Skhul and Qafzeh hominins

32°41′18″N 35°19′06″E / 32.68833°N 35.31833°E

The Skhul and Qafzeh hominins or Qafzeh–Skhul early modern humans[1] are hominin fossils discovered in Es-Skhul and Qafzeh caves in Israel. They are today classified as Homo sapiens, among the earliest of their species in Eurasia. Skhul Cave is on the slopes of Mount Carmel; Qafzeh Cave is a rockshelter near Nazareth in Lower Galilee.

The remains found at Es Skhul, together with those found at the Nahal Me'arot Nature Reserve and Mugharet el-Zuttiyeh, were classified in 1939 by Arthur Keith and Theodore D. McCown as Palaeoanthropus palestinensis, a descendant of Homo heidelbergensis.[2][3][4]

Research history

[edit]Discovery

[edit]In 1928, Mandatory Palestine planned to mine the cliffs of Nahal Me'arot (a valley in the Carmel mountain range) for construction of a deep-water harbour in the city of Haifa roughly 19 km (12 mi) north. The Department of Antiquities, already suspecting the archaeological value of the many openly-visible caves in the area, sent the assistant director — C. Lambert — on a three-week trial excavation of El Wad in November. Lambert discovered several stone tools, quern-stones, beads, stone constructions, and human fossils, as well as the first published discovery of Near Eastern Stone Age art (an animal-shaped bone sickle). The British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem partnered with the American School of Prehistoric Research (ASPR) to fund seven field seasons from 1929 to 1934 of the region's caves under the direction of British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod.[5]

She invited American archaeologist Theodore D. McCown to excavate Skhul Cave, who joined as a field representative of the ASPR as part of his graduate program with University of California, Berkeley. On 3 May 1931, McCown unearthed a fossil child skeleton (Skhul I); and on 30 April 1932 (with his assistant Hallam L. Movius), he discovered another skeleton (Skhul II), a partial skull and jaw (Skhul III), and a nearly complete skeleton (Skhul IV). On 3 May 1932, McCown and Movius discovered another nearly complete skeleton (Skhul V), and a partial skeleton (Skhul VI). McCown found another partial skull (Skhul VII) and child skeleton (Skhul VIII) on 13 May, a partial skeleton (Skhul IX) on 19 May, and an infant skeleton (Skhul X) while studying the material in 1935.[6]

The full excavation history of the site, archaeological finds, palaeoenvironmental studies, and anatomical description of the fossil material was published in a two-volume monograph in 1937; volume 1 published by Garrod and Welsh palaeontologist Dorothea Bate, and volume 2 by McCown and British anatomist Sir Arthur Keith. The skeletons were removed from stone matrices principally under the direction of McCown at the Royal College of Surgeons of England over the course of three years, aided by his assistants Margot Collett and W. C. Willmott. Keith and McCown were able to study the material at the Buckston Browne Research Farm, and afterwards they repatriated the material back to Mandatory Palestine. The material from Skhul Cave, as well as the nearby Tabun Cave, represented one of the most complete samples of the human fossil record at the time.[7]

In 1951, American anthropologist Francis Clark Howell recognised the similarities between the Skhul remains and human fossils exhumed about 35 km (22 mi) east from Qafzeh Cave by French consulate René Neuville beginning in 1934. The connection was initially unpopular because the Qafzeh material was unpublished and the stratigraphy and age were uncertain. In 1963, the Israeli ambassador to France, Walter Eytan, suggested to French palaeontologist Jean Piveteau to continue excavation of Qafzeh, which recommenced under Piveteau and his student Jean Perrot in July 1965. Their work cemented the connection between Skhul and Qafzeh.[8]

