Polish people

Polacy (Polish) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The flag of Poland, one of the symbols of Polish people | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 60 million[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States | 10,600,000 (2015)[1][3][4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 2,253,000 (2018)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brazil | 1,800,000 (2007)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canada | 1,010,705 (2013)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| France | 1,000,000 (2022)[8][9][10][11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 682,000 (2021)[12][13] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism[39] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other West Slavs Especially other Lechites | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Polish people, or Poles,[a] are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation[40][41][42] who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Central Europe. The preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland defines the Polish nation as comprising all the citizens of Poland, regardless of heritage or ethnicity. The majority of Poles adhere to Roman Catholicism.[39]

The population of self-declared Poles in Poland is estimated at 37,394,000 out of an overall population of 38,512,000 (based on the 2011 census),[43] of whom 36,522,000 declared Polish alone.[44][45][4] A wide-ranging Polish diaspora (the Polonia) exists throughout Eurasia, the Americas, and Australasia. Today, the largest urban concentrations of Poles are within the Warsaw metropolitan area and the Katowice urban area.

Ethnic Poles are considered to be the descendants of the ancient West Slavic Lechites and other tribes that inhabited the Polish territories during the late antiquity period. Poland's recorded history dates back over a thousand years to c. 930–960 AD, when the Western Polans – an influential tribe in the Greater Poland region – united various Lechitic clans under what became the Piast dynasty,[46] thus creating the first Polish state. The subsequent Christianization of Poland by the Catholic Church, in 966 CE, marked Poland's advent to the community of Western Christendom. However, throughout its existence, the Polish state followed a tolerant policy towards minorities resulting in numerous ethnic and religious identities of the Poles, such as Polish Jews.

Exonyms

The Polish endonym Polacy is derived from the Western Polans, a Lechitic tribe which inhabited lands around the River Warta in Greater Poland region from the mid-6th century onward.[47] The tribe's name stems from the Proto-Indo European *pleh₂-, which means flat or flatland and corresponds to the topography of a region that the Western Polans initially settled.[48][49] The prefix pol- is used in most world languages when referring to Poles (Spanish polaco, Italian polacche, French polonais, German Pole).

Among other foreign exonyms for the Polish people are Lithuanian Lenkai; Hungarian Lengyelek; Turkish Leh; Armenian: Լեհաստան Lehastan; and Persian: لهستان (Lahestān). These stem from Lechia, the ancient name for Poland, or from the tribal Lendians. Their names are equally derived from the Old Polish term lęda, meaning plain or field.[50]

Ethnogenesis

The Polish people are descended from a blend of various ancient ethnic groups that inhabited the territory of modern-day Poland before and during late antiquity.[51][52] The area was settled by numerous tribes and cultures, including Baltic, Celtic, Germanic, Slavic, Thracian, and possibly remnants of earlier Proto-Indo-Europeans and non-Indo-European peoples.[51] Archaeological evidence from the Lusatian culture (c. 1300–500 BCE), as well as the successive Pomeranian, Przeworsk and Wielbark cultures, points to a diverse demographic landscape in prehistoric Poland.[51] These cultures were associated with different ethnic groups, such as the Celts (notably in southern Poland), Germanic tribes like the Vandals and Goths, and the Balts in the northeast.[51][53]

During the Migration Period, the region was becoming increasingly settled by the early Slavs (c. 500–700 AD).[54] The Slavic settlers organised into tribal units and assimilated the remnants of earlier populations, thus contributing to the West Slavic ethnogenesis and identity of the numerous Polish tribes and Lechites.[55][56] The names of many tribes are found on the list compiled by the anonymous Bavarian Geographer in the 9th century.[57] In the 9th and 10th centuries the tribes gave rise to developed regions along the upper Vistula (the Vistulans),[57] the Baltic Sea coast and in Greater Poland. The ultimate tribal undertaking (10th century) resulted in a lasting political structure and the creation of a Polish state.[58][59]

Language

Polish is the native language of most Poles. It is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group and the sole official language in the Republic of Poland. Its written form uses the Polish alphabet, which is the basic Latin alphabet with the addition of six diacritic marks, totalling 32 letters. Bearing relation to Czech and Slovak, it has been profoundly influenced by Latin, German and other languages over the course of history.[60][61] Poland is linguistically homogeneous – nearly 97% of Poland's citizens declare Polish as their mother tongue.[62]

Polish-speakers use the language in a uniform manner throughout most of Poland, though numerous dialects and a vernacular language in certain regions coexist alongside standard Polish. The most common lects in Poland are Silesian, spoken in Upper Silesia, and Kashubian, widely spoken in historic Eastern Pomerania (Pomerelia), today in the northwestern part of Poland.[63] Kashubian possesses its own status as a separate language.[64][65] The Goral people in the mountainous south use their own nonstandard dialect, accenting and different intonation.

The geographical distribution of the Polish language was greatly affected by the border changes and population transfers that followed the Second World War – forced expulsions and resettlement during that period contributed to the country's current linguistic homogeneity.[66]

History synopsis

Protohistoric

During the Neolithic period (c. 5500–2300 BCE), farming communities began to spread across the contemporary Polish lands, introducing agriculture, pottery, and domesticated animals.[67] The Lengyel, Funnelbeaker, and Globular Amphora cultures were notable for their megalithic tombs, settlements, and ceramics.[68][69][70] The Bronze Age (c. 2300–700 BCE) precipitated considerable advancements in craftsmanship with the emergence of the Unetice culture and later the Lusatian culture, the latter of which built the fortified settlement at Biskupin in the 8th century BC.[71][72] These communities engaged in bronze metallurgy, long-distance trade, and complex burial rites, including urnfield cremation cemeteries.[72] Among some of the significant archaeological or megalithic sites in Poland are Bodzia (cemetery), Borkowo (cemetery), Nowa Cerekwia (excavations), Odry (stone circles), Węsiory (stone circles), and Wietrzychowice (mounds).

