Indian nationalism

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Indian nationalism is an instance of civic nationalism.[1] It is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, but was fully developed during the Indian independence movement which campaigned against British rule. Indian nationalism quickly rose to popularity in India through these united anti-colonial coalitions and movements. Independence movement figures like Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Jawaharlal Nehru spearheaded the Indian nationalist movement.

After Indian Independence, Prime Minister Nehru and his successors continued to campaign on Indian nationalism in face of border wars with both China and Pakistan. After the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 and the Bangladesh Liberation War, Indian nationalism reached its post-independence peak. However by the 1980s, religious tensions reached a boiling point and Indian nationalism sluggishly collapsed in the following decades. Despite its decline and the rise of religious nationalism, Indian nationalism and its historic figures continue to strongly influence the politics of India and reflect an opposition to the sectarian strands of Hindu nationalism and Muslim nationalism.[2][3][4][5]

National consciousness in India

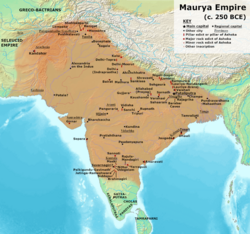

Among ancient texts, the Indian subcontinent came to be called Bharat under the rule of Bharata.[6] The Maurya Empire was the first to unite all of India, and South Asia (including parts of Afghanistan) in the 4th century BC.[7] Much of India has also been unified by later empires, such as the Mughal Empire[8] and Maratha Empire in the early modern era.[9]

Conception of Pan-South Asianism

India's concept of nationhood is based not merely on territorial extent of its sovereignty. Nationalistic sentiments and expression encompass India's ancient history[10] as the birthplace of the Indus Valley civilisation, as well as four major world religions – Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. Indian nationalists see India stretching along these lines across the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed]

Ages of war and invasion

India today celebrates many kings and queens for combating foreign invasion and domination,[11] such as Shivaji of the Maratha Empire, Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi, Kittur Chennamma, Maharana Pratap of Rajputana, Prithviraj Chauhan and Tipu Sultan. The kings of Ancient India, such as Chandragupta Maurya of the Maurya Empire and his successor Ashoka of the Magadha Empire, are also remembered for their military genius, notable conquests and remarkable religious tolerance.

The Mughal emperor Akbar was known to have a policy of religious tolerance and syncretism.[11][12]

Colonial-era nationalism

The consolidation of the British East India Company's rule in the Indian subcontinent during the late 18th century brought about socio-economic changes which led to the rise of an Indian middle class and steadily eroded pre-colonial socio-religious institutions and barriers.[13]

The emerging economic and financial power of Indian business-owners and merchants and the professional class brought them increasingly into conflict with the British authorities. A rising political consciousness among the native Indian social elite (including lawyers, doctors, university graduates, government officials and similar groups) spawned an Indian identity[14][15] and fed a growing nationalist sentiment in India in the last decades of the nineteenth century.[16] The creation in 1885 of the Indian National Congress in India by the political reformer A.O. Hume intensified the process by providing an important platform from which demands could be made for political liberalisation, increased autonomy, and social reform.[17]

The leaders of the Congress advocated dialogue and debate with the Raj administration to achieve their political goals. Distinct from these moderate voices (or loyalists) who did not preach or support violence was the nationalist movement, which grew particularly strong, radical and violent in Bengal and in Punjab. Notable but smaller movements also appeared in Maharashtra, Madras and other areas across the south.[17]

International history

British views and influence

India is a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the equator.

— Winston Churchill (1931), [1]

From the British perspective, the creation of a unified India began with and was only made possible by their conquest of the subcontinent.[19] As the rulers of India, they had an ambiguous view of Indian nationalism, envisioning a process of yielding greater autonomy to the colony while depending on it for their global dominance.[20]

British sports such as cricket became part of the nationalist movement over time, with victories against the British by unified Indian teams offering a nonviolent means to push for independence.[21] The nationalist movement also found other ways to adopt elements of British culture while opposing British rule.[22]

Other foreign influences

Giuseppe Mazzini and other figures associated with the 19th-century unification of Italy were greatly admired by many early Indian nationalists.[23] Sri Aurobindo described the nationalist sentiment of his time as the "sweet harmony between the new ideal of Mazzini and the old ideal of Sannyasa".[24]

B. R. Ambedkar, a major figure in the postcolonial drafting of the modern Indian Constitution, took note of the historical challenges of nation-building in several other societies.[25] He was influenced by his education at Columbia University in the United States.[26][27]