Age and stratigraphy

[edit]In 1937, Garrod and Bate divided the 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) thick reddish-brown breccia of Skhul Cave into three layers: the 60 cm (2 ft) Layer A yielding pottery fragments and Middle to Upper Palaeolithic artefacts; the 2 m (6 ft 7 in) Layer B yielding at least 10 fossil individuals and around 9,800 stone tools; and the 30 cm (1 ft) Layer C yielding some stone tools of the same culture as Layer B.[9] They concluded that Skhul Layers B and C are roughly contemporaneous with the Neanderthal fossils of Tabun Cave Layers B and C, and date to the Riss-Würm interglacial (the Middle Pleistocene) based on the animal remains (biostratigraphy). Layer B of Tabun lacks wild cattle and instead has a preponderance of gazelle, unlike the older Tabun C as well as Skhul B, so Garrod and Bate suggested that Tabun B was deposited in a younger, dryer period than Skhul B (presuming wild cattle require wetter conditions). That is, the Skhul B material which better resembles modern humans was older than the Tabun B material which better resembles Neanderthals.[10]

In 1957, Howell asserted that the Skhul and Tabun material must date to the Early Last Pluvial (the early Last Glacial Period during the Late Pleistocene).[11] In 1961, British archaeologist Eric Sidney Higgs rejected Garrod and Bates' arguments for Skhul B dating to a wetter period older than Tabun B, suggesting Skhul B might actually be from a dry period younger than Tabun B.[12] In general, most workers opted to date the Neanderthals of the region (Tabun, Amud, Kebara) to about 50,000 years ago, and the modern humans of Skhul and Qafzeh to 40,000 years ago.[9]

In 1988, French palaeontologist Hélène Valladas and colleagues dated stone tools from Qafzeh using thermoluminescence dating to about 90,000–100,000 years ago (at the time, nearly as old as some of the oldest modern human fossils from Africa).[13] In 1989, British physical anthropologist Chris Stringer and colleagues used electron spin resonance dating of bovine teeth at Skhul to date the human fossils to roughly 80,000–100,000 years ago. This meant that modern humans quickly dispersed from Africa soon after evolution, but did not penetrate Europe for tens thousands of years. Further, Skhul and Qafzeh were older than Tabun and other Neanderthal sites, implying that modern humans were replaced by Neanderthals.[9]

Classification

[edit]Raciology

[edit]

McCown and Keith noted that the Tabun material more closely resembled Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), while the Skhul material better resembled later Cro-Magnons (modern humans, H. sapiens). Nonetheless, they opted to recognise the Tabun and Skhul populations as belonging to the same (highly variable) species based on cultural and dental similarity, and because they were thought to be contemporaries at the time. They also grouped Keith's 1925 Galilee Man discovered 56 km (35 mi) away into this group (but on the Tabun end of variation). They believed the population was closely related to the last common ancestor of Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons, "in the throes of an evolutionary transition," envisioning a geographic grade ranging from the "evolutionary backwater" of Western Europe with the "Palaeoanthropic" (less evolved) classic Neanderthals, to the "Neanthropic" (more evolved) Near East. That is, from Western Europe to the Near East, human populations became more evolutionarily advanced, with the homeland of the most-evolved Caucasian race lying somewhere farther east in Asia.[14] They concluded that invading Caucasian Near Eastern immigrants racially advanced Europe during the Palaeolithic, similar to how immigrating Near Eastern farmers would later advance Europe to the Neolithic.[15]

In brief, our theory assumes that Europe became the 'Australia' of the ancient world after mid-Pleistocene times and that the people who colonized it and extinguished its Neanderthal inhabitants, as the whites are now ousting the 'blacks' of Australia, were Caucasians evolved in western Asia.

