Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

| Serbian Cyrillic alphabet Српска ћирилица, Srpska ćirilica | |

|---|---|

Serbian Cyrillic alphabet | |

| Script type | |

Period | 10th century – present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Official script | Serbia Montenegro Bosnia and Herzegovina Greece (Mount Athos, Hilandar Monastery) |

| Languages | Serbian Bosnian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs[1]

|

Child systems | Macedonian alphabet (partly) Montenegrin Cyrillic alphabet (partly) |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrl (220), Cyrillic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cyrillic |

| Subset of Cyrillic (U+0400–U+04FF) | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet (Serbian: Српска ћирилица, Srpska ćirilica, IPA: [sr̩̂pskaː t͡ɕirǐlitsa]), also known as the Serbian script,[2][3][4] (Српско писмо, Srpsko pismo, Serbian pronunciation: [sr̩̂psko pǐːsmo]), is a standardized variation of the Cyrillic script used to write the Serbian language. It originated in medieval Serbia and was significantly reformed in the 19th century by the Serbian philologist and linguist Vuk Karadžić.

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet is one of the two official scripts used to write modern standard Serbian, the other being Gaj's Latin alphabet.

Karadžić based his reform on the earlier 18th-century Slavonic-Serbian script. Following the principle of "write as you speak and read as it is written" (piši kao što govoriš, čitaj kao što je napisano), he removed obsolete letters, eliminated redundant representations of iotated vowels, and introduced the letter ⟨J⟩ from the Latin script. He also created new letters for sounds unique to Serbian phonology. Around the same time, Ljudevit Gaj led the standardization of the Latin script for use in western South Slavic languages, applying similar phonemic principles.

As a result of these parallel reforms, Serbian Cyrillic and Gaj’s Latin alphabet have a one-to-one correspondence. The Latin digraphs Lj, Nj, and Dž are treated as single letters, just as their Cyrillic counterparts are.

The reformed Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was officially adopted in the Principality of Serbia in 1868 and remained the sole official script into the interwar period. Both scripts were recognized in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During the latter period, Gaj’s Latin alphabet gained greater prominence, especially in urban and multiethnic contexts.

Today, both scripts are in official use for Serbian. In Serbia, Cyrillic has the constitutional status of "official script", while the Latin script is designated as "script in official use" for minority and practical purposes. Cyrillic is also an official script in Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, alongside the Latin alphabet.

Official use

[edit]Serbian Cyrillic is in official use in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[5] Although Bosnia and Herzegovina officially recognizes both the Cyrillic and Latin scripts,[5] the Latin alphabet is predominantly used in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[5] while Cyrillic is more commonly used in Republika Srpska.[5][6] In Croatia, the Serbian language is officially recognized as a minority language, and the use of Serbian Cyrillic is legally protected in areas with significant Serbian populations. However, the use of Cyrillic on bilingual signs has provoked protests and acts of vandalism in some communities.

Serbian Cyrillic is widely regarded as a key symbol of Serbian national and cultural identity.[7] In Serbia, all official documents are printed in Cyrillic only,[8] even though, according to a 2014 survey, 47% of Serbian citizens reported primarily using the Latin script, while 36% reported using Cyrillic.[9]

Modern alphabet

[edit]

The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, along with the equivalent forms in the Serbian Latin alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) value for each letter. The letters do not have names, and consonants are normally pronounced as such when spelling is necessary (or followed by a short schwa, e.g. /fə/).:

|

|

Summary tables

| A | a | B | b | C | c | Č | č | Ć | ć | D | d | Dž | dž | Đ | đ | E | e | F | f | G | g | H | h | I | i | J | j | K | k |

| А | а | Б | б | Ц | ц | Ч | ч | Ћ | ћ | Д | д | Џ | џ | Ђ | ђ | Е | е | Ф | ф | Г | г | Х | х | И | и | Ј | ј | К | к |

| L | l | Lj | lj | M | m | N | n | Nj | nj | O | o | P | p | R | r | S | s | Š | š | T | t | U | u | V | v | Z | z | Ž | ž |

