Bletchley Park

| Bletchley Park | |

|---|---|

The mansion in 2017 | |

| Type | Codebreaking centre and museum |

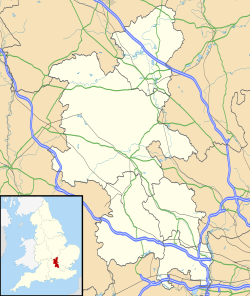

| Location | Bletchley, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Coordinates | 51°59′53″N 0°44′28″W / 51.99806°N 0.74111°W |

| Area | 58 acres |

| Built | 1877 (mansion), 1939–1945 (wartime buildings) |

| Original use | Government intelligence site |

| Current use | Bletchley Park Museum |

| Owner | Bletchley Park Trust |

| Website | bletchleypark |

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. During World War II, the estate housed the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), which regularly penetrated the secret communications of the Axis Powers – most importantly the German Enigma and Lorenz ciphers. The GC&CS team of codebreakers included John Tiltman, Dilwyn Knox, Alan Turing, Harry Golombek, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander, Donald Michie, Bill Tutte and Stuart Milner-Barry.

The team at Bletchley Park, 75% women, devised automatic machinery to help with decryption, culminating in the development of Colossus, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer.[a] Codebreaking operations at Bletchley Park ended in 1946 and all information about the wartime operations was classified until the mid-1970s. After the war it had various uses and now houses the Bletchley Park museum.

House and pre-war history

[edit]It was first known as Bletchley Park after its purchase in 1877 by the architect Samuel Lipscomb Seckham,[1] who built a house there.[2] The estate of 581 acres (235 ha) was bought in 1883 by Sir Herbert Samuel Leon, who expanded the house[3] into what architect Landis Gores called a "maudlin and monstrous pile",[4][5] combining Victorian Gothic, Tudor, and Dutch Baroque styles.[6] After the death of Herbert Leon in 1926, the estate continued to be occupied by his widow Fanny Leon (née Higham) until her death in 1937.[7] In 1938, the mansion and much of the site was bought by a builder for a housing estate, but in May 1938 Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, head of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS or MI6), bought the site for use in the event of war.[8]

World War II

[edit]Preparation for War

[edit]

Sinclair bought the mansion and 58 acres (23 ha) of land for use by Code and Cypher School and SIS. A key advantage seen by Sinclair and his colleagues (inspecting the site under the cover of "Captain Ridley's shooting party")[9] was Bletchley's geographical centrality. It was almost immediately adjacent to Bletchley railway station, where the "Varsity Line" between Oxford and Cambridge – whose universities were expected to supply many of the code-breakers – met the main West Coast railway line connecting London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh. Watling Street, the main road linking London to the north-west (subsequently the A5) was close by, and high-volume communication links were available at the telegraph and telephone repeater station in nearby Fenny Stratford.[10] Sinclair bought the park using £6,000 (£484,000 today) of his own money as the Government said they did not have the budget to do so.[11]

Five weeks before the outbreak of war, Warsaw's Cipher Bureau revealed its achievements in breaking Enigma to astonished French and British personnel.[12] The British used the Poles' information and techniques, and the Enigma clone sent to them in August 1939, which greatly increased their (previously very limited) success in decrypting Enigma messages.[13]

Early work

[edit]

The first personnel of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) moved to Bletchley Park on 15 August 1939. The Naval, Military, and Air Sections were on the ground floor of the mansion, together with a telephone exchange, teleprinter room, kitchen, and dining room; the top floor was allocated to MI6. Construction of the wooden huts began in late 1939, and Elmers School, a neighbouring boys' boarding school in a Victorian Gothic redbrick building by a church, was acquired for the Commercial and Diplomatic Sections.[15]

The only direct enemy damage to the site was done 20–21 November 1940 by three bombs probably intended for Bletchley railway station; Hut 4, shifted two feet off its foundation, was winched back into place as work inside continued.[16]

Action This Day

[edit]During a morale-boosting visit on 9 September 1941, Winston Churchill reportedly remarked to Denniston or Menzies: "I told you to leave no stone unturned to get staff, but I had no idea you had taken me so literally."[17] Six weeks later, having failed to get sufficient typing and unskilled staff to achieve the productivity that was possible, Turing, Welchman, Alexander and Milner-Barry wrote directly to Churchill. His response was "Action this day make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done."[18]

Allied involvement

[edit]After the United States joined World War II, a number of American cryptographers were posted to Hut 3, and from May 1943 onwards there was close co-operation between British and American intelligence[19] leading to the 1943 BRUSA Agreement which was the forerunner of the Five Eyes partnership.[20]

In contrast, the Soviet Union was never officially told of Bletchley Park and its activities, a reflection of Churchill's distrust of the Soviets even during the US-UK-USSR alliance imposed by the Nazi threat.[21] However Bletchley Park was infiltrated by the Soviet mole John Cairncross, a member of the Cambridge Spy Ring, who leaked Ultra material to Moscow.[22]

Personnel

[edit]

| The Enigma cipher machine |

|---|

| Enigma machine |

| Breaking Enigma |

| Related |

Admiral Hugh Sinclair was the founder and head of GC&CS between 1919 and 1938 with Commander Alastair Denniston being operational head of the organization from 1919 to 1942, beginning with its formation from the Admiralty's Room 40 (NID25) and the War Office's MI1b.[23] Key GC&CS cryptanalysts who moved from London to Bletchley Park included John Tiltman, Dillwyn "Dilly" Knox, Josh Cooper, Oliver Strachey and Nigel de Grey. These people had a variety of backgrounds – linguists and chess champions were common, and Knox's field was papyrology. The British War Office recruited top solvers of cryptic crossword puzzles, as these individuals had strong lateral thinking skills.[24]

On the day Britain declared war on Germany, Denniston wrote to the Foreign Office about recruiting "men of the professor type".[25] Personal networking drove early recruitments, particularly of men from the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. Trustworthy women were similarly recruited for administrative and clerical jobs.[26] In one 1941 recruiting stratagem, The Daily Telegraph was asked to organise a crossword competition, after which promising contestants were discreetly approached about "a particular type of work as a contribution to the war effort".[27]

Denniston recognised, however, that the enemy's use of electromechanical cipher machines meant that formally trained mathematicians would also be needed;[28] Oxford's Peter Twinn joined GC&CS in February 1939;[29] Cambridge's Alan Turing[30] and Gordon Welchman[31] began training in 1938 and reported to Bletchley the day after war was declared, along with John Jeffreys. Later-recruited cryptanalysts included the mathematicians Derek Taunt,[32] Jack Good, Bill Tutte,[33] and Max Newman; historian Harry Hinsley, and chess champions Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry.[34] Joan Clarke was one of the few women employed at Bletchley as a full-fledged cryptanalyst.[35][36]

When seeking to recruit more suitably advanced linguists, John Tiltman turned to Patrick Wilkinson of the Italian section for advice, and he suggested asking Lord Lindsay of Birker, of Balliol College, Oxford, S. W. Grose, and Martin Charlesworth, of St John's College, Cambridge, to recommend classical scholars or applicants to their colleges.[37]

This eclectic staff of "Boffins and Debs" (scientists and debutantes, young women of high society)[38] caused GC&CS to be whimsically dubbed the "Golf, Cheese and Chess Society".[39] Among those who worked there and later became famous in other fields were historian Asa Briggs, politician Roy Jenkins and novelist Angus Wilson.[40]

After initial training at the Inter-Service Special Intelligence School set up by John Tiltman (initially at an RAF depot in Buckingham and later in Bedford – where it was known locally as "the Spy School")[41] staff worked a six-day week, rotating through three shifts: 4 p.m. to midnight, midnight to 8 a.m. (the most disliked shift), and 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., each with a half-hour meal break. At the end of the third week, a worker went off at 8 a.m. and came back at 4 p.m., thus putting in 16 hours on that last day. The irregular hours affected workers' health and social life, as well as the routines of the nearby homes at which most staff lodged. The work was tedious and demanded intense concentration; staff got one week's leave four times a year, but some "girls" collapsed and required extended rest.[42] Recruitment took place to combat a shortage of experts in Morse code and German.[43]