Classical

Poland's history during classical antiquity is primarily reconstructed through archaeological evidence, as the region lay outside the Roman Empire and produced few written records.[73] In the 1st century BCE, the area was inhabited by Celtic tribes, notably the Boii, who established settlements in Lower Silesia.[73] These groups were part of the La Tène culture, recognised for advanced metallurgy, intricate ornamentation, and distinctive burial customs.[73] Evidence from sites along the Amber Road, a major trade route linking the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean, indicates Poland's role as a corridor for goods like amber and ceramics during this period.[73]

In the early centuries CE, the Przeworsk culture flourished in central and southern Poland, succeeding Celtic presence.[74] The Przeworsk culture is notable for its cremation burials, iron weaponry, and Roman imports.[74] Roman coins and military artifacts discovered in the Kuyavia region suggest contact between local populations and the Roman Empire, possibly through trade or mercenary service.[74] By the 2nd century CE, the Wielbark culture, linked to Germanic peoples, began to dominate northern and central Poland and gradually replaced the earlier Oksywie culture.[75] The Wielbark people did not bury weapons in graves, a practice distinct from their Przeworsk neighbours, but their cemeteries reveal long-distance contacts through Roman goods, including Roman glassware.[76] The eventual decline of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries coincided with the southward relocation of the Goths, leaving behind a cultural vacuum that was gradually filled by Slavic migration.[77] The incoming tribes built defensive settlements called gords across much of Poland.[78]

Medieval

The medieval history of Poland began in the 10th century with the rise of the Piast dynasty.[79] Under Mieszko I, who accepted Christianity in 966 AD, Poland entered the sphere of Western Latin Christendom.[80] This baptism marked the beginning of statehood and allowed the formation of diplomatic ties with the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy.[80] His son, Bolesław I the Brave, expanded the kingdom and was crowned the first King of Poland in 1025, establishing Poland as a regional power.[81] However, his successors struggled to maintain control, and the country faced internal unrest, succession disputes, and pagan uprisings that weakened central authority.[82]

In 1079, Bolesław II the Bold entered a conflict with the Catholic Church, culminating in the execution of Bishop Stanislaus, which led to his downfall and exile.[83] After the death of Bolesław III Wrymouth in 1138, Poland entered a period of fragmentation, as the kingdom was divided among his sons into regional duchies.[84] This weakened central authority and made the country vulnerable to external threats, including devastating Mongol invasions in the 13th century.[85][86] However, the era also saw the growth of towns under Magdeburg Law, the settlement of foreign populations, and the founding of many institutions.[87][88] The Teutonic Order, invited to confront pagan Old Prussians by Konrad I of Masovia, established its own state in the northeastern Baltic region, eventually becoming a hostile neighbour.[89]

Poland’s reunification began under Władysław I the Elbow-high,[90] who was crowned at Wawel Cathedral in 1320, and continued under his son, Casimir III the Great, who strengthened royal authority, modernised the legal system, and promoted education by founding the first Polish university in 1364.[91] In 1385, the Union of Krewo united the Kingdom of Poland (Jadwiga) and the neighbouring Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Jogaila) under the Jagiellonian dynasty, forming a powerful Christian alliance in East-Central Europe.[92] The Battle of Grunwald in 1410 marked a turning point in the struggle against the Teutonic State.[92] By the late Middle Ages, Poland had emerged as a major European kingdom with growing political, cultural, and military influence.[92]

Early modern

Between 1500 and the early 17th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth emerged as one of the most powerful and expansive states in Europe.[93] Established through the Union of Lublin in 1569, it united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania under a single elected monarch and a shared parliament (Sejm).[93] Governed by a unique system of noble democracy (Golden Liberty), the Commonwealth was characterised by a politically active nobility (szlachta) who wielded considerable political influence.[93] This period is often regarded as Poland’s Golden Age, marked by territorial expansion and Polonisation, but also by religious tolerance enshrined in the Warsaw Confederation of 1573, and a flourishing of intellectual and cultural life.[94][95] However, the death of Sigismund II Augustus in 1572 ushered in an era of instability driven by the weaknesses of an elective monarchy.[96] The Vasa dynasty ruled from 1587 to 1668, beginning with Sigismund III, who also claimed the Swedish throne and moved Poland's capital from Kraków to Warsaw in 1596.[97]

The mid-17th century marked the beginning of a prolonged period of decline for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[98] A series of destructive conflicts severely weakened the state and destabilised its frontiers, notably Ukraine's struggle for independence from Poland during the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648) and the Swedish Deluge (1655–1660).[98] Simultaneous wars with the Ottoman Empire and Russia further strained the Commonwealth’s resources and exposed its military and administrative vulnerabilities.[98] Internally, governance was crippled by the liberum veto, a parliamentary mechanism that allowed any deputy to block legislation and dissolve the Sejm, rendering meaningful reform nearly impossible.[99] Although symbolic military successes occurred, most notably John III Sobieski’s decisive role in the Battle of Vienna (1683), the victories could not compensate for the growing structural dysfunction.[100]

In the 18th century, the situation deteriorated further.[101] The Saxon kings from the House of Wettin, who ruled Poland in personal union, presided over a period of deepening political stagnation and increasing foreign interference.[101] Despite reformist efforts by Stanislaus II Augustus, culminating in the progressive Constitution of May 3, 1791 aimed to strengthen central authority and modernise the state, these initiatives were met with hostility from neighbouring powers.[102] In response, Russia, Prussia, and Austria orchestrated a series of territorial partitions in 1772, 1793, and 1795, thus erasing the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from the map.[103] By the close of the 18th century, Poland had ceased to exist as a sovereign state, initiating a long period of interchanging foreign rule that would last until the early 20th century.

