Ahmed I

| Ahmed I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Caliph Amir al-Mu'minin Kayser-i Rûm Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

Anonymous portrait of Ahmed I | |||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 22 December 1603 – 22 November 1617 | ||||

| Sword girding | 23 December 1603 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mehmed III | ||||

| Successor | Mustafa I | ||||

| Born | 18 April 1590 Manisa Palace, Manisa, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 22 November 1617 (aged 27) Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Sultan Ahmed Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey | ||||

| Consorts | Mahfiruz Hatun Kösem Sultan[1] | ||||

| Issue Among others | Osman II Şehzade Mehmed Ayşe Sultan Gevherhan Sultan Fatma Sultan Hanzade Sultan Murad IV Şehzade Bayezid Şehzade Süleyman Şehzade Kasım Atike Sultan Ibrahim I | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Mehmed III | ||||

| Mother | Handan Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

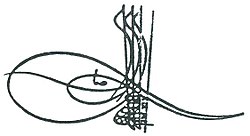

| Tughra |  | ||||

Ahmed I (Ottoman Turkish: احمد اول Aḥmed-i evvel; Turkish: I. Ahmed; 18 April 1590 – 22 November 1617) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1603 to 1617. Ahmed's reign is noteworthy for marking the first breach in the Ottoman tradition of royal fratricide; henceforth, Ottoman rulers would no longer systematically execute their brothers upon accession to the throne.[3] He is also well known for his construction of the Blue Mosque, one of the most famous mosques in Turkey.[4]

Early life

[edit]Ahmed was born at the Manisa Palace, Manisa, probably on 18 April 1590,[5][6] when his father Şehzade Mehmed was still a prince and the governor of the Sanjak of Manisa. His mother was Handan Sultan. After his grandfather Murad III's death in 1595, his father came to Constantinople and ascended the throne as Sultan Mehmed III. Mehmed ordered the execution of his nineteen half brothers. Ahmed's elder brother Şehzade Mahmud was also executed by his father Mehmed on 7 June 1603, just before Mehmed's own death on 22 December 1603. Mahmud was buried along with his mother (Halime Sultan, dead after 1623) in a separate mausoleum built by Ahmed in Şehzade Mosque, Constantinople.

Reign

[edit]Ahmed ascended the throne after his father's death in 1603, at the age of thirteen, when his powerful grandmother Safiye Sultan was still alive. With his accession to the throne, the power struggle in the harem flared up; between his mother Handan Sultan and his grandmother Safiye Sultan, who in the previous reign had absolute power within the walls (behind the throne), in the end, with the support of Ahmed, the fight ended in favor of his mother. Ahmed broke with the traditional fratricide following previous enthronements and did not order the execution of his three years old half-brother Mustafa, the second son of Halime Sultan. Instead, Mustafa was sent to live at the old palace at Bayezit along with his mother and their grandmother, Safiye Sultan. This was most likely due to Ahmed's young age - he had not yet demonstrated his ability to sire children, and Mustafa was then the only other candidate for the Ottoman throne. His brother's execution would have endangered the dynasty, and thus he was spared.[3]

His mother tried to interfere in his affairs and influence his decision, especially she wanted to control his communication and movements. In the earlier part of his reign, Ahmed I showed decision and vigor, which were belied by his subsequent conduct.[citation needed] The wars in Hungary and Persia, which attended his accession, terminated unfavourably for the empire. Its prestige was further tarnished in the Treaty of Zsitvatorok, signed in 1606, whereby the annual tribute paid by Austria was abolished. Following the crushing defeat in the Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–1612) against the neighbouring rivals Safavid Empire, led by Shah Abbas the Great, Georgia, Azerbaijan and other vast territories in the Caucasus were ceded back to Persia per the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha in 1612, territories that had been temporarily conquered in the Ottoman–Safavid War (1578–90). The new borders were drawn per the same line as confirmed in the Peace of Amasya of 1555.[7]

