Plato

Plato | |

|---|---|

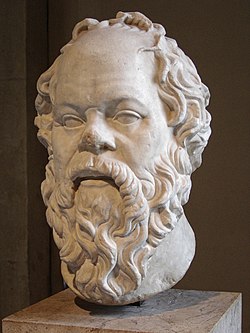

Roman copy of a portrait bust c. 370 BC | |

| Born | 428/427 or 424/423 BC |

| Died | 348/347 BC Athens |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | Ancient Greek philosophy |

| Notable students | Aristotle |

| Main interests | Epistemology, Metaphysics Political philosophy |

| Notable works | |

| Notable ideas | |

Plato (/ˈpleɪtoʊ/ PLAY-toe; Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn; born c. 428–423 BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the written dialogue and dialectic forms. He influenced all the major areas of theoretical philosophy and practical philosophy, and was the founder of the Platonic Academy, a philosophical school in Athens where Plato taught the doctrines that would later become known as Platonism.

Plato's most famous contribution is the theory of forms (or ideas), which aims to solve what is now known as the problem of universals. He was influenced by the pre-Socratic thinkers Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, although much of what is known about them is derived from Plato himself.

Along with his teacher Socrates, and his student Aristotle, Plato is a central figure in the history of Western philosophy. Plato's complete works are believed to have survived for over 2,400 years—unlike that of nearly all of his contemporaries.[1] Although their popularity has fluctuated, they have consistently been read and studied through the ages.[2] Through Neoplatonism, he also influenced both Christian and Islamic philosophy. In modern times, Alfred North Whitehead said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[3]

Life

Plato was born between 428 and 423 BC[4][5] into an aristocratic and influential Athenian family;[6] through his mother, Perictione, he was a descendant of Solon, a statesman credited with laying the foundations of Athenian democracy.[7] There is an apocryphal story that Plato is a nickname, and that his birth name was Aristocles (Ἀριστοκλῆς), meaning 'best reputation', but this is widely regarded as false by modern scholarship.[8][9][10][5] Plato had two brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, both of whom appear in the Republic, and also a sister, Potone, and a half brother, Antiphon.[5]

During Plato's childhood, Athens was involved in the Peloponessian War against Sparta. His older brothers, Adeimantus and Glaucon, distinguished themselves at the battle of Megara in 409 BC.[11] Despite the war, Plato and his brothers, like all male citizens of Athens, received a traditional education in gymnastics and music.[12] According to the ancient writers, there was a tradition that Plato's favorite employment in his youthful years was poetry: he wrote poems, dithyrambs at first, and afterwards lyric poems and tragedies (a tetralogy), but abandoned his early passion and burnt his poems when he met Socrates and turned to philosophy.[13] There are also some epigrams attributed to Plato, but these are now thought by some scholars to be spurious.[14]

Socrates

In his youth, Plato first encountered Socrates, who would become his teacher and greatest source of inspiration, initially in the company of other Athenian boys in the Palaestra, such as is depicted with Lysis and Menexenus, who discuss philosophy with Socrates in the Lysis,[15] but he soon would become a member of Socrates' inner circle, meeting with Socrates and his other followers. Socrates, along with the sophists of his day, challenged the prevailing focus of Early Greek philosophy on Natural philosophy, and investigated questions of ethics and politics, examining the ideas of his interlocutors with a series of questioning called the Socratic method.[16]

Socrates' immense influence on Plato is clearly borne out in Plato's dialogues: Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues; every dialogue except the Laws features Socrates, although many dialogues, including the Timaeus and Statesman, feature him speaking only rarely. Leo Strauss notes that Socrates' reputation for irony casts doubt on whether Plato's Socrates is expressing sincere beliefs.[17] Xenophon's Memorabilia and Aristophanes's The Clouds seem to present a somewhat different portrait of Socrates from the one Plato paints. Aristotle attributes a different doctrine with respect to Forms to Plato and Socrates.[18] Aristotle suggests that Socrates' idea of forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural world, unlike Plato's Forms that exist beyond and outside the ordinary range of human understanding.[19] The Socratic problem concerns how to reconcile these various accounts. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars.[20][page needed]