Contemporary

After 123 years of partition, Poland regained independence in 1918 at the end of World War I, forming the Second Polish Republic under the leadership of Józef Piłsudski.[104] The interwar period (1918–1939) was marked by efforts to consolidate borders, build a modern state, and manage deep political divisions.[105][106] In 1939, Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany from the west and the Soviet Union from the east, triggering World War II.[107] The country was occupied, but maintained its sovereignty through the establishment of the Polish Government-in-Exile, initially based in France and later in London.[108] This government coordinated resistance efforts at home through the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), one of the largest underground movements in German-occupied Europe.[108] Despite this, Poland suffered immense human and material losses, including the deaths of around six million Polish citizens, half of them Polish Jews who perished in various Nazi concentration and extermination camps during the Holocaust.[108]

After the war, Poland fell within the Soviet sphere of political influence and became a communist country, the Polish People's Republic, under a one-party regime headed by the Polish United Workers' Party.[109] The postwar period was marked by centralised planning, nationalisation of industry, and political repression, including censorship and the suppression of dissents.[110] Despite periods of relative stability, widespread dissatisfaction with economic hardship and lack of political freedom persisted.[110] This discontent culminated in the emergence of the Solidarity (Solidarność) movement in the early 1980s, led by Lech Wałęsa, which began as an independent trade union and evolved into a broader social and political force.[110] Following the end of martial law (1981–1983), facing economic crisis and mounting internal pressure, the communist government entered negotiations with opposition leaders, leading to the Round Table Talks and the 1989 Polish parliamentary election.[110][111] These events marked the beginning of a peaceful transition to democracy and to the establishment of the contemporary Third Polish Republic.[111]

Since 1989, Poland has undergone significant political, economic, and social transformation. The country transitioned from a centrally planned economy to a market-based system and joined NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004.[112] Poland remains a key player in Central Europe, with a growing economy, strong civil society, and a significant role in supporting regional security.

Culture

The culture of Poland is closely connected with its intricate 1,000-year history, and forms an important constituent in the Western civilisation.[113] Strong ties with the Latinate world and the Roman Catholic faith also shaped Poland's cultural identity.[114][115] Various regions in Poland such as Greater Poland, Lesser Poland, Kuyavia, Masovia, Silesia, and Pomerania developed their own distinct cultures, cuisines, folklore and dialects. Also, Poland for centuries was a refuge to countless ethnic and religious minorities, who became an important part of Polish society and similarly developed their own unique customs.[116]

Symbols

The Constitution of Poland from 1997 defines official state symbols of the Third Polish Republic as: the crowned white-tailed eagle (bielik, orzeł biały) embedded on the coat of arms of Poland (godło),[117] the white and red flag of Poland (flaga), and the national anthem.[117] The national colours along with variants of the white eagle often feature on banners, cockades, pins, and memorabilia. Among other unofficial and more nature-based symbols is the white stork (bocian), the European bison (żubr), the red poppy flower (mak), the oak tree (dąb), and the apple (jabłko) as the country's national fruit.[118][119] Polonia has been the national personification and embodiment of Poland; it represents an allegorical female figure that personifies the Polish nation, much like Britannia for Great Britain or Marianne for France.[118]

Names and speech etiquette

In Poland, naming conventions are governed by well-defined linguistic and cultural norms.[120] Polish naming laws set by the Polish Language Council strictly ensure consistency with linguistic rules.[120] A full name typically comprises one or two given names followed by a surname. Given names, of various linguistic origins, are often associated with name days (imieniny) that were once widely celebrated.[121] Surnames are generally inherited and reflect grammatical gender; for instance, the masculine form Kowalski corresponds to the feminine Kowalska.[122] Some surnames, such as Nowak, remain unchanged regardless of gender. Plural forms are also used when referring to families, such as Kowalscy.[122]

Many surnames derive from occupational titles, geographic locations, or descriptive traits.[122] Since the High Middle Ages, Polish-sounding surnames ending with the masculine -ski suffix and the corresponding feminine suffix -ska were associated with the nobility.[123] Nobles also utilised Roman naming conventions, including agnomens. In speech etiquette, the Polish language maintains strict T–V distinction pronouns, honorifics and formalities when addressing individuals in vocative case (Pan for an adult man, Pani for an adult woman, Panna for a young unmarried woman); the extent to which affectionate forms or name diminutives are used can vary.[124]

Literature

According to a 2020 study, Poland ranks 12th globally on a list of countries which read the most, and approximately 79% of Poles read the news more than once a day, placing it second behind Sweden.[125] As of 2021, six Poles received the Nobel Prize in Literature.[b] The national epic is Pan Tadeusz (English: Master Thaddeus), written by Adam Mickiewicz. Renowned novelists who gained much recognition abroad include Joseph Conrad (wrote in English; Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim), Stanisław Lem (science-fiction; Solaris) and Andrzej Sapkowski (fantasy; The Witcher).

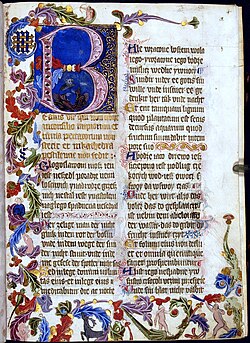

Earliest examples of Polish literature date back to the 10th and 11th centuries, when they were primarily written in Latin, with religious texts and chronicles like Gesta principum Polonorum by Gallus Anonymus (early 12th century) providing a foundational account of Poland's early rulers.[126] The Holy Cross Sermons are the oldest extant prose texts in Polish, dating from the 14th century and preserved only in fragments.[127] Saint Florian's Psalter, a trilingual manuscript in Latin, Polish, and German, is one of the earliest complete translations of the Psalms, and the Bible of Queen Sophia is the first complete translation of the Bible into Polish.[127] This period of Latin-dominated writing gradually gave way to the use of the Polish language in literature during the Renaissance (Mikołaj Rey and Jan Kochanowski) in the 16th century.[128]

Education and sciences

Personal achievement and education plays an important role in Polish society today. In 2018, the Programme for International Student Assessment ranked Poland 11th in the world for mathematics, science and reading.[129] Education has been of prime interest to Poland since the early 12th century, particularly for its noble classes. In 1364, King Casimir the Great founded the Kraków Academy, which would become Jagiellonian University, the second-oldest institution of higher learning in Central Europe.[130]