International networks

By the early 20th century, Pan-Asianism became part of anticolonial discourse within the nationalist movement.[28]

Swadeshi

The controversial 1905 partition of Bengal escalated the growing unrest, stimulating radical nationalist sentiments and becoming a driving force for Indian revolutionaries.[30]

The Gandhian era

Mahatma Gandhi pioneered the art of Satyagraha, typified with a strict adherence to ahimsa (non-violence), and civil disobedience. This permitted common individuals to engage the British in revolution, without employing violence or other distasteful means. Gandhi's equally strict adherence to democracy, religious and ethnic equality and brotherhood, as well as activist rejection of caste-based discrimination and untouchability united people across these demographic lines for the first time in India's history. The masses participated in India's independence struggle for the first time, and the membership of the Congress grew over tens of millions by the 1930s. In addition, Gandhi's victories in the Champaran and Kheda Satyagraha in 1918–19, gave confidence to a rising younger generation of Indian nationalists that India could gain independence from British rule.

National leaders like Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Maulana Azad, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, Rajendra Prasad, the Lal Bal Pal trio, and Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan brought together generations of Indians across regions and demographics, and provided a strong leadership base giving the country political direction.

Final years

In 1947, Lord Mountbatten came to India to discuss the eventual outcome of the British departure. At one point, he offered a plan to Nehru to make the various regions of India autonomous provinces, which Nehru strongly rejected;[31] Lakshman Menon, grandson of Nehru's principal adviser V. P. Menon, referred to the plan as "Plan Balkan" (in reference to Balkanisation).[32]

Independence

Upon independence on 15 August of that year, India maintained formal links with the dissolving British Empire through its Commonwealth membership and Dominion status.[33] The latter was abandoned in 1950, an anniversary now celebrated as Republic Day.[34]

Beyond Indian nationalism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2019) |

Indian nationalism is as much a diverse blend of nationalistic sentiments as its people are ethnically and religiously diverse. Thus the most influential undercurrents are more than just Indian in nature. The most controversial and emotionally charged fibre in the fabric of Indian nationalism is religion. Religion forms a major, and in many cases, the central element of Indian life. Religious nationalisms are often dependent on mutual opposition.[35] Ethnic communities are diverse in terms of linguistics, social traditions and history across India.[36]

Hindu Rashtra

An important influence upon Hindu consciousness arises from the time of Islamic empires in India. Entering the 20th century, Hindus formed over 75% of the population and thus unsurprisingly the backbone and platform of the nationalist movement. Modern Hindu thinking desired to unite Hindu society across the boundaries of caste, linguistic groups and ethnicity. In 1925, K.B. Hedgewar founded the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in Nagpur, Maharashtra, which grew into the largest civil organisation in the country, and the most potent, mainstream base of Hindu nationalism.[38]

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar coined the term Hindutva for his ideology that described India as a Hindu Rashtra, a Hindu nation. This ideology has become the cornerstone of the political and religious agendas of modern Hindu nationalist bodies like the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad. Hindutva political demands include revoking Article 370 of the Constitution that granted a special semi-autonomous status to the Muslim-majority state of Kashmir, and adopting a uniform civil code, thus ending special legal frameworks for different religions in the country.[39] These particular demands are based upon ending laws that Hindu nationalists consider to be special treatment offered to different religions.[40]

The Qaum

In 1906–1907, the All-India Muslim League was founded, created due to the suspicion of Muslim intellectuals and religious leaders with the Indian National Congress, which was perceived as dominated by Hindu membership and opinions. However, Mahatma Gandhi's leadership attracted a wide array of Muslims to the independence struggle and the Congress Party. The Aligarh Muslim University and the Jamia Millia Islamia stand apart – the former helped form the Muslim league, while the JMI was founded to promote Muslim education and consciousness upon nationalistic and Gandhian values and thought.

While prominent Muslims like Allama Iqbal, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan embraced the notion that Hindus and Muslims were distinct nations, other major leaders like Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, Maulana Azad and most of Deobandi clerics strongly backed the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian independence struggle, opposing any notion of Muslim nationalism and separatism. The Muslim school of Indian nationalism failed to attract Muslim masses and the Islamic nationalist Muslim League enjoyed extensive popular political support. The state of Pakistan was ultimately formed following the Partition of India.