Thirty tyrants and Trial of Socrates

According to the Seventh Letter, whose authenticity has been disputed, as Plato came of age, he imagined for himself a life in public affairs.[21] In 404, Sparta defeated Athens at the conclusion of the Peloponessian war, leading to the election of the Thirty Tyrants, which included two of Plato's relatives, Critias and Charmides.[22] Plato himself was invited to join the administration, but declined, and quickly became disillusioned by the atrocities committed by the Thirty, especially when they tried to implicate Socrates in their seizure of the democratic general Leon of Salamis for summary execution.[23]

In 403 BC, the democracy was restored after the regrouping of the democrats in exile, who entered the city through the Piraeus and met the forces of the Thirty at the Battle of Munychia, where both Critias and Charmides were killed. In 401 BC the restored democrats raided Eleusis and killed the remaining oligarchic supporters, suspecting them of hiring mercenaries.[24]

As depicted in the many dialogues that are set between 401 and 399 BC, life largely returned to normal in Athens. However, the prosecution of Socrates by Anytus put an end to his plans.[25]

Later philosophical development

After the death of Socrates, Plato remained in Athens for roughly three years.[26]

Heraclitus and Parmenides

In Athens, Plato studied with Cratylus, a philosopher who followed the early Greek philosopher Heraclitus, and also Hermogenes, an Eleatic philosopher in the tradition of Parmenides.[27] Heraclitus viewed all things as continuously changing, that one cannot "step into the same river twice" due to the ever-changing waters flowing through it, and all things exist as a contraposition of opposites, while Parmenides adopted an altogether contrary vision, arguing for the idea of a changeless, eternal universe and the view that change is an illusion. Heraclitus's views are expounded by Cratylus himself in Plato's dialogue Cratylus and deconstructed in the Theaetetus by Socrates. Plato would go on to depict both Parmenides and Parmenides' student Zeno in the Parmenides, and an "Eleatic Stranger" also appears in the Sophist and Statesman.

In roughly 396 BC, Plato left Athens and studied in Megara with Euclid of Megara, founder of the Megarian school of philosophy, and other Socratics.[28]

Mathematics

Around 394 BC or earlier, he returned to Athens, where, as an Athenian male of military age he would have needed to be available to serve in the Corinthian war, which Athens participated in from 395 to 386 BC.[29] Other than potential military service, Plato spent his time studying mathematics with Archytas of Tarentum, Theaetetus, Leodamas of Thasos, and Neoclides in the grove of Hecademus,[30] named after an Attic hero in Greek mythology, northwest of the city of Athens, where he would later found his Academy.[5] During this time, Plato likely began work on some of his earliest works; including the Apology, possibly early drafts of the Gorgias and Republic Book I, and an early form of the Republic books II-IV, in the form of a speech rather than a dialogue, which was ridiculed by Aristophanes in the Ecclesiazusae in 391 BC.[31] Speusippus, the son of Plato's sister Potone, who took over the academy after Plato's death, joined the group in about 390 BC, and Eudoxus of Cnidus, another early mathematician, arrived around 385 BC.[30]

Pythagoreanism

After the conclusion of the Corinthian War, Plato travelled to southern Italy to study with Archytas and other Pythagoreans.[32] The influence of these Pythagoreans appears to have been significant. According to R. M. Hare, this influence consists of three points:

- The platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton.

- The idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals".