| Л | л | Љ | љ | М | м | Н | н | Њ | њ | О | о | П | п | Р | р | С | с | Ш | ш | Т | т | У | у | В | в | З | з | Ж | ж |

| А | а | Б | б | В | в | Г | г | Д | д | Ђ | ђ | Е | е | Ж | ж | З | з | И | и | Ј | ј | К | к | Л | л | Љ | љ | М | м |

| A | a | B | b | V | v | G | g | D | d | Đ | đ | E | e | Ž | ž | Z | z | I | i | J | j | K | k | L | l | Lj | lj | M | m |

| Н | н | Њ | њ | О | о | П | п | Р | р | С | с | Т | т | Ћ | ћ | У | у | Ф | ф | Х | х | Ц | ц | Ч | ч | Џ | џ | Ш | ш |

| N | n | Nj | nj | O | o | P | p | R | r | S | s | T | t | Ć | ć | U | u | F | f | H | h | C | c | Č | č | Dž | dž | Š | š |

Early history

[edit]

Early Cyrillic

[edit]According to tradition, the Glagolitic script was created in the 860s by the Byzantine Christian missionaries Cyril and Methodius, during the period of the Christianization of the Slavs. The Glagolitic alphabet is considered the older of the two Slavic scripts and may have existed in some form before the official adoption of Christianity, though it was formalized and systematized by Cyril to represent Slavic sounds not found in Greek.

The Cyrillic script gradually replaced Glagolitic over the following centuries. It was likely developed by the disciples of Cyril and Methodius, possibly at the Preslav Literary School in the First Bulgarian Empire toward the end of the 9th century.[11]

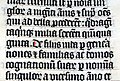

The earliest form of the Cyrillic script was known as ustav, a monumental script based on Greek uncial writing. It incorporated ligatures and additional letters adapted from the Glagolitic script to represent sounds not present in Greek. At this stage, there was no distinction between uppercase and lowercase letters. The literary language used was based on the Slavic dialect spoken in the region of Thessaloniki.[11]

Medieval Serbian Cyrillic

[edit]Part of the Serbian medieval literary heritage includes important works such as the Miroslav Gospel, Vukan Gospels, St. Sava's Nomocanon, Dušan's Code, and the Munich Serbian Psalter, among others. The first printed book in Serbian was the Cetinje Octoechos, published in 1494.

A notable feature of Serbian medieval writing, particularly associated with the Resava literary school, was the extensive use of diacritical signs and the use of the Djerv (Ꙉꙉ) to represent Serbian phonological reflexes of Proto-Slavic *tj and *dj — corresponding to the modern sounds [t͡ɕ], [d͡ʑ], [d͡ʒ], and [t͡ɕ]. Over time, these sounds were more systematically represented by the modern Serbian Cyrillic letters Dje (Ђђ) and Tshe (Ћћ).

Karadžić's reform

[edit]

During the Serbian Revolution, Vuk Stefanović Karadžić fled Serbia in 1813 and settled in Vienna, where he met Jernej Kopitar, a Slovene linguist and slavist. With the encouragement and support of Kopitar and Sava Mrkalj, Karadžić began reforming the Serbian language and its orthography. He finalized his reformed alphabet in 1818 with the publication of the Serbian Dictionary (Srpski rječnik).

Karadžić reformed the standard Serbian language and standardized the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet based on the phonemic principle of “write as you speak and read as it is written” (piši kao što govoriš, čitaj kao što je napisano), following the model of Johann Christoph Adelung and the influence of Jan Hus’s reforms of the Czech alphabet. His reforms modernized Serbian and moved it away from the older Church Slavonic tradition (particularly the Serbian recension and Russian Church Slavonic), bringing the literary language closer to the vernacular of the common people—specifically, the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect, which he spoke natively.

Karadžić, along with Đuro Daničić, was one of the principal Serbian signatories of the Vienna Literary Agreement in 1850. Encouraged by the Austrian authorities, this agreement laid the foundation for the modern standard literary language shared by Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, and Montenegrins, varieties of which are used in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia today.

Karadžić also translated the New Testament into Serbian, which was published posthumously in 1868.