Relations with Morocco

[edit]During his reign the ruler of Morocco was Mulay Zidan whose father and predecessor Ahmad al-Mansur had paid a tribute of vassalage as a vassal of the Ottomans until his death.[8][9][10] The Saadi civil wars had interrupted this tribute of vassalage, but Mulay Zidan proposed to submit to it in order to protect himself from Algiers, and so he resumed paying the tribute to the Ottomans.[8]

Ottoman-Safavid War: 1604–06

[edit]The Ottoman–Safavid War had begun shortly before the death of Ahmed's father Mehmed III. Upon ascending the throne, Ahmed I appointed Cigalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha as the commander of the eastern army. The army marched from Constantinople on 15 June 1604, which was too late, and by the time it had arrived on the eastern front on 8 November 1604, the Safavid army had captured Yerevan and entered the Kars Eyalet, and could only be stopped in Akhaltsikhe. Despite the conditions being favourable, Sinan Pasha decided to stay for the winter in Van, but then marched to Erzurum to stop an incoming Safavid attack. This caused unrest within the army and the year was practically wasted for the Ottomans.[11]

In 1605, Sinan Pasha marched to take Tabriz, but the army was undermined by Köse Sefer Pasha, the Beylerbey of Erzurum, marching independently from Sinan Pasha and consequently being taken prisoner by the Safavids. The Ottoman army was routed at Urmia and had to flee firstly to Van and then to Diyarbekir. Here, Sinan Pasha sparked a rebellion by executing the Beylerbey of Aleppo, Canbulatoğlu Hüseyin Pasha, who had come to provide help, upon the pretext that he had arrived too late. He soon died himself and the Safavid army was able to capture Ganja, Shirvan and Shamakhi in Azerbaijan.[11]

War with the Habsburgs: 1604–06

[edit]The Long Turkish War between the Ottomans and the Habsburg monarchy had been going on for over a decade by the time Ahmed ascended the throne. Grand Vizier Malkoç Ali Pasha marched to the western front from Constantinople on 3 June 1604 and arrived in Belgrade, but died there, so Sokolluzade Lala Mehmed Pasha was appointed as the Grand Vizier and the commander of the western army. Under Mehmed Pasha, the western army recaptured Pest and Vác, but failed to capture Esztergom as the siege was lifted due to unfavourable weather and the objections of the soldiers. Meanwhile, the Prince of Transylvania, Stephen Bocskay, who struggled for the region's independence and had formerly supported the Habsburgs, sent a messenger to the Porte asking for help. Upon the promise of help, his forces also joined the Ottoman forces in Belgrade. With this help, the Ottoman army besieged Esztergom and captured it on 4 November 1605. Bocskai, with Ottoman help, captured Nové Zámky (Uyvar) and forces under Tiryaki Hasan Pasha took Veszprém and Palota. Sarhoş İbrahim Pasha, the Beylerbey of Nagykanizsa (Kanije), attacked the Austrian region of Istria.[11]

However, with Jelali revolts in Anatolia more dangerous than ever and a defeat in the eastern front, Mehmed Pasha was called to Constantinople. Mehmed Pasha suddenly died there, whilst preparing to leave for the east. Kuyucu Murad Pasha then negotiated the Peace of Zsitvatorok, which abolished the tribute of 30,000 ducats paid by Austria and addressed the Habsburg emperor as the equal of the Ottoman sultan. The Jelali revolts were a strong factor in the Ottomans' acceptance of the terms. This signaled the end of Ottoman growth in Europe.[11]

Jelali revolts

[edit]Resentment over the war with the Habsburgs and heavy taxation, along with the weakness of the Ottoman military response, combined to make the reign of Ahmed I the zenith of the Jelali revolts. Tavil Ahmed launched a revolt soon after the coronation of Ahmed I and defeated Nasuh Pasha and the Beylerbey of Anatolia, Kecdehan Ali Pasha. In 1605, Tavil Ahmed was offered the position of the Beylerbey of Shahrizor to stop his rebellion, but soon afterwards he went on to capture Harput. His son, Mehmed, obtained the governorship of Baghdad with a fake firman and defeated the forces of Nasuh Pasha sent to defeat him.[11]