- They shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world".[33]

Pythagoras held that all things are number, and the cosmos comes from numerical principles. He introduced the concept of form as distinct from matter, and that the physical world is an imitation of an eternal mathematical world.[34]

Later years: Syracuse and the Academy

First trip to Syracuse

When Plato was about 40 years old, he visited Syracuse. Many Ancient sources, including the collection of Letters attributed to Plato, tell how he became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse. Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysius, in roughly 385 BC.[35] During this first trip Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato.[5]

Foundation of the Academy

After his return from Syracuse, Plato founded his philosophical school, the Academy, near the sacred olive grove of Hecademus, in roughly 383 BC.[27] At first, the property consisted of only a house with a garden, and during his lifetime, the work of the Academy itself likely took part an open area for study of philosophy and mathematics.[27] From 383 BC until about 366 BC, Plato primarily spent his time at the Academy, writing the majority of the dialogues during this time.[36] Much like Socrates and his students had been parodied in Aristophanes' plays The Clouds and The Birds, the students at the Academy seem to have been the target of their contemporaries in Middle Comedy.[27] A fragment from a lost play of Epicrates depicts two students of the Academy engaged in a fierce debate over the genus of a pumpkin, in a parody of the Platonic conception of diairesis.[27] Aristotle of Stagira, who would go on to become a philosopher as famous as Plato in his own right,[37] arrived in 367 BC, shortly before Plato departed again for Syracuse.[38]

Second and third trip to Syracuse

After Dionysius I's death in 367 BC, Plato returned to Syracuse, likely early in 366 BC, at the request of Dion, in order to tutor Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysius expelled Dion, and Plato, after trying repeatedly to reconcile the two, gave up and returned to Athens.[27]

Plato returned to Syracuse a third time in 361 BC, likely staying over the winter until 360 BC.[27] Dionysius kept Plato against his will, forcing Plato to appeal to his friend Archytas to intercede, at which point he returned to Athens.[27] Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and ruled Syracuse for a short time in 357 BC up until 354 BC,[27] when he was usurped by Calippus, an Athenian who Plato insists, in the Seventh Letter, had no connection with the Academy.[39]

Final years and death

After 360 BC, Plato returned to Athens, where he spent the remainder of his life.[5]

At this point, he wrote or revised some of his final works, possibly including the Timaeus, Critias, Sophist, Statesman, Philebus, and his longest work, the Laws, all of which exhibit similarity of language, philosophical themes, and style that indicate they were intentionally published together to present a unified viewpoint.[40] At the time of his death, however, the Laws was still unfinished; this work was edited by a student at the Academy, Philip of Opus, who is also generally believed to have written the Epinomis, an appendix to the Laws.[41]

In 348/347 BC, Plato died and was buried in his garden in the Academy in Athens.[42] At the time of his death, Plato seems to have been self-sufficient, but not wealthy.[43] A will preserved by one of the ancient biographers of Plato, which discusses his estate, does not mention the Academy, which suggests that he left a separate provision for it or possibly established an endowment.[44] He was succeeded as the head of the Academy by Speusippus, his nephew.[41]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The Republic |

| Timaeus |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates and his company of disputants had something to say on many subjects, including several aspects of metaphysics. These include religion and science, human nature, love, and sexuality. More than one dialogue contrasts perception and reality, nature and custom, and body and soul. Francis Cornford identified the "twin pillars of Platonism" as the theory of Forms, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the doctrine of immortality of the soul.[45]

The Forms

In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning of a general term (e. g. justice, truth, beauty), and criticizes those who instead give him particular examples, rather than the quality shared by all examples. "Platonism" and its theory of Forms (also known as 'theory of Ideas') denies the reality of the material world, considering it only an image or copy of the real world. According to this theory of Forms, there are these two kinds of things: the apparent world of material objects grasped by the senses, which constantly changes, and an unchanging and unseen world of Forms, grasped by reason (λογική). Plato's Forms represent types of things, as well as properties, patterns, and relations, which are referred to as objects. Just as individual tables, chairs, and cars refer to objects in this world, 'tableness', 'chairness', and 'carness', as well as e.g. justice, truth, and beauty refer to objects in another world. One of Plato's most cited examples for the Forms were the truths of geometry, such as the Pythagorean theorem. The theory of Forms is first introduced in the Phaedo dialogue (also known as On the Soul), wherein Socrates disputes the pluralism of Anaxagoras, then the most popular response to Heraclitus and Parmenides.