In January 1945, at the peak of codebreaking efforts, 8,995 personnel were working at Bletchley and its outstations.[44] About three-quarters of these were women.[45] Many of the women came from middle-class backgrounds and held degrees in the areas of mathematics, physics and engineering; they were given the chance due to the lack of men, who had been sent to war. They performed calculations and coding and hence were integral to the computing processes.[46] Among them were Eleanor Ireland, who worked on the Colossus computers[47] and Ruth Briggs, a German scholar, who worked within the Naval Section.[48][49]

The female staff in Dilwyn Knox's section were sometimes termed "Dilly's Fillies".[50] Knox's methods enabled Mavis Lever (who married mathematician and fellow code-breaker Keith Batey) and Margaret Rock to solve a German code, the Abwehr cipher.[51][52]

Many of the women had backgrounds in languages, particularly French, German and Italian. Among them were Rozanne Colchester, a translator who worked mainly for the Italian air forces Section,[53] and Cicely Mayhew, recruited straight from university, who worked in Hut 8, translating decoded German Navy signals,[54] as did Jane Fawcett (née Hughes) who decrypted a vital message concerning the German battleship Bismarck and after the war became an opera singer and buildings conservationist.[40]

Alan Brooke (CIGS) in his secret wartime diary frequently refers to “intercepts”:[55]

- 16 April 1942: Took lunch in car and went to see the organization for breaking down ciphers [Bletchley Park] – a wonderful set of professors and genii! I marvel at the work they succeed in doing.

- 28 June 1945: After lunch (with Andrew Cunningham (RN) and Sinclair (RAF) we went to “The Park” … I began by addressing some 400 of the workers who consist of all 3 services, both sexes, and civilians, They come from every sort of walk of life, professors, students, actors, dancers, mathematicians, electricians signallers, etc. I thanked them on behalf of the Chiefs of Staff and congratulated them on the results of their work. We then toured round the establishment and had tea before returning.

Secrecy

[edit]Properly used, the German Enigma and Lorenz ciphers should have been virtually unbreakable, but flaws in German cryptographic procedures, and poor discipline among the personnel carrying them out, created vulnerabilities that made Bletchley's attacks just barely feasible. These vulnerabilities, however, could have been remedied by relatively simple improvements in enemy procedures,[12] and such changes would certainly have been implemented had Germany had any hint of Bletchley's success. Thus the intelligence Bletchley produced was considered wartime Britain's "Ultra secret" – higher even than the normally highest classification Most Secret – and security was paramount.[56]

All staff signed the Official Secrets Act (1939) and a 1942 security warning emphasised the importance of discretion even within Bletchley itself: "Do not talk at meals. Do not talk in the transport. Do not talk travelling. Do not talk in the billet. Do not talk by your own fireside. Be careful even in your Hut ..."[57]

Nevertheless, there were security leaks. Jock Colville, the Assistant Private Secretary to Winston Churchill, recorded in his diary on 31 July 1941, that the newspaper proprietor Lord Camrose had discovered Ultra and that security leaks "increase in number and seriousness".[58]

Despite the high degree of secrecy surrounding Bletchley Park during the Second World War, unique and hitherto unknown amateur film footage of the outstation at nearby Whaddon Hall came to light in 2020, after being anonymously donated to the Bletchley Park Trust.[59][60] A spokesman for the Trust noted the film's existence was all the more incredible because it was "very, very rare even to have [still] photographs" of the park and its associated sites.[61]

Bletchley Park was known as "B.P." to those who worked there.[62] "Station X" (X = Roman numeral ten), "London Signals Intelligence Centre", and "Government Communications Headquarters" were all cover names used during the war.[63] The formal posting of the many "Wrens" – members of the Women's Royal Naval Service – working there, was to HMS Pembroke V. Royal Air Force names of Bletchley Park and its outstations included RAF Eastcote, RAF Lime Grove and RAF Church Green.[64] The postal address that staff had to use was "Room 47, Foreign Office".[65]

Intelligence reporting

[edit]

Initially, when only a very limited amount of Enigma traffic was being read,[67] deciphered non-Naval Enigma messages were sent from Hut 6 to Hut 3 which handled their translation and onward transmission. Subsequently, under Group Captain Eric Jones, Hut 3 expanded to become the heart of Bletchley Park's intelligence effort, with input from decrypts of "Tunny" (Lorenz SZ42) traffic and many other sources. Early in 1942 it moved into Block D, but its functions were still referred to as Hut 3.[68]

Hut 3 contained a number of sections: Air Section "3A", Military Section "3M", a small Naval Section "3N", a multi-service Research Section "3G" and a large liaison section "3L".[69] It also housed the Traffic Analysis Section, SIXTA.[70] An important function that allowed the synthesis of raw messages into valuable Military intelligence was the indexing and cross-referencing of information in a number of different filing systems.[71] Intelligence reports were sent out to the Secret Intelligence Service, the intelligence chiefs in the relevant ministries, and later on to high-level commanders in the field.[72]

Naval Enigma deciphering was in Hut 8, with translation in Hut 4. Verbatim translations were sent to the Naval Intelligence Division (NID) of the Admiralty's Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC), supplemented by information from indexes as to the meaning of technical terms and cross-references from a knowledge store of German naval technology.[73] Where relevant to non-naval matters, they would also be passed to Hut 3. Hut 4 also decoded a manual system known as the dockyard cipher, which sometimes carried messages that were also sent on an Enigma network. Feeding these back to Hut 8 provided excellent "cribs" for Known-plaintext attacks on the daily naval Enigma key.[74]

Listening stations

[edit]Initially, a wireless room was established at Bletchley Park. It was set up in the mansion's water tower under the code name "Station X",[75] a term now sometimes applied to the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley as a whole. The "X" is the Roman numeral "ten", this being the Secret Intelligence Service's tenth such station. Due to the long radio aerials stretching from the wireless room, the radio station was moved from Bletchley Park to nearby Whaddon Hall to avoid drawing attention to the site.[76][77]

Subsequently, other listening stations – the Y-stations, such as the ones at Chicksands in Bedfordshire, Beaumanor Hall, Leicestershire (where the headquarters of the War Office "Y" Group was located) and Beeston Hill Y Station in Norfolk – gathered raw signals for processing at Bletchley. Coded messages were taken down by hand and sent to Bletchley on paper by motorcycle despatch riders or (later) by teleprinter.[78]

Additional buildings

[edit]The wartime needs required the building of additional accommodation.[79]

Huts

[edit]

Often a hut's number became so strongly associated with the work performed inside that even when the work was moved to another building it was still referred to by the original "Hut" designation.[80][81]

- Hut 1: The first hut, built in 1939[82] used to house the Wireless Station for a short time,[75] later administrative functions such as transport, typing, and Bombe maintenance. The first Bombe, "Victory", was initially housed here.[83]

- Hut 2: A recreational hut for "beer, tea, and relaxation".[84]

- Hut 3: Intelligence: translation and analysis of Army and Air Force decrypts[85]

- Hut 4: Naval intelligence: analysis of Naval Enigma and Hagelin decrypts[86]

- Hut 5: Military intelligence including Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese ciphers and German police codes.[87]

- Hut 6: Cryptanalysis of Army and Air Force Enigma[88]

- Hut 7: Cryptanalysis of Japanese naval codes and intelligence.[89][90]

- Hut 8: Cryptanalysis of Naval Enigma.[73]

- Hut 9: ISOS (Intelligence Section Oliver Strachey).

- Hut 10: Secret Intelligence Service (SIS or MI6) codes, Air and Meteorological sections.[91]

- Hut 11: Bombe building.[92]

- Hut 14: Communications centre.[93]

- Hut 15: SIXTA (Signals Intelligence and Traffic Analysis).

- Hut 16: ISK (Intelligence Service Knox) Abwehr ciphers.

- Hut 18: ISOS (Intelligence Section Oliver Strachey).

- Hut 23: Primarily used to house the engineering department. After February 1943, Hut 3 was renamed Hut 23.