Meanwhile, Canbulatoğlu Ali Pasha united his forces with the Druze Sheikh Ma'noğlu Fahreddin to defeat the Amir of Tripoli Seyfoğlu Yusuf. He went on to take control of the Adana area, forming an army and issuing coins. His forces routed the army of the newly appointed Beylerbey of Aleppo, Hüseyin Pasha. Grand Vizier Boşnak Dervish Mehmed Pasha was executed for the weakness he showed against the Jelalis. He was replaced by Kuyucu Murad Pasha, who marched to Syria with his forces to defeat the 30,000-strong rebel army with great difficulty, albeit with a decisive result, on 24 October 1607. Meanwhile, he pretended to forgive the rebels in Anatolia and appointed the rebel Kalenderoğlu, who was active in Manisa and Bursa, as the sanjakbey of Ankara. Baghdad was recaptured in 1607 as well. Canbulatoğlu Ali Pasha fled to Constantinople and asked for forgiveness from Ahmed I, who appointed him to Timișoara and later Belgrade, but then executed him due to his misrule there. Meanwhile, Kalenderoğlu was not allowed in the city by the people of Ankara and rebelled again, only to be crushed by Murad Pasha's forces. Kalenderoğlu ended up fleeing to Persia. Murad Pasha then suppressed some smaller revolts in Central Anatolia and suppressed other Jelali chiefs by inviting them to join the army.[11]

Due to the widespread violence of the Jelali revolts, a great number of people had fled their villages and a lot of villages were destroyed. Some military chiefs had claimed these abandoned villages as their property. This deprived the Porte of tax income and on 30 September 1609, Ahmed I issued a letter guaranteeing the rights of the villagers. He then worked on the resettlement of abandoned villages.[11]

Ottoman-Safavid War: Peace and continuation

[edit]

The new Grand Vizier, Nasuh Pasha, did not want to fight with the Safavids. The Safavid Shah also sent a letter saying that he was willing to sign a peace treaty, with which he would have to send 200 loads of silk every year to Constantinople. On 20 November 1612, the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha was signed, which ceded all the lands the Ottoman Empire had gained in the war of 1578–90 back to Persia and reinstated the 1555 boundaries.[11]

However, the peace ended in 1615 when the Shah did not send the 200 loads of silk. On 22 May 1615, Grand Vizier Öküz Mehmed Pasha was assigned to organize an attack on Persia. Mehmed Pasha delayed the attack till the next year, until when the Safavids made their preparations and attacked Ganja. In April 1616, Mehmed Pasha left Aleppo with a large army and marched to Yerevan, where he failed to take the city and withdrew to Erzurum. He was removed from his post and replaced by Damat Halil Pasha. Halil Pasha went for the winter to Diyarbekir, while the Khan of Crimea, Canibek Giray, attacked the areas of Ganja, Nakhichevan and Julfa.[11]

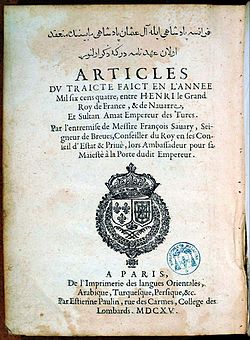

Capitulations and trade treaties

[edit]Ahmed I renewed trade treaties with England, France and Venice. In July 1612, the first ever trade treaty with the Dutch Republic was signed. He expanded the capitulations given to France, specifying that merchants from Spain, Ragusa, Genoa, Ancona and Florence could trade under the French flag.[11]

Architect and service to Islam

[edit]

Sultan Ahmed constructed the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, the magnum opus of the Ottoman architecture,[according to whom?] across from the Hagia Sophia. The sultan attended the breaking of the ground with a golden pickaxe to begin the construction of the mosque complex. An incident nearly broke out after the sultan discovered that the Blue Mosque contained the same number of minarets as the grand mosque of Mecca. Ahmed became furious at this fault and became remorseful until the Shaykh-ul-Islam recommended that he should erect another minaret at the grand mosque of Mecca and the matter was solved.