The Soul

For Plato, as was characteristic of ancient Greek philosophy, the soul was that which gave life. Plato advocates a belief in the immortality of the soul, and several dialogues end with long speeches imagining the afterlife. In the Timaeus, Socrates locates the parts of the soul within the human body: Reason is located in the head, spirit in the top third of the torso, and the appetite in the middle third of the torso, down to the navel.[46]

Furthermore, Plato evinces a belief in the theory of reincarnation in multiple dialogues (such as the Phaedo and Timaeus). Scholars debate whether he intends the theory to be literally true, however.[47] He uses this idea of reincarnation to introduce the concept that knowledge is a matter of recollection of things acquainted with before one is born, and not of observation or study.[48] Keeping with the theme of admitting his own ignorance, Socrates regularly complains of his forgetfulness. In the Meno, Socrates uses a geometrical example to expound Plato's view that knowledge in this latter sense is acquired by recollection. Socrates elicits a fact concerning a geometrical construction from a slave boy, who could not have otherwise known the fact (due to the slave boy's lack of education). The knowledge must be of, Socrates concludes, an eternal, non-perceptible Form.

Epistemology

Plato also discusses several aspects of epistemology. In several dialogues, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition about what is knowable and what is real. Reality is unavailable to those who use their senses. Socrates says that he who sees with his eyes is blind. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In other words, such people are willingly ignorant, living without divine inspiration and access to higher insights about reality. Although Plato has occasionally been presented as having been the first to write – that knowledge is justified true belief in the Theaetetus,[49] Plato also identified problems with this same justified true belief definition in that same work, concluding that justification (or an "account") would require knowledge of difference, meaning that the definition of knowledge is circular.[50]

In the Sophist, Statesman, Republic, Timaeus, and the Parmenides, Plato associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in dialectic), including through the processes of collection and division.[51] More explicitly, Plato himself argues in the Timaeus that knowledge is always proportionate to the realm from which it is gained. In other words, if one derives one's account of something experientially, because the world of sense is in flux, the views therein attained will be mere opinions. Meanwhile, opinions are characterized by a lack of necessity and stability. On the other hand, if one derives one's account of something by way of the non-sensible Forms, because these Forms are unchanging, so too is the account derived from them. That apprehension of Forms is required for knowledge may be taken to cohere with Plato's theory in the Theaetetus and Meno.[52] Indeed, the apprehension of Forms may be at the base of the account required for justification, in that it offers foundational knowledge which itself needs no account, thereby avoiding an infinite regression.[53]

Ethics

Several dialogues discuss ethics including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime and punishment, and justice and medicine. Socrates presents the famous Euthyphro dilemma in the dialogue of the same name: "Is the pious (τὸ ὅσιον) loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" (10a) In the Protagoras dialogue it is argued through Socrates that virtue is innate and cannot be learned, that no one does bad on purpose, and to know what is good results in doing what is good; that knowledge is virtue. In the Republic, Plato poses the question, "What is justice?" and by examining both individual justice and the justice that informs societies, Plato is able not only to inform metaphysics, but also ethics and politics with the question: "What is the basis of moral and social obligation?" Plato's well-known answer rests upon the fundamental responsibility to seek wisdom, wisdom which leads to an understanding of the Form of the Good. Plato views "The Good" as the supreme Form, somehow existing even "beyond being". In this manner, justice is obtained when knowledge of how to fulfill one's moral and political function in society is put into practice.

Politics

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the Republic as well as in the Laws and the Statesman. Because these opinions are not spoken directly by Plato and vary between dialogues, they cannot be straightforwardly assumed as representing Plato's own views.