McCown and Keith opted to classify the Tabun and Skhul remains as a new species, "Palaeoanthropus palestinensis". The genus "Palaeoanthropus" was erected in 1909 by Italian palaeontologist Guido Bonarelli to house the far more ancient German Mauer 1 (originally Homo heidelbergensis). They retained "P. heidelbergensis" as the earliest member of this evolutionary lineage. The other species they designated (from west to east) are: "P. neanderthalensis" (specifically the French La Chappelle-aux-Saints 1 and Western German Neanderthal 1), the Central German "P. ehringsdorfiensis", and the Croatian "P. krapinensis",[15] with "P. krapinensis" as the closest relative of "P. palestinensis", serving to, "bridge the gap between the ancient Palestinians and the Neanderthalians of western Europe."[16] They noted that the Middle Pleistocene German Steinheim skull, which they considered to be the earliest known Neanderthal type in Europe, has more in common with the Tabun and Skhul material than with European Neanderthals.[17]

Modern evolutionary synthesis

[edit]In the 1940s, the formulation of modern evolutionary synthesis and the burgeoning field of population genetics shifted the popular interpretations of fossil populations and the definition of "species" in palaeontology. Notably, Jewish-German anatomist Franz Weidenreich and Russian-American geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky argued that only one widespread species of human should be recognised as existing at any one point in time, which can be subdivided into geographic subspecies or races.[18]

In 1944, Dobzhansky stated that it was more probable that the Tabun and Skhul material are the result of interbreeding between archaic and modern humans, which should naturally occur (in this case quite frequently) when "Neanderthaliens" (Tabun) and H. sapiens (Skhul) are in proximity. He further said that the lack of reproductive isolation between Neanderthals and modern humans demonstrated by Tabun and Skhul is proof that they are different races of the same species, exclaiming, "This shows how rash are the assertions of some writers that in fossil forms evidence on presence or absence of reproductive isolation can never be obtained!"[18]

On the basis of the available data there is no reason to suppose that more than a single hominid species has existed on any time level in the Pleistocene. Particularly, the findings of McCown and Keith on Mount Carmel prove that the Neanderthal and modern types were races of the same species rather than distinct species.

— Theodosius Dobzhansky, 1944[18]

Similarly, in 1950, German-American evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, surveying a "bewildering diversity of names", subsumed human fossils into three species of Homo: "H. transvaalensis" (the australopithecines), H. erectus, and H. sapiens — with each species directly evolving into the next with no overlap (chronospecies). He justified sinking Neanderthals into a subspecies of H. sapiens as H. s. neanderthalensis using the Skhul and Tabun material, commenting, "The fact remains that Mt. Carmel man makes the delimitation of modern man from Neanderthal exceedingly difficult, if not impossible."[19]

Subsequently, many authors favoured recognising a Neanderthal phase in human evolution, which would terminate with anatomically modern humans and classic Neanderthals. In 1951, Howell distinguished classic Neanderthals of the Würm glaciation from "early Neanderthals" of the Riss-Würm interglacial, which he placed as the ancestral stock of both classic Neanderthals and modern humans. He included Skhul and Tabun as a Southwest Asian variety of early Neanderthal — a population ancestral to modern humans, as opposed to a hybrid population. He also considered the reach of that specific population represented at Mount Carmel to Galilee Man, the Uzbekistani Teshik-Tash 1, and the (at the time undescribed) material of Qafzeh Cave.[20]

In 1957, Howell redated all of these sites to the Early Last Pluvial, making them contemporaneous with classic Neanderthals. He further argued that there is no evidence that Skhul is contemporaneous with Tabun. He envisioned a lineage descending from the population represented by the Tunisian Tighennif jaw (from the Great Interglacial) going through a "sapiensization" event during the Last Interglacial, which led to Skhul and Qafzeh, and eventually Cro-Magnons. Concurrently, the population represented by the German Swanscombe and Steinheim skulls (also from the Great Interglacial) led to early Neanderthals in the Last Interglacials, which persisted in the Near East (Tabun) as well as Eastern and Central Europe, but underwent "Neanderthalization" in Southern and Western Europe.[11] Howell's association of Qafzeh with Skhul was largely unpopular until Qafzeh was better excavated and studied by Piveteau and Perrot from 1965 to 1979.[8] In general, H. sapiens was commonly divided into "archaic" and "anatomically modern" groups, with the former encompassing European and African Middle Pleistocene fossils and the Late Pleistocene classic Neanderthals; and the latter, groups such as the Skhul and Qafzeh hominins, and Cro-Magnons.[21]

