Ashik

This article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (April 2020) |

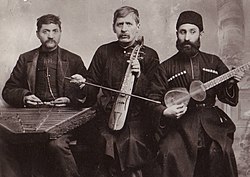

An ashik (Persian: آشیک; Azerbaijani: aşıq; Turkish: âşık) or ashugh (Armenian: աշուղ; Georgian: აშუღი)[1]: 1365 [2][3] is traditionally a singer-poet and bard who accompanies his song, be it a dastan (traditional epic story, also known as hikaye) or a shorter original composition with a long-necked lute, or an other instrument[4]: 225 in Armenian, Iranian, Azerbaijani, Turkish, South Azerbaijani[4] and Georgian cultures of the south caucasus and surrounding regions.[5]: 15–36 [6]: 47 [7][3] In general, the modern ashik is a professional musician who usually serves an apprenticeship, masters playing the duduk, saz, kamancheh, tar, or another instrument (like the sring or daf) and builds up a varied but individual repertoire of folk songs.[8][9]

Etymology

[edit]The word ashiq (Arabic: عاشق, meaning "in love" or "lovelorn") is the nominative form of a noun derived from the word ishq (Arabic: عشق, "love").[10] The term is synonymous with ozan in Turkish and Azerbaijani, which it superseded during the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries.[11]: 368 [12] Other alternatives include saz şair (meaning "saz poet") and halk şair ("folk poet"). In Armenian, the term gusan (գուսան), which referred to creative and performing artists in public theaters of ancient as well as medieval Armenia and Parthia, is often used as a synonym, as Armenian ashugs are the descendants of such groups.[5]: 20 [1]: 851–852

History

[edit]Ashugh tradition in Armenian culture

A concise account of the ashik (called ashugh in Armenian) music and its development in Armenia is given in Garland Encyclopedia of World Music.[1]: 851–852

In ancient Armenia, the predecessors of what now constitutes the ashugs, the gusans (գուսան), were singers, instrumentalists, dancers, storytellers, professional folk actors and the guardians of the Armenian language. The origin of Armenian religious and secular songs and their instrumental counterparts takes place in time immemorial. Songs arise from various expressions of Armenian folk art such as rituals, religious practices and mythological performances in the form of poetry, music, dance and theatre. Performers of these forms of expression, gradually honing their skills and developing theoretical aspects, have created a performing tradition. In ancient Armenia, musicians that were referred to as "vipasans” (storytellers) appeared in historical sources as early as the first millennium BC. Vipasans raised the art of secular song and music to a new level. Over time, the vipasans were replaced by "govasans" which later became known as "gusans.” The art of the latter is one of the most important manifestations of medieval Armenian culture, which left indelible traces in the consciousness and spiritual life of people. The word gusan appears in early Armenian written works, such as the Armenian translation of the Bible (5th century AD).[13] Gusans, cultivating this particular art form, created monumental works in both lyric and epic genres, thus enriching both national and international cultural heritage (such examples are the heroic epic “David of Sasun” and a series of lyric poems named hayrens).[14] The center of gusans was Goghtn, a region in the Vaspurakan province of Greater Armenia.[15]

In the early Middle Ages the word gusan was used as an equivalent to the ancient Greek word mimos (mime). There were 2 groups of gusans:

1. The first were from aristocratic dynasties (nakharars) and performed as professional musicians.

2. The second group comprised popular, but illiterate gusans.

Gusans wore long hair, combed up in a cone so that the hairstyle resembled the "tail" of a comet. This hairstyle was supported by a "gisakal" placed under it, which was the prototype of "onkos" - a triangle placed under the wig of ancient tragedians.[16]

The gusans were sometimes criticized and sometimes praised, particularly in medieval Armenia. The adoption of Christianity had its influence upon Armenian minstrelsy, gradually altering its ethical and ideological orientation. This led to the eventual replacement of gusans with ashugs around the 16th century.[17]

Many Armenian ashug arose since then. The first known Armenian ashug was Nahapet Kuchak, who was born during the early 16th century and died in the year 1592. He was known for his hayrens. The Armenian literary Arshag Chobanian collected and compiled over 400 of Kuchak's poems.[18]

The first popular Armenian ashug who was Naghash Hovnatan, a pioneering ashugh and painter from the 17th century who laid the groundwork for varied ashugh poetry. As a painter, Hovnatan undertook the interior decoration of the Etchmiadzin Cathedral in 1712, which was completed by 1721.[20] The nickname "naghash" means "painter" in Persian.[21]

The most popular ashug is Sayat-Nova, the legendary 18th-century ashug known for his iconic songs, creativity and poetic mastery. He has memorials placed for him in Georgia and Armenia.[22] The name Sayat-Nova has been given several interpretations. One version reads the name as "Lord of Song" (from Arabic sayyid and Persian nava) or "King of Songs". Others read the name as grandson (Persian neve) of Sayad or hunter (sayyad) of song.[23]

Another popular ashug is Jivani of the 19th century and early 20th century, who voiced the struggles of the Armenian people through powerful folk lyrics.[24] Sheram, is an ashug who bridged traditional and modern Armenian music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, while Havasi, was known for his emotional and nationalist songs; and Ashot, a 20th-century ashugh preserved and revitalized the tradition in Soviet Armenia.[25]

Ashik tradition in Turkic cultures

The ashik tradition among Turkic and Turkic-speaking humans of what is now Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Iran has its origin in pre-Islamic shamanism.[26] The ancient ashiks were called by various names such as bakshy (bakhshi, baxşı), dede, and uzan or ozan. Among their various roles, they played a major part in the perpetuation of the oral tradition, promotion of the communal value system and traditional culture of their people. These wandering bards or troubadours are part of the current rural and folk culture of Azerbaijan, Iranian Azerbaijan, Turkey and Turkmenistan. Thus, traditionally, ashik may be defined as travelling bards who sang and played the saz, an eight- or ten-string plucked instrument in the form of a long-necked bağlama.

Judging based on the Book of Dede Korkut,[27] the roots of Turkic ashiks can be traced back to the 7th or 14th century, during the heroic age of the Oghuz Turks. This nomadic tribe journeyed westwards through Central Asia from the 9th century onward and settled in what is now Turkey, Azerbaijan, and the northwestern areas of Iran. Their music evolved during their migration and ensuing feuds with the original inhabitants of the acquired lands. A component of this cultural evolution was when the Turks converted to Islam. Dervishes, desiring to spread the religion among their people who had not yet entered the Islamic cult, moved among the nomadic Turks. They chose the folk language and its associated musical form as an appropriate medium to transmit their messages. Ashik literature developed alongside Sufi culture and was still intact during the time of Ahmad Yasawi in the early twelfth century.[28]

A rather important events in Turkic ashik music was the ascent to the Iranian throne of the Shi'i leader Ismail I (1487–1524), the founder of Safavid Iran. He was a prominent poet and ruler whose followers. The Safavid order, believed him to be divine. In addition to his diwan, he compiled a mathnawi called the Deh-name, consisting of some eulogies of Ali. He used the pen-name Khata'i and with his poetry, he managed to inspire multiple ashik.[29] He did not only write in Persian, but also Turkic, due to his close ties to the qizilbash, who constituted the bulk of his army. Ismail praised playing saz as a virtue in one of his renowned qauatrains.[30]

According to Mehmet Fuat Köprülü's studies, the term ashik was used instead of ozan in what now constitutes Azerbaijan, Iran and parts of Anatolia after the 15th century.[31][32] After the demise of the Iranian Safavid dynasty in Iran, the Turkic language could not sustain its early development among the elites. Instead, there was a surge in the development of verse-folk stories, mainly intended for performance by ashiks in weddings. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union the governments of new republics in the Caucasus region and Central Asia sought their identity in traditional cultures of their societies. This elevated the status of ashiks as the guardians of national culture. The newfound unprecedented popularity and frequent concerts and performances in urban settings have resulted in rapid innovative developments aiming to enhance the urban-appealing aspects of ashik performances.

In September 2009, Ashiqs of Azerbaijan was included into UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.[33]

Ashik music in Iranian Azerbaijan

[edit]

During the Pahlavi era Ashiks frequently performed in coffee houses in all the major cities of east and west Azerbaijan in Iran. Tabriz was the eastern center for the ashiks and Urmia the western center. In Tabriz ashiks most often performed with two other musicians, a balaban player and a qaval player; in Urmia the ashik was always a solo performer.[34]

The foundations of ashik art

[edit]Musical instruments

[edit]

[[File:Aserbaidschanische Volksinstrument Saz.JPG|thumbnail|right|200px|Bağlama (saz)[[File:2 Kamānches, Persia, ca. 1880.jpg|thumb|Two kamanchehs]]

]]

Mastering playing saz, duduk, kamancheh, tar, or another instrument (like the sring or daf) is the essential requirement for an ashik. The saz, is a variant of the bağlama, a stringed musical instrument and belongs to the family of long-necked lutes.[35] While the duduk is a double reed woodwind instrument made of apricot wood.[36] The kamancheh is a bowed string instrument,[37] while the sring is a type of end-blown flute.[38] Performances of ashiks are sometimes accompanied by an ensemble of balaban/duduk/duduki[39] and daf performers.[40]

Poetry genres

[edit]The most spread poetry genres in Armenian ashug tradtion are Սիրային երգեր (Love songs), Դասական քնարերգություն (Classical lyrical poetry), Ծաղրերգություն (Satirical songs), Հերոսական / Պատմական երգեր (Heroic and historical songs), Ձոններ (Dedications / Panegyrics), Փիլիսոփայական երգեր (Philosophical/Reflective songs), Խոսք երգով (Dialogue songs/Musical Debates), Ողբեր (Laments/Elegies mourning sad events),Պարային երգեր (Dance songs).[41] [42] While poetry genres in Turkic ashug tradition are similar in many aspects, while gerayly, qoshma and tajnis also exist.[43][44]

Ethical code, behaviour and attitude of the ashiks

[edit]The defining characteristic of the ashik/ashug profession, the ethical code, behaviour and attitude was often dicussed, or explained by multiple ashugs. The ashug was not merely a singer or poet, but a moral voice and spiritual guide. Through their music, ashughs shaped public values, taught humility, and uplifted hearts. Their role demanded more than talent — it required wisdom, integrity, and deep respect for language and truth.