Views on the partition of India

Indian nationalists led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to make what was then British India, as well as the 562 princely states under British paramountcy, into a single secular, democratic state.[42] The All India Azad Muslim Conference, which represented nationalist Muslims, gathered in Delhi in April 1940 to voice its support for an independent and united India.[43] The British Government, however, sidelined the 'All India' organization from the independence process and came to see Jinnah, who advocated separatism, as the sole representative of Indian Muslims.[44] This was viewed with dismay by many Indian nationalists, who viewed Jinnah's ideology as damaging and unnecessarily divisive.[45]

In an interview with Leonard Mosley, Nehru said that he and his fellow Congressmen were "tired" after the independence movement, so were not ready to further drag on the matter for years with Jinnah's Muslim League, and that, anyway, they "expected that partition would be temporary, that Pakistan would come back to us."[47] Gandhi also thought that the Partition would be undone.[48] V.P. Menon, who had an important role in the transfer of power in 1947, quotes another major Congress politician, Abul Kalam Azad, who said that "the division is only of the map of the country and not in the hearts of the people, and I am sure it is going to be a short-lived partition."[49] Acharya Kripalani, President of the Congress during the days of Partition, stated that making India "a strong, happy, democratic and socialist state" would ensure that "such an India can win back the seceding children to its lap... for the freedom we have achieved cannot be complete without the unity of India."[50] Yet another leader of the Congress, Sarojini Naidu, said that she did not consider India's flag to be India's because "India is divided" and that "this is merely a temporary geographical separation. There is no spirit of separation in the heart of India."[51]

Giving a more general assessment, Paul Brass says that "many speakers in the Constituent Assembly expressed the belief that the unity of India would be ultimately restored."[52]

Khalistan

The Khalistan movement is a separatist movement seeking to create a homeland for Sikhs by establishing an ethno-religious sovereign state called Khalistan (lit. 'land of the Khalsa') in the Punjab region.[54] The proposed boundaries of Khalistan vary between different groups; some suggest the entirety of the Sikh-majority Indian state of Punjab, while larger claims include Pakistani Punjab and other parts of North India such as Chandigarh, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh.[55]

The call for a separate Sikh state began during the 1930s, when British rule in India was nearing its end.[56] In 1940, the first explicit call for Khalistan was made in a pamphlet titled "Khalistan".[57][58] In the 1940s, a demand for a Sikh country called 'Sikhistan' arose.[59] With financial and political support from the Sikh diaspora, the movement flourished in the Indian state of Punjab – which has a Sikh-majority population – continuing through the 1970s and 1980s, and reaching its zenith in the late 1980s. The Sikh separatist leader Jagjit Singh Chohan said that during his talks with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the latter affirmed his support for the Khalistan movement in retaliation for the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war, which resulted in the secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan.[60]Contemporary era

After independence, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel helped complete the political integration of India. In 2014, his birthday was declared National Unity Day,[61] and in 2018, he was commemorated in his native Gujarat with the Statue of Unity.[62]

Along with dealing with the princely states, reorganising the states on linguistic boundaries was a central question in deciding the nature of the new nation. The government initially hesitated to support such a move, fearing it would lead to separatism, but eventually acquiesced with the States Reorganisation Act, 1956.[63]

In these initial decades, the Hindi language was proposed by some as a national language, and was deliberately Sanskritised to distinguish it from the Urdu spoken in the newly separate Pakistan. Some of the strong advocates of Hindi associated it with Hindu nationalism through the slogan "Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan".[64] Hindi cinema (popularly known as Bollywood) played a role in offering a vision of a unified India, with films celebrating military valour in border conflicts.[65]

Post-Cold War

Economic liberalisation in the 1990s greatly changed India, with a greater amount of globalisation and transnationalism taking hold in the popular culture.[68]

For the 75th Anniversary of Indian Independence in 2022, the Har Ghar Tiranga campaign was launched, encouraging every household to display the Indian flag.[69]

See also

- Pan-Indian

- Varthamanappusthakam – Travelogue written in Malayalam in 1790s

References

- ^ "India's Journey from Civic to Cultural Nationalism: A New Political Imaginary? (Article)".

- ^ Lerner, Hanna (12 May 2011), Making Constitutions in Deeply Divided Societies, Cambridge University Press, pp. 120–, ISBN 978-1-139-50292-4

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (1999), The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s : Strategies of Identity-building, Implantation and Mobilisation (with Special Reference to Central India), Penguin Books India, pp. 13–15, 83, ISBN 978-0-14-024602-5

- ^ Pachuau, Lalsangkima; Stackhouse, Max L. (2007), News of Boundless Riches, ISPCK, pp. 149–150, ISBN 978-81-8458-013-6

- ^ Leifer, Michael (2000), Asian Nationalism, Psychology Press, pp. 112–, ISBN 978-0-415-23284-5

- ^ Vyasa, Dwaipayana (24 August 2021). The Mahabharata of Vyasa: (Complete 18 Volumes). Enigma Edizioni. p. 2643.