Cladistics

[edit]The expansion of the European and African fossil record through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s conflicted with the one-species model, with workers like British physical anthropologist Chris Stringer arguing to recognize several coexisting Homo species. Once radiometric dating established the chronology of the many fossil-bearing Levantine cave sites, many authors opted to recognize two distinct species occupying the area in the early Late Pleistocene: anatomically modern humans (H. sapiens) and Neanderthals (H. neanderthalensis). While the Skhul and Qafzeh hominins differ in many aspects from later human specimens, they are most closely allied to other anatomically modern humans of North Africa than to the local Neanderthal population.[21]

Skhul and Qazfeh, thus, represented an early dispersal of modern humans out of Africa beginning maybe at the start of the Late Pleistocene roughly 120,000 years ago. Modern humans were later replaced by Neanderthals, until a second modern human dispersal from Africa roughly 70,000 years ago. This dispersal would then go on to colonize the rest of the world. In 2018, modern human fossils from Misliya Cave (also around Mount Carmel) were dated to 177,000 years ago, which could indicate modern human populations fluctuated in and out of the Levant several times (maybe in response to environmental stressors), possibly even before 200,000 years ago.[22]

In 2000, a Neanderthal (C1) from Tabun was estimated to be about 122,000 years old,[23] and in 2005, a set of seven Neanderthal teeth from Tabun were dated to around 90,000 years ago. These dates open the possibility that modern humans from Skhul and Qafzeh and Neanderthals from Tabun inhabited the Levant at the same time.[24]

A 2021 phylogeny of some Middle and Late Pleistocene modern human fossils using tip dating:[25]

Skhul

[edit]The Skhul remains (Skhul 1–9) were discovered between 1929 and 1935 in the Es-Skhul Cave on Mount Carmel. The remains of seven adults and three children were found, some of which (Skhul 1, 4, and 5) are claimed to have been burials.[26] Assemblages of perforated Nassarius shells (a marine genus), which are significantly different from local fauna, have also been recovered from the area, suggesting that these people may have collected and employed the shells as beads,[27] as they are unlikely to have been used as food.[28]

Skhul Layer B has been dated to an average of 81,000–101,000 years ago with the electron spin resonance method, and to an average of 119,000 years ago with the thermoluminescence method.[29][30]

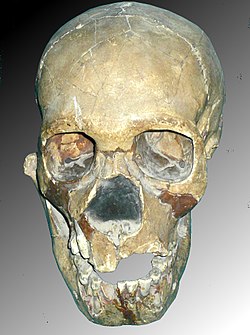

Skhul 5

[edit]Skhul 5 had the mandible of a wild boar on its chest.[26] The skull displays prominent supraorbital ridges and jutting jaw, but the rounded braincase of modern humans. When found, it was assumed to be an advanced Neanderthal, but is today generally assumed to be a modern human, if a very robust one.[31]

Qafzeh

[edit]

Qafzeh cave opens onto a wall of Wadi el Hadj in the flank of Mount Precipice. Excavation of the cave by René Neuville began in 1934 and resulted in the discovery of the remains of 5 individuals in the Mousterian stratigraphic levels, which was then called the Levalloiso-Mousterian[32] (see Levallosian). The lower layers of the cave were later dated to 92,000 years ago,[33] and a series of hearths, several human bodies, flint artifacts (side scrapers, disc cores, and points[34]), animal bones (gazelle, horse, fallow deer, wild ox, and rhinoceros[34]), a collection of sea shells, lumps of red ochre, and an incised cortical flake were found.[33]