Ashughs like Sayat-Nova and Nahapet Kuchak wove ethical teachings into their verses. Their songs emphasized inner purity, proper conduct, and the power of words to inspire rather than harm. As one fragment from a poem of Sayat-Nova expresses:

Մարդ պիտի ըլլաս՝ արի՞ք, մեծահԱր է,

Խոսքդ խրհրդմամբ լեցուն, քո հոգին մաքրի՛ց։

Be a person of courage and nobility; let your words be full of wisdom, and purify your soul.

This reflects the moral compass of the ashugh tradition:[45][46][47]

- Speak with purpose.

- Live with humility.

- Serve truth through song.

- Let art be a path to virtue.

This has also been summarized by Aşiq Ələsgər in the following verses;[48][49]

Aşıq olub diyar-diyar gəzənin ----(To be a bard and wander far from home)

Əzəl başdan pürkəmalı gərəkdi --- (You knowledge and thinking head must have.)

Oturub durmaqda ədəbin bilə --- (How you are to behave, you too must know,)

Mə'rifət elmində dolu gərəkti --- (Politeness, erudition you must have.)

Xalqa həqiqətdən mətləb qandıra --- (He should be able to teach people the truth,)

Şeytanı öldürə, nəfsin yandıra --- (To kill evil within himself, refrain from ill emotions,)

El içinde pak otura pak dura --- (He should socialize virtuously)

Dalısınca xoş sedalı gərəkdi --- (Then people will think highly of him)

Danışdığı sözün qiymətin bilə --- (He should know the weight of his words,)

Kəlməsindən ləl'i-gövhər tokülə --- (He should be brilliant in speech,)

Məcazi danışa, məcazi gülə --- (He should speak figuratively,)

Tamam sözü müəmmalı gərəkdi --- (And be a politician in discourse.)

Arif ola, eyham ilə söz qana --- (Be quick to understand a hint, howe'er,)

Naməhrəmdən şərm eyleyə, utana --- (Of strangers you should, as a rule, beware,)

Saat kimi meyli Haqq'a dolana --- (And like a clock advance to what is fair.)

Doğru qəlbi, doğru yolu gərəkdi --- (True heart and word of honour you must have.)

Ələsgər haqq sözün isbatın verə --- (Ələsgər will prove his assertions,)

Əməlin mələklər yaza dəftərə --- (Angels will record his deeds,)

Her yanı istese baxanda göre --- (Your glance should be both resolute and pure,)

Teriqetde bu sevdalı gerekdi --- (You must devote himself to righteous path.)

Ashik art combines poetic, musical and performance ability. Some Ashiks themselves describe the art as the unified duo of saz and söz (word). This duo is conspicuously featured in a popular composition by Səməd Vurğun from the 20th century:[50]

Binələri çadır çadır --- (The peaks rise up all around like tents)

Çox gəzmişəm özüm dağlar --- (I have wandered often in these mountains)

İlhamını səndən alıb --- (My saz and söz take inspiration)

Mənim sazım, sözüm dağlar. --- (From you, mountains.)

The following subsections provide more details about saz and söz.

Ashik stories

[edit]

İlhan Başgöz was the first to introduce the word hikaye into the academic literature to describe ashik stories.[51] According to Başgöz, hikaye cannot properly be included in any of the folk narrative classification systems presently used by Western scholars. Though prose narrative is dominant in a hikaye, it also includes several folk songs. These songs, which represent the major part of Turkish folk music repertory, may number more than one hundred in a single hekaye, each having three, five or more stanzas.[52]

As the art of ashik is based on oral tradition, the number of ashik stories can be as many as the ashiks themselves. Throughout the centuries of this tradition, many interesting stories and epics have thrived, and some have survived to our times. The main themes of the most ashik stories are worldly love or epics of wars and battles or both.

In the following we present a brief list of the most famous hikayes/epics:[53]

- Daredevils of Sassoun (Armenian: Սասնա ծռեր Sasna cṙer) is an Armenian heroic epic poem in four cycles (parts), with its main hero and story better known as David of Sassoun, which is the story of one of the four parts.[54] This oral folk epic passed down for over a thousand years and was finally written down in 1873. It’s a heroic tale of four generations of warriors from the city of Sasun (in historic Western Armenia) who fight for freedom, justice, and honor, often against foreign invaders and tyrants to defend their homeland and their people. The performance of the Daredevils of Sassoun was included in the UNESCO Intangible cultural heritage representative list in 2012.[55][56]

- The Epic of Köroğlu is one of the most widespread of the Turkic hikayes. It is shared not only by nearly all Turkic people, but also by some non-Turkic neighboring communities, such as the Armenians, Georgians, Kurds, Tajiks, and Afghans.[57] In the Azeri version, the epic combines the occasional romance with Robin Hood-like chivalry. Köroğlu, is himself an ashik, who punctuates the third-person narratives of his adventures by breaking into verse: this is Köroğlu. This popular story has spread from Anatolia to the countries of Central Asia somehow changing its character and content.[8]

- The Legend of Akhtamar (Armenian: Ախթամարի լեգենդը) is a well-known Armenian folk tale associated with Akhtamar Island on Lake Van. The story centers around Princess Tamar, the daughter of the local king, and her secret love. According to the legend, Princess Tamar fell deeply in love with a young man who lived on the mainland. To be near him, she lit a lamp each night on the island’s church tower, guiding her lover across the dark waters of Lake Van. This nightly ritual became a symbol of their devoted love. However, Tamar’s father disapproved of their relationship. Upon discovering the secret meetings, he killed the young man, causing Tamar immense grief. Overcome with sorrow, she threw herself into Lake Van and drowned. The island of Akhtamar and its famous medieval Armenian church remain as a lasting monument to the tragic tale. The phrase “Akh, Tamar!” (“Oh, Tamar!”) is often uttered by locals, expressing mourning for the princess’s fate. The legend symbolizes themes of love, loss, and eternal devotion and holds an important place in Armenian cultural heritage.[58][59]

- Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid empire, is the protagonist of a major hikaye. Despite the apparent basis in history, Shah Ismail's hikaye demonstrates a remarkable transformative ability. Feared as a ruthless despot during his lifetime, Shah Ismail becomes a poetic maestro in the hikaye, with his sword replaced by his saz, which is the weapon of choice for Shah Ismail's new persona of folk hero.[60]

- The legend of Ara the Handsome (Armenian: Արա Գեղեցիկ, romanized: Ara Gełec‘ik) is one of the most famous Armenian legends, blending heroism, beauty, and tragedy. It dates back to pre-Christian Armenia and is centered around the legendary Armenian king Ara, known for his striking beauty. According to the legend, there lived a king in Armenia named Ara the Handsome, who was so beautiful that tales of his looks spread across kingdoms. In Assyria, the powerful Queen Semiramis (Armenian: Շամիրամ, Shamiram) heard of Ara and became obsessed with him. She sent messengers asking him to marry her, promising riches and power, but Ara, already married and faithful to his queen, refused her offer. Infuriated by the rejection, Semiramis declared war on Armenia, hoping to capture Ara alive and force him to love her. A battle ensued, and despite her orders not to harm Ara, he was killed in combat. Crushed by his death, Semiramis refused to believe he was truly gone. In some versions, she laid his body in a sacred place and prayed to the gods to resurrect him. In other versions, she called on sorcerers to bring him back to life. When that failed, she found a man who resembled him, dressed him in royal garments, and declared that Ara had risen.[61][62]

- Ashiq Qərib, Azeri epic, made famous by Mikhail Lermontov, is another major story of a wandering ashik who began his journeys with worldly love and attains wisdom by traveling and learning then achieving sainthood. The story of Ashiq Qərib has been the main feature of a movie with the same name by director and producer Sergei Parajanov.[63] In early 1980s Aşıq Kamandar narrated and sang the story in a one-hour-long TV program, the cosset record of which was widely distributed in Iranian Azerbaijan and had a key impact on the revival of ashug music.