Socrates asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.[54]

- Productive (Workers) – the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

- Protective (Warriors or Guardians) – those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

- Governing (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) – those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to Socrates, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honourable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant).[55]

Rhetoric and poetry

Several dialogues tackle questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus,[56] and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. Scholars often view Plato's philosophy as at odds with rhetoric due to his criticisms of rhetoric in the Gorgias and his ambivalence toward rhetoric expressed in the Phaedrus. But other contemporary researchers contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles.[57] Plato made abundant use of mythological narratives in his own work; it is generally agreed that the main purpose for Plato in using myths was didactic.[58] He considered that only a few people were capable or interested in following a reasoned philosophical discourse, but men in general are attracted by stories and tales. Consequently, then, he used the myth to convey the conclusions of the philosophical reasoning.[59] Notable examples include the story of Atlantis, the Myth of Er, and the Allegory of the Cave.

Unwritten doctrines

Plato's unwritten doctrines are,[60] according to some ancient sources, the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public, although many modern scholars[who?] doubt these claims. It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture On the Good (Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ), in which the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) is identified with the One (the Unity, τὸ ἕν), the fundamental ontological principle. The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the Neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus. All the sources related to the ἄγραφα δόγματα have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as Testimonia Platonica.[61]

Works

Themes

Plato never presents himself as a participant in any of the dialogues, and with the exception of the Apology, there is no suggestion that he heard any of the dialogues firsthand. Some dialogues have no narrator but have a pure "dramatic" form, some dialogues are narrated by Socrates himself, who speaks in the first person. The Symposium is narrated by Apollodorus, a Socratic disciple, apparently to Glaucon. Apollodorus assures his listener that he is recounting the story, which took place when he himself was an infant, not from his own memory, but as remembered by Aristodemus, who told him the story years ago. In most of the dialogues, the primary speaker is Socrates, who employs a method of questioning which proceeds by a dialogue form.

Textual sources and history

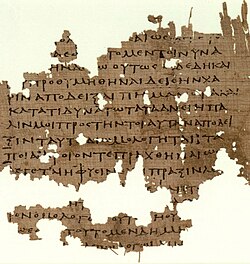

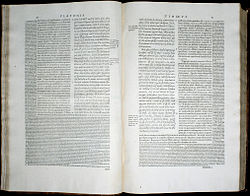

During the early Renaissance, the Greek language and, along with it, Plato's texts were reintroduced to Western Europe by Byzantine scholars. Some 250 known Byzantine manuscripts of Plato survive.[62] In September or October 1484 Filippo Valori and Francesco Berlinghieri printed 1025 copies of Ficino's translation.[63] The 1578 edition of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres). It was this edition which established standard Stephanus pagination, still in use today. The text of Plato as received today apparently represents the complete written philosophical work of Plato, based on the first century AD arrangement of Thrasyllus of Mendes.[64] Since the beginning of the 20th century, many papyri from the Hellenistic period through the third century AD containing text from Plato's dialogues have also been recovered from Egypt, which provide important early witnesses to the text.[62] The modern standard complete English edition is the 1997 Hackett Plato: Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper.[65][66]

Authenticity

Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles) have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. There is a broad consensus among scholarship to doubt the authenticity of Alcibiades II, Epinomis, Hipparchus, Minos, Lovers, and Theages, while the opinion on Alcibiades I,Clitophon, Letters, and Menexenus is more divided.[67] The following works were transmitted under Plato's name in antiquity, but were already considered spurious by the 1st century AD: Axiochus, Definitions, Demodocus, Epigrams, Eryxias, Halcyon, On Justice, On Virtue, Sisyphus.[65]

Chronology

No one knows the exact order Plato's dialogues were written in, nor the extent to which some might have been later revised and rewritten. The works are usually grouped into Early, Middle, and Late period; The following represents one relatively common division amongst developmentalist scholars.[68]

- Early: Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthyphro, Gorgias, Hippias Minor, Hippias Major, Ion, Laches, Lysis, Protagoras

- Middle: Cratylus, Euthydemus, Meno, Parmenides, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Republic, Symposium, Theatetus

- Late: Critias, Sophist, Statesman, Timaeus, Philebus, Laws.