The remains of 15 hominids, 8 of them children, were recovered in total from Qafzeh within a Mousterian archaeological context and dated to ca. 95,000 years ago.[35] Remains of Qafzeh 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 and 15 were burials.[26]

The marine shells (Glycymeris bivalves) were brought from Mediterranean Sea shore some 35 km away, and were recovered from layers earlier than most of the bodies save one.[33] The shells were complete, naturally perforated, and several showed traces of having been strung (perhaps as a necklace), and a few had ochre stains on them.[33]

The various layers at Qafzeh were dated to an average of 96,000–115,000 years ago with the electron spin resonance method and 92,000 years ago with the thermoluminescence method.[29]

Qafzeh 9 and 10

[edit]Two skeletons were found in 1969 in the same burial, the skeleton of a late adolescent whose sex is debated (Qafzeh 9),[36] and the skeleton of a young child (Qafzeh 10).[32] Qafzeh 9 has a high forehead, lack of occipital bun, a distinct chin, but a prognathic face.[37] Qafzeh 9 offers the earliest evidence of associated mandibular and dental pathological conditions (i.e. non-ossifying fibroma of the mandible, pre-eruptive intracoronal resorption and osteochondritis dissecans of the temporomandibular joint) among early anatomically modern humans[38]

Qafzeh 11

[edit]

Found in 1971 was the body of an adolescent (aged about 13 years[39]) found in a pit dug in the bedrock. The skeleton was lying on its back, with the legs bent to the side and both hands placed on either side of the neck, and in the hands were the antlers of a large red deer clasped to the chest.[26][32]

Qafzeh 12

[edit]A child of about 3 years old who manifests with skeletal abnormalities that indicate hydrocephalus.[35]

Qafzeh 25

[edit]Qafzeh 25 was discovered in 1979. Due to his overall robustness and tooth wear, the remains are believed to be of a young male.[40] The fossil has undergone heavy taphonomical damages including a complete crushing of the skull and mandible.[41] Its inner ear morphology confirm that it is an anatomically modern human [42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Trinkaus, E. (1993). "Femoral neck-shaft angles of the Qafzeh-Skhul early modern humans, and activity levels among immature near eastern Middle Paleolithic hominids". Journal of Human Evolution. 25 (5). INIST-CNRS: 393–416. doi:10.1006/jhev.1993.1058. ISSN 0047-2484.

- ^ The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial, Paul Pettitt, 2013, p. 59

- ^ Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary, Ryan J. Rabett, 2012, p. 90

- ^ The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: report of the Joint Expedition of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the American School of Prehistoric Research, 1929–1934, p. 18

- ^ Weinstein-Evron, Mina; Kaufmen, Daniel; Rosenburg, Danny; Liberty-Shalev, R. (2013). "The Mount Carmel Caves as a World Heritage Site". Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology: 206–210. ISBN 978-84-695-6782-1.

- ^ Goodrum, Matthew (2022). "Theodore McCown (1908-1969)". Biographical Dictionary of the History of Paleoanthropology.

- ^ McCown & Keith 1937, pp. v–ix.

- ^ a b Vandermeersch, Bernard (2002). "The excavation of Qafzeh". Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (10): 65–70. ISSN 2075-5287.

- ^ a b c Stringer, C. B.; Grün, R.; Schwarcz, H. P.; Goldberg, P. (1989). "ESR dates for the hominid burial site of Es Skhul in Israel". Nature. 338 (6218): 756–758. doi:10.1038/338756a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ McCown & Keith 1937, p. 11.

- ^ a b Howell, F. Clark (1957). "The Evolutionary Significance of Variation and Varieties of "Neanderthal" Man". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 32 (4): 337–343. doi:10.1086/401978. ISSN 0033-5770.

- ^ Higgs, E. S. (1961). "Some Pleistocene Faunas of the Mediterranean Coastal Areas". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 27: 153. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00016017. ISSN 0079-497X.