- The legend of Hayk (Armenian: Հայկ, Armenian pronunciation: [hajk]), also known as Hayk Nahapet (Հայկ Նահապետ, Armenian pronunciation: [hajk nahaˈpɛt], lit. 'Hayk the Patriarch'), is one of the foundational myths of the Armenian people, a story that blends heroism, rebellion, and national identity. According to the legend, ater the fall of the Tower of Babel, a powerful warrior named Hayk, descendant of Noah’s son Japheth, refused to live under the rule of the tyrant Bel of Babylon. Seeking freedom, Hayk led his people north to the Armenian Highlands. But Bel pursued him with an army. Near Lake Van, Hayk turned and faced the invaders. With his mighty bow, he shot an arrow straight through Bel’s heart, killing him and scattering his army. Victorious, Hayk founded a new land, Hayastan, and his people became known as Hay. To this day, Armenians see Hayk as their legendary ancestor and a symbol of freedom, strength, and national identity.[64][65][66][67]

- Aşıq Valeh is the story of a debate between Aşıq Valeh[68] (1729–1822) and Aşıq Zərniyar. Forty ashiks have already lost the debate to Aşıq Zərniyar and have been imprisoned. Valeh, however, wins the debate, frees the jailed ashiks and marries Zərniyar.

Verbal dueling

[edit]In order to stay in the profession and defend their reputation ashiks used to challenge each other by indulging in verbal duelings, which were held in public places. In its simplest form one ashik would recite a riddle by singing and the other had to respond by means of improvisation to the verses resembling riddles in form. Here is an example:[69]

| The first ashik | The second ashik |

|---|---|

| Tell me what falls to the ground from the sky? | Rain falls down to the ground from the sky |

| Who calms down sooner of all? | A child calms down sooner of all. |

| What is passed from hand to hand? | Money is passed from hand to hand |

| The second ashik | Shik |

|---|---|

| What remains dry in water? | Light does not become wet in water |

| Guess what does not become dirty in the ground? | Only stones at the pier remain clean. |

| Tell me the name of the bird living alone in the nest | The name of the bird living in its nest in loneliness is heart. |

Famous ashiks

[edit]21st century

[edit]- Changiz Mehdipour, an Iranian ashik born in Sheykh Hoseynlu, has significantly contributed to the revival and development of ashik music. His book on the subject[70] attempts to adapt the ashik music to the artistic taste of the contemporary audience.

- Raffi (Rafik Garnik Hakobian) (Armenian: Ռաֆֆի (Ռաֆիկ Գառնիկ Հակոբյան) is an Armenian ashug born in 1960 inside the city of Yerevan. He studied vocal music and kamancha; later trained with the Sayat‑Nova ensemble. Hes been active from the 1980s onward, composing and performing ashugh songs such as “Dzon ashugh Jivanin”, “Hayutyan hatuk tesak”, and “Sayat‑Nova” . He has been recognized in the mid-2000s and is still active in traditional music circles.[71]

- Samira Aliyeva, born in Baku (1981), is a popular professional ashik who teaches at the Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art. She is committed to the survival of the ashik tradition.[72]

- Gevorg (Zhora Avetik Grigorian) (Armenian: Գևորգ (Ժորա Ավետիք Գրիգորյան), born 1965 in the Gegharkunik region. He studied mathematics and then music. He joined the Sayat‑Nova Ensemble in 1992. Hes known for songs like “Viravor hayduki yerge”, “Movses Georgisyan”, and “Tatul Krpeyanin” using a kamancha singing style .[71]

- Zulfiyya Ibadova, born in 1976, is a passionate and vibrant performer with a strong individual style. She has written a great deal of original music and lyrics, and likes combining the Saz with other instruments.[72]

- Mkhitar (Mkhitar Vladimir Kettsian) (Armenian: Մխիթար (Մխիթար Վլադիմիր Քեթցյան), was born 1972 in Dilijan. He studied music from youth at the Jivani School of Minstrel Art, joined the Sayat‑Nova Ensemble in 1994. He also won the first prize at the 2003 All‑Armenian Sayat‑Nova Competition performing “Yerb khognem“. Hes also known for songs like “Im mayrik” and “Khosir, angin”.[71]

- Fazail Miskinli, born in 1972, is a master Saz player. He teaches at the Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art.[73]

- Nazeli (Nazik Lentush Grigorian) (Armenian: Նազելի (Նազիկ Լենտուշ Գրիգորյան) was born 1965 in the Tavush region. He studied philology at Yerevan State University and Jivani Ashugh School. He became an officially recognized Ashugh Master in 2013. Popular songs include “Im surb matur”, “Karmir vardi aln em sirum”, and “Mosh achqer”.[71]

20th century

[edit]- Turkish ashug of this era: Ali Ekber Chichek, Ashik Ibreti, Ashik Khanlar, Ashik Mubarak Yaafar, Muhlis Akarsu, Ashik Daimi, Ashig Hossein Bozalganly, Ashig Hossein Sarajly, Ashig Mikayil Azafly, Ashig Emrah

- Ashugh Havasi (Armenak Parsam Markosyan) (Armenian: Աշուղ Հավասի (Արմենակ Պարսամի Մարկոսյան)was a blind Armenian ashugh born in 1896 in the village of Ayazma (Javakheti, Georgia). He lost his eyesight at age 3 due to smallpox but began learning ashugh art at the age of 12 from his master Tifili, who gave him the name “Havasi,” meaning “mood” or “feeling.” He began performing professionally in 1914 and moved to Yerevan in 1945, where he became one of the most beloved Soviet Armenian ashughs. He joined the Writers’ and Composers’ Unions and was awarded the title People’s Artist of the Armenian SSR in 1967. Havasi composed over 3,000 poems and hundreds of songs and ballads. His works, like «Եղնիկի պես» (“Like a Deer”) and «Ի՞նչ ասեմ յարիս» (“What Shall I Tell My Beloved”), are known for their lyrical beauty and emotional depth. He died in 1978 in Yerevan, leaving a lasting legacy in the Armenian ashug-scene. Below is his well-known song «Եղնիկի պես» (Like a Deer):[74]

Ալ երեսդ ալա է,

Բացված կարմիր լալա է,

Նայվածքդ, սիրուն աղջիկ,

Գլխիս դարդ ու բալա է։

Եղնիկի պես ծուռ մի աշե, սիրո՛ւն ջան,

Ջահել սիրտս դու մի մաշե, սիրու՛ն ջան։

Your face is bright as dawn,

A red tulip has opened,

Your gaze, lovely maiden,

Is both sorrow and joy upon my head.

Like a deer be graceful, my love,

You soften my youthful heart, my love.

- Neshet Ertash, was a Turkish ashug born in 1938 in Kirshehir, and started playing baglama since he was 5. He died on 25 September 2012 in Izmir.[75] The opening quatrain of his composition, Yalan Dünya, is as the following:[76]

Hep sen mi ağladın hep sen mi yandın, --- (Did you cry all the time, did you burn all the time?)

Ben de gülemedim yalan dünyada --- (I couldn't smile too in untrue world)

Sen beni gönlümce mutlu mu sandın --- (Did you think I was happy with my heart)

Ömrümü boş yere çalan dünyada. --- (In the world which stole my life in vain")

- Gusan Shahen (Shahen Yeghiazari Sargsyan) (Armenian: Աշուղ Շահեն (Շահեն Եղիազարի Սարգսյան) was a major 20th-century Armenian gusan/ashug from Gyumri, Shirak. He studied music in Yerevan, performed with Soviet ensembles, and later founded groups like Shaheni Knary to promote ashugh art. He wrote over 500 songs, blending Shirak folk melodies with romantic and heroic themes. Shahen became People’s Artist of the Armenian SSR in 1967 and won a UNESCO prize in 1973. In 1982, he founded an ashugh school in Gyumri. The following excerpt is from his poetic song «Սովետական բաղի միջին» (“In the Soviet Garden”), praising beloved beauty:[77][78]

Սովետական բաղի միջին

Բուսել ես դու չինարի պես,

Աշուղ Շահեն, գեղեցկատես,

Գովական սիրունըդ տեսար,

Միշտ ծաղկած գարունըդ տեսար,

Արևից գեղեցիկ չըկա,

Արևն էլ չեղավ քեզի պես։

Amid the Soviet garden

You grew up like a poplar tree

Ashugh Shahen, beauty-surveyor,

He beheld your praise‑worthy loveliness,

Always your spring in bloom he saw

None as fair as sunshine,

Even the sun could not match you.

- Ashig Hossein Javan, born in Oti Kandi in Arasbaran, is an ashik who was exiled to the Soviet Union due to his revolutionary songs during the brief reign of the Azerbaijan People's Government following the World War II.[79] Hoseyn Javan's music, in contrast to the contemporary poetry in Iran, emphasizes on realism and highlights the beauties of real life. One of Hoseyn's songs, with the title "Kimin olacaqsan yari, bəxtəvər?", is among the most famous ashugh songs.

- Yeghishe Charents (Yeghishe Abgari Soghomonyan) (Armenian: Եղիշե Չարենց (Եղիշե Աբգարի Սողոմոնյան), born in 1897, was a leading Armenian poet of the 20th century. Born in Kars, he lived through war and revolution, which deeply shaped his work. His poetry blended Armenian tradition with modern styles like Futurism. Charents supported the early Soviet regime but later wrote more national and personal poetry. His famous work “The Land of Nairi” mourns and celebrates Armenia. In 1937, he was arrested during Stalin’s purges and died in prison. His legacy is honored today as a symbol of Armenian cultural identity. One of his poems «Աշուղ Սայաթ‑Նովի նման…» (“Like Ashugh Sayat‑Nova…”) reflecting ashugh traditions in modern Armenian literature, this is an excerpt from it:[80][81]

“Աշուղ Սայաթ‑Նովի նման՝ ես երգ ու տաղ պիտի ասեմ…”

He speaks of singing eternal songs like the classic ashugh himself.