- ^ "Mauryan Empire". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Vyasa, Dwaipayana (24 August 2021). The Mahabharata of Vyasa: (Complete 18 Volumes). Enigma Edizioni. p. 2643.

- ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Acharya, Shiva. "Nation, Nationalism and Social Structure in Ancient India By Shiva Acharya". Sundeepbooks.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Mahrattas, Sikhs and Southern Sultans of India : Their Fight Against Foreign Power/edited by H.S. Bhatia". Vedamsbooks.com. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Lane-Poole, Stanley. Jackson, A. V. Williams (ed.). History of India. London: Grolier society. pp. 26-.

- ^ Mitra 2006, p. 63

- ^ Croitt & Mjøset 2001, p. 158

- ^ Desai 2005, p. xxxiii

- ^ Desai 2005, p. 30

- ^ a b Yadav 1992, p. 6

- ^ Kamm, Josephine (1946). "Self-Government in the British Dependent Empire". World Affairs. 109 (4): 280–285. ISSN 0043-8200.

- ^ Sen, Amartya (29 June 2021). "Illusions of empire: Amartya Sen on what British rule really did for India". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

- ^ Huttenback, Robert A (1999). "Britain and Indian Nationalism: Imprint of Ambiguity, 1929-1942 (review)". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 30 (1): 175–177. doi:10.1162/jinh.1999.30.1.175. ISSN 1530-9169.

- ^ Majumdar, Boria; and Brown, Sean (1 February 2007). "Why baseball, why cricket? differing nationalisms, differing challenges". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 24 (2): 139–156. doi:10.1080/09523360601045732. ISSN 0952-3367.

- ^ Tharoor, Shashi (5 April 2018). "Cricket: The Nationalist Game". Open The Magazine. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

- ^ Paul, Sudeep (13 August 2020). "The Enigma of Heroes". Open The Magazine. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Gupta, R. K. Das (1956). "Mazzini and Indian Nationalism". East and West. 7 (1): 67–70. ISSN 0012-8376.

- ^ "Dr. Ambedkar, The Architect Of Inclusive Indian Nationalism". Outlook India. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Stroud, Scott (31 May 2024). "The American Question: Ambedkar, Columbia University, and the "Spirit of Rebellion"". CASTE / A Global Journal on Social Exclusion. 5 (2): 270–286. doi:10.26812/caste.v5i2.694. ISSN 2639-4928.

- ^ Pattekar, Mandar (30 May 2023). "The Profound Influence America Had On the Life and Ideology of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar". American Kahani. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Stolte, Carolien; Fischer-Tiné, Harald (2012). "Imagining Asia in India: Nationalism and Internationalism (ca. 1905–1940)". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 54 (1): 65–92. doi:10.1017/S0010417511000594. ISSN 1475-2999.

- ^ Menon, Nikhil (2020). "Gandhi's Spinning Wheel: The Charkha and Its Regenerative Effects". Journal of the History of Ideas. 81 (4): 643–662. ISSN 1086-3222.

- ^ Bose & Jalal 1998, p. 117

- ^ "From the archives: How Jawaharlal Nehru foiled a British plan to Balkanise India". India Today. 26 May 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ "'Plan Balkan' that hit Jawaharlal Nehru wall". Archived from the original on 19 April 2025. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ Panter-Brick, Simone (16 December 2014). Gandhi and Nationalism: The Path to Indian Independence. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7556-3222-0.

- ^ De, Rohit (31 December 2019). "Between midnight and republic: Theory and practice of India's Dominion status". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 17 (4): 1213–1234. doi:10.1093/icon/moz081. ISSN 1474-2640.

- ^ Veer, Peter van der (7 February 1994). Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08256-4.

- ^ Lobo, Lancy (2002). Globalisation, Hindu nationalism, and Christians in India. Jaipur: Rawat Publications. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-7033-716-4.

- ^ Ayyub, Rana (29 January 2024). "Hindu nationalism overtakes India's patriotic holiday". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh | History, Ideology, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "What is Uniform Civil Code?". Jagranjosh.com. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "WHAT IS UNIFORM CIVIL CODE". Business Standard. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "MINURSO'S PEACEKEEPERS: NATIONAL DAY OF PAKISTAN". MINURSO. 14 August 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Hardgrave, Robert. "India: The Dilemmas of Diversity", Journal of Democracy, pp. 54–65

- ^ Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017). Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781108621236.