- ^ Valladas, H.; Reyss, J. L.; Joron, J. L.; Valladas, G.; Bar-Yosef, O.; Vandermeersch, B. (1988). "Thermoluminescence dating of Mousterian Troto-Cro-Magnon' remains from Israel and the origin of modern man". Nature. 331 (6157): 614–616. doi:10.1038/331614a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b McCown & Keith 1937, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c McCown & Keith 1937, p. 18.

- ^ McCown & Keith 1937, pp. 14–15.

- ^ McCown & Keith 1937, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1944). "On species and races of living and fossil man". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2 (3): 251–265. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330020303. ISSN 1096-8644.

- ^ Mayr, E. (1950). "Taxonomic categories in fossil hominids". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 15 (0): 109–118. doi:10.1101/SQB.1950.015.01.013.

- ^ a b Howell, F. Clark (1951). "The place of Neanderthal man in human evolution". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 9 (4): 409–410. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330090402. ISSN 1096-8644.

- ^ a b Stringer, Chris B. (1996). "Current Issues in Modern Human Origins". In Meikle, William Eric; Howell, F. Clark; Jablonski, Nina G (eds.). Contemporary Issues in Human Evolution. California Academy of Sciences. pp. 126–130. ISBN 978-0-940228-45-0.

- ^ Hershkovitz, Israel; Weber, Gerhard W.; Quam, Rolf; Duval, Mathieu; Grün, Rainer; Kinsley, Leslie; Ayalon, Avner; Bar-Matthews, Miryam; Valladas, Helene; Mercier, Norbert; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Martinón-Torres, María; Bermúdez de Castro, José María; Fornai, Cinzia; Martín-Francés, Laura; Sarig, Rachel; May, Hila; Krenn, Viktoria A.; Slon, Viviane; Rodríguez, Laura; García, Rebeca; Lorenzo, Carlos; Carretero, Jose Miguel; Frumkin, Amos; Shahack-Gross, Ruth; Bar-Yosef Mayer, Daniella E.; Cui, Yaming; Wu, Xinzhi; Peled, Natan; Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Weissbrod, Lior; Yeshurun, Reuven; Tsatskin, Alexander; Zaidner, Yossi; Weinstein-Evron, Mina (2018). "The earliest modern humans outside Africa". Science. 359 (6374): 456–459. doi:10.1126/science.aap8369. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Grun R.; Stringer C. B. (2000). "Tabun revisited: revised ESR chronology and new ESR and U-series analyses of dental material from Tabun C1". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (6): 601–612. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0443. PMID 11102271.

- ^ Coppa, Alfredo (2005). "Newly recognized Pleistocene human teeth from Tabun Cave, Israel". Journal of Human Evolution. 49 (3): 301–315. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.04.005. PMID 15964608. Alfredo Coppa, Rainer Grün, Chris Stringer, Stephen Eggins, and Rita Vargiu Journal of Human Evolution Volume 49, Issue 3, September 2005, Pages 301-315

- ^ Ni, Xijun; Ji, Qiang; Wu, Wensheng; Shao, Qingfeng; Ji, Yannan; Zhang, Chi; Liang, Lei; Ge, Junyi; Guo, Zhen; Li, Jinhua; Li, Qiang; Grün, Rainer; Stringer, Chris (2021). "Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100130. Bibcode:2021Innov...200130N. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. ISSN 2666-6758. PMC 8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ a b c d Hovers, Erella; Kuhn, Steven (2007). Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 171–188. ISBN 978-0-387-24661-1. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ Mariah Vanhaeran; Francesco d'Errico; Chris Stringer; Sarah L. James; Jonathan A. Todd; Henk K. Mienis (2006). "Middle Paleolithic Shell Beads in Palestine and Algeria". Science. 312 (5781): (5781): 1785–1788. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1785V. doi:10.1126/science.1128139. PMID 16794076. S2CID 31098527. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer, 2004

- ^ a b Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1998) "The chronology of the Middle Paleolithic of the Levant." In T. Akazawa, K. Aoki, and O. Bar-Yosef, eds. Neandertals and modern humans in Western Asia. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 39–56.