Whereas those classified as "early dialogues" often conclude in aporia, the so-called "middle dialogues" provide more clearly stated positive teachings that are often ascribed to Plato such as the theory of Forms. The remaining dialogues are classified as "late" and are generally agreed to be difficult and challenging pieces of philosophy.[69] It should, however, be kept in mind that many of the positions in the ordering are still highly disputed, and also that the very notion that Plato's dialogues can or should be "ordered" is by no means universally accepted,[65] Increasingly in the most recent Plato scholarship, writers are skeptical of the notion that the order of Plato's writings can be established with any precision.[70] though Plato's works are still often characterized as falling at least roughly into three groups stylistically.

Legacy

Medieval era

During the Islamic Golden ages, Neoplatonism was revived from its founding father, Plotinus.[71] Neoplatonism, a philosophical current that permeated Islamic scholarship, accentuated one facet of the Qur’anic conception of God—the transcendent—while seemingly neglecting another—the creative. This philosophical tradition, introduced by Al-Farabi and subsequently elaborated upon by figures such as Avicenna, postulated that all phenomena emanated from the divine source.[72] It functioned as a conduit, bridging the transcendental nature of the divine with the tangible reality of creation. In the Islamic context, Neoplatonism facilitated the integration of Platonic philosophy with mystical Islamic thought, fostering a synthesis of ancient philosophical wisdom and religious insight.[72] Inspired by Plato's Republic, Al-Farabi extended his inquiry beyond mere political theory, proposing an ideal city governed by philosopher-kings.[73] Plato is also referenced by Jewish philosopher and Talmudic scholar Maimonides in his Guide for the Perplexed.

Many of these commentaries on Plato were translated from Arabic into Latin, in which form they influenced medieval scholastics.[74][75] Plato's thought is often compared with that of his most famous student, Aristotle, whose reputation during the Western Middle Ages so completely eclipsed that of Plato that the Scholastic philosophers referred to Aristotle as "the Philosopher". The only Platonic work known to western scholarship was Timaeus, until translations into Latin were made beginning in the 12th century. However, the study of Plato continued in the Byzantine Empire, the Caliphates during the Islamic Golden Age, and Spain during the Golden age of Jewish culture.

Modern

During the Renaissance, Gemistos Plethon brought Plato's original writings to Florence from Constantinople in the century of its fall. Many of the greatest early modern scientists and artists who broke with Scholasticism, with the support of the Plato-inspired Lorenzo (grandson of Cosimo), saw Plato's philosophy as the basis for progress in the arts and sciences. The 17th century Cambridge Platonists sought to reconcile Plato's more problematic beliefs, such as metempsychosis and polyamory, with Christianity.[76] By the 19th century, Plato's reputation was restored, and at least on par with Aristotle's. Plato's influence has been especially strong in mathematics and the sciences. Plato's resurgence further inspired some of the greatest advances in logic since Aristotle, primarily through Gottlob Frege. Albert Einstein suggested that the scientist who takes philosophy seriously would have to avoid systematization and take on many different roles, and possibly appear as a Platonist or Pythagorean, in that such a one would have "the viewpoint of logical simplicity as an indispensable and effective tool of his research."[77] British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[3][78] Adapting examples from Plato's Theaetetus, Edmund Gettier famously demonstrated the Gettier problem for the "justified true belief account" of knowledge, challenging the prevelant notion in Analytic philosophy at the time that had been popularized by A. J. Ayer.[79]

Notes

- ^ Cooper 1997, introduction.

- ^ Cooper 1997, p. vii.

- ^ a b Whitehead 1978, p. 39.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d e f Waterfield 2023.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Stanton, G. R. Athenian Politics c. 800–500 BC: A Sourcebook, Routledge, London (1990), p. 76.

- ^ Notopoulos 1939, pp. 135–145.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 243.

- ^ Guthrie 1986, p. 12 (footnote).