Poland made important contributions to science, particularly during the Renaissance and Enlightenment; among the chief figures was Nicolaus Copernicus, who revolutionised astronomy with his heliocentric theory. During the partitions in the 18th and 19th centuries, scientific societies and educational efforts kept knowledge alive.[131] The Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning, Kraków's Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences and secret teaching networks (Flying University) played crucial roles in preserving intellectual life.[131] In the 20th century, Poland produced several Nobel Prize winners in science, including Marie Skłodowska–Curie, a pioneer in radioactivity. People of Polish birth or citizenship have also made considerable contributions in the fields of philosophy, psychology, technology and mathematics both in Poland and abroad,[132] among them Alfred Tarski, Benoit Mandelbrot, Bronisław Malinowski, Leonid Hurwicz, Leszek Kołakowski, Ralph Modjeski, Rudolf Weigl, Solomon Asch, Stefan Banach, and Stanisław Ulam.

Music and dance

Traditional Polish music is characterised by distinctive regional styles and features folk instruments such as the fiddle, accordion, and clarinet.[133] Particularly notable is the highland bagpipe and fiddle music from the Tatra Mountains, recognised for its dynamic rhythms and expressive melodies. Poland has also made significant contributions to the classical music canon, most prominently through the works of Polish pianist and composer Frédéric Chopin, whose compositions remain central to the Romantic repertoire.

The Polish folk dances, including the polonaise, mazurka, krakowiak (cracovienne), oberek, and kujawiak, feature diverse rhythmic structures, tempos and choreographic patterns.[133] Moreover, the polka resonated with Polish dance traditions and was incorporated into local repertoires.[134] The dance tunes were popularised by Chopin in Europe and by the Polish-American community in North America.[135][134]

Latin songs and religious hymns such as Gaude Mater Polonia and Bogurodzica were once chanted in places of worship and during festivities, but the tradition has faded.[136] Sung poetry, disco polo and jazz remain important in Poland’s musical identity, the latter supported by a strong tradition dating back to the mid-20th century.[137] In modern times, hip-hop has emerged as one of the most influential genres among younger audiences, often characterised by its strong connection to urban culture.[137]

Art

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Poland absorbed Western European artistic influences while developing its own unique expressions.[138] Gothic architecture, in particular Brick Gothic, as well as religious iconography, and illuminated manuscripts flourished in the medieval period, followed by a Renaissance golden age in music and architecture influenced by Italy and the Netherlands.[138][139] Artists like Jan Matejko in the 19th century brought national history to life with historical painting, which played a significant role in fostering Polish identity.[138] In the 20th and 21st centuries, Polish art reflected the country’s shifting political and cultural landscape; the various styles comprised Modernism, Art Deco, Surrealism, Socialist Realism and Abstract art. In general, Polish art is deeply engaged with questions of history, identity, and resilience.[140]

The use of colourful flower motifs, woodworking, papercutting, and needlework are important parts of Polish folk art.[141] Traditional Polish folk costumes (stroje ludowe) often feature rich embroidery, vivid colours, and decorative elements such as beads, ribbons, and lace.[142] Women’s attire typically includes long skirts, aprons, embroidered blouses, corsets or vests, and headscarves or wreaths,[142] while men’s outfits often feature embroidered shirts, sashes, hats, and high boots.[143] Some of the most well-known regional costumes include the Łowicz garb, the Goral (Highlander) clothing from the Tatra Mountains, and the Kraków costume, often considered Poland's national dress.[143] Rogatywka, also known as a "konfederatka", is a type of hat which originated in Poland and is worn by the military.

Food culture

Meals are typically structured around three main parts: breakfast (śniadanie), dinner (obiad), the largest meal of the day, and supper (kolacja), though eating second breakfast (drugie śniadanie) or evening snacks is characteristic for Poland.[144] Popular everyday foods include pork cutlets (kotlet schabowy), schnitzels, kielbasa sausage, potatoes, coleslaw and salads, soups (barszcz, tomato or meat broth), pierogi dumplings, and various types of bread (kaiser rolls, rye bread, bagels). Polish cuisine also reflects strong seasonal and religious influences; during Lent, traditional dishes become meatless, often featuring fish like herring or carp, while Christmas Eve (Wigilia) is celebrated with a twelve-dish vegetarian meal.[145]

Traditional Polish cuisine is hearty and Poles are one of the more obese nations in Europe – approximately 58% of the adult population was overweight in 2019, above the EU average.[146] According to data from 2017, meat consumption per capita in Poland was one of the highest in the world, with pork being the most in demand.[147] Vegetarianism is on the rise, though this is not measured by the Statistical Office. Alcohol consumption is relatively moderate compared to other European states;[148] popular alcoholic beverages include Polish-produced beer, vodka and ciders.

Religion

Poles have traditionally adhered to the Christian faith; an overwhelming majority belongs to the Roman Catholic Church,[149] with 87.5% of Poles in 2011 identifying as Roman Catholic.[150] According to Poland's Constitution, freedom of religion is ensured to everyone. It also allows for national and ethnic minorities to have the right to establish educational and cultural institutions, institutions designed to protect religious identity, as well as to participate in the resolution of matters connected with their cultural identity.