Blocks

[edit]In addition to the wooden huts, there were a number of brick-built "blocks".

- Block A: Naval Intelligence.

- Block B: Italian Air and Naval, and Japanese code breaking.

- Block C: Stored the substantial punch-card indexes.

- Block D: From February 1943 it housed those from Hut 3, who synthesised intelligence from multiple sources, Huts 6 and 8 and SIXTA.[94]

- Block E: Incoming and outgoing Radio Transmission and TypeX.

- Block F: Included the Newmanry and Testery, and Japanese Military Air Section. It has since been demolished.

- Block G: Traffic analysis and deception operations.

- Block H: Tunny and Colossus (now The National Museum of Computing).

Work on specific countries' signals

[edit]German signals

[edit]Most German messages decrypted at Bletchley were produced by one or another version of the Enigma cipher machine, but an important minority were produced by the even more complicated twelve-rotor Lorenz SZ42 on-line teleprinter cipher machine used for high command messages, known as Fish.[95]

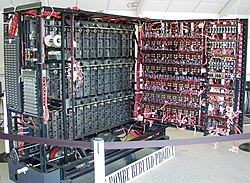

The bombe was an electromechanical device whose function was to discover some of the daily settings of the Enigma machines on the various German military networks.[97][98][99] Its pioneering design was developed by Alan Turing (with an important contribution from Gordon Welchman) and the machine was engineered by Harold 'Doc' Keen of the British Tabulating Machine Company. Each machine was about 7 feet (2.1 m) high and wide, 2 feet (0.61 m) deep and weighed about a ton.[100]

At its peak, GC&CS was reading approximately 4,000 messages per day.[101] As a hedge against enemy attack[102] most bombes were dispersed to installations at Adstock and Wavendon (both later supplanted by installations at Stanmore and Eastcote), and Gayhurst.[103][104]

Luftwaffe messages were the first to be read in quantity. The German navy had much tighter procedures, and the capture of code books was needed before they could be broken. When, in February 1942, the German navy introduced the four-rotor Enigma for communications with its Atlantic U-boats, this traffic became unreadable for a period of ten months.[105] Britain produced modified bombes, but it was the success of the US Navy Bombe that was the main source of reading messages from this version of Enigma for the rest of the war. Messages were sent to and fro across the Atlantic by enciphered teleprinter links.[78]

Bletchley's work was essential to defeating the U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic, and to the British naval victories in the Battle of Cape Matapan and the Battle of North Cape. In 1941, Ultra exerted a powerful effect on the North African desert campaign against German forces under General Erwin Rommel. General Sir Claude Auchinleck wrote that were it not for Ultra, "Rommel would have certainly got through to Cairo". While not changing the events, "Ultra" decrypts featured prominently in the story of Operation SALAM, László Almásy's mission across the desert behind Allied lines in 1942.[106] Prior to the Normandy landings on D-Day in June 1944, the Allies knew the locations of all but two of Germany's fifty-eight Western-front divisions.[107]

The Lorenz messages were codenamed Tunny at Bletchley Park. They were only sent in quantity from mid-1942. The Tunny networks were used for high-level messages between German High Command and field commanders. With the help of German operator errors, the cryptanalysts in the Testery (named after Ralph Tester, its head) worked out the logical structure of the machine despite not knowing its physical form. They devised automatic machinery to help with decryption, which culminated in Colossus, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer. This was designed and built by Tommy Flowers and his team at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill. The prototype first worked in December 1943, was delivered to Bletchley Park in January and first worked operationally on 5 February 1944. Enhancements were developed for the Mark 2 Colossus, the first of which was working at Bletchley Park on the morning of 1 June in time for D-day. Flowers then produced one Colossus a month for the rest of the war, making a total of ten with an eleventh part-built. The machines were operated mainly by Wrens in a section named the Newmanry after its head Max Newman.[108]

Italian signals

[edit]Italian signals had been of interest since Italy's attack on Abyssinia in 1935. During the Spanish Civil War the Italian Navy used the K model of the commercial Enigma without a plugboard; this was solved by Knox in 1937. When Italy entered the war in 1940 an improved version of the machine was used, though little traffic was sent by it and there were "wholesale changes" in Italian codes and cyphers.[109]

Knox was given a new section for work on Enigma variations, which he staffed with women ("Dilly's girls"), who included Margaret Rock, Jean Perrin, Clare Harding, Rachel Ronald, Elisabeth Granger; and Mavis Lever.[110] Mavis Lever solved the signals revealing the Italian Navy's operational plans before the Battle of Cape Matapan in 1941, leading to a British victory.[111]

Although most Bletchley staff did not know the results of their work, Admiral Cunningham visited Bletchley in person a few weeks later to congratulate them.[111]

On entering World War II in June 1940, the Italians were using book codes for most of their military messages. The exception was the Italian Navy, which after the Battle of Cape Matapan started using the C-38 version of the Boris Hagelin rotor-based cipher machine, particularly to route their navy and merchant marine convoys to the conflict in North Africa.[112] As a consequence, JRM Butler recruited his former student Bernard Willson to join a team with two others in Hut 4.[86][113] In June 1941, Willson became the first of the team to decode the Hagelin system, thus enabling military commanders to direct the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force to sink enemy ships carrying supplies from Europe to Rommel's Afrika Korps. This led to increased shipping losses and, from reading the intercepted traffic, the team learnt that between May and September 1941 the stock of fuel for the Luftwaffe in North Africa reduced by 90 per cent.[114] After an intensive language course, in March 1944 Willson switched to Japanese language-based codes.[115]

A Middle East Intelligence Centre (MEIC) was set up in Cairo in 1939. When Italy entered the war in June 1940, delays in forwarding intercepts to Bletchley via congested radio links resulted in cryptanalysts being sent to Cairo. A Combined Bureau Middle East (CBME) was set up in November, though the Middle East authorities made "increasingly bitter complaints" that GC&CS was giving too little priority to work on Italian cyphers. However, the principle of concentrating high-grade cryptanalysis at Bletchley was maintained.[116] John Chadwick started cryptanalysis work in 1942 on Italian signals at the naval base 'HMS Nile' in Alexandria. Later, he was with GC&CS; in the Heliopolis Museum, Cairo and then in the Villa Laurens, Alexandria.[117]

Soviet signals

[edit]Soviet signals had been studied since the 1920s. In 1939–40, John Tiltman (who had worked on Russian Army traffic from 1930) set up two Russian sections at Wavendon (a country house near Bletchley) and at Sarafand in Palestine. Two Russian high-grade army and navy systems were broken early in 1940. Tiltman spent two weeks in Finland, where he obtained Russian traffic from Finland and Estonia in exchange for radio equipment. In June 1941, when the Soviet Union became an ally, Churchill ordered a halt to intelligence operations against it. In December 1941, the Russian section was closed down, but in late summer 1943 or late 1944, a small GC&CS Russian cypher section was set up in London overlooking Park Lane, then in Sloane Square.[118]

Japanese signals

[edit]An outpost of the Government Code and Cypher School had been set up in Hong Kong in 1935, the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB). The FECB naval staff moved in 1940 to Singapore, then Colombo, Ceylon, then Kilindini, Mombasa, Kenya. They succeeded in deciphering Japanese codes with a mixture of skill and good fortune.[119] The Army and Air Force staff went from Singapore to the Wireless Experimental Centre at Delhi, India.[120]

In early 1942, a six-month crash course in Japanese, for 20 undergraduates from Oxford and Cambridge, was started by the Inter-Services Special Intelligence School in Bedford, in a building across from the main Post Office. This course was repeated every six months until war's end. Most of those completing these courses worked on decoding Japanese naval messages in Hut 7, under John Tiltman.[120]

By mid-1945, well over 100 personnel were involved with this operation, which co-operated closely with the FECB and the US Signal intelligence Service at Arlington Hall, Virginia. In 1999, Michael Smith wrote that: "Only now are the British codebreakers (like John Tiltman, Hugh Foss, and Eric Nave) beginning to receive the recognition they deserve for breaking Japanese codes and cyphers".[121]