Ahmed became delightedly involved in the eleventh comprehensive renovations of the Kaaba, which had just been damaged by flooding. He sent craftsmen from Constantinople, and the golden rain gutter that kept rain from collecting on the roof of the Ka’ba was successfully renewed. It was again during the era of Sultan Ahmed that an iron web was placed inside the Zamzam Well in Mecca. The placement of this web about three feet below the water level was a response to lunatics who jumped into the well, imagining a promise of a heroic death.

In Medina, the city of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, a new pulpit made of white marble and shipped from Istanbul arrived in the mosque of Muhammad and substituted the old, worn-out pulpit. It is also known that Sultan Ahmed erected two more mosques in Uskudar on the Asian side of Istanbul; however, neither of them has survived.

The sultan had a crest carved with the footprint of Muhammad that he would wear on Fridays and festive days and illustrated one of the most significant examples of affection to Muhammad in Ottoman history. Engraved inside the crest was a poem he composed:

“If only could I bear over my head like my turban forever thee, If only I could carry it all the time with me, on my head like a crown, the Footprint of the Prophet Muhammad, which has a beautiful complexion, Ahmed, go on, rub your face on the feet of that rose.“

Character

[edit]Sultan Ahmed was known for his skills in fencing, poetry, horseback riding, and fluency in several languages.

Ahmed was a poet who wrote a number of political and lyrical works under the name Bahti. Ahmed patronized scholars, calligraphers, and pious men. Hence, he commissioned a book entitled The Quintessence of Histories to be worked upon by calligraphers. He also attempted to enforce conformance to Islamic laws and traditions, restoring the old regulations that prohibited alcohol, and he attempted to enforce attendance at Friday prayers and paying alms to the poor in the proper way.

Death

[edit]

Ahmed I died of typhus and gastric bleeding on 22 November 1617 at the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul. He was buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque. He was succeeded by his younger half-brother Şehzade Mustafa as Sultan Mustafa I. Later three of Ahmed's sons ascended to the throne: Osman II (r. 1618–22), Murad IV (r. 1623–40) and Ibrahim (r. 1640–48).

Family

[edit]Consorts

[edit]Ahmed had two known consorts, besides many unknown concubines[13], mothers of the other Şehzades and Sultanas.[14][15]

The known consorts are:

- Hatice Mahfiruz Hatun (c. 1590 - ?) first consort and mother to his firstborn son Osman II and most possibly other children including three other sons according to various historians including Öztuna.

- Kösem Sultan (c. 1589 - 2 September 1651). She was his favourite consort, Haseki Sultan, and the mother of many of his children, among them the future Murad IV and Ibrahim I.[16]

Sons

[edit]Ahmed I had at least thirteen sons:

- Osman II (3 November 1604, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace – murdered by janissaries, 20 May 1622, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque) - with Mahfiruz Hatun.[17][18] 16th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire;

- Şehzade Mehmed (11 March 1605, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace – executed by orders of Osman II, 12 January 1621, Istanbul, Topkapı Palace, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque) - with Kösem Sultan ;[19][20]

- Şehzade Orhan (1609, Constantinople – 1612, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque.[21]

- Şehzade Cihangir (1609, Constantinople – 1609, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque).[21]

- Şehzâde Fülane (1610/1611, Constantinople -1612, Constantinople) : He died a year after his birth according to the 1612 report of Venetian Bailo Contarini.[22]

- Şehzade Selim (27 June 1611, Constantinople – 27 July 1611, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque).