There are smaller communities primarily comprising Protestants (especially Lutherans), Orthodox Christians (migrants), Jehovah's Witnesses, those irreligious, and Judaism (mostly from the Jewish populations in Poland who have lived in Poland prior to World War II)[151] and Sunni Muslims (Polish Tatars). Roman Catholics live all over the country, while Orthodox Christians can be found mostly in the far north-eastern corner, in the area of Białystok, and Protestants in Cieszyn Silesia and Warmia-Masuria regions. A growing Jewish population exists in major cities, especially in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław. Over two million Jews of Polish origin reside in the United States, Brazil, and Israel.[citation needed]

Religious organisations in the Republic of Poland can register their institution with the Ministry of Interior and Administration creating a record of churches and other religious organisations who operate under separate Polish laws. This registration is not necessary; however, it is beneficial when it comes to serving the freedom of religious practice laws.[citation needed]

Slavic Native Faith (Rodzimowiercy) groups, registered with the Polish authorities in 1995, are the Native Polish Church (Rodzimy Kościół Polski), which represents a pagan tradition going back to Władysław Kołodziej's 1921 Holy Circle of Worshippers of Światowid (Święte Koło Czcicieli Światowida), and the Polish Slavic Church (Polski Kościół Słowiański). There is also the Native Faith Association (Zrzeszenie Rodzimej Wiary, ZRW), founded in 1996.[152]

Geographic distribution

Polish people are the fifth-largest national group in the European Union (EU) after Germans, French, Italians and Spaniards.[153] Estimates vary depending on source, though available data suggest a total number of up to 60 million people worldwide (with up to 22 million living outside of Poland).[1] There are almost 38 million Poles in Poland alone.[154] There are also strong Polish communities in neighbouring countries, whose territories were once occupied or part of Poland – western Belarus, western Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia and in the Cieszyn Silesia region of the Czech Republic.[1]

The term "Polonia" is usually used in Poland to refer to people of Polish origin who live outside Polish borders. There is a notable Polish diaspora in the United States, Brazil, and Canada. France has a historic relationship with Poland and has a relatively large Polish-descendant population. Poles have lived in France since the 18th century. In the early 20th century, over a million Polish people settled in France, mostly during world wars, among them Polish émigrés fleeing either Nazi occupation (1939–1945) or Communism (1945/1947–1989). There is also a notable Polish diaspora in the United Kingdom and in Germany.[1]

In the United States, a significant number of Polish immigrants settled in Chicago (billed as the world's most Polish city outside of Poland), Milwaukee, Ohio, Detroit, New Jersey, New York City, Orlando, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and New England. The highest concentration of Polish Americans in a single New England municipality is in New Britain, Connecticut. In year 1900 the largest Catholic Polish communities in the United States were in Pennsylvania, New York State, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan.[155] The majority of Polish Canadians have arrived in Canada since World War II. The number of Polish immigrants increased between 1945 and 1970, and again after the end of Communism in Poland in 1989. In Brazil, the majority of Polish immigrants settled in Paraná State. Smaller, but significant numbers settled in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Espírito Santo and São Paulo (state). The city of Curitiba has the second largest Polish diaspora in the world (after Chicago) and Polish music, dishes and culture are quite common in the region.

A recent large migration of Poles took place following Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004 and with the opening of the EU's labor market; an approximate number of 2 million, primarily young, Poles taking up jobs abroad.[156] It is estimated that over half a million Polish people went to work in the United Kingdom from Poland. Since 2011, Poles have been able to work freely throughout the EU where they have had full working rights since Poland's EU accession in 2004. The Polish community in Norway has increased substantially and has grown to a total number of 120,000, making Poles the largest immigrant group in Norway. Only in recent years has the population abroad decreased, specifically in the UK with 116.000 leaving the UK in 2018 alone. There is a large minority of Polish people in Ireland that makes up approximately 2.57% of the population.[157]

See also

- Demographics of Poland

- Karta Polaka

- Lechites

- List of Poles

- Names of Poland (etymology of the demonym)

- Pole and Hungarian brothers be

- Poles in France

- Poles in Germany

- Poles in Latvia

- Poles in Lithuania

- Poles in Norway

- Poles in Romania

- Poles in the Soviet Union

- Poles in Spain

- Poles in the United Kingdom

- Polish Americans

- Polish Argentines

- Polish Australians

- Polish Brazilians

- Polish Canadians

- Polish Chileans

- Polish Mexicans

- Polish minority in Ireland

- Polish Czechs

- Polish nationality law

- Polish New Zealanders

- Polish Uruguayans

- Polish Venezuelans

- Polonisation

- Sons of Poland

- West Slavs

Notes

- ^ Polish: Polacy, pronounced [pɔˈlat͡sɨ]; singular masculine: Polak, singular feminine: Polka

- ^ In some instances only five laureates are acknowledged as Isaac Bashevis Singer resided in the United States and primarily wrote in Yiddish.

References

- ^ a b c d e 37.5–38 million in Poland and 21–22 million ethnic Poles or people of ethnic Polish extraction elsewhere. "Polmap. Rozmieszczenie ludności pochodzenia polskiego (w mln)" Archived 30 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ GUS. "Tablice z ostatecznymi danymi w zakresie przynależności narodowo-etnicznej, języka używanego w domu oraz przynależności do wyznania religijnego". stat.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Wspolnota-polska.org.pl. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ a b Główny Urząd Statystyczny (January 2013). Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna [Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011] (PDF) (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny. pp. 89–101. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus - Fachserie 1 Reihe 2.2 - 2018 Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, page 62, retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Polska Diaspora na świecie, Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska, 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Erwin Dopf. "Présentation de la Pologne". diplomatie.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Présentation de la Pologne". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Europe: where do people live?". Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Polonia w liczbach". Stowarzyszenie "Wspólnota Polska". Archived from the original on 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Population of the United Kingdom by country of birth and nationality, July 2020 to June 2021". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2023..

- ^ "Polish workers abandon brexit Britain in favour of Germany:Aljazeera.com". Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Clarín.com – La ampliación de la Unión Europea habilita a 600 mil argentinos para ser comunitarios". Edant.clarin.com. 27 April 2004. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government". Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Jews, by Country of Origin and Age". Statistical Abstract of Israel (in English and Hebrew). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "2021 censusm". 16 December 2015. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian Census 2001". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Polacy przestali kochać Irlandię. Myślą o powrocie". 17 October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents". 9 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ "Maleje liczba Polaków we Włoszech" [The number of Poles in Italy is decreasing]. Naszswiat.net (in Polish). Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Befolkning efter födelseland och ursprungsland 31 december 2012" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 31 December 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft//bevoelkerung_am_1.1.2015_nach_detailliertem_geburtsland_und_bundesland-2.pdf [dead link]

- ^ a b c "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". 10 February 2014. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ a b Wspólnota Polska. "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Wspolnota-polska.org.pl. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "On key provisional results of Population and Housing Census 2011". Csb.gov.lv. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Statistics Denmark:FOLK1: Population at the first day of the quarter by sex, age, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship". Statistics Denmark. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Kazakhstan National Census 2009". Stat.kz. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018.