Post-war uses and legacy

[edit]The Government Code & Cypher School became the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), moving to Eastcote in 1946 and to Cheltenham in 1951.[122]

Continued secrecy and official recognition

[edit]

Until the mid 1970s the thirty year rule meant that there was no official mention of the work done at Bletchley Park. This meant that there were many operations where codes broken by Bletchley Park played an important role, but this was not present in the history of those events.[123]

After the War, the secrecy imposed on Bletchley staff remained in force, so that most relatives never knew more than that a child, spouse, or parent had done some kind of secret war work.[124] Churchill referred to the Bletchley staff as "the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled".[125] That said, occasional mentions of the work performed at Bletchley Park slipped the censor's net and appeared in print.[126]

With the publication of F. W. Winterbotham's The Ultra Secret in 1974[127][b] public discussion of Bletchley Park's work in the English speaking world finally became accepted, although some former staff considered themselves bound to silence forever.[128] Winterbotham's book was written from memory and although officially allowed, there was no access to archives.[129]

Not until July 2009 did the British government fully acknowledge the contribution of the many people working at Bletchley Park.[130] Only then was a commemorative medal struck to be presented to those involved.[131] The gilded medal bears the inscription GC&CS 1939–1945 Bletchley Park and its Outstations.[132]

Decline and partial demolition

[edit]The site passed through a succession of hands and saw a number of uses, including as a teacher-training college, and by various government agencies, including the GPO and the Civil Aviation Authority. One large building, block F, was demolished in 1987 by which time the site was being run down with tenants leaving.[133]

Bletchley Park museums

[edit]

Bletchley Park Trust was set up in 1991 by a group of people who recognised the site's importance,[134] as it was at risk of being sold off for housing.[135] and in February 1992, the Milton Keynes Borough Council declared most of the Park a conservation area.[136]

The site opened to visitors in 1993, and was formally inaugurated by the Duke of Kent as Chief Patron in July 1994[137] and Tony Sale became the first director of the Bletchley Park Museums in 1994.[138]

In 1999 the land owners, the Property Advisors to the Civil Estate and BT Group, granted a lease to the Trust giving it control over most of the site.[139]

June 2014 saw the completion of an £8 million restoration project by museum design specialist, Event Communications, which was marked by a visit from Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge.[140] The Duchess' paternal grandmother, Valerie Middleton, and Valerie's twin sister, Mary (née Glassborow), both worked at Bletchley Park during the war. The twin sisters worked as Foreign Office Civilians in Hut 6, where they managed the interception of enemy and neutral diplomatic signals for decryption. Valerie married Catherine's grandfather, Captain Peter Middleton.[141][142][143] A memorial at Bletchley Park commemorates Mary and Valerie Middleton's work as code-breakers.[144]

The Bletchley Park Learning Department offers educational group visits with active learning activities for schools and universities. Visits can be booked in advance during term time, where students can engage with the history of Bletchley Park and understand its wider relevance for computer history and national security. Their workshops cover introductions to codebreaking, cyber security and the story of Enigma and Lorenz.[145]

Funding

[edit]In October 2005, American billionaire Sidney Frank donated £500,000 to Bletchley Park Trust to fund a new Science Centre dedicated to Alan Turing.[146] Simon Greenish joined as Director in 2006 to lead the fund-raising effort[147] in a post he held until 2012 when Iain Standen took over the leadership role.[148] In July 2008, a letter to The Times from more than a hundred academics condemned the neglect of the site.[149][150] In September 2008, PGP, IBM and other technology firms announced a fund-raising campaign to repair the facility.[151] On 6 November 2008 it was announced that English Heritage would donate £300,000 to help maintain the buildings at Bletchley Park, and that they were in discussions regarding the donation of a further £600,000.[152]

In October 2011, the Bletchley Park Trust received a £4.6 million Heritage Lottery Fund grant to be used "to complete the restoration of the site, and to tell its story to the highest modern standards" on the condition that £1.7 million of match funding is raised by the Bletchley Park Trust.[153][154] Just weeks later, Google contributed £550,000[155] and by June 2012 the trust had successfully raised £2.4 million to unlock the grants to restore Huts 3 and 6, as well as develop its exhibition centre in Block C.[156]

Additional income is raised by renting Block H to the National Museum of Computing, and some office space in various parts of the park to private firms.[157][158][159]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic the Trust expected to lose more than £2 million in 2020 and be required to cut a third of its workforce. Former MP John Leech asked Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft to donate £400,000 each to secure the future of the Trust. Leech had led the successful campaign to pardon Alan Turing and implement Turing's Law.[160]

Other organisations sharing the campus

[edit]The National Museum of Computing

[edit]

The National Museum of Computing is housed in Block H, which is rented from the Bletchley Park Trust. Its Colossus and Tunny galleries tell an important part of allied breaking of German codes during World War II. There is a working reconstruction of a Bombe and a rebuilt Colossus computer which was used on the high-level Lorenz cipher, codenamed Tunny by the British.[162][163]

The museum, which opened in 2007, is an independent voluntary organisation that is governed by its own board of trustees. Its aim is "To collect and restore computer systems particularly those developed in Britain and to enable people to explore that collection for inspiration, learning and enjoyment."[164] Through its many exhibits, the museum displays the story of computing through the mainframes of the 1960s and 1970s, and the rise of personal computing in the 1980s. It has a policy of having as many of the exhibits as possible in full working order.[165]

Science and Innovation Centre

[edit]This consisted of serviced office accommodation housed in Bletchley Park's Blocks A and E, and the upper floors of the Mansion. Its aim was to foster the growth and development of dynamic knowledge-based start-ups and other businesses.[166] It closed in 2021 and blocks A and E were taken into use as part of the museum.[167]

Proposed National College of Cyber Security

[edit]In April 2020 Bletchley Park Capital Partners, a private company run by Tim Reynolds, Deputy Chairman of the National Museum of Computing, announced plans to sell off the freehold to part of the site containing former Block G for commercial development. Offers of between £4 million and £6 million were reportedly being sought for the 3 acre plot, for which planning permission for employment purposes was granted in 2005.[168][169] Previously, the construction of a National College of Cyber Security for students aged from 16 to 19 years old had been envisaged on the site, to be housed in Block G after renovation with funds supplied by the Bletchley Park Science and Innovation Centre.[170][171][172][173]

RSGB National Radio Centre

[edit]The Radio Society of Great Britain's National Radio Centre (including a library, radio station, museum and bookshop) are in a newly constructed building close to the main Bletchley Park entrance.[174][175]

In popular culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]- Bletchley featured heavily in Robert Harris' novel Enigma (1995).[176]

- A fictionalised version of Bletchley Park is featured in Neal Stephenson's novel Cryptonomicon (1999).[177]

- Bletchley Park plays a significant role in Connie Willis' novel All Clear (2010).[178]

- The Agatha Christie novel N or M?, published in 1941, was about spies during the Second World War and featured a character called Major Bletchley. Christie was friends with one of the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, and MI5 thought that the character name might have been a joke indicating that she knew what was happening there. It turned out to be a coincidence.[179][180]

- Bletchley Park is the setting of Kate Quinn's 2021 historical fiction novel, The Rose Code. Quinn used the likenesses of true veterans of Bletchley Park as inspiration for her story of three women who worked in some of the different areas at Bletchley Park.[181][182]

Film

[edit]

- The film Enigma (2001), which was based upon Robert Harris's book and starred Kate Winslet, Saffron Burrows and Dougray Scott, is set in part in Bletchley Park.[183]

- The film The Imitation Game (2014), starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing, is set in Bletchley Park, and was partially filmed there.[184]

Radio

[edit]- The radio show Hut 33 is a situation comedy set in the fictional 33rd Hut of Bletchley Park.[185]

- The Big Finish Productions Doctor Who audio Criss-Cross, released in September 2015, features the Sixth Doctor working undercover in Bletchley Park to decode a series of strange alien signals that have hindered his TARDIS, the audio also depicting his first meeting with his new companion Constance Clarke.[186]

- The Bletchley Park Podcast began in August 2012, with new episodes being released approximately monthly. It features stories told by the codebreakers, staff and volunteers, audio from events and reports on the development of Bletchley Park.[187]