- Kamandar Afandov was born in 1932 in Georgia. In early eighties Kamndar performed shortened version of famous hikayes intended for contemporary audience. These performances were effective in the revival of ashik music.[82]

- Ofelya Karapeti Hambardzumyan (Armenian: Օֆելյա Կարապետի Համբարձումյան), born in Yerevan on January 9, 1925 was a female Armenian folk singer and ashug. Recognized early for her voice, she studied at the Romanos Melikyan Musical College. In 1944, she became a soloist with the Folk Instrument Ensemble of Armenian Radio, led by Aram Merangulyan. Her repertoire included classical, folk, and ashughakan music. She was especially known for her interpretations of Sayat-Nova’s songs like "Յարէն էրուած իմ Yaren ervac im" and "Յիս կանչում եմ լալանին Yis kanchum em lalanin". She also performed works of Fahrad, Jivani, Sheram, and contemporary ashughs like Shahen, Havasi, and Ashot, often as their first performer. She died in Yerevan on June 13, 2016.[83][84]

- Rasool Ghorbani, recognized as a masters of ashugh music, was born in 1933 in Abbasabad. Rasool started his music career in 1952 and by 1965 was an accomplished ashik. Rasool had performed in international music festivals held in France, Germany, the Netherlands, England, Japan, China, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, Australia, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Turkey and Hungary.[85][86] Rasool has been awarded highest art awards of Iran,[87] and will be honored by government during the celebration for his 80th birthday.[88]

- Gusan Ashot (Ashot Hayrapeti Dadalyan) (Armenian: Գուսան Աշոտ (Աշոտ Հայրապետի Դադալյան), was a renowned Armenian gusan/ashug of the 20th century, born on April 25, 1907, in Goris. He grew up surrounded by folk music and learned to play traditional instruments like the duduk and sring, which deeply influenced his poetic and musical style. In 1958, he joined the Writers’ and Composers’ Union of Armenia, and in 1967, he was named People’s Artist of the Armenian SSR. He performed across Armenia and the Soviet Union, often with his own ensemble, and became known for heartfelt songs about love, nature, and village life. His most famous works include “Sari Sirun Yar”, “Odjakhum”, and “Sarvori Yergy”. Gusan Ashot passed away on February 20, 1989, in Yerevan, leaving behind a rich legacy that remains central to Armenian ashugh and gusan tradition. The following poem is an excerpt from «Սարի սիրուն յար» – “Beautiful Darling of the Mountains”:[89][90]

Սարի սիրուն յար, քեզի օր կըսեմ,

Սիրո սրտով եմ տենում ու կերթամ,

Աչքիդ շողերը բոց են իմ հոգում,

Քեզի մոռնալ չեմ կարող, յար ջան։

Քամին կբերի հուշեր սարերից,

Ձայնդ լսելու կարոտից մաշեմ,

Սարի սիրուն յար, գարուն իմ մենակ,

Քեզի չտեսնեմ՝ դարդից կը մերնեմ։

Beautiful darling of the mountains, I speak to you each day,

With a heart full of love, I gaze and walk away.

The light of your eyes burns deep in my soul.

To forget you, my love, is not something I can do.

- Ashik Mahzuni Sherif,(17 November 1940 – 17 May 2002), was a folk musician, ashik, composer, poet, and author from Turkey.[91] His had an undeniable contribution in popularizing ashik music in intellectual circles.[92] The opening quatrain of his composition, İşte gidiyorum çeşm-i siyahım, is as the following:[93]

İşte gidiyorum çeşm-i siyahım --- (That's it, I go my black eyed)

Önümüze dağlar sıralansa da --- (Despite mountains ranked before us)

Sermayem derdimdir servetim ahım --- (My capital is my sorrow, my wealth is my trouble)

Karardıkça bahtım karalansa da --- (Withal my blacken fortune darkened")

- Araksia Gyulzadyan (Armenian: Արաքսյա Կարապետի Գյուլզադյան) was a female Armenian ashug born on June 5, 1907, in Gyumri. Since her childhood she sang in church, later studying under composer Romanos Melikyan after moving to Yerevan in 1926. She became the principal female soloist for the Armenian Radio Orchestra of Folk Instruments, serving until 1955, and then as a soloist with the Armenian Philharmonic. Renowned for her rich, expressive voice, she is especially remembered for interpreting the ashugh Sheram’s songs, including classics like «Քեզանից մաս չունիմ», «Շորորա», and «Դուն իմ մուսան ես». In 1960, she was honored with the title People’s Artist of the Armenian SSR. She passed away in Yerevan on October 7, 1980, leaving behind a legacy as one of the first and greatest female performers in Armenian folk and ashugh music. The following poem is an excerpt from Araksias poetic song «Դուն իմ մուսան ես» (“You Are My Muse”):[94]

Դուն իմ մուսան ես, Առանց քեզի երգել չեմ կարող։

Սրտիս տավիղը Բացի քեզնից էլ չունիմ լարող։

Սիրուն սև աչերուդ, Կարմիր վարդ այտերուդ…

Դուն անգին զարդ ես…

You are my muse, without you, I cannot sing.

My heart’s instrument has no tuning outside of you.

Your lovely dark eyes, your rosy petals…

You are the priceless adornment…

- Ashik Veysel (25 October 1894 – 21 March 1973). The opening quatrain of his composition, Kara Toprak ("Black earth"), is as the following:[95]

19th century

[edit]

- Jivani (Armenian: Ջիվանի, 1846–1909), born Serob Stepani Levonian (Սերոբ Ստեփանի Լևոնյան), was an Armenian ashugh (or gusan) and poet.[96] He was an influential figure in 19th-century Armenian cultural life. He was born in the village of Kartsakhi near Akhalkalaki in the region of Javakheti (present-day Georgia). Orphaned early in life, he was raised in difficult conditions and studied under Master Ghazar, from whom he learned to play the kamancha and saz, foundational instruments in ashugh music. Jivani composed hundreds of songs and poems, focusing primarily on social and political issues such as poverty, injustice, inequality, and the oppression of the Armenian people. Rejecting romanticism, he gave voice to the struggles of the working class, using satire, allegory, and clear moral messages to critique authority and advocate for justice. His works, written in both classical Armenian and regional dialects, were accessible to a wide audience and carried a strong sense of national identity and social awareness. He traveled and performed across the South Caucasus, including in Tiflis, Yerevan, and Shusha, participating in literary gatherings and poetic contests. His performances earned him great respect among Armenians and other ethnic communities. Jivani spent his later years in Tiflis, where he died in 1909. His legacy continues through his widely preserved songs, which remain central to Armenian folk music. He is commemorated by schools, streets, and cultural institutions bearing his name, and his influence endures in the works of both traditional and contemporary Armenian musicians. Jivani's compositions, as said before, mostly deal with social issues. His poem Unhappy days (Ձախորդ օրերը) highlights this:[97][98]

Ձախորդ օրերը ձմռան նման կուգան ու կերթան,

Վհատելու չէ, վերջ կունենան, կուգան ու կերթան։

Դառն ցավերը մարդու վերա չեն մնա երկար,

Ո~րքան հաճախորդ շարվեշարան կուգան ու կերթան։

Over the heads of nations persecutions, troubles, woes,

Pass—like caravans along the road—they come and go.

The world is like a garden, and men are like its flowers;

How many roses, violets, balsam—come and go.

- Ashiq basti (1836–1936) was one of the prominent female representatives of the Azerbaijani-speaking ashig in 19th-century. She had good knowledge about folk literature and recited her own poems at folk gatherings. she also learned to play the saz and took part in gurban bulaghi, a rather well-known literary circle of the time. Between the ages of seventeen and eighteen, she fell in love with a shepherd named khanchoban, who was later killed by a nobleman in her presence. This event deeply affected her and became the subject of her poetry. An epic called basti and khanchoban was created around her story. She is said to have lost her sight from weeping and became known as “blind basti.” she lived to be 100 years old, passing away in 1936.[99]

- Sheram (Armenian: Շերամ, lit. 'silkworm', born Grigor Talian; 20 March 1857 – 7 March 1938) was an Armenian composer and bard (ashugh or gusan). A native of Gyumri, the center of the Armenian ashughs, he received no education and was a self-taught musician. He was one of several Armenian folk musicians who introduced simpler and lighter forms of music and lyrics. Many of his songs remain popular to this day. Influenced by the legacy of Jivani, Sheram developed a style that blended folk simplicity with lyrical emotion. He moved away from long and complex poetic forms and instead favored shorter, melodious, and accessible songs, often centered on themes of love, longing, homeland, and human feeling. His melodies were typically performed on traditional instruments like the tar, kemanche, and sring. Sheram composed over 1,000 songs, many of which are still performed today. Some of his best-known works include “Shogher Jan”, “Alagyaz”, “Im Anoush Davigh”, and “Gharabaghtsin”. His songs became especially popular in Soviet Armenia, where they were embraced as part of the national cultural heritage. He died in 1938, but his legacy lives on as one of the last great classical Armenian ashughs. The following excerpt is from one of his powms called “Shogher Jan” (Շողեր ջան).[100][101]

Շողեր ջան, գեթ մի գիշեր քուն չես եկել,

Հերքի պես իմ սրտին բոց ես եկել։

Թե քուն ես, տես ո՞ւմ երազուն ես եկել,

Թե արթուն ես՝ ինչու չես գալիս։

Shogher jan, not once have you come in my sleep,

Like a fever, into my heart you creep.