- ^ Qaiser, Rizwan (2005), "Towards United and Federate India: 1940-47", Maulana Abul Kalam Azad a study of his role in Indian Nationalist Movement 1919–47, Jawaharlal Nehru University/Shodhganga, Chapter 5, pp. 193, 198, hdl:10603/31090

- ^ Raj Pruthi, Paradox of Partition: Partition of India and the British strategy, Sumit Enterprises (2008), p. 444

- ^ Graham Chapman, The Geopolitics of South Asia: From Early Empires to the Nuclear Age, Ashgate Publishing (2012), p. 326

- ^ Sankar Ghose, Jawaharlal Nehru, a Biography, Allied Publishers (1993), pp. 160-161

- ^ Raj Pruthi, Paradox of Partition: Partition of India and the British strategy, Sumit Enterprises (2008), p. 443

- ^ V.P. Menon, The Transfer of Power in India, Orient Blackswan (1998), p. 385

- ^ G. C. Kendadamath, J.B. Kripalani, a study of his political ideas, Ganga Kaveri Pub. House (1992), p. 59

- ^ Constituent Assembly Debates: Official Report, Volume 4, Lok Sabha secretariat, 14 July 1947, p. 761

- ^ Paul R. Brass, The Politics of India Since Independence, Cambridge University Press (1994), p. 10

- ^ Shah, Murtaza Ali (27 January 2022). "Khalistan flag installed on Gandhi Statue in Washington". Geo News. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Kinnvall, Catarina (24 January 2007). "Situating Sikh and Hindu Nationalism in India". Globalization and Religious Nationalism in India: The Search for Ontological Security. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13-413570-7. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Crenshaw, Martha (1995). Terrorism in Context, Pennsylvania State University, ISBN 978-0-271-01015-1. p. 364.

- ^ Axel, Brian Keith (2001). The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora". Duke University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8223-2615-1. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

The call for a Sikh homeland was first made in the 1930s, addressed to the quickly dissolving empire.

- ^ Shani, Giorgio (2007). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-134-10189-4. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

However, the term Khalistan was first coined by Dr V.S. Bhatti to denote an independent Sikh state in March 1940. Dr Bhatti made the case for a separate Sikh state in a pamphlet entitled 'Khalistan' in response to the Muslim League's Lahore Resolution.

- ^ Bianchini, Stefano; Chaturvedi, Sanjay; Ivekovic, Rada; Samaddar, Ranabir (2004). Partitions: Reshaping States and Minds. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-134-27654-7. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

Around the same time, a pamphlet of about forty pages, entitled 'Khalistan', and authored by medical doctor, V.S. Bhatti, also appeared.

- ^ Larson, Gerald James (16 February 1995). India's Agony Over Religion: Confronting Diversity in Teacher Education (Reprint ed.). SUNY Press. p. 190. ISBN 9780791424124.

- ^ Gupta, Shekhar; Subramanian, Nirupaman (15 December 1993). "You can't get Khalistan through military movement: Jagat Singh Chouhan". India Today. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Staff, Scroll (31 October 2019). "What is National Unity Day and why is it celebrated on 31st October?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- ^ "5 Years of Statue of Unity: Facts About the World's Tallest Statue". www.ndtv.com. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Tudor, Maya (2018). "India's Nationalism in Historical Perspective: The Democratic Dangers of Ascendant Nativism". Indian Politics & Policy. 1 (1): 116. doi:10.18278/inpp.1.1.6.

- ^ Aneesh, A. (2010). "Bloody Language: Clashes and Constructions of Linguistic Nationalism in India". Sociological Forum. 25 (1): 86–109. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01158.x. ISSN 1573-7861.

- ^ Karmakar, Goutam; and Catterall, Pippa (15 March 2025). "Nation, Nationalism and Indian Hindi cinema". National Identities. 27 (1–2): 1–11. doi:10.1080/14608944.2024.2440753. ISSN 1460-8944.

- ^ Kidambi, Prashant (2011), Bateman, Anthony; Hill, Jeffrey (eds.), "Hero, celebrity and icon: Sachin Tendulkar and Indian public culture", The Cambridge Companion to Cricket, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 187–202, ISBN 978-0-521-76129-1, retrieved 17 May 2025

- ^ Shamsie, Kamila (23 May 2017). "Sachin Tendulkar: 'When I was injured I could not sleep at night'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Saha, Ratan Kr (15 April 2