Television

[edit]- The 1979 ITV television serial Danger UXB features the character Steven Mount, a codebreaker at Bletchley who is driven to a nervous breakdown (and eventual suicide) by the stressful and repetitive nature of the work.[188]

- In the TV series Foyle's War, Adam Wainwright (Samantha Stewart's fiancé, then husband) is a former Bletchley Park codebreaker.[189][190]

- The Second World War code-breaking sitcom pilot "Satsuma & Pumpkin" was recorded at Bletchley Park in 2003 and featured Bob Monkhouse in his last screen role. The BBC declined to produce the show and develop it further before creating effectively the same show on Radio 4 several years later, featuring some of the same cast, entitled Hut 33.[191][192]

- Bletchley came to wider public attention with the documentary series Station X (1999).[193]

- The 2012 ITV programme The Bletchley Circle is a set of murder mysteries set in 1952 and 1953. The protagonists are four female former Bletchley codebreakers, who use their skills to solve crimes. The pilot episode's opening scene was filmed on-site, and the set was asked to remain there for its close adaptation of the historic setting.[194][195]

- The 2018 programme The Bletchley Circle: San Francisco is a spin-off of The Bletchley Circle. It takes place in San Francisco and features two characters from the original series.[196]

- Ian McEwan's television play The Imitation Game (1980) concludes at Bletchley Park.[197]

- Bletchley Park was featured in the sixth and final episode of the BBC TV documentary The Secret War (1977), presented and narrated by William Woodard. This episode featured interviews with Gordon Welchman, Harry Golombek, Peter Calvocoressi, F. W. Winterbotham, Max Newman, Jack Good, and Tommy Flowers.[198]

- The Agent Carter season 2 episode "Smoke & Mirrors" reveals that Agent Peggy Carter worked at Bletchley Park early in the war before joining the Strategic Scientific Reserve.[199]

Theatre

[edit]- The play Breaking the Code (1986) is set at Bletchley Park.[200]

Exhibitions

[edit]- A 2012 London Science Museum exhibit, "Code Breaker: Alan Turing's Life and Legacy", marking the centenary of his birth, included a short film of statements by half a dozen participants and historians of the World War II Bletchley Park Ultra operations.[201]

See also

[edit]- Arlington Hall – Historic building in Virginia

- Beeston Hill Y Station – Secret listening station located on Beeston Hill, Sheringham

- Far East Combined Bureau – UK intelligence outstation in Hong Kong prewar, then Singapore, Colombo (Ceylon) and Kilindini (Kenya)

- List of people associated with Bletchley Park

- List of women in Bletchley Park

- OP-20-G – WWII US Navy signals intelligence group, based in Washington, D.C.

- RAF Medmenham – Former RAF base in Buckinghamshire, England

- Wireless Experimental Centre operated by the Intelligence Corps outside Delhi

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Colossus itself was designed and built by Tommy Flowers at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in north London, to solve a problem posed by mathematician Max Newman at the GC&CS. From there, it (and nine more) were installed and operated in Bletchley.

- ^ He had permission to publish, but no access to official records, so had to rely on memory.

References

[edit]- ^ Morrison, p. 89

- ^ "Bletchley Park House". www.heritagegateway.org.uk. Heritage Gateway. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Edward, Legg (1999), "Early History of Bletchley Park 1235–1937", Bletchley Park Trust Historic Guides, no. 1

- ^ Morrison, p. 81

- ^ McKay 2010, p. 34

- ^ "Bletchley Park – The House That Helped Save Britain in World War II – Where Enigma Was Decoded". Great British Houses. 14 November 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Bletchley Park before the War Archived 8 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Milton Keynes Heritage Association. Retrieved 2 October 2020

- ^ Morrison, pp. 102–103

- ^ McKay 2010, p. 11

- ^ "Fenny Stratford Telephone Repeater Station. Erection. A. Cole Ltd". National Archives. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Morrison, pp. 102–103

- ^ a b Milner-Barry 1993, p. 92

- ^ Twinn 1993, p. 127

- ^ Sale, Tony, Information flow from German ciphers to Intelligence to Allied commanders., archived from the original on 27 September 2011, retrieved 30 June 2011

- ^ Smith 1999, pp. 2–3

- ^ Bletchley Park National Codes Centre, The Cafe in Hut 4, archived from the original on 19 January 2013, retrieved 3 April 2011

- ^ Kahn1991, p. 185

- ^ Copeland 2004, p. 336

- ^ Taylor 1993, pp. 71, 72

- ^ Corera, Gordon (5 March 2021). "Diary reveals birth of secret UK-US spy pact that grew into Five Eyes". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J. (2010). The Concise Encyclopedia of World War II. Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0313330506.

- ^ Smith 2015, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Erskine & Smith 2011, p. 14

- ^ "Could you have been a codebreaker at Bletchley Park?". The Daily Telegraph. 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Budiansky 2000, p. 112

- ^ Hill 2004, pp. 13–23

- ^ McKay, Sinclair (26 August 2010), "Telegraph crossword: Cracking hobby won the day – The boffins of Bletchley cut their teeth on the Telegraph crossword", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 27 December 2014, retrieved 3 April 2018

- ^ Briggs 2011, pp. 3–4

- ^ Twinn 1993, p. 125

- ^ Hodges, Andrew (1992), Alan Turing: The Enigma, London: Vintage, p. 148, ISBN 978-0099116417

- ^ Welchman 1997, p. 11

- ^ Taunt, Derek, Hut 6: 1941-1945, p. 101 in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 100–112

- ^ Tutte, William T. (2006), My Work at Bletchley Park Appendix 4 in Copeland 2006, pp. 352–9

- ^ Grey 2012, p. 133

- ^ Burman, Annie. "Gendering decryption – decrypting gender The gender discourse of labour at Bletchley Park 1939–1945" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ "Women Codebreakers". Bletchley Park Research. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Richard Langhorne, Diplomacy and Intelligence During the Second World War (2004), p. 37

- ^ Hill 2004, pp. 62–71

- ^ BBC News UK: Saving Bletchley for the nation, 2 June 1999, archived from the original on 11 January 2007, retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ a b McKay, Sinclair (2021). 100 People you never knew were at Bletchley Park. London: Safe Haven. ISBN 9781838405120.

- ^ Smith 1999, pp. 79, 82

- ^ McKay 2010, pp. 70, 102, 105

- ^ "Last Surviving Bletchley Park 'Listener' Dies Aged 97". Forces network. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Agar 2003, p. 203.

- ^ "Women Codebreakers". Bletchley Park Research. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Light, Jennifer S. (1999). "Project MUSE - When Computers Were Women". Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 455–483. doi:10.1353/tech.1999.0128. S2CID 108407884. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Copeland, B. Jack; Bowen, Jonathan P.; Wilson, Robin; Sprevak, Mark (2017). "We were the world's first computer operators". The Turing Guide. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Hinsley, Francis Harry (1 January 2001). Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192801326.

- ^ "Women Codebreakers". Bletchley Park Research. 3 October 2013. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ McKay 2010, p. 14

- ^ Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh (2004). Enigma – The battle for the code. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. p. 129. ISBN 0-304-36662-5.

- ^ "The Abwehr Enigma Machine" (PDF). Bletchleypark.org.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Record Detail - Bletchley Park - Roll of Honour". Rollofhonour.bletchleypark.org.uk. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Lady Mayhew". The Times. 21 July 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Alanbrooke 2001, pp. 250, 700.

- ^ Hinsley & Stripp 1993, p. vii

- ^ Hill 2004, pp. 128–29

- ^ Colville 1985, p. 422.

- ^ "WW2 Codebreakers: Original Footage of MI6 staff at Whaddon Hall - The Hidden Film". 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ Brown, Mark (3 April 2020). "Silent film reel shows staff connected to Bletchley Park for first time". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "MI6: World War Two workers in rare 'forbidden' footage". BBC. 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Briggs 2011, p. 1

- ^ Aldrich 2010, p. 69

- ^ Shearer, Caroline (2014), My years at Bletchley Park – Station X, archived from the original on 26 February 2017, retrieved 27 January 2017

- ^ Good, Jack, Enigma and Fish, p. 154 in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 149–166

- ^ Bennett 1999, p. 302

- ^ Hinsley, F.H. (1993), Introduction: The influence of Ultra in the Second World War in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, p. 2

- ^ Kenyon 2019, p. 75.