If you are asleep—whose dreams do you grace?

If you are awake—why not come to my place?

- Ashig Alasgar, perhaps the most renowned Azerbaijani ashik of all ages, was born in 1821 in the Gegharkunik Province (Գեղարքունիքի մարզ), specifically the village of Azat, that lies in Armenia to an impoverished family. At the age of 14 he was employed as a servant boy and worked for five years, during which fell in love with his employer's daughter, Səhnəbanı. The girl was married off to her cousin and Alasgar was sent home. This failed love urged young Alasgar to buy a saz and seek apprenticeship with Ashik Ali for five years. He emerged as an accomplished ashik and poet and in 1850, defeated his master in a verbal dueling. The rest of Alasgar's productive life was spent training ashiks and composing songs until his death in 1926.[102] One of his most popular poems is titled Deer (Jeyran).[103] The song has been recently performed by the Azerbaijani singer Fargana Qasimova. Alim Qasimov offers the following commentary on this popular song: "In Azerbaijan, jeyran refers to a kind of deer that lives in the mountains and the plains. They’re lovely animals, and because their eyes are so beautiful, poets often use this word. There are many girls named Jeyran in Azerbaijan. We hope that when listeners hear this song, they’ll get in touch with their own inner purity and sincerity."[104]

Durum dolanım başına, --- (Let me encircle you with love,)

Qaşı, gözü qara, Ceyran! --- (Your black eyes and eyebrows, Jeyran.)

Həsrətindən xəstə düşdüm, --- (I have fallen into the flames of longing,)

Eylə dərdə çara, Ceyran! --- (Help me to recover from this pain, Jeyran".)

- Shirin (Armenian: Շիրին), born Hovhannes Karapeti Karapetyan (Armenian: Հովհաննես Կարապետի Կարապետյան) (June 11, 1827, Koghb, Erivan Khanate, Qajar Iran – July 30, 1857, Vagharshapat, Erivan uezd, Russian Empire), was a 19th-century Armenian ashugh (folk singer-poet). Active during a period of political transition from Persian to Russian rule in Eastern Armenia, Shirin’s songs reflected themes of love, nature, melancholy, and Armenian identity. His pen name “Shirin,” meaning “sweet” in Persian, was likely inspired by Persian literary tradition, which deeply influenced Armenian ashugh culture of the time. Though he died young at 30, Shirin was well-regarded among his contemporaries. His works were primarily transmitted orally, with only a few surviving fragments. He belonged to the same ashugh tradition that bridged earlier figures like Sayat-Nova and later ones such as Jivani. His legacy survives in regional memory and occasional anthologies of Armenian folk poetry.[105]

- Ashik Summani, Ashig Aly

18th century

[edit]

- Sayat-Nova (Armenian: Սայեաթ-Նովայ (сlassical), Սայաթ-Նովա (reformed); born Harutyun Sayatyan (Armenian: Հարություն Սայաթյան); 14 June 1712 – 22 September 1795) was an Armenian poet, musician and one of the most important and influential ashugh of all time. He was born in Tiflis (modern-day Georgia), a city that was then mostly populated by Armenians, but yet was a multicultural environment where Armenian, Georgian, Persian, and Turkic traditions blended. This diverse atmosphere deeply influenced his art. Though Armenian by origin, Sayat-Nova composed in four languages, Armenian, Georgian, Persian and what is now known as North Azerbaijani and other Turkic dialects, making him a symbol of cultural unity in the Caucasus. His pen name, often interpreted as “King of Songs” or “Hunter of Melodies,” reflects his poetic identity. Sayat-Nova served as a court musician to King Erekle II of Kartli-Kakheti, where he gained fame for his lyrical mastery and emotional depth. Sayat-Nova was skilled in writing poetry, singing, and playing the kamancheh, chonguri and tambur. His songs explore themes of love, spirituality, sorrow, and longing, blending Armenian folk tradition with Persian poetic forms like the ghazal. Sayat-Nova’s most beloved songs include Nazani, Kamancha, and Tamam Ashkharh (The Whole World). Many of his poems use rich metaphor and spiritual imagery, often elevating romantic love to the divine. Later in life, after leaving the royal court, possibly due to political or romantic conflicts, he became a priest in the Armenian Apostolic Church, serving in monasteries such as Haghpat and Sanahin. He continued to write religious poetry during this time. Sayat-Nova was killed during the Battle of Krtsanisi in the year of 1795 inside the village of Haghpat, reportedly for refusing to renounce Christianity. He is buried at the Armenian Cathedral of Saint George in Tbilisi. His legacy lives on in Armenian culture and across the region. He remains the most iconic ashugh in Armenian history, and his songs are still widely performed today. In 1969, Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov paid tribute to him with the celebrated film The Color of Pomegranates, a poetic interpretation of Sayat-Nova’s life and art. The following excerpt is from his famous poem Nazani (Նազանի):[106][107]

Նազանի, կարմիր նազանի,

Ձագն ունիս նաիր նազանի,

Թուխ աչքերդ կապեցին զիս,

Դուն ես իմ խելքիս հանցանի։

Զոր եմ նստում՝ դեմքդ գծեմ,

Անուշ լեզվով խոսքդ հիշեմ,

Սիրտս այրվի, հոգիս ելնի,

Դուն ես իմ խելքիս հանցանի։

Քանի պճեղ առնեմ ու զգամ,

Քան զեփյուռ փչեմ ու հոտ առնեմ,

Քան քու սեւ մազդ շոյեմ, դաշնամ,

Դուն ես իմ խելքիս հանցանի։

Nazani, my red Nazani,

You have the charm of a spring gazelle, Nazani.

Your dark eyes have enchanted me,

You are the reason I’ve lost my mind.

When I sit, I try to sketch your face,

I remember your sweet, tender words.

My heart burns, my soul wants to leave,

You are the reason I’ve lost my mind.

How often shall I caress and feel you?

Like a breeze, how often shall I breathe your scent?

How often shall I touch your black hair and play with it?

You are the reason I’ve lost my mind.

- Khasta Qasim, (1684–1760) was one of the most popular folk poets in Azerbaijan. Khasta, which he chose for a pen-name, means "one in pain".

- Paghdasar Tbir (Armenian: Պաղտասար Դպիր, born 7 June 1683 in Constantinople – died 1768 in Constantinople), was an Armenian ashug, poet, musician, scientist, printer, and a luminary of national and educational movements. He is considered a leading figure during the revitalization period of Armenian culture. Born in a time of political turmoil and foreign domination, Baghdasar dedicated his life to preserving and promoting Armenian heritage through his multifaceted talents. As an ashugh, he combined lyrical poetry with music, using his art to inspire and educate the Armenian people. His works often carried deep social commentary, addressing issues such as injustice, the plight of the common folk, and the corruption prevalent in society. Beyond his artistic contributions, Baghdasar was also a scientist and a printer, helping to advance Armenian education and literacy by participating in early printing efforts that made literature more accessible. His commitment to education and culture made him a pivotal figure in the Armenian national awakening, bridging the gap between traditional folk art and the emerging modern literary movements. Baghdasar Dpir’s legacy lives on as a testament to the power of art and knowledge in sustaining a nation’s identity during times of adversity.[108][109]

- Dadaloğlu, Zarnigar Derbentli

17th century

[edit]

- Naghash Hovnatan (Armenian: Նաղաշ Հովնաթան; 1661, Shorot, Nakhijevan, Safavid Iran – 1722, Shorot) was an Armenian poet, ashugh, painter, and founder of the Hovnatanian artistic family. He is considered the founder of the new Armenian minstrel school, following medieval Armenian lyric poetry. Bridging classical Armenian literary traditions with vernacular expression, Hovnatan laid the foundation for a revitalized ashugh culture that resonated deeply with the people of his time. His poetic works, often rich in satire, moral reflection, and emotion, marked a turning point in Armenian literature, as they moved away from purely ecclesiastical or courtly themes toward more accessible and realistic depictions of life. As an ashugh, Hovnatan composed songs that were performed with traditional instruments like the kamancha and tar, making his verses not only literary but also part of the living musical tradition. His work reflects themes such as love, vanity, faith, hypocrisy, and the impermanence of life, delivered with a distinct blend of lyricism and irony. Beyond poetry and music, Naghash Hovnatan was an accomplished painter. His artistic legacy survives in religious murals, including significant contributions to the decoration of the Etchmiadzin Cathedral, the spiritual center of the Armenian church. This combination of literary and visual art positioned him as a true Renaissance figure in the Armenian cultural revival under Safavid rule. Naghash Hovnatan’s influence extended through his descendants, giving rise to the Hovnatanian family of painters, who continued his artistic legacy across generations. Through both his poetry and visual art, Hovnatan helped shape a more expressive, people-centered Armenian culture in the early modern period, leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s literary and artistic history. The following poem is one of Hovanatans.[110][111][112][113]

Լուսնի նման պայծառ երես բոլորած,

Ես մնացի կարոտ՝ համբուրելու համար։

Վարսերդ ոսկի թելի նման ոլորած,

Ես մնացի կարոտ՝ զայն քանդելու համար։

Ունքերդ կապել է կամար կրակով,

Աչքերդ վառել է պայծառ ճրագով։

Ափսոս, որ ծածկել ես բարակ լաչակով,

Ես մնացի կարոտ՝ տեսնելու համար։

Your face shines bright, like the moon aglow,

I remain in longing—to give it a kiss.