- ^ Wspólnota Polska. "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Wspolnota-polska.org.pl. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Population by country of birth, sex and age 1 January 1998-2022". Statistics Iceland. 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Foreigners by category of residence, sex, and citizenship as at 31 December 2016". Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Ante la crisis, Europa y el mundo miran a Latinoamérica". Acercando Naciones (in Spanish). 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^ "SODB2021 - Obyvatelia - Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Sefstat2022" (PDF).

- ^ "在留外国人統計" (in Japanese). 15 December 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Niektóre wyznania religijne w Polsce w 2017 r. (Selected religious denominations in Poland in 2017)" (PDF). Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2018 (Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland 2018) (in Polish and English). Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2018. pp. 114–115. ISSN 1640-3630. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Historya ksia̜ża̜t i królów polskich krótko zebrana – Teodor Waga – Google Books. J. Zawadzki. 9 July 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Historya krolow i ksiazat polskich krotko zebrana dla lepszego uzytku Wyd ... – Theodor Waga – Google Books. Zupanski. 9 July 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Gerard Labuda. Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny zachodniej, t. 1–2 s.72 2002; Henryk Łowmiański. Początki Polski: z dziejów Słowian w I tysiącleciu n.e., t. 5 s.472; Stanisław Henryk Badeni, 1923. s. 270.

- ^ Central Statistical Office (January 2013). "The national-ethnic affiliation in the population – The results of the census of population and housing in 2011" (PDF) (in Polish). p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Gudaszewski, Grzegorz (November 2015). Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski. Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 (PDF). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. pp. 132–136. ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski [Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011] (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. November 2015. pp. 129–136. ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Gerard Labuda. Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny zachodniej, t.1–2 p.72 2002; Henryk Łowmiański. Początki Polski: z dziejów Słowian w I tysiącleciu n.e., t. 5 p.472; Stanisław Henryk Badeni, 1923. p. 270.

- ^ Gliński, Mikołaj (6 December 2016). "The Many Different Names of Poland". Culture.pl. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz (1978). Język polski. Pochodzenie, powstanie, rozwój. Warszawa (Warsaw): Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 64.

- ^ Potkański, Karol (2004) [1922]. Pisma pośmiertne. Granice plemienia Polan. Vol. 1 & 2. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 423. ISBN 978-83-7063-411-7. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Małecki, Antoni (1907). Lechici w świetle historycznej krytyki. Lwów: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 37. ISBN 978-83-65746-64-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b c d Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–60. ISBN 9780199752720. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Łukowski, Jerzy; Zawadzki, Hubert (2020). "1: Piast Poland". A concise history of Poland. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 9781108424363.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1971). The Slavs. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 21–45. ISBN 9780500020722.

- ^ Zbigniew Kobyliński. "The Slavs" Archived 22 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine. The New Cambridge Medieval History, pp. 530–537

- ^ Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs. History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c.500–700. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 1–35. ISBN 9780511017797. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Zenon Klemensiewicz: Historia języka polskiego t.III. Warszawa: PWN, 1985. P. 418-471. ISBN 83-01-06443-9.

- ^ a b Norman Davies (2005). God's Playground A History of Poland: Volume 1: The Origins to 1795: Origins. OUP Oxford. p. xxvii. ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5.

- ^ Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs. History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c.500–700. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 298–320. ISBN 9780511017797. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Marek Derwich; Adam Żurek (2002). U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038) (in Polish). pp. 122–143.

- ^ "Język polski". Towarzystwo Miłośników Języka Polskiego. 27 July 2000. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mańczak-Wohlfeld, Elżbieta (27 July 1995). Tendencje rozwojowe współczesnych zapożyczeń angielskich w języku polskim. Universitas. ISBN 978-83-7052-347-3. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Which Languages Are Spoken in Poland?". WorldAtlas. 18 July 2018. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Lucjan Adamczuk; Sławomir Łodziński (2006). Mniejszości narodowe w Polsce w świetle Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego z 2002 roku. Warszawa (Warsaw): Wydawn. Nauk. Scholar. p. 149. ISBN 978-83-7383-143-8.

- ^ "Acta Cassubiana. Vol. XVII (map on p. 122)". Instytut Kaszubski. 2015. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Kaschuben heute: Kultur-Sprache-Identität" (PDF) (in German). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Janowska, Iwona; Gębal, Przemysław (2024). Theory and Practice of Polish Language Teaching. V&R Unipress. p. 127. ISBN 9783847016502. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

- ^ Fibiger, Linda; Schulting, Rick J. (2012). Sticks, stones, and broken bones : neolithic violence in a European perspective. Oxford: University Press. pp. 52–54. ISBN 9780199573066. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Darvill, Timothy (2021). Lengyel Culture. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 9780191842788.