- ^ Kenyon 2019, pp. 78, 81, 83.

- ^ Kenyon 2019, p. 70.

- ^ Nelson, Eric L. (September 2018), "The peripheral and central indexes at Bletchley Park during the Second World War", The Indexer, 36 (3): 95–101, doi:10.3828/indexer.2018.43, S2CID 165441349

- ^ Calvocoressi 2001, pp. 70–81

- ^ a b Calvocoressi 2001, p. 29

- ^ Erskine 2011, p. 170

- ^ a b Watson 1993, p. 307

- ^ Smith & Butters 2007, p. 10

- ^ Pidgeon 2003

- ^ a b "Teleprinter Building, Bletchley Park". Pastscape. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Watson, Bob, Appendix: How the Bletchley Park buildings took shape, pp. 306–310 in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 149–166

- ^ Some of this information has been derived from The Bletchley Park Trust's Roll of Honour Archived 18 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Smith & Butters 2007

- ^ "Bletchley Park - Virtual Tour". Codesandciphers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Sale, Tony, Virtual Wartime Bletchley Park: Alan Turing, the Enigma and the Bombe, archived from the original on 9 July 2011, retrieved 7 July 2011

- ^ McKay 2010, p. 52

- ^ Millward 1993, p. 17

- ^ a b Dakin 1993, p. 50

- ^ Seventy Years Ago This Month at Bletchley Park: July 1941, archived from the original on 20 July 2011, retrieved 8 July 2011

- ^ Welchman 1997

- ^ Loewe 1993, p. 260

- ^ Scott 1997

- ^ Kahn 1991, pp. 189–90

- ^ "Bletchley Park - Virtual Tour". Codesandciphers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Beaumanor & Garats Hay Amateur Radio Society "The operational huts"". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^ Kenyon 2019, p. 22.

- ^ "Virtual Lorenz revealed in tribute to wartime codebreakers at Bletchley Park". Total MK. 19 May 2017. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "The British Bombe". John Harper. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2005.

- ^ Budiansky 2000, p. 195

- ^ Sebag-Montefiore 2004, p. 375

- ^ Carter, Frank (2004), From Bombe Stops to Enigma Keys (PDF), Bletchley Park Codes Centre, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2010, retrieved 31 March 2010

- ^ Ellsbury, Graham (1988), "2. Description of the Bombe", The Turing Bombe: What it was and how it worked, archived from the original on 1 January 2011, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ Carter, Frank, "The Turing Bombe", The Rutherford Journal, ISSN 1177-1380, archived from the original on 27 July 2011, retrieved 26 June 2011

- ^ "Outstations from the Park", Bletchley Park Jewels, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 16 April 2010

- ^ Toms, Susan (2005), Enigma and the Eastcote connection, archived from the original on 4 December 2008, retrieved 16 April 2010

- ^ Welchman 1997, p. 141

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 34

- ^ Gross, Kuno, Michael Rolke and András Zboray, Operation SALAM Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine - László Almásy's most daring Mission in the Desert War, Belleville, München, 2013

- ^ Hinsley & Stripp 1993, p. 9

- ^ Good, Michie & Timms 1945, p. 276

- ^ Smith, Michael (2011). The Bletchley Park Codebreakers. Biteback. ISBN 978-1849540780.

- ^ Grey 2012, pp. 1323–3

- ^ a b Batey, Mavis (2011), Breaking Italian Naval Enigma, p. 81 in Erskine & Smith 2011, pp. 79–92

- ^ Hinsley 1996

- ^ Wilkinson, Patrick (1993), Italian naval ciphers in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 61–67

- ^ "July 1941". Bletchley Park. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ [permanent dead link]

- ^ Hinsley, Harry British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume One: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations (1979, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London) pp. 191–221, 570–72 ISBN 0 11 630933 4

- ^ "Life of John Chadwick : 1920 - 1998 : Classical Philologist, Lexicographer and Co-decipherer of Linear B" Archived 17 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Faculty of Classics, Cambridge University

- ^ Smith, Michael (2011), The Government Code and Cypher School and the First Cold War, pp. 13–34 in Erskine & Smith 2011

- ^ Smith, Michael. "Mombasa was base for high-level UK espionage operation". coastweek.com. Coastweek. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ a b Smith 2000, pp. 54–55, 175–180

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 127–51

- ^ GCHQ (2016), Bletchley Park - post-war, archived from the original on 13 October 2018, retrieved 12 October 2018

- ^ Summers, Deborah (29 January 2009). "30-year rule on government disclosure should be halved, Dacre inquiry says". The Guardian.

- ^ Hill 2004, pp. 129–35

- ^ Lewin 2001, p. 64

- ^ Thirsk 2008, pp. 61–68

- ^ Winterbotham, F. W. (1974). The Ultra Secret. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ^ Withers-Green, Sheila (2010), audiopause audio: I made a promise that I wouldn't say anything, archived from the original on 8 October 2011, retrieved 15 July 2011

- ^ Deutsch 1977, p. 17.

- ^ "The extraordinary female codebreakers of Bletchley Park". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Enigma codebreakers to be honoured finally". The Daily Telegraph. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Bletchley Park commemorative badge". GCHQ. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Block F, Bletchley Park". Pastscape. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Enever 1999.

- ^ The initial trustees included Roger Bristow, Ted Enever, Peter Wescombe and Dr Peter Jarvis of the Bletchley Archaeological & Historical Society. "Founding volunteers reflect on the battle to save Bletchley Park". Business MK. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ "Conservation areas in Milton Keynes". Milton Keynes Borough Council. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Computer Resurrection" (PDF). Computer Conservation Society. 1995. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2025. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ Anon (2014), "Peter Wescombe - obituary", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 13 October 2018, retrieved 12 October 2018

- ^ Bletchley Park Trust. "Bletchley Park History". Bletchleypark.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Bletchley Park Becomes A World-Class Museum and Visitor Centre". Museums+Heritage. 25 July 2014. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "Valerie Glassborow, Bletchley Park Veteran and Grandmother of HRH The Duchess of Cambridge". BletchleyPark.org.uk. 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Code me, Kate: British royal opens museum at restored WWII deciphering center, Bletchley Park". Fox News. 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Duchess of Cambridge opens Bletchley Park restored centre". BBC News. 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Furness, H (14 May 2019). "Kate meets the codebreakers: Duchess of Cambridge tells of her sadness over her grandmother's secret Bletchley Park life". UK Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

The 37-year-old opened up as she visited the estate near Milton Keynes on Tuesday to see a new exhibition celebrating the role codebreakers played in the D-Day landings almost 75 years ago....she was shown a memorial containing the name of her father's mother and great-aunt, who also worked at Bletchley.

- ^ "Bletchley Park". Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ Action This Day Archived 20 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Bletchley Park News, 28 February 2006

- ^ Greenish, Simon; Bowen, Jonathan; Copeland, Jack (2017). "Chapter 19 – Turing's monument". In Copeland, Jack; et al. (eds.). The Turing Guide. pp. 189–196.

- ^ Gorman, Jason (16 January 2012). "New Bletchley Park CEO, And A Tribute To Simon Greenish". codemanship.co.uk. UK: codemanship. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Saving the heritage of Bletchley Park (Letter)", The Times, archived from the original on 9 August 2011, retrieved 26 July 2008

- ^ "Neglect of Bletchley condemned" Archived 30 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News.

- ^ Espiner, Tom (8 September 2008). "PGP, IBM help Bletchley Park raise funds". CNET. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "New lifeline for Bletchley Park" Archived 6 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News.