Your hair, like threads of gold in a gentle flow,

I remain in longing—to untangle its twists.

Your brows are arched like a fiery bow,

Your eyes are lit like a radiant lamp.

Alas! You've veiled them, soft and low—

I remain in longing—to behold their stamp.

- Kul Nesîmî is a 17th century Turkish poet.

- Karacaoğlan is a 17th-century Ottoman folk poet and ashik, who was born around 1606 and died around 1680. The opening quatrain of his composition, Elif, is as the following:[114]

incecikten bir kar yağar, --- (With its tender flakes, snow flutters about,)

Tozar Elif, Elif deyi... --- (Keeps falling, calling out "Elif… Elif…”)

Deli gönül abdal olmuş, --- (This frenzied heart of mine wanders about)

Gezer Elif, Elif deyi... --- (Like minstrels, calling out "Elif… Elif…”)

- Ghazar Sebastatsi

- Aşıq Ümer (1621—1707) medieval Crimean Tatar poet from Kezlev. He wrote mainly lyric poems and greatly influenced the later ashiks.

- Ghazar Sebastatsi (Armenian: Ղազար Սեբաստացի, c. 1600 – c. 1675) was an Armenian ashug, poet, lyricist, and satirist from Sebastia (modern-day Sivas in central Anatolia). Active during the 17th century, he was one of the earliest figures to contribute to the transition from Middle Armenian literature to Modern Armenian vernacular poetry, blending lyrical, secular, and folk elements. He is considered one of the lesser-known but culturally significant Armenian poets of his century. Alongside other 17th-century writers like Martiros Ghrimetsi, Stepanos Dashtetsi, and Kosa Yerets, Ghazar played a role in shaping a new poetic voice that moved away from scholasticism and toward emotive expression, folk motifs, and accessible language. Ghazar’s poems often reflect themes of love, impermanence, the human condition, and satire, using metaphors typical of ashugh-style verses but with a sharper, more concise form. His legacy was preserved mostly through oral transmission and manuscript anthologies, where his name is sometimes attached to hairens and short lyrical pieces. While not as famous as Sayat-Nova or Naghash Hovnatan, he is still part of the early wave of Armenian vernacular poets who laid the groundwork for the ashugh tradition that would flourish in the 18th and 19th centuries. His cultural relevance lies not in innovation, but in preserving a voice of the time Armenians living under Ottoman rule, expressing personal and communal emotions through song. The following poem is an example of his love-poems:[115]

Աչքերդ նման են գիշերվա աստղերուն,

Ձայնդ մեղմ է, ինչպես հովը գարնան։

Սիրտս դողում է քո հայացքէն մեկից,

Սերիդ կարոտով հալչում եմ դարձյալ։

Your eyes are like the stars of night,

Your voice is gentle like the breeze of spring.

My heart trembles from a single glance of yours,

I melt again with longing for your love.

- Ashik Abbas Tufarganly was born in the late 16th century in Azarshahr. According to a popular ashik hikaye, known as Abbas və Gülgəz, he was a love rival of King Abbas. The facts about Ashik Abbas's life are mixed with the myths of the said hikaye. Ashik Abbas's compositions have survived and are still song by contemporary ashiks. A famous song starts as the following:[116][117]

Ay həzarət, bir zamana gəlibdir, --- (Oh brothers and sisters, what have we come to:)

Ala qarğa şux tərlanı bəyənməz --- (The jay hates the eagle as never before.)

Başına bir hal gelirse canım, --- If something happens to you,

Dağlara gel dağlara, --- Come to the mountains,

Seni saklar vermez ele canım, --- She will embrace you as her own,

Seni saklar vermez ele. --- Never hands you in to the strangers.

........

16th century

[edit]

- Nahapet Kuchak (Armenian: Նահապետ Քուչակ; died 1592) was a medieval Armenian poet and one of the earliest known ashughs in the Armenian tradition. He is especially remembered for his mastery of the hairen (հայրեն), a traditional Armenian poetic form consisting of four-line stanzas in 15-syllable meter, often focused on themes of love, longing, morality, and the beauty of nature. (Often described as „couplets with a single coherent theme“) His style, direct and emotional, made a deep impression on Armenian poetry and left a lasting influence on future generations of ashughs. Kuchak was likely born in the village of Kharakonis, located near the city of Van in the historical Armenian region of Vaspurakan. Little is known about his early life, but he married a woman named Tangiatun and spent his life in the Lake Van area. His poetry reflects a deeply personal, almost spiritual tone, often addressing the pains and joys of love, loneliness, and human dignity. Unlike many poets of his time, Kuchak rarely engaged in political or religious themes. Instead, he focused on the emotional and moral worlds of everyday people. He died in 1592 and was buried in the cemetery of the Kharakonis St. Theodoros Church. His grave later became a site of pilgrimage, visited by those who admired his verses and the honesty of his expression. Though he lived a modest life, his poems ensured his name would live on in the cultural memory of the Armenian people. Nahapet Kuchak is now considered a foundational figure in the development of the ashugh tradition. His influence can be seen in the works of later poets such as Sayat-Nova, Jivani, and Sheram, all of whom followed in his footsteps, blending lyricism with the Armenian oral and musical heritage. The following is an excerpt of one of his poems:[118][119][120][121]

Հոգիս մարմնից դուրս եկավ, նստեցի վիշտուն,

«Հոգիս, եթե թողնես ինձ՝ իմ առակը գուլ է» գոռացի ես:

Եվ հոգիս պատասխանի՝ «Որ գիտությունդ ո՞ր թաղեցիր,

Երբ տունդ փլուզվում է՝ ինչո՞ւր մնաս տերը դու՞»

My soul left my body, I sat down to lament: ‘My soul, if you leave me my life is spent!’ And my soul replied: ‘Where is your wisdom, pray? When a house is collapsing why should its master stay?’

- Pir Sultan Abdal (ca. 1480–1550) was a Turkish Alevi poet and ashik. During the time, Pir Sultan Abdal with the villagers, went against injustice, and was hanged by the Sivas governor Hızır pasha, who was once his comrade.[122] The opening quatrain of his composition, The Rough Man, is the following:[123]

Dostun en güzeli bahçesine bir hoyrat girmiş, --- (The rough man entered the lover's garden)

Korudur hey benli dilber korudur --- (It is woods now, my beautiful one, it is woods,)

Gülünü dererken dalını kırmış --- (Gathering roses, he has broken their stems)

Kurudur hey benli dilber kurudur --- (They are dry now, my beautiful one, they are dry)

- Hovasap Sebastasi (Armenian: Հովասափ Սեբաստացի; born about 1500, Sebastia - about 1564), 16th century Armenian gusan/ashug, verse teller, writer, testimonial writer. He stands out as one of the earliest known figures of Armenian vernacular lyric poetry in the post-medieval period, bridging the gap between classical Armenian literature and the emerging popular poetic tradition that would blossom in the works of Nahapet Kuchak and Sayat-Nova. A native of Sebastia (modern-day Sivas), then under Ottoman rule, Hovasap composed his poems in a language close to the spoken dialects of his time, incorporating folk elements, ethical reflection, and Christian spirituality. His writings were often moralistic in tone but emotionally rich, revealing the poet’s awareness of social decay, personal suffering, and the spiritual longing of his age. Hovasap’s works reflect a blend of homiletic storytelling and vernacular emotionality. Though few of his writings survive, his name appears in manuscripts from the 16th and 17th centuries, and his poems were transmitted orally or preserved by scribes in Armenian monastic centers. He is sometimes noted in Armenian literary encyclopedias as a “gusan of wisdom” — not only a performer, but a teacher through verse. While little biographical detail remains, it is believed that he traveled through villages near Sebastia, composing and performing for both clergy and common folk, and may have written testimonial chronicles about life under Ottoman rule. An example of one of the excerpts of his surviving poems:[124][125][126][127]

Աշնան առաջին ցուրտի տակ անցա ես պառավել,

Հիշողն ծառ թափել էր, սիրտս մառնել էր գարունին։

Under the autumn’s first frost I wandered and paused in sorrow,

Memory shed its leaves like trees, my heart mourned for spring’s tomorrow.

- Ashiq Qurbani was born in 1477 in Dirili. He was a contemporary of Shah Ismail and may have served as the court musician. His compositions were handed down as gems of oral art from generation to generation and constitute a necessary repertoire of every ashik. A famous qushma, titled Violet, starts as the following:[73][128]

Başina mən dönüm ala göz Pəri, --- (O my dearest, my love, my beautiful green-eyed Pari)

Adətdir dərələr yaz bənəvşəni. --- (Custom bids us pluck violets when spring days begin)

Ağ nazik əlinən dər dəstə bağla, --- (With your tender white hand gather a nosegay,)

Tər buxaq altinə düz bənəvşəni... --- (Pin it under your dainty chin.....)