He authored several influential books during the reform process, including Mala prostonarodna slaveno-serbska pesnarica and Pismenica serbskoga jezika (1814), followed by additional works in 1815 and 1818, while the alphabet was still being developed. In his letters from 1815 to 1818, Karadžić occasionally used archaic letters such as Ю, Я, Ы, and Ѳ, though he had already dropped Ѣ by the time of his 1815 songbook.[12]

The reformed Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was officially adopted in 1868, four years after his death.[13]

From the Old Church Slavonic script, Vuk Karadžić retained the following 24 letters:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

He adopted one letter from the Latin alphabet:

| Ј ј |

He also created five new letters to represent specific Serbian phonemes:

| Ђ ђ | Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Џ џ |

The following archaic letters were removed from use:

| Ѥ ѥ (je) | Ѣ ѣ (jat) | І ї (i) | Ѵ ѵ (i) | Оу оу (u) | Ѡ ѡ (o) | Ѧ ѧ (little yus) | Ѫ ѫ (big yus) | Ы ы (yery, hard i) | |

| Ю ю (ju) | Ѿ ѿ (ot) | Ѳ ѳ (th) | Ѕ ѕ (dz) | Щ щ (št) | Ѯ ѯ (ks) | Ѱ ѱ (ps) | Ъ ъ (hard sign) | Ь ь (soft sign) | Я я (ja) |

Modern history

[edit]

Austria-Hungary

[edit]Orders issued on 3 and 13 October 1914 prohibited the use of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, restricting its use solely to religious instruction. A decree issued on 3 January 1915 extended the ban to all public use of Serbian Cyrillic. Furthermore, an imperial order dated 25 October 1915 banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the sole exception of usage "within the scope of Serbian Orthodox Church authorities."[14][15]

World War II

[edit]In 1941, the Independent State of Croatia, a puppet state established by Nazi Germany, banned the use of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet.[16] The use of Cyrillic had already been restricted by regulations issued on 25 April 1941.[17] In June 1941, the regime began purging so-called "Eastern" (i.e. Serbian) words from the Croatian language and closed Serbian schools.[18][19]

Separately, the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet served as the foundation for the development of the modern Macedonian alphabet through the work of Krste Misirkov and Venko Markovski.

Yugoslavia

[edit]The Serbian Cyrillic script was one of the two official scripts used to write Serbo-Croatian in Yugoslavia from its establishment in 1918, alongside Gaj's Latin alphabet (latinica).

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Serbian Cyrillic ceased to be used at the national level in Croatia. However, it has remained an official script in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro.[20]

Contemporary period

[edit]Under the Constitution of Serbia adopted in 2006, the Cyrillic script is defined as the sole official script for use in government and official communication.[21]

Special letters

[edit]

The following typographical ligatures were developed specifically for the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet:

| Ђ ђ | Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Џ џ |

- Vuk Stefanović Karadžić based the letters Љ and Њ on earlier designs by Serbian linguist, grammarian, and philologist Sava Mrkalj, who attempted to reform the Serbian language before Karadžić. These letters were created by combining Л (L) and Н (N) with the soft sign (Ь).

- The letter Џ was derived by Karadžić from the letter "Gea" used in older forms of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet.[citation needed]

- Ћ was introduced by Karadžić to represent the voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate (IPA: /tɕ/). It was based on, though visually distinct from, the Glagolitic letter Djerv, which had historically represented various palatalized consonants such as /ɡʲ/, /dʲ/, and /dʑ/.

- The letter Ђ was designed by Serbian poet, prose writer, polyglot, and Orthodox bishop Lukijan Mušicki. Karadžić adopted this design, which was based on his own earlier modification of Ћ.

- The letter Ј was borrowed from the Latin alphabet, likely chosen by Karadžić in preference to the similar-looking Й used in other Cyrillic alphabets.