- ^ "Bletchley Park wins #pound;4.6m Heritage Lottery Fund grant", BBC News, 5 October 2011, archived from the original on 20 July 2016, retrieved 21 June 2018

- ^ It's Happening!: The Long-Awaited Restoration of Historic Bletchley Park, Bletchley Park Trust, archived from the original on 4 November 2013, retrieved 7 April 2014

- ^ "Google gives £550k to Bletchley Park", The Register, archived from the original on 10 August 2017, retrieved 10 August 2017

- ^ "Bletchley Park gets £7.4m to tart up WWII code-breaking huts". The Register. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "BPSIC: Bletchley Park Science and Innovation Centre", Bpsic.com, archived from the original on 22 January 2013, retrieved 30 January 2013

- ^ "Bletchley Park Science and Innovation Centre". Bletchleypark.org. Bletchley Park Trust. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ "Bletchley Park Science and Innovation Centre". Bpsic.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Tech giants urged to help save cash-strapped Bletchley Park to preserve Alan Turing legacy". inews.co.uk. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Harper, John (2008), Bombe Rebuild Project, archived from the original on 4 December 2013, retrieved 24 March 2011

- ^ "Colossus Rebuild - Tony Sale". Codesandciphers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Rise of the machines, south of Milton Keynes". The Register. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Mission Statement of The National Museum of Computing, CodesandCiphers Heritage Trust, archived from the original on 14 February 2014, retrieved 8 April 2014

- ^ "Restoration". National Museum of Computing. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "CRS man swaps recruitment for cloud services". Channel Web. 4 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Historic buildings at the heart of the World War Two site now open". Bletchley Park. 23 October 2023. Archived from the original on 19 September 2024. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Historic Block G at Bletchley Park is being sold off for up to £6m in Milton Keynes". Milton Keynes Citizen. 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, Louisa (11 April 2020). "Bletchley Park's wartime buildings up for sale". The Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "National Museum of Computing involved in setting up cyber security college". Museums Association. 30 November 2016. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Ross, Eleanor. "School for teenage codebreakers to open in Bletchley Park | Technology". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "UK's first National College of Cyber Security to open at historic Bletchley Park". International Business Times. 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Tom (25 November 2016). "Cyber college for wannabe codebreakers planned at UK's iconic Bletchley Park". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "National Radio Centre Official Opening", RadCom, 88 (8), Radio Society of Great Britain: 12, August 2012

- ^ David Summer (October 2012). "RSGB opens showcase for amateur radio at Bletchley Park". QST. 96 (10). (Call Sign K1ZZ). The American Radio Relay League: 96.

- ^ "An Enigma Wrapped in a Mystery". The New York Times. 1995. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Neal Stephenson: Cryptomancer". Locus. 1 August 1999. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "The troubles with time travel in Connie Willis' All Clear". Gizmodo. 10 December 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (4 February 2013), "Agatha Christie was investigated by MI5 over Bletchley Park mystery", The Guardian, archived from the original on 23 September 2017, retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ "Agatha Christie was investigated by MI5 over Bletchley Park mystery". The Guardian. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Quinn, Kate (2021). The Rose Code. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0062943477. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ White, Peter (31 March 2021). "Bletchley Park Code Breaker Novel 'The Rose Code' By Kate Quinn Being Adapted For TV By Black Bear Pictures". Deadline. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Enigma". IMDb. 7 June 2002. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "The Imitation Game". IMDb. 25 December 2014. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Hut 33". BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Criss-Cross". Big Finish. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Bletchley Park". Audioboom. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Review: Danger UXB - The Heroic Story of the WWII Bomb Disposal Teams". Daily Express. 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Honeysuckle Weeks describes life on the Foyle's War set". foyleswar.com. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ "Bios: Adam Wainwright". foyleswar.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Comedy – Hut 33". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ Youngs, Ian (19 March 2004). "Bob Monkhouse's last laugh". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park". British Universities Film and Video Council. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Hollingshead, Iain (4 September 2012). "What happened to the women of Bletchley Park?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Shaw, Malcolm (6 September 2012). "Bletchley Park drama to air on television". ITV. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ White, Peter (4 June 2018). "'The Bletchley Circle: San Francisco': BritBox Offers First Glimpse Of Its First Original, Set To Launch In July". Deadline. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "The Imitation Game". TV Cream. 23 June 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Secret War (1977 BBC WW2 documentary)". Archive Television Musings. 14 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Marvel's Agent Carter: Peggy's Past Is (Finally!) Revealed". TV Line. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Henry, William A. III (23 November 1987), "Ingenuousness And Genius: Breaking The Code", Time, archived from the original on 22 October 2010, retrieved 10 May 2008

- ^ "'Codebreaker – Alan Turing's life and legacy' at the Science Museum – video". The Guardian.

Bibliography

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Agar, Jon (2003). The Government Machine: A Revolutionary History of the Computer (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2025.

- Alanbrooke, Field Marshal Lord (2001). War Diaries 1939–1945. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-526-5.

- Aldrich, Richard J. (2010), GCHQ: The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-727847-3

- Bennett, Ralph (1999) [1994], Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the war with Germany, 1939–1945 (New and Enlarged ed.), London: Random House, ISBN 978-0-7126-6521-6

- Briggs, Asa (2011), Secret Days: Code-breaking in Bletchley Park, Barnsley, England: Frontline Books, ISBN 978-1-84832-615-6

- Budiansky, Stephen (2000), Battle of wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II, Free Press, ISBN 978-0-684-85932-3

- Calvocoressi, Peter (2001) [1980], Top Secret Ultra, Cleobury Mortimer, Shropshire: M & M Baldwin, ISBN 0-947712-41-0

- Colville, John (1985). Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries, 1939-1945. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 422.

- Copeland, Jack (2004), Copeland, B. Jack (ed.), The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma, Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-825080-0

- Copeland, B. Jack, ed. (2006), Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4

- Dakin, Alec (1993), The Z Watch in Hut 4, Part I in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 50–56

- Deutsch, Harold C. (1977). "The Historical Impact of Revealing the Ultra Secret". Parameters. 7 (1): 16–32. doi:10.55540/0031-1723.1102. Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- Enever, Ted (1999), Britain's Best Kept Secret: Ultra's Base at Bletchley Park (3rd ed.), Sutton, ISBN 978-0-7509-2355-2

- Erskine, Ralph; Smith, Michael, eds. (2011), The Bletchley Park Codebreakers, Biteback Publishing Ltd, ISBN 978-1-84954-078-0 Updated and extended version of Action This Day: From Breaking of the Enigma Code to the Birth of the Modern Computer Bantam Press 2001

- Erskine, Ralph (2011), Breaking German Naval Enigma on Both Sides of the Atlantic in Erskine & Smith 2011, pp. 165–83

- Good, Jack; Michie, Donald; Timms, Geoffrey (1945), General Report on Tunny: With Emphasis on Statistical Methods, UK Public Record Office HW 25/4 and HW 25/5, archived from the original on 17 September 2010, retrieved 15 September 2010 That version is a facsimile copy, but there is a transcript of much of this document in '.pdf' format at: Sale, Tony (2001), Part of the 'General Report on Tunny', the Newmanry History, formatted by Tony Sale (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2005, retrieved 20 September 2010, and a web transcript of Part 1 at: Ellsbury, Graham, General Report on Tunny With Emphasis on Statistical Methods, archived from the original on 20 October 2010, retrieved 3 November 2010

- Grey, Christopher (2012), Decoding Organization: Bletchley Park, Codebreaking and Organization Studies, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107005457

- Hill, Marion (2004), Bletchley Park People, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7509-3362-9

- Hinsley, Harry (1996) [1993], The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War, archived from the original on 15 October 2022, retrieved 13 February 2015 Transcript of a lecture given on Tuesday 19 October 1993 at Cambridge University

- Hinsley, F. H.; Stripp, Alan, eds. (1993) [1992], Codebreakers: The inside story of Bletchley Park, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280132-6

- Kahn, David (1991), Seizing the Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939–1943, Houghton Mifflin Co., ISBN 978-0-395-42739-2

- Kenyon, David (10 May 2019), Bletchley Park and D-Day: The Untold Story of How the Battle for Normandy Was Won, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-24357-4