15th-13th century

[edit]- Gusan Hovhannes Tlkurantsi (Armenian: Հովհաննես Թլկուանցի) was a prominent Armenian poet, hymnist, and representative of the late medieval gusan tradition. He lived approximately from the mid-15th to early 16th century (circa 1450–1535), a period marking the transition from classical Armenian literary traditions to the emerging ashugh culture. Tlkurantsi was born in the village of Tlkur, located in the historical region of Greater Armenia (likely near Western Armenia), from which he took his name. As one of the last known gusans, Tlkurantsi preserved the lyrical, moral, and spiritual dimensions of Armenian medieval verse while gradually incorporating elements of popular vernacular themes. His poetry reflects a unique synthesis of religious devotion, philosophical reflection, and lyrical beauty, with strong influences from Christian mysticism, biblical themes, and classical Armenian hymnography. He is best known for his sharakan-style hymns, religious odes, and lyrical poems centered around human weakness, divine love, and the fleeting nature of earthly life. Tlkurantsi wrote in Classical Armenian (Grabar), yet many of his works were widely read and sung, suggesting a connection to oral tradition. His writings served both as spiritual reflection and poetic art, and many of them were preserved in Armenian manuscript collections across monasteries in the Armenian Highlands and Cilicia. Though often overshadowed by later ashughs like Nahapet Kuchak or Sayat-Nova, Tlkurantsi holds a special place as a transitional figure, carrying forward the gusanic heritage while paving the way for the Armenian ashugh tradition of the 16th century and beyond. The following is an example of one of his poems:[129]

Անցեալ եմ երկինս տեսան,

Եւ արցունք իմ աչաց հոսան։

Անիծի այս աշխարհի փառք,

Որ մոլորեայ դարձուց ինձան։

I gazed upon the passing sky,

And tears poured freely from my eye.

Cursed be this world’s deceitful pride,

Which turned my soul from truth aside.

- Kaygusuz Abdal, was born in the late 14th century into a noble and aristocratic family of the Anatolian province of Teke and died in 1445. He traveled throughout the Middle East and eventually came to Cairo where he founded a Bektashi convent. Kaygusuz's poetry is among the strangest expressions of Sufism. He does not hesitate to describe in great detail his dreams of good food, nor does he shrink from singing about his love adventures with a charming young man. A tekerleme by Kaygusuz sounds like a nursery rhyme:[130]

kaplu kaplu bağalar kanatlanmiş uçmağa.. ---- The turturturtles have taken wings to fly ...

- Yunus Emre (1240–1321) was one of the first Turkish poets who wrote poems in his mother tongue rather than Persian or Arabic, which were the writing medium of the era. Emre was not literally an ashik, but his undeniable influence on the evolution of ashik literature is being felt to the present times.[90] The opening quatrain of his composition, Bülbül Kasidesi Sözleri, is as the following:[131]

İsmi sübhan virdin mi var? --- (is The Father's name your mantra?)

Bahçelerde yurdun mu var? --- (are those gardens your home?)

Bencileyin derdin mi var? --- (is your plight just as mine?)

Garip garip ötme bülbül --- (don't sing in sorrow nightingale)

- Frik (Armenian: Ֆրիկ) was an Armenian poet of the 13th and 14th centuries. While not an literal ashug or gusan, he wrote on both secular and religious topics, and many of his poems are characterized by social criticism. He was the first Armenian poet to compose almost all of his works in the vernacular language (Middle Armenian), making his voice especially accessible to the common people of his time and influencing future gusans and ashugs. Frik likely came from Western Armenia and was well-educated, possibly in a monastery. He eventually experienced a fall from grace, poverty, and captivity, and became a fierce critic of injustice, corruption, and hypocrisy. His poems question divine justice, mock the rich and the clergy, and lament the human condition. Despite not being a ashug/gusan by trade, his raw, direct style and concern for the people place him near the later ashugh tradition. A bit more than 50 of his poems survive. He likely died in the early 14th century. The following poem is one of his most popular:[132][133][134][128]

Աշխարհ, գի՛ր ի մտի քո խորամանկութիւն,

Չես թողի աշխարհիս սուրբ արդարութիւն։

Մեղաւոր ես միշտ, յաղթում ես հնձում,

Իսկ ճշմարտությունն՝ ի քո մոտ՝ ցած մնում։

O world, write down your treachery in your mind.

You never let truth or justice thrive.

The guilty you crown, you let them rise,

But truth you crush, and keep it low beneath lies.

Gusans before the 13th century

[edit]

Before the 13th century, there were no ashugs, but gusans (Armenian: գուսան) and before the gusans, vipasans (Armenian: վիպասան, lit. 'storytellers'). Vipasans were early oral narrators who recited epic tales and genealogies long before these stories were written down. Gusans followed as poet-musicians who combined music, poetry, and performance. They are mentioned in 5th-century ancient Armenian sources, like in the book History of Armenia by Movses Khorenatsi, who describes those who preserved national memory through spoken word.[135] Although the gusans were popular, only one is mentioned by name:

- Barbad (Persian: باربد; fl. late 6th – early 7th century CE) was a Persian musician-poet, music theorist and composer of Sasanian music, as well as a gusan.[137] In fact, he is the only gusan that is mentioned by name before the 15th century.[138] He served as chief minstrel-poet under the Shahanshah Khosrow II (r. 590–628). A barbat player, he was the most distinguished Persian musician of his time and is regarded among the major figures in the history of Persian music.[139]

See also

[edit]- Ashiqs of Azerbaijan

- Gusans

- Bard

- Minstrel

- Aqyn

- Bakshy

- Dengbêj

- Khananda

- Vardapet

- Ishq

- Daredevils of Sassoun

- Ashik Kerib and Ashiq Qarib

- Epic of Koroghlu

- Epic of Manas

- The Color of Pomegranates

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. 2013. ISBN 978-1136095948.

- ^ Russell, James R. (2018). "43. From Parthia to Robin Hood: The Epic of the Blind Man's Son". In DiTommaso, Lorenzo; Henze, Matthias; Adler, William (eds.). The Embroidered Bible: Studies in Biblical Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha in Honour of Michael E. Stone. Leiden: Brill. pp. 878–898. ISBN 9789004355880. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b Ziegler, Susanne (1997). "East Meets West - Urban Musical Styles in Georgia". In Stockmann, Doris; Koudal, Henrik Jens (eds.). Historical Studies on Folk and Traditional Music: ICTM Study Group on Historical Sources of Folk Music, Conference Report, Copenhagen, 24–28 April 1995. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 159–161. ISBN 8772894415.

- ^ a b Shidfar, Farhad (5 February 2019). "Azerbaijani Ashiq Saz in West and East Azerbaijan Provinces of Iran". In Özdemir, Ulas; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact Among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3956504815.

- ^ a b Yang, Xi (5 February 2019). "History and Organization of the Anatolian Ašuł/Âşık/Aşıq Bardic Traditions". In Özdemir, Ulas; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact Among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3956504815.

- ^ Kardaş, Canser (5 February 2019). "The Legacy of Sounds in Turkey: Âşıks and Dengbêjs". In Özdemir, Ulas; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact Among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3956504815.

- ^ Babayan, Kathryn; Pifer, Michael (7 May 2018). An Armenian Mediterranean: Words and Worlds in Motion. Springer. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-3319728650.

- ^ a b Colin P. Mitchell (Editor), New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society, 2011, Routledge, 90–92

- ^ Turpin, Andy (12 February 2010). "Nothing Sounds Armenian Like a Duduk: ALMA Lecture". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ On the origin of the word ešq

- ^ Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415366860.

- ^ Studies on the Soviet Union - 1971, Volume 11 - Page 71

- ^ Acharian, Hrachia (1971). "Gusan" գուսան. Hayerēn armatakan baṛaran Հայերէն արմատական բառարան [Armenian Etymological Dictionary] (in Armenian). Vol. 1 (Reprint of the 1926–1935 seven-volume ed.). Erevani hamalsarani hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 597–598.

- ^ Nigoghos G. Tahmizyan (2000). "Gusan Art in Historic Armenia". Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies. California State University: 101–106.

- ^ Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). The Heritage of Armenian Literature, Volume II: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 867–872. ISBN 0814330231.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (2002). "Gōsān". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XI/2: Golšani–Great Britain IV (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. pp. 167–170. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. 2013. pp. 851–852. ISBN 978-1136095948. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ century., Nahapet Kʻuchʻak, active 16th (1984). Come sit beside me and listen to Kouchag : Medieval Armenian poems of Nahabed Kouchag. Ashod Press. ISBN 0-935102-14-0. OCLC 10877190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). The Heritage of Armenian Literature, Volume II: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 867–872. ISBN 0814330231.

- ^ "Cathedral and Churches of Echmiatsin and the Archaeological Site of Zvartnots". World Heritage Convention. UNESCO. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). Hacikyan, Agop Jack (ed.). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century, Volume II. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 867–872. ISBN 0814330231. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Rouben Paul Adalian, Historical Dictionary of Armenia, 2010, p.452.