- Murad IV (27 July 1612, Constantinople – 8 February 1640, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque) - with Kösem Sultan.[17][23][24][25] 17th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire;

- Şehzade Bayezid (December 1612, Constantinople – murdered by Murad IV, 27 July 1635, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque)-With Mahfiruz Hatun;[17][18]

- Şehzade Hüseyin (November 1613,[26] Constantinople – 1617, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, buried in Mehmed III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) with Mahfiruz Hatun;[17][18][27][28]

- Şehzade Hasan (1614/15,[29] Constantinople – 1615, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque)[21]

- Şehzade Süleyman (1615/16,[30] Constantinople – executed by orders Murad IV, 27 July 1635, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque) - with Mahfiruz Hatun.[17][18][24] Some historians have confused Süleyman with Selim (who had died in 1611 barely a few weeks after his birth according to the Venetian bailo, Contarini's report of 1612) and also with Hüseiyn, but this is a false claim as only Murad, Bayezid, Süleyman, Kasim and Ibrahim were alive during 1622 according to Harem registers and those that were executed by Murad IV were his half-brothers Bayezid and Süleyman on July 27, 1635 and then (most probably Murad's full-brother) Şehzâde Kasim on 17 February 1638.[31][32]

- Şehzade Kasım (1615/16,[33] Constantinople – executed by order of Murad IV, 17 February 1638, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Kösem Sultan;[17][23][24][25]

- Ibrahim I (13 October 1617,[34] Constantinople – 18 August 1648, Constantinople, Topkapı Palace, murdered by janissaries and buried in Ibrahim I Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Kösem Sultan.[17][23][24][25] 18th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.

Daughters

[edit]Ahmed I had at least eleven daughters:

- Fülane Sultan (Early 1605, Constantinople-?) - She was born between the births of her half-brothers Osman and Mehmed. According to Venetian Bailo, Ottovaino Bon's report, her mother was another concubine whose name is not known- a woman other than Mahfiruz and Kösem.[35] She was the oldest daughter of Ahmed I and she was maybe married around 1610.

- Ayşe Sultan (1606,[36] Constantinople – 1657, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque) - with Kösem Sultan,[24]

- Gevherhan Sultan (Late 1608, Constantinople – c. 1660, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque). She was named in honour of Ahmed's great aunt, Gevherhan Sultan who had gifted Ahmed's mother, Handan Sultan to his father, Mehmed III. Earlier she was presumed to have been Kösem's daughter[37][38], however this is an inauthentic claim as Hanzade was determinably one of Kosem's three daughters instead[39] and Gevherhan is now established Osman's full-sister and her marriage in 1612 to Öküz Mehmed Pasha worked as a political leverage for Osman, as the Pasha became Grand Vizier following the execution of Kösem's son-in-law, Nasuh Pasha in 1614 on the orders of Ahmed I.[40]

- Fatma Sultan (Late 1608,[41], Constantinople – 1667, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque) - She was born of Kösem Sultan after the Venetian ambassador, Ottaviano Bon's report of June, 1609 detailing only 2 daughters from 2 different mothers- as the ambassador, Ottaviano read the report in June 1609, the information it reproduces may have been somewhat dated as he had left Istanbul earlier.[42]and her mother was Kösem Sultan;[24][39]

- Hatice Sultan (post 1608, Constantinople – 1610, Constantinople, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque)-[21]

- Hanzade Sultan (1610/11, Constantinople – 21 September 1650, Constantinople, buried in Ibrahim I Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - She is generally considered the youngest of the three daughters of Ahmed I with Kösem Sultan and was definitely born after 1608 as the Venetian Bailo Ottovaino Bon's report was delivered June 1609 mentioned only 2 sons and 2 daughters of Ahmed I by three different women, i.e. only the two oldest surviving daughters of Ahmed I, Gevherhan with an unknown concubine and Ayşe with Kösem are mentioned. With her second full older sister, Fatma's birth estimated to have been around late 1608 or early 1609, she must've been born circa 1610 or early 1611 at the latest definitely before her younger full brother, Murad IV who was born on July 27, 1612.[39][43]

- Esma Sultan (Constantinople, 1612 – Constantinople, 1612, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque)[21]

- Zahide Sultan (Constantinople, 1613 – Constantinople, 1620, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque)[21]