- Lewin, Ronald (2001) [1978], Ultra Goes to War: The Secret Story, Classic Military History (Classic Penguin ed.), London, England: Hutchinson & Co, ISBN 978-1-56649-231-7

- Loewe, Michael (1993), Japanese naval codes in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 257–63

- McKay, Sinclair (2010), The Secret Life of Bletchley Park: the WWII Codebreaking Centre and the Men and Women Who Worked There, Aurum, ISBN 978-1-84513-539-3

- Millward, William (1993), Life in and out of Hut 3 in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 17–29

- Milner-Barry, Stuart (1993), Navy Hut 6: Early days in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 89–99

- Morrison, Kathryn, 'A Maudlin and Monstrous Pile': The Mansion at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, English Heritage

- Pidgeon, Geoffrey (2003), The Secret Wireless War: The story of MI6 communications 1939–1945, Universal Publishing Solutions Online Ltd, ISBN 978-1-84375-252-3

- Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh (2017) [2000], Enigma: The Battle for the Code, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-1-4746-0832-9

- Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh (2000), Enigma: The Battle for the Code (Cassell Military Paperbacks ed.), London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-84251-4

- Scott, Norman (April 1997), "Solving Japanese naval ciphers 1943–1945", Cryptologia, 21 (2): 149–57, doi:10.1080/0161-119791885878

- Smith, Christopher (2015), The Hidden History of Bletchley Park: A Social and Organisational History, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1137484932

- Smith, Michael (1999) [1998], Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park, Channel 4 Books, p. 20, ISBN 978-0-7522-2189-2

- Smith, Michael (2000), The Emperor's Codes: Bletchley Park and the breaking of Japan's secret ciphers, Bantam Press, ISBN 0593-046412

- Smith, Michael (2001) [1999], "An Undervalued Effort: how the British broke Japan's Codes", in Smith, Michael; Erskine, Ralph (eds.), Action this Day, London: Bantam, ISBN 978-0-593-04910-5

- Smith, Michael (2006), How it began: Bletchley Park Goes to War in Copeland 2006, pp. 18–35

- Smith, Michael; Butters, Lindsey (2007) [2001], The Secrets of Bletchley Park: Official Souvenir Guide, Bletchley Park Trust

- Taylor, Telford (1993), Anglo-American signals intelligence co-operation in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 71–3

- Thirsk, James (2008), Bletchley Park: An Inmate's Story, Galago, ISBN 978-094699588-2

- Twinn, Peter (1993), The Abwehr Enigma in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 123–31

- Watson, Bob (1993), Appendix: How the Bletchley Park buildings took shape in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 306–10

- Welchman, Gordon (1997) [1982], The Hut Six story: Breaking the Enigma codes, Cleobury Mortimer, England: M&M Baldwin, ISBN 9780947712341 New edition with addendum by Welchman correcting his misapprehensions in the 1982 edition.

Further reading

[edit]- Comer, Tony (2021), Commentary: Poland's Decisive Role in Cracking Enigma and Transforming the UK's SIGINT Operations, Royal United Services Institute, archived from the original on 8 February 2021, retrieved 30 January 2021

- Gannon, Paul (2006), Colossus: Bletchley Park's Greatest Secret, Atlantic Books, ISBN 978-1-84354-331-2

- Gannon, Paul (2011), Inside Room 40: The Codebreakers of World War II, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7110-3408-2

- Hastings, Max (2015). The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939 -1945. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-750374-2.

- Hilton, Peter (1988), Reminiscences of Bletchley Park, 1942–1945 (PDF), pp. 291–301, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2006, retrieved 13 September 2009 (10-page preview from A Century of mathematics in America, Volume 1 By Peter L. Duren, Richard Askey, Uta C. Merzbach, see A Century of Mathematics in America: Part 1 Archived 12 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine; ISBN 978-0-8218-0124-6).

- Large, Christine (2003), Hijacking Enigma: The Insider's Tale, John Wiley, ISBN 978-0-470-86346-6

- Luke, Doreen (2005) [2003], My Road to Bletchley Park (3rd ed.), Cleobury Mortimer, Shropshire: M & M Baldwin, ISBN 978-0-947712-44-0

- McKay, Sinclair (2012), The Secret Listeners: How the Y Service Intercepted German Codes for Bletchley Park, London: Aurum, ISBN 978-1-845137-63-2

- Mahon, A. P. (1945), The History of Hut Eight 1939 – 1945, UK National Archives Reference HW 25/2, archived from the original on 9 February 2022, retrieved 10 December 2009

- Manning, Mick; Granström, Brita (2010), Taff in the WAAF, Frances Lincoln Children's Books, ISBN 978-1-84780-093-0

- O'Keefe, David (2013), One Day in August - The Untold Story Behind Canada's Tragedy at Dieppe, Alfred A. Knopf Canada, ISBN 978-0-345-80769-4

- Pearson, Joss, ed. (2011), Neil Webster's Cribs for Victory: The Untold Story of Bletchley Park's Secret Room, Polperro Heritage Press, ISBN 978-0-9559541-8-4, archived from the original on 25 March 2022, retrieved 4 September 2011

- Price, David A. (2021). Geniuses at War; Bletchley Park, Colossus, and the Dawn of the Digital Age. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-525-52154-9.

- Russell-Jones, Mair (2014), My Secret Life in Hut Six: One Woman's Experiences at Bletchley Park, Lion Hudson, ISBN 978-0-745-95664-0

- Smith, Christopher (2014), "Operating secret machines: military women and the intelligence production line, 1939–1945", Women's History Magazine, 76: 30–36, ISSN 1476-6760

- Smith, Christopher (2014), "How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park", History of Science, 52 (2): 200–222, doi:10.1177/0073275314529861, S2CID 145181963

- Turing, Dermot (2018). X, Y & Z: The Real Story of How Enigma Was Broken. Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-8782-0.

- Watkins, Gwen (2006), Cracking the Luftwaffe Codes, Greenhill Books, ISBN 978-1-85367-687-1

External links

[edit]- Bletchley Park Trust Archived 9 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Roll of Honour: List of the men and women who worked at Bletchley Park and the Out Stations during WW2, archived from the original on 18 May 2011, retrieved 9 July 2011

- Bletchley Park—Virtual Tour by Tony Sale

- The National Museum of Computing (based at Bletchley Park)

- The RSGB National Radio Centre (based at Bletchley Park)

- "New hope of saving Bletchley Park for nation". Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2019. (The Daily Telegraph 3 March 1997)

- Boffoonery! Comedy Benefit For Bletchley Park Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Comedians and computing professionals stage comedy show in aid of Bletchley Park

- Bletchley Park: It's No Secret, Just an Enigma, The Telegraph, 29 August 2009

- Bletchley Park is official charity of Shed Week 2010—in recognition of the work done in the Huts

- Saving Bletchley Park blog by Sue Black

- 19-minute Video interview on YouTube with Sue Black by Robert Llewellyn about Bletchley Park

- Douglas, Ian (25 December 2012), "Bletchley's forgotten heroes", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 26 December 2012

- C4 Station X 1999 on DVD here

- How Alan Turing Cracked The Enigma Code Imperial War Museums

- The Bletchley Park Podcast on Audioboom

- Bletchley Park Paperwork at The ICL Computer Museum

- Humanities scholars who worked in military intelligence in the Second World War

Maps

- Map of Bletchley Park site, as used during World War II

- Map of Bletchley Park site, as used 1939-1945

- Bletchley Park - Interactive Map

- Map of Bletchley Park site, as used in 2024

- View of Bletchley Park site, in 2024

- Bletchley Park

- Cryptography organizations

- Enigma machine

- Foreign Office during World War II

- Intelligence agency headquarters in the United Kingdom

- Locations in the history of espionage

- Milton Keynes

- Signals intelligence of World War II

- World War II sites in England

- Buildings and structures in Milton Keynes

- Historic house museums in Buckinghamshire

- History museums in Buckinghamshire

- Military and war museums in England

- Museums established in 1993

- Museums in Buckinghamshire

- Telecommunications museums in the United Kingdom

- Tourist attractions in Buckinghamshire

- World War II museums in the United Kingdom