- ^ Charles Dowsett (1997). Sayatʻ-Nova: An 18th-century Troubadour : a Biographical and Literary Study. Peeters Publishers. pp. 70–73. ISBN 9789068317954.

- ^ Michnadar, by Agop Jack Hacikyan, Gabriel Basmajian, Edward S. Franchuk, Nourhan Ouzounian - 2002 - Page 1036

- ^ "Armenian ashugs". Encyclopedia Brittanica.

- ^ "Dastan Genre in Central Asia – Essays on Central Asia by H.B. Paksoy – Carrie Books". Vlib.iue.it. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ G. Lewis (translator), The Book of Dede Korkut, Penguin Classics(1988)

- ^ Köprülü, Mehmed Fuad (2006). Literary Influence. Early Mystics in Turkish Literature (PDF). pp. lii–lvi.

- ^ Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu (Editor), Culture and Learning in Islam, 2003, p. 282

- ^ "Atlas of traditional music of Azerbaijan". Atlas.musigi-dunya.az. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (1962). Türk Saz Şairleri I. Ankara: Güven Basımevi. p. 12.

- ^ Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415366860.

- ^ Today.az. Azerbaijan’s ashik art included into UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. 1 October 2009

- ^ Albright, C.F. "ʿĀŠEQ". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "ATLAS of Plucked Instruments – Middle East". ATLAS of Plucked Instruments. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ McCollum, Jonathan (2016). "Duduk (i)". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.L2294963.

- ^ Global Minstrels: Voices of World Music. Elijah Wald. 2012. p. 227. ISBN 9781135863685.

- ^ McCollum, Jonathan (2011). "Sring". Oxford Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.L2214963. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kipp, N. (2012). Organological geopolitics and the Balaban of Azerbaijan: comparative musical dialogues concerning a double-reed aerophone of the post-Soviet Caucasus (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign).

- ^ Turpin, Andy (12 February 2010). "Nothing Sounds Armenian Like a Duduk: ALMA Lecture". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Հայկական ժողովրդական խաղիկներ | Սիրո երգեր". Granish.org.

- ^ Ներսիսյան, Վարագ (2008). Հայ միջնադարյան տաղերգության ժանրերն ու տաղաչափությունը, (10-18դդ.) [Genres and meter of Armenian medieval poetry, (10-18th centuries)] (in Armenian). Երևան: Երևանի համալսարանի հրատարակչություն. pp. 11–26.

- ^ "Ashiq poems- Proverbs and sayings". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Poetry genres". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Der Hovanessian, Diana (1984). Come sit beside me and listen to Kouchag (1st ed.). New York, 1984: Ashod Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-935102-14-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Exploring Sayat Nova: Armenian ashug tradition". RS Global Journals.

- ^ "Sayat Nova: The Armenian Poet and Musician Who Shaped Caucasian Culture". Armenian History.

- ^ [1] Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Madatli, Eynulla (2010). Poetry of Azerbaijan (PDF). Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Islamabad. p. 110. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ A. Oldfield Senarslan, Women Aşiqs of Azerbaijan: Tradition and Transformation, 2008, ProQuest LLC., p. 44

- ^ Baṣgöz, I. (1967). Dream Motif in Turkish Folk Stories and Shamanistic Initiation. Asian Folklore Studies, 26(1), 1–18.

- ^ Basgoz, I. (1970). Turkish Hikaye-Telling Tradition in Azerbaijan, Iran. Journal of American Folklore, 83(330), 394.

- ^ Sabri Koz, M. "Comparative Bibliographic Notes on Karamanlidika Editions of Turkish Folk Stories" (PDF). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ^ "Performance of the Armenian epic of 'Daredevils of Sassoun' or 'David of Sassoun'". UNESCO. 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Performance of the Armenian epic of 'Daredevils of Sassoun' or 'David of Sassoun'". UNESCO. 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "UNESCO - Decision of the Intergovernmental Committee: 7.COM 11.2". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ "The Persianization of Koroglu : Banditry and Royalty in Three Versions of the Koroglu Destan" (PDF). Nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ^ "Legend of Akhtamar Island". Phoenix Tour.

- ^ Gallagher, Amelia (2009). "The Transformation of Shah Ismail Safevi in the Turkish Hikaye". Journal of Folklore Research. 46 (2): 173–196. doi:10.2979/jfr.2009.46.2.173. S2CID 161620767.

- ^ Petrosyan 2002, p. 79.

- ^ "The Legend of Ara the Beautiful". Arara.

- ^ James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov, 2013, Chap. 8

- ^ Moses Khorenatsʻi; Thomson, Robert W. (1978). "Genealogy of Greater Armenia". History of the Armenians. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-674-39571-9.

- ^ Katvalyan, M. (1980). "Hayk". In Hambardzumyan, Viktor (ed.). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 6. Yerevan. p. 166.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Petrosyan, Arsen (2018). The Armenian Epic and Mythology. Yerevan State University Press. p. 64.

- ^ Payaslian, Simon (2007). "The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present". Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ Azad Nabiyev, Azarbaycan xalq adabiyyati, 2006, Page 213

- ^ ÜSTÜNYER, Ýlyas (2009). "Tradition of the Ashugh Poetry and ashik in Georgia" (PDF). IBSU Scientific Journal. 3. 1: 137–149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ خبرگزاری باشگاه خبرنگاران | آخرین اخبار ایران و جهان | (26 October 1390). "مجموعه كتاب مكتب قوپوز در زمینه موسیقی عاشیقی منتشر شد". fa. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Ashugs through the centuries". Sayat Nova Cultural Union.

- ^ a b Oldfield Senarslan, Anna. "It's time to drink blood like its Sherbet": Azerbaijani women ashiqs and the transformation of tradition" (PDF). Congrès des musiques dans le monde de l'islam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ռ. Աթայան (1963). Գուսան Հավասի (կյանքը և ստեղծագործությունը). Երևան: Հայպետհրատ.

- ^ "Neşet Ertaş". Biyografi.net. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Untrue World". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Գուսան Շահեն". matyan.am. Retrieved 10 February 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "The memorial of Sargsyan Shahen (Շահեն Սարգսյան Եղիազարի) buried at Yerevan's Zeitun cemetery". hush.am. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Ashugh Hoseyn Javan". Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ (in Armenian) Aghababyan, S. «Չարենց, Եղիշե Աբգարի» (Charents, Yeghishe Abgari). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia. vol. viii. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1982, pp. 670-672.

- ^ Beledian, Krikor (2014). "Kara-Darvish and Armenian Futurism". International Yearbook of Futurism Studies. 4: 263–300. doi:10.1515/futur-2014-0025. ISBN 978-3-11-033400-5.

- ^ "Ozan Dünyasi" (PDF). 2012. pp. 17–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Ofelya Hambardzumyan: Queen of Armenian Song". Armenian Diaspora Museum. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "ՕՖԵԼՅԱ ՀԱՄԲԱՐՁՈՒՄՅԱՆ" [Ofelya Hambardzumyan]. AV Production. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Rasool, The prominent figure of Azeri music". Gunaz.tv. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "سازمان فرهنگی هنری – عاشيق رسول قرباني". Honar.tabriz.ir. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Ashik Rasool was awarded for achievements". Khabarfarsi.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "تولد 80 سالگی "عاشیق رسول" در فرهنگسرای نیاوران برگزار میشود". fa. 8 December 1392. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ a b Köprülü, Mehmed Fuad (2006). Literary Influence. Early Mystics in Turkish Literature (PDF). pp. 367–368. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Bouwgids.com". 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Aşık Mahzuni Şerif". Mahzuniserif.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Gulalys. "That's it, I go my black eyed". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ (in Russian) Хлеб духовный – «Армянский хлеб», 28-11-2011

- ^ "Black soil/earth". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Michnadar, by Agop Jack Hacikyan, Gabriel Basmajian, Edward S. Franchuk, Nourhan Ouzounian – 2002 – Page 1036

- ^ Stone Blackwell, Alice. "UNHAPPY DAYS". ArmenianHouse.org. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "K. Durgarian about Jivani". Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Naghiyeva, Shahla; Amirdabbaghian, Amin; Shunmugam, Krishnavanie (16 December 2019). "Ashik Basti: My Saz Wails for My Beloved". Southeast Asian Review of English. 56 (2): 116–138. doi:10.22452/sare.vol56no2.10.

- ^ Grigorian, Sh.; Manukian, M. (1982). "Sheram" Շերամ. In Arzumanian, Makich (ed.). Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran Հայկական սովետական հանրագիտարան [Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Vol. 8. Erevan: Haykakan hanragitarani glkhavor khmbagrutʻyun. pp. 484–485.

- ^ Davidjants, Brigitta (2015). "Identity construction in Armenian music on the example of early folklore movement". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore (62): 195. doi:10.7592/FEJF2015.62.davidjants.

- ^ Aşiq Ələsgər Əəsərləri (PDF). Bakı: ŞƏRQ-QƏRB. 2004. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Aşiq Ələsgər Gərayli LAR". Azeritest.com/. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Alim and Fargana Qasimov: Spiritual Music of Azerbaijan". Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Ով ով է. Հայեր. Կենսագրական հանրագիտարան, հատոր երկրորդ, Երևան, 2007.

- ^ Dowsett, Charles (1997), p. 4