Differences from other Cyrillic alphabets

[edit]

Serbian Cyrillic differs from other Slavic Cyrillic alphabets by omitting several letters. It does not use the hard sign (ъ) or soft sign (ь), due to the absence of a phonemic distinction between iotated and non-iotated consonants. Instead, it employs unique letters that historically arose as ligatures. It also lacks letters such as Russian/Belarusian Э, Ukrainian/Belarusian І, the semivowels Й and Ў, and the iotated vowels Я (ya), Є (ye), Ї (yi), Ё (yo), and Ю (yu). These sounds are instead represented using digraphs with Ј, as in Ја, Је, Ји, Јо, Ју. The letter Ј also functions as a semivowel, replacing Й. The letter Щ is not used in Serbian; when necessary, it is transliterated as ШЧ, ШЋ, or ШТ.

Serbian italic and cursive forms of certain lowercase Cyrillic letters—б, г, д, п, т—differ significantly from their counterparts in Russian and other Cyrillic scripts. In the Serbian Cyrillic script, these letters take on distinct shapes: б, г, д, п, т. However, their upright (non-italic) forms are generally standardized across languages, with no officially recognized national variants.[22][23]

This poses challenges in Unicode rendering, as the italic variants are the only ones that differ, and Unicode assigns the same code points regardless of visual style. Professional Serbian typography addresses this through dedicated fonts, but most texts displayed on consumer devices use East Slavic (e.g., Russian) glyphs even when Serbian language codes are applied.

Some modern font families—such as those developed by Adobe,[24] Microsoft (from Windows Vista onward), and others[citation needed]—support Serbian-specific Cyrillic shapes in both regular and italic styles.

When supported by the font and rendering engine, correct glyphs can be displayed by marking text with appropriate language codes. For example:

<span lang="sr">бгдпт</span>produces Serbian forms: бгдпт<span lang="ru">бгдпт</span>produces Russian forms: бгдпт

In italic:

<span lang="sr" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>produces: бгдпт<span lang="ru" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>produces: бгдпт

Since Unicode does not distinguish between these national glyph variants at the character level,[25] font and language-tag support is required to render the correct form.

Keyboard layout

[edit]The standard Serbian keyboard layout for personal computers is as follows:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology, vol. 53, no. 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- ^ Sremac, Danielle S. War of Words: Washington Tackles the Yugoslav Conflict. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 1999. p. 59.

- ^ The Indian Journal of Politics. Aligarh Muslim University. Department of Political Science. 2000.

... who uses Serbian script ...

- ^ Exporters' Encyclopaedia. Dun and Bradstreet Publications Corporation. 1967. p. 528.

Serbian script is the Cyrillic (similar to the Russian script)...

- ^ a b c d Ronelle Alexander (15 August 2006). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-299-21193-6.

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella (15 January 2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-55070-4.

In addition, today, neither Bosniaks nor Croats, but only Serbs use Cyrillic in Bosnia.

- ^ Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. Brill. 13 June 2013. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

- ^ "Ćeranje ćirilice iz Crne Gore". Novosti.rs.

- ^ "Ivan Klajn: Ćirilica će postati arhaično pismo". B92.net. 16 December 2014.

- ^ Duret, Claude (1613). "Thrésor de l'histoire des langues de cest univers". Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b Cubberley, Paul (1996). "The Slavic Alphabets". In Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright (eds.), The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ^ The Life and Times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, p. 387

- ^ Vek i po od smrti Vuka Karadžića (in Serbian), Radio-Television of Serbia, 7 February 2014

- ^ Andrej Mitrović, Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918 p. 78–79. Purdue University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-55753-477-2, ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4

- ^ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780195333435.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 312–. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- ^ Enver Redžić (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. Psychology Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0.

- ^ Alex J. Bellamy (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester University Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6502-6.

- ^ David M. Crowe (13 September 2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-317-98682-9.

- ^ Yugoslav Survey. Vol. 43. Jugoslavija Publishing House. 2002. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ Article 10 of the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (English version Archived 2011-03-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- ^ Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.

- ^ "Adobe Standard Cyrillic Font Specification - Technical Note #5013" (PDF). 18 February 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ^ "Unicode 8.0.0 ch.02 pp. 14–15" (PDF).

Sources

[edit]- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). "Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries". Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Sir Duncan Wilson, The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, 1787-1864: literacy, literature and national independence in Serbia, p. 387. Clarendon Press, 1970. Google Books