- ^ Valladas, Helene, Norbert Mercier, Jean-Louis Joron, and Jean-Louis Reyss (1998) "Gif Laboratory dates for Middle Paleolithic Levant." In T. Akazawa, K. Aoki, and O. Bar-Yosef, eds. Neandertals and modern humans in Western Asia. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 69–75.

- ^ McHenry, H. "Skhūl". Britannica, academic version. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Bernard Vandermeersch, The excavation of Qafzeh, Bulletin du Centre de recherche français de Jérusalem, retrieved 12 July 2010. http://bcrfj.revues.org/index1192.html

- ^ a b c d Bar-Yosef Mayer, Daniella E.; Vandermeersch, Bernard; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2009). "Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Palestine: indications for modern behavior". Journal of Human Evolution. 56 (3): 307–314. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.005. PMID 19285591.

- ^ a b Jabel Qafzeh http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/archaeology/sites/middle_east/jabel_qafzeh.htm Archived 4 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b Brief communication: An early case of hydrocephalus: The Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh 12 child (Palestine) Anne-Marie Tillier, Baruch Arensburg, Henri Duday, Bernard Vandermeersch (2000) http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/76510952/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0 Archived 5 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ Coutinho-Nogueira, Dany; Coqueugniot, Hélène; Tillier, Anne-marie (10 September 2021). "Qafzeh 9 Early Modern Human from Southwest Asia: age at death and sex estimation re-assessed". HOMO. 72 (4): 293–305. doi:10.1127/homo/2021/1513. PMID 34505621. S2CID 237469414.

- ^ Cartmill, M., Smith, F.H. and Brown, K.B. (2009). The Human Lineage.

- ^ Coutinho Nogueira, D.; Dutour, O.; Coqueugniot, H.; Tillier, A. -m. (1 September 2019). "Qafzeh 9 mandible (ca 90–100 kyrs BP, Israel) revisited: μ-CT and 3D reveal new pathological conditions" (PDF). International Journal of Paleopathology. 26: 104–110. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2019.06.002. PMID 31351220. S2CID 198953011.

- ^ Perikymata number and spacing on early modern human teeth: evidence from Qafzeh cave, Palestine J. M. Monge, A.-m. Tillier & A. E. Mann

- ^ Schuh, Alexandra; Dutailly, Bruno; Coutinho Nogueira, Dany; Santos, Frédéric; Arensburg, Baruch; Vandermeersch, Bernard; Coqueugniot, Hélène; Tillier, Anne-Marie (2017). "La mandibule de l'adulte Qafzeh 25 (Paléolithique moyen), Basse Galilée. Reconstruction virtuelle 3D et analyse morphométrique" (PDF). Paléorient. 43 (1): 49–59. doi:10.3406/paleo.2017.5751. S2CID 164499671.

- ^ Coutinho Nogueira, Dany (2019). Paléoimagerie appliquée aux Homo sapiens de Qafzeh (Paléolithique moyen, Levant sud). Variabilité normale et pathologique. Paris: Thesis of Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, PSL University. p. 201.

- ^ Coutinho-Nogueira, Dany; Coqueugniot, Hélène; Santos, Frédéric; Tillier, Anne-marie (20 August 2021). "The bony labyrinth of Qafzeh 25 Homo sapiens from Israel" (PDF). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 13 (9): 151. Bibcode:2021ArAnS..13..151C. doi:10.1007/s12520-021-01377-2. ISSN 1866-9557. S2CID 237219305.

Bibliography

[edit]- McCown, T. D.; Keith, A. (1937). The stone age of Mount Carmel : report of the Joint Expedition of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the American School of Prehistoric Research, 1929-1934. Vol. 2. Clarendon Press.