- ^ Florek, Marek (2020). "Megalithic Cemeteries of the Funnel Beaker Culture in the Sandomierz Upland". Sprawozdania Archeologiczne. 72 (1): 213–232. doi:10.23858/SA/72.2020.1.010. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Nogaj-Chachaj, Jolanta (2019). "The Funnel Beaker Culture in the Lublin Region in the Light of the Excavations and Publications of Jan Kowalczyk". Archeologia Polona. 57: 145–156. doi:10.23858/APa57.2019.010. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2015). People of the Earth. An Introduction to World Prehistory. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781317346814. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Colin Haselgrove, Katharina Rebay-Salisbury, Peter S. Wells (2023). The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age. Oxford: University Press. pp. 194–196. ISBN 9780191019470. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Dzięgielewski, Karol (2016). Societies of the younger segment of the early Iron Age in Poland (500-250 BC). Warszawa (Warsaw): Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences. pp. 42–45. ISBN 9788363760915. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Olędzki, Marek (2004). "The Wielbark and Przeworsk Cultures at the Turn of the Early and Late Roman Periods". The Dynamics of Settlement and Cultural Changes in the Light of Chronology: 17–20. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Cieśliński, Adam (2016). "The society of Wielbark culture, AD 1‒300". The Past Societies. Polish Lands from the First Evidence of Human Presence to the Early Middle Ages. 4. Warszawa (Warsaw): 217–255. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Kontny, Bartosz (2023). Archaeology of War: Studies on Weapons of Barbarian Europe in the Roman and Migration Period. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 75–117. ISBN 9782503607375. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Urbańczyk, Przemysław (2008). Franks, Northmen, and Slavs: identities and state formation in early medieval Europe. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 55–60. ISBN 9782503526157. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ Łoziński, Jerzy Z.; Miłobędzki, Adam (1967). Guide to Architecture in Poland. Warszawa (Warsaw): Polonia Publishing House. p. 13. OCLC 429768. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Dabrowski, Patrice (2014). Poland: The First Thousand Years. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-5017-5740-2.

- ^ a b Ramet, Sabrina (2017). The Catholic Church in Polish History. From 966 to the Present. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-137-40281-3. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (2016). Great Events in Religion. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 468, 480–481. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Gerard Labuda (1992). Mieszko II król Polski: 1025–1034: czasy przełomu w dziejach państwa polskiego. Secesja. p. 112. ISBN 978-83-85483-46-5. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2011). Religious Celebrations. An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 834. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ^ Hourihane, Colum (2012). The Grove encyclopedia of medieval art and architecture. Vol. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Krasuski, Jerzy (2009). Polska-Niemcy. Stosunki polityczne od zarania po czasy najnowsze. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 53. ISBN 978-83-04-04985-7. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Maroń, Jerzy (1996). Legnica 1241 (in Polish). Warszawa (Warsaw): Bellona. ISBN 978-83-11-11171-4. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Dembkowski, Harry E. (1982). The union of Lublin, Polish federalism in the golden age. East European Monographs. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-88033-009-1. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Pac, Teresa (2022). Common Culture and the Ideology of Difference in Medieval and Contemporary Poland. Lexington Books. p. 22. ISBN 9781793626929. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Biber, Tomasz; Leszczyński, Maciej (2000). Encyklopedia Polska 2000. Poczet władców. Poznań: Podsiedlik-Raniowski. p. 47. ISBN 978-83-7212-307-7. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Kula, Marcin (2000). Zupełnie normalna historia, czyli, Dzieje Polski zanalizowane przez Marcina Kulę w krótkich słowach, subiektywnie, ku pożytkowi miejscowych i cudzoziemców. Warszawa (Warsaw): Więzi. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-83-88032-27-1. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Stanley S. Sokol (1992). The Polish Biographical Dictionary: Profiles of Nearly 900 Poles who Have Made Lasting Contributions to World Civilization. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-86516-245-7.

- ^ a b c Stone, Daniel (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 10, 16. ISBN 9780295980935. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Boggis-Rolfe, Caroline (2019). The Baltic Story. A Thousand-Year History of Its Lands, Sea and Peoples. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445688510. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Łupienko, Aleksander (2024). Urban Communities and Memories in East-Central Europe in the Modern Age. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781040111055. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Bill, Stanley; Lewis, Simon (2023). Multicultural Commonwealth. Pittsburgh: University Press. ISBN 9780822990192. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Butterwick-Pawlikowski, Richard (2012). The Polish Revolution and the Catholic Church, 1788-1792. Oxford: University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780199250332. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Roszkowski, Wojciech (2015). East Central Europe. Warszawa (Warsaw): Instytut Jagielloński. p. 69. ISBN 9788364091483. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Allen, Rowan; Rose, Denny (2018). History of Europe. EDTECH. p. 23. ISBN 9781839472787. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Rundell, Benedict (2015). Common Wealth, Common Good. The Politics of Virtue in Early Modern Poland-Lithuania. Oxford: University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780198735342. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Ascherson, Neal (1987). The struggles for Poland. New York: Random House. p. 20. ISBN 9780394559971. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Rundell, Benedict (2015). Common Wealth, Common Good. The Politics of Virtue in Early Modern Poland-Lithuania. Oxford: University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780198735342. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Rundell, Benedict (2015). Common Wealth, Common Good. The Politics of Virtue in Early Modern Poland-Lithuania. Oxford: University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780198735342. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Bertholet, Auguste (2021). "Constant, Sismondi et la Pologne". Annales Benjamin Constant. 46: 65–85. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Piotr S. Wandycz (2009). "The Second Republic, 1921–1939". The Polish Review. 54 (2). University of Illinois Press: 159–171. JSTOR 25779809.

- ^ Robert Machray (November 1930). "Pilsudski, the Strong Man of Poland". Current History. 33 (2). University of California Press: 195–199. doi:10.1525/curh.1930.33.2.195. JSTOR 45333442.

- ^ Brian Porter-Szücs (6 January 2014). Poland in the Modern World: Beyond Martyrdom. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-59808-5.

