune Response by TGF-β: From Conception to Autoimmunity and Infection". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 9 (6): a022236. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a022236. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 5453394. PMID 28108486.

- ^ Al-Qahtani, Arwa A.; Alhamlan, Fatimah S.; Al-Qahtani, Ahmed Ali (2024-01-04). "Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins in Infectious Diseases: A Comprehensive Review". Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 9 (1): 13. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed9010013. ISSN 2414-6366. PMC 10818686. PMID 38251210.

- ^ Yang, XiaoHong; Chen, Bo; Liu, Tao; Chen, XiaoHong. (2014-07-05). "Reversal of myofibroblast differentiation: A review". European Journal of Pharmacology. 734: 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.04.007. ISSN 0014-2999. PMID 24742377.

- ^ Borthwick, Lee A.; Wynn, Thomas A.; Fisher, Andrew J. (2013-07-01). "Cytokine mediated tissue fibrosis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. Fibrosis: Translation of basic research to human disease. 1832 (7): 1049–1060. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.09.014. ISSN 0925-4439. PMC 3787896. PMID 23046809.

- ^ a b Berger, A. (2000-08-12). "Th1 and Th2 responses: what are they?". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 321 (7258): 424. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7258.424. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 27457. PMID 10938051.

- ^ a b Deng, Lishan; Huang, Teng; Zhang, Lei (2023-02-14). "T cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: crucial but controversial". Cell Death Discovery. 9 (1): 62. doi:10.1038/s41420-023-01344-x. ISSN 2058-7716. PMC 9929223. PMID 36788232.

- ^ a b Fountain, John H.; Kaur, Jasleen; Lappin, Sarah L. (2025), "Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29261862, retrieved 2025-04-02

- ^ a b Murphy, Amanda M.; Wong, Alison L.; Bezuhly, Michael (2015-04-23). "Modulation of angiotensin II signaling in the prevention of fibrosis". Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair. 8 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s13069-015-0023-z. ISSN 1755-1536. PMC 4422447. PMID 25949522.

- ^ Thompson, Jon S. (2014-06-03). "Short Bowel Syndrome and Malabsorption - Causes and Prevention". Viszeralmedizin. 30 (3): 174–178. doi:10.1159/000363276. ISSN 1662-6664. PMC 4513821. PMID 26288591.

- ^ Zackowski, Scott W. (1998-11-01). "Chronic Recurrent Abdominal Pain". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 16 (4): 877–894. doi:10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70037-7. ISSN 0733-8627. PMID 9889744.

- ^ Sheth, Sheila; Horton, Karen M.; Garland, Melissa R.; Fishman, Elliot K. (2003). "Mesenteric Neoplasms: CT Appearances of Primary and Secondary Tumors and Differential Diagnosis". RadioGraphics. 23 (2): 457–473. doi:10.1148/rg.232025081. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 12640160.

- ^ Minig, Lucas; Achilarre, Marla Teresa; Garbi, Annalisa; Zanagnolo, Vanna (2017-03-01). "Minimally Invasive Surgery to Treat Gynecological Cancer: Conventional Laparoscopy and/or Robot-Assisted Surgery". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 27 (3): 562–574. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000925. ISSN 1048-891X. PMID 28187093.

- ^ Schaefer, Sebastian D.; Alkatout, Ibrahim; Dornhoefer, Nadja; Herrmann, Joerg; Klapdor, Ruediger; Meinhold-Heerlein, Ivo; Meszaros, Jozsef; Mustea, Alexander; Oppelt, Peter; Wallwiener, Markus; Kraemer, Bernhard (2024-08-01). "Prevention of peritoneal adhesions after gynecological surgery: a systematic review". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 310 (2): 655–672. doi:10.1007/s00404-024-07584-1. ISSN 1432-0711. PMC 11258159. PMID 38878233.

- ^ Waldron, Michael Gerard; Judge, Conor; Farina, Laura; O'Shaughnessy, Aoife; O'Halloran, Martin (2022-05-02). "Barrier materials for prevention of surgical adhesions: systematic review". BJS Open. 6 (3): zrac075. doi:10.1093/bjsopen/zrac075. ISSN 2474-9842. PMC 9167938. PMID 35661871.

- ^ Williams, Dennis M (2018). "Clinical Pharmacology of Corticosteroids". Respiratory Care. 63 (6): 655–670. doi:10.4187/respcare.06314. ISSN 0020-1324. PMID 29794202.

- ^ Dasgupta, Falguni; and Narasinga Rao, B N (1994-07-01). "Anti-adhesive therapeutics: A new class of anti-inflammatory agents". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 3 (7): 709–724. doi:10.1517/13543784.3.7.709. ISSN 1354-3784.

- ^ Queremel Milani, Daniel A.; Davis, Donald D. (2025), "Pain Management Medications", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32809527, retrieved 2025-04-02

- ^ Berbiglia, Lindsay; Zografakis, John G.; Dan, Adrian G. (2016-08-01). "Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: Surgical Technique and Perioperative Care". Surgical Clinics of North America. Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. 96 (4): 773–794. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2016.03.003. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 27473801.

- ^ a b Sajja, S B S; Schein, M (2004-06-01). "Early postoperative small bowel obstruction". British Journal of Surgery. 91 (6): 683–691. doi:10.1002/bjs.4589. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 15164435.

- ^ Maguire, Lillias Holmes; Alavi, Karim; Sudan, Ranjan; Wise, Paul E.; Kaiser, Andreas M.; Bordeianou, Liliana (2017-02-01). "Surgical Considerations in the Treatment of Small Bowel Crohn's Disease". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 21 (2): 398–411. doi:10.1007/s11605-016-3330-9. ISSN 1091-255X. PMID 27966058.

- ^ Leppäniemi, A.; Tukiainen, E. (2013-03-01). "Reconstruction of Complex Abdominal Wall Defects". Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 102 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1177/145749691310200104. ISSN 1457-4969. PMID 23628631.

- ^ Butler, Charles E.; Baumann, Donald P.; Janis, Jeffrey E.; Rosen, Michael J. (2013-12-01). "Abdominal wall reconstruction". Current Problems in Surgery. 50 (12): 557–586. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2013.08.003. ISSN 0011-3840. PMID 24231005.

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (June 2025) |