- ^ Nails 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, pp. 14–19.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Strauss 1964, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Metaphysics 987b1–11

- ^ McPherran, M.L. (1998). The Religion of Socrates. Penn State Press. p. 268.

- ^ Vlastos 1991.

- ^ Plato (?), Seventh Letter, 324c

- ^ Nails 2006, p. 2-3.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 65-66.

- ^ Nails 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 66.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nails 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 72.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 73.

- ^ a b Nails 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Nails 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 112.

- ^ R.M. Hare, Plato in C.C.W. Taylor, R.M. Hare and Jonathan Barnes, Greek Philosophers, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 (1982), 103–189, here 117–119.

- ^ Calian, Florin George (2021). Numbers, Ontologically Speaking: Plato on Numerosity. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-46722-4. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Riginos 1976, p. 73.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Dillon 2003, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Nails 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Nails 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Waterfield 2023, p. 87.

- ^ a b Nails 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 249.

- ^ Nails 2002, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 249-250.

- ^ Francis Cornford, 1941. The Republic of Plato. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xxv.

- ^ Dorter 2006, p. 360.

- ^ Jorgenson 2018.

- ^ Baird & Kaufmann 2008.

- ^ Fine 2003, p. 5.

- ^ McDowell 1973, p. 256.

- ^ Taylor 2011, pp. 176–187.

- ^ Lee 2011, p. 432.

- ^ Taylor 2011, p. 189.

- ^ Blössner 2007, pp. 345–349.

- ^ Blössner 2007, p. 350.

- ^ Phaedrus (265a–c)

- ^ Kastely 2015.

- ^ Jorgenson 2018, p. 199.

- ^ Partenie, Catalin. "Plato's Myths". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Reale 1990, p. 14f.

- ^ Gaiser 1998.

- ^ a b Brumbaugh & Wells 1989.

- ^ Allen 1975, p. 12.

- ^ Cooper 1997, pp. viii–xii.

- ^ a b c Cooper 1997.

- ^ Fine 1999a, p. 482.

- ^ Cooper 1997, pp. v–vi.

- ^ Fine 1999b.

- ^ Cooper 1997, p. xiv.

- ^ Kraut 2013.

- ^ Willinsky, John (2018). The Intellectual Properties of Learning: A Prehistory from Saint Jerome to John Locke (1st ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press (published 2 January 2018). pp. Chapter 6. ISBN 978-0226487922.

- ^ a b Aminrazavi 2021.

- ^ Stefaniuk, Tomasz (5 December 2022). "Man in Early Islamic Philosophy – Al-Kindi and Al-Farabi". Ruch Filozoficzny. 78 (3): 65–84. doi:10.12775/RF.2022.023. ISSN 2545-3173.

- ^ Burrell 1998.

- ^ Hasse 2002, pp. 33–45.

- ^ Carrigan, Henry L. Jr. (2012) [2011]. "Cambridge Platonists". The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9780470670606.wbecc0219. ISBN 978-1405157629.

- ^ Einstein 1949, pp. 683–684.

- ^ "A.N Whitehead on Plato". Columbia College. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023.

- ^ Gettier, E. L. (1 June 1963). "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?". Analysis. 23 (6): 121–123. doi:10.1093/analys/23.6.121.

References

- Allen, Michael J.B. (1975). "Introduction". Marsilio Ficino: The Philebus Commentary. University of California Press. pp. 1–58.

- Aminrazavi, Mehdi (2021). "Mysticism in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Baird, Forrest E.; Kaufmann, Walter, eds. (2008). Philosophic Classics: From Plato to Derrida (Fifth ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-158591-1.

- Blössner, Norbert (2007). "The City-Soul Analogy". In Ferrari, G.R.F. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Plato's Republic. Translated by G.R.F. Ferrari. Cambridge University Press.

- Brumbaugh, Robert S.; Wells, Rulon S. (October 1989). "Completing Yale's Microfilm Project". The Yale University Library Gazette. 64 (1/2): 73–75. JSTOR 40858970.