- ^ Moorhouse, Roger (2019). First to Fight. The Polish War 1939. London: Bodley Head. ISBN 9781473548220. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Spencer C. (2016). World War II. The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1343, 1863. ISBN 9781851099696. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Gwiazda, Anna (2015). Democracy in Poland. Representation, Participation, Competition and Accountability Since 1989. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781317396208. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d Źrałka, Edyta (2019). Manipulation in Translating British and American Press Articles in the People’s Republic of Poland. Newcastle upon Tyne: CSP. pp. 87–244. ISBN 9781527538528. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Administration of George Bush (1990). Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: George Bush, 1989. Washington D.C.: US GPO. OCLC 968376615. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Jain, Rajendra Kumar (2024). Poland and South Asia: deepening engagement. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 299–300. ISBN 9789819710218. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way: A Thousand Year History of the Poles and Their Culture Archived 28 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Published 1993, Hippocrene Books, Poland, ISBN 0-7818-0200-8

- ^ Rocca, Francis X.; Ojewska, Natalia (19 February 2022). "In Traditionally Catholic Poland, the Young Are Leaving the Church". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Graf Strachwitz, Rupert (2020). Religious communities and civil society in Europe. Vol. II. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenburg. p. 177. ISBN 978-3-11-067299-2. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Zarnowski, Janusz (2024). State, Society and Intelligentsia. Modern Poland and Its Regional Context. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781040244173. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b (in Polish) Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Archived 1 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine [(in English) Constitution of the Republic of Poland Archived 15 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine], Dz.U. 1997 nr 78 poz. 483

- ^ a b Aniskiewicz, Alena (2016). "That's Polish: Exploring the History of Poland's National Emblems". culture.pl. Government of Poland; Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Mętrak-Ruda, Natalia (2019). "Crisp & Sweet: Polish Apple Culture". culture.pl. Government of Poland; Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b "Zalecenia dla urzędów stanu cywilnego". rjp.pan.pl (in Polish). Rada Języka Polskiego. 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Gliński, Mikołaj (2015). "Imieniny – Poland Word by Word". culture.pl. Government of Poland; Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Gliński, Mikołaj (2016). "A Foreigner's Guide to Polish Surnames". culture.pl. Government of Poland; Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Zarębski, Rafał (2013). Studia Ceranea; Possessive Adjectives Formed from Personal Names in Polish Translations of the New Testament. Vol. 3. Łódź: Journal of the Waldemar Ceran Research Centre for the History and Culture of the Mediterranean Area and South-East Europe. pp. 187–196. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Hajduk, Jarek. "Present Tense - Verbs conjugation". courseofpolish.com. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Cabrera, Isabel (2020). "World Reading Habits in 2020 [Infographic]". geediting.com. Global English Editing. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Knoll, Paul W.; Schaer, Frank, eds. (2003), Gesta Principum Polonorum / The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles, Central European Medieval Texts, General Editors János M. Bak, Urszula Borkowska, Giles Constable & Gábor Klaniczay, vol. 3, Budapest/ New York: Central European University Press, pp. 87–211, ISBN 978-963-9241-40-4

- ^ a b "Polish Libraries – Wiesław Wydra: The Oldest Extant Prose Text in the Polish language. The Phenomenon of the Holy Cross Sermons". polishlibraries.pl. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Dwujęzyczność w twórczości Jana Kochanowskiego". fp.amu.edu.pl.

- ^ "PISA 2018 results". oecd.org. OECD. 2018. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Zachara, Małgorzata (2018). Poland in Transatlantic Relations after 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-5275-0740-1.

- ^ a b Materka, Edyta (2017). Dystopia's Provocateurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9780253029096. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Nodzyńska, Małgorzata; Cieśla, Paweł (2012). From Alchemy to the Present Day – the Choice of Biographies of Polish Scientists. Cracow: Pedagogical University of Kraków. ISBN 978-83-7271-768-9. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ a b Gameiro, Marcelo (2024). The World in Your Hands. Vol. 7. MGameiro LLC. ISBN 9798882259142. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Silverman, Deborah Anders (2000). Polish-American Folklore. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 141–146. ISBN 9780252025693. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Berend, Ivan T. (2005). History Derailed. Central and Eastern Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-520-24525-9.

- ^ Sturman, Janet (2019). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. pp. 1704–1705. ISBN 9781483317748. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Wilson, Thomas M. (2023). Europe. An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 715–716. ISBN 9798216171409. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Thomas M. (2023). Europe. An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 716–717. ISBN 9798216171409. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Stone, Daniel Z. (2014). The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780295803623. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Tobey, Julie. "Exploring Poland's Diverse Art Scene". polishculture-nyc.org. Polish Culture NYC. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Anderson, Dale (2006). Polish Americans. Milwaukee: World Almanac Library. p. 13. ISBN 9780836873177. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Sznajder, Anna (2019). Polish Lace Makers. Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 275. ISBN 9781498584326. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Barbara Kaznowska, Bohdan Sowilski, Bohdan Czarnecki, Małgorzata Orlewicz (1984). Polish Folk Costumes. Warszawa (Warsaw): State Ethnographical Museum. ISBN 9788300009398. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ culture.pl (2016). "A Typical Daily Menu in Poland". Government of Poland; Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Allen, Gregory; Lipska, Magdalena (2023). Poland - Culture Smart! The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture. Kuperard. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Eurostat (2019). "Overweight and obesity - BMI statistics". ec.europa.eu. European Union. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2017). "Food balances data 2017". FAO.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "WHO Global status report on alcohol and health 2018" (PDF). who.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Europe: Poland — the World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ GUS, Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludnosci 2011: 4.4. Przynależność wyznaniowa (National Survey 2011: 4.4 Membership in faith communities) Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine p. 99/337 (PDF file, direct download 3.3 MB). ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1 Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ (in Polish) Kościoły i związki wyznaniowe w Polsce Archived 5 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ Scott Simpson, Native Faith: Polish Neo-Paganism at the Brink of the 21st Century, 2000.

- ^ "Countries in the EU by Population (2025)". Worldometer. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ GUS. "Tablice z ostatecznymi danymi w zakresie przynależności narodowo-etnicznej, języka używanego w domu oraz przynależności do wyznania religijnego; spis 2021". stat.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ Kruszka, Wacław (1905). Historya Polska w Ameryce. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Spółka Wydawnicza Kuryera.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ ""Sueddeutsche Zeitung": Polska przeżywa największą falę emigracji od 100 lat". Wiadomosci.onet.pl. 26 September 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Polish - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2022.