- Burnaz Atike Sultan (c. 1614/1616?, Constantinople – 1674, Constantinople, buried in Ibrahim I Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque). [44] She trained the future Valide Sultan, Turhan before presenting her to her half-brother, Ibrahim I- Turhan later rivalled and prevailed against Kösem Sultan.[45]

- Zeynep Sultan (Constantinople, 1617 – Constantinople, 1619, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque)[21]

- Ümmühan Sultan (ante 1616- after 1688) - She married Shehit Ali Pasha.[46]

- Abide Sultan (Constantinople, 1618 – Constantinople, 1648, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Sultan Ahmed Mosque). Called also Übeyde Sultan, married in 1642 to Koca Musa Pasha (died in 1647)[21]

Legacy

[edit]Today, Ahmed I is remembered mainly for the construction of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque (also known as the Blue Mosque), one of the masterpieces of Islamic architecture. The area in Fatih around the Mosque is today called Sultanahmet. He died at Topkapı Palace in Constantinople and is buried in a mausoleum right outside the walls of the famous mosque.

In popular culture

[edit]In the 2015 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl: Kösem, Ahmed I is portrayed by Turkish actor Ekin Koç.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kumrular, Özlem (2015). Sułtanka Kösem. Władza i intrygi w haremie.[Kösem Sultan. İktidar, Hırs, Entrika] (in Polish). Laurum. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-83-8087-451-0.

- ^ Garo Kürkman, (1996), Ottoman Silver Marks, p. 31

- ^ a b Peirce, Leslie (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 99. ISBN 0-19-508677-5.

- ^ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923. Basic Books (U.S. edition) (published April 24, 2007). ISBN 978-0465023974.

- ^ Börekçi, Günhan. İnkırâzın Eşiğinde Bir Hanedan: III. Mehmed, I. Ahmed, I. Mustafa ve 17. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Siyasî Krizi - A Dynasty at the Threshold of Extinction: Mehmed III, Ahmed I, Mustafa I and the 17th-Century Ottoman Political Crisis. pp. 81 n. 75.

- ^ Börekçi, Günhan (2010). Factions and Favorites at the Courts of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-17) and His Immediate Predecessors. pp. 85 n. 17.

- ^ Ga ́bor A ́goston,Bruce Alan Masters Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire pp 23 Infobase Publishing, 1 jan. 2009 ISBN 1438110251

- ^ a b Les Sources inédites de l'histoire du Maroc de 1530 à 1845. E. Leroux.

- ^ Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, Volume 17.

- ^ Histoire du Maroc. Coissac de Chavrebière. Payot.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Ahmed I" (PDF). İslam Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 1. Türk Diyanet Vakfı. 1989. pp. 30–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (January 1989). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: Fascicules 111-112 : Masrah Mawlid by Clifford Edmund Bosworth p.799. BRILL. ISBN 9004092390. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ Venetian ambassador, Simone Contarini (May 1612): “Ha il re due figliuoli, l’uno di sette, l’altro di sei. […] Tre figliuole femmine si trova avere anco Sua Maestà alla quale nascon pure de’ figliuoli assai spesso, e per l’abbondanza delle donne, e per la gioventù, e prosperità che tiene.”

- ^ Sakaoğlu, Necdet [in Turkish] (2008). Bu mülkün kadın sultanları: Vâlide sultanlar, hâtunlar, hasekiler, kadınefendiler, sultanefendiler. Oğlak Publications. p. 238. ISBN 978-9-753-29623-6.

- ^ Peirce, Leslie (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 250-260 and others. ISBN 0-19-508677-5.

- ^ Kumrular, Özlem (2015). Sułtanka Kösem. Władza i intrygi w haremie [Kösem Sultan. İktidar, Hırs, Entrika] (in Polish). Laurum. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-83-8087-451-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Şefika Şule Erçetin (November 28, 2016). Women Leaders in Chaotic Environments:Examinations of Leadership Using Complexity Theory. Springer. p. 77. ISBN 978-3-319-44758-2.

- ^ a b c d Uluçay, Mustafa Çağatay (2011). Padışahların Kadınları ve Kızları. Ötüken, Ankara. p. 78. ISBN 978-9-754-37840-5.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2007). "The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Political Career". Turcica. 39–40. Éditions Klincksieck: 350–351.

- ^ Börekçi, Günhan (2010). Factions And Favorites At The Courts Of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-17) And His Immediate Predecessors (Thesis). Ohio State University. pp. 117, 142.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yılmaz Öztuna - Sultan Genç Osman ve Sultan IV. Murad

- ^ Tezcan, Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career; pp 348; "...before the birth of Murad, that besides the two princes alive, Ahmed had two other sons; one of them died soon after his birth [Selim], and the other a year after his birth; see Nicolo BAROZZI and Guglielmo BERCHET, eds., Le relazioni degli stati europei lette al senato dagli ambasciatori veneziani nel secolo decimosettimo: Turchia, 2 vols., Venice, 1871-72, vol. 1, p. 125-254, at p. 133 [reprinted in Luigi FIRPO, ed., Relazioni di ambasciatori veneti al senato, tratte dalle migliori edizioni disponibili e ordinate cronologicamente, vol. 13: Constantinopoli (1590-1793), Torino, Bottega d’Erasmo, 1984, p. 473-602, at p. 481].

- ^ a b c Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire: From 1591 to 1659 ..., Volume 1. Oriental Translation Fund, & sold by J. Murray. pp. 452–3.

- ^ a b c d e f Singh, Nagendra Kr (2000). International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties (reproduction of the article by M. Cavid Baysun "Kösem Walide or Kösem Sultan" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam vol V). Anmol Publications PVT. pp. 423–424. ISBN 81-261-0403-1.

- ^ a b c Peirce, Leslie P. (1993), The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, Oxford University Press, p. 232, ISBN 0195086775

- ^ Tezcan, Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career; pp 354; fn 40: SAFI, Zübdetü’t-Tevârîh, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 300

- ^ Gabriele Mandel (1992). Storia dell'harem (in Italian). p. 150.

Ahmed I ebbe solo tre donne: Hadice Mah-firuz, da cui ebbe quattro figli (Osman, Bayezid, Süleyman e Hüseiyn)...

- ^ Güler Eren, Kemal Çiçek, Cem Oğuz (1999). Osmanlı: Kültür ve sanat. 10 (in Turkish).

...başka Mehmed, Süleyman, Bayezid ve Hüseyni adlı 4 şehzade doğmuştur...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tezcan, Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career; pp 354

- ^ Tezcan , Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career pp 354; HASANBEYZADE, Hasan Bey-zâde Târîhi, op. cit., vol. 3, p. 899; KARAÇELEBIZADE, Ravzatü’l-ebrâr, op. cit., p. 534

- ^ Tezcan , Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career pp 355

- ^ Gülru Neci̇poğlu, Julia Bailey (2008). Frontiers of Islamic Art and Architecture: Essays in Celebration of Oleg Grabar's Eightieth Birthday ; the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture Thirtieth Anniversary Special Volume. BRILL. p. 324. ISBN 978-9-004-17327-9.

- ^ Tezcan , Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career pp 354; HASANBEYZADE, Hasan Bey-zâde Târîhi, op. cit., vol. 3, p. 899; KARAÇELEBIZADE, Ravzatü’l-ebrâr, op. cit., p. 534

- ^ Tezcan , Baki: The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career pp 354; fn 43: Mehmed ŞEYHI, Vakâyi'ü’l-fudalâ, 2 vols., Beyazıt Kütüphanesi, MS Veliyüddin Efendi 2361-2362; facs. ed., Abdülkadir ÖZCAN, Şakaik-ı Nu'maniye ve Zeyilleri, 5 vols., Istanbul, Çagrı, 1989, vols. 3-4, vol. 3, p. 150, gives an exact date as 12 Şevvâl 1026 / 13 October 1617

- ^ Tezcan, Baki: THE DEBUT OF KÖSEM SULTAN’S POLITICAL CAREER; “Non ha la Maestà Sua sposata alcuna schiava fin hora, et si ritrova haver con tredonne quattro figli, due maschi et due femine. Il maggiore, destinato alla successione, haverà cinque anni forniti;” the relation of Ottaviano Bon, read to the Venetian Senate on June 9, 1609, in Maria Pia PEDANI-FABRIS, ed., Relazioni di ambasciatori veneti al senato, vol. 14: Constantinopoli, Relazioni inedite (1512-1789) (Padova: Bottega d’Erasmo,1996), p. 475-523, at p. 514.

- ^ Ayşe and her sister, Fatma were born- one around 1606 immediate to their elder brother, Mehmed and one by late 1608 or early 1609, but historians are uncertain about assigning dates. Ayşe is generally considered older than Fatma according to the Harem records which list residents in accordance with seniority.

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kr (2000). International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties (reproduction of the article by M. Cavid Baysun "Kösem Walide or Kösem Sultan" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam vol V). Anmol Publications PVT. pp. 423–424. ISBN 81-261-0403-1.

Through her beauty and intelligence, Kösem Walide was especially attractive to Ahmed I, and drew ahead of more senior wives in the palace. She bore the sultan four sons – Murad, Süleyman, Ibrahim and Kasim – and three daughters – 'Ayşe, Fatma and Djawharkhan. These daughters she subsequently used to consolidate her political influence by strategic marriages to different viziers.

- ^ Peirce, Leslie P. (1993), The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, Oxford University Press, p. 365, ISBN 0195086775

- ^ a b c Peirce, Leslie P. (1993), The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, Oxford University Press, p. 365, ISBN 0195086775

- ^ Tezcan, Baki; The Debut of Kösem Sultan's Career; pp 356

- ^ “Non ha la Maestà Sua sposata alcuna schiava fin hora, et si ritrova haver con tredonne quattro figli, due maschi et due femine. Il maggiore, destinato alla successione,haverà cinque anni forniti;” the relation of Ottaviano Bon, read to the Venetian Senate on June 9, 1609, in Maria Pia PEDANI-FABRIS, ed., Relazioni di ambasciatori veneti al senato, vol. 14: Constantinopoli, Relazioni inedite (1512-1789) (Padova: Bottega d’Erasmo, 1996), p. 475-523, at p. 514.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki: THE DEBUT OF KÖSEM SULTAN’S POLITICAL CAREER

- ^ “Non ha la Maestà Sua sposata alcuna schiava fin hora, et si ritrova haver con tredonne quattro figli, due maschi et due femine. Il maggiore, destinato alla successione,haverà cinque anni forniti;” the relation of Ottaviano Bon, read to the Venetian Senate on June 9, 1609, in Maria Pia PEDANI-FABRIS, ed., Relazioni di ambasciatori veneti al senato, vol. 14: Constantinopoli, Relazioni inedite (1512-1789) (Padova: Bottega d’Erasmo, 1996), p. 475-523, at p. 514.

- ^ Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2008). Bu mülkün kadın sultanları: Vâlide sultanlar, hâtunlar, hasekiler, kadınefendiler, sultanefendiler. Oğlak Yayıncılık. p. 235.

- ^ Dumas, Juliette; Les perles de nacre du sultanat; Pg 345: "...la reine mère Turhan Hadice Sultane avait été formée par Atike Sultane avant d’être offerte au sultan. La collusion entre la maison impériale et les maisons princières se repère jusque dans les échanges de femmes esclaves..."

- ^ Ghobrial, John-Paul A. (2013). The Whispers of Cities: Information Flows in Istanbul, London, and Paris in the Age of William Trumbull. OUP Oxford. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-19-967241-7.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Ahmed I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ahmed I at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Works by or about Ahmed I at Wikisource

Works by or about Ahmed I at Wikisource