- Burrell, David (1998). "Platonism in Islamic Philosophy". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 7. Routledge. pp. 429–430.

- Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S., eds. (1997). Plato: Complete Works. Hackett Publishing.

- Dillon, John (2003). The Heirs of Plato: A Study of the Old Academy. Oxford University Press.

- Dorter, Kenneth (2006). The Transformation of Plato's Republic. Lexington Books.

- Einstein, Albert (1949). "Remarks to the Essays Appearing in this Collective Volume". In Schilpp (ed.). Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist. The Library of Living Philosophers. Vol. 7. MJF Books. pp. 663–688.

- Fine, Gail (1999a). "Selected Bibliography". Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 481–494.

- Fine, Gail (1999b). "Introduction". Plato 2: Ethics, Politics, Religion, and the Soul. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–33.

- Fine, Gail (2003). "Introduction". Plato on Knowledge and Forms: Selected Essays. Oxford University Press.

- Gaiser, Konrad (1998). Reale, Giovanni (ed.). Testimonia Platonica: Le antiche testimonianze sulle dottrine non scritte di Platone. Milan: Vita e Pensiero.

- Guthrie, W.K.C. (1986). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 4, Plato: The Man and His Dialogues: Earlier Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31101-4.

- Hasse, Dag Nikolaus (2002). "Plato Arabico-latinus". In Gersh; Hoenen (eds.). The Platonic Tradition in the Middle Ages: A Doxographic Approach. De Gruyter. pp. 33–66.

- Jorgenson, Chad (5 April 2018). The Embodied Soul in Plato's Later Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-80052-2. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- Kastely, James L. (25 August 2015). The Rhetoric of Plato's Republic: Democracy and the Philosophical Problem of Persuasion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-27876-6. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- Kraut, Richard (11 September 2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Plato". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Lee, M.-K. (2011). "The Theaetetus". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press. pp. 411–436.

- McDowell, J. (1973). Plato: Theaetetus. Oxford University Press.

- Nails, Debra (2002). The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-564-2.

- Nails, Debra (2006). "The Life of Plato of Athens". A Companion to Plato edited by Hugh H. Benson. Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9780470996256.ch1. ISBN 1-4051-1521-1.

- Notopoulos, A. (April 1939). "The Name of Plato". Classical Philology. 34 (2): 135–145. doi:10.1086/362227. S2CID 161505593.

- Reale, Giovanni (1990). Catan, John R. (ed.). Plato and Aristotle. A History of Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 2. State University of New York Press.

- Riginos, Alice (1976). Platonica : the anecdotes concerning the life and writings of Plato. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04565-1.

- Strauss, Leo (1964). The City and the Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Taylor, C.C.W. (2011). "Plato's Epistemology". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press. pp. 165–190.

- Vlastos, Gregory (1991). Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher. Cambridge University Press.

- Waterfield, Robin (2023). Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-756475-2. Retrieved 5 May 2025.

- Whitehead, Alfred North (1978). Process and Reality. New York: The Free Press.

External links

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Platon

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Platon- Works available online:

- Works by Plato in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Plato at Perseus Project – Greek & English hyperlinked text

- Works by Plato at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Plato at the Internet Archive

- Works by Plato at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Other resources:

- Plato at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Plato at PhilPapers

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- Plato

- 420s BC births

- 340s BC deaths

- 5th-century BC Greek philosophers

- 4th-century BC Greek philosophers

- Academic philosophers

- Ancient Athenian philosophers

- Ancient Greek epistemologists

- Ancient Greek ethicists

- Ancient Greek logicians

- Ancient Greek metaphysicians

- Ancient Greek philosophers of mind

- Ancient Greek physicists

- Ancient Greek political philosophers

- Ancient Greek philosophers of art

- Ancient Greek philosophers of language

- Ancient Syracuse

- Attic Greek writers

- Characters in the Divine Comedy

- Epigrammatists of the Greek Anthology

- Idealists

- Philosophers of education

- Pupils of Socrates

- Rationalists

- Rhetoric theorists