Strasbourg massacre

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

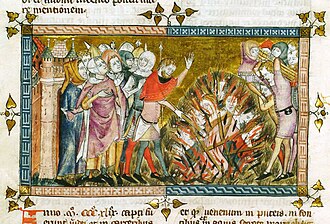

The Strasbourg massacre occurred on 14 February 1349, when the entire Jewish community of several thousand Jews were publicly burnt to death as part of the Black Death persecutions.[1]

Starting in the spring of 1348, pogroms against Jews had occurred in European cities, starting in Toulon. By November of that year they spread via Savoy to German-speaking territories. In January 1349, burnings of Jews took place in Basel and Freiburg, and on 14 February the Jewish community in Strasbourg was destroyed.

This event was heavily linked to a revolt by the guilds five days previously, the consequences of which were the displacement of the master tradesmen, a reduction of the power of the patrician bourgeoisie, who had until then been ruling almost exclusively, and an increase in the power of the groups that were involved in the revolt. The aristocratic families of Zorn and Müllenheim, which had been displaced from the council and their offices in 1332, recovered most of their power. The guilds, which until then had no means of political participation, could occupy the most important position in the city, that of the Ammanmeister. The revolt had occurred because a large part of the population on the one hand believed the power of the master tradesmen was too great, particularly that of the then-Ammanmeister Peter Swarber, and on the other hand, there was a desire to put an end to the policy of protecting Jews under Peter Swarber.

Causes

[edit]Antisemitism in the population

[edit]

Jews in Strasbourg were forbidden by local law, and often canon law, to own land or to be farmers. As one of the few roles available to them was money-lending, Jews took an important position in the city's economy. However, this led to conflict. Formally, the Jews still belonged to the King's chamber, but he had long since ceded these rights to the city (the confirmation of the relevant rights of the city by Charles IV occurred in 1347). Strasbourg therefore took in the most part of the Jews' taxes, but in exchange had to take over their protection (the exact amount of the taxes was determined by written agreements). Pressure to meet tax obligations affected the Jews' business practices and fueled anti-Semitism among the population and particularly among the Jews' debtors.

With the threat of Black Death, there were also accusations of well poisoning, and calls for the burning of Jews.

The government's policy of protecting Jews

[edit]The council and the master tradesmen attempted to calm the people and prevent a pogrom. The Catholic clergy had been advised by two papal bulls of Pope Clement VI the previous year (July and September 1348) to preach against anyone accusing the Jews of poisoning wells as "seduced by that liar, the Devil."

Tactical measures

[edit]At first the council tried to rebut the claims of well poisoning by initiating court proceedings against a number of Jews and torturing them. As expected, they did not confess to the crimes. Despite this, they were still killed on the breaking wheel. Furthermore, the Jewish quarter was sealed off and guarded by armed persons, in order to protect the Jews from the population and possible over-reactions. There were concerns that a pogrom could escalate and turn into an uncontrollable revolt of the people, as evidenced by a letter from the city council of Cologne on 12 January 1349 to the leaders of Strasbourg,[2] which warned that such riots by the common people had led to much evil and devastation in other towns.

Rebellion of the artisans

[edit]On Monday 9 February, the artisans gathered in front of the cathedral and, in front of the crowd, informed the masters that they would not allow them to remain in office anymore, as they had too much power. This action appears to have been organised beforehand among the guilds. The masters attempted to persuade the artisans to break up the assembled crowd—without success—but made no moves to comply with the rebels' demands. After an exhaustive debate which involved not only the guilds' representatives but also prominent knights and citizens, it became clear to the masters that they lacked support, and so they gave up their posts. One craftsman became Ammanmeister, namely "Betscholt der metziger." Swarber was also stripped of his property during this day.[2]

Organisers of the coup

[edit]The noble families of Zorn and Müllenheim, who had been forced from power at that time, cooperated with the guilds in an attempt to regain their old position of power. The nobles cooperated not only with the guilds, but also with the Bishop of Strasbourg. On that occasion, the Strasbourg bishop, representatives of the cities of Strasbourg, Freiburg and Basel, and Alsatian local rulers met in Benfeld, in order to plan their actions towards the Jews. Peter Swarber was aware of this agreement by the bishop and Alsatian nobles, which is why he warned: if the bishop and the nobles were successful against him in the "Jewish issue", they would not rest until they were also successful in other cases. But he was not able to dissuade from the anti-Jewish stance.

Result of the coup

[edit]Through the coup, the old noble families regained a great deal of their former power, the guilds regained their political participation, and many expected an anti-Semitic policy from the new political leadership (whereas between 1332 and 1349 not one nobleman had held the office of a master, now two of four town masters were nobles). The demand to reduce the power of the masters was also granted. The old masters were punished (the town masters were banned from election to the council for 10 years, the hated Peter Swarber was banished, his assets confiscated), the council was dissolved and reconstituted in the next three days, and the pogrom began a day later.

The pogrom

[edit]The two deposed officials were left with the task of leading the Jews to the place of their execution, the Jewish cemetery,[2] pretending to lead them out of Strasbourg. At this place, a wooden house had been built in which the Jews were burnt alive. Those Jews who were willing to get baptized as well as children and any women considered attractive were spared from the burning alive. The massacre is said to have lasted six days.

Result

[edit]After getting rid of the Jews, the murderers distributed the Jews' properties among themselves. Many of those who promoted the overthrow were in debt of the Jews, and were able to eliminate their debts in the aftermath. Apart from Strasbourg nobles and citizens, Bishop Berthold von Buchegg was also indebted to the Jews, as were several of the landed gentry, and even some sovereign princes such as the Margrave of Baden and the Count of Württemberg. The cash of the Jews was divided among the artisans by decision of the council, maybe as a sort of "reward" for their support in overthrowing the master tradesmen.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wallace, Albin (4 August 2023). The Effects of The Black Death in England: Magna Mortalitas. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-5275-2834-5. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ a b c Steven, Rowan. "The Grand Peur of 1348-49: The Shock Wave of the Black Death in the German Southwest". ScholarsArchive. Brigham Young University. Retrieved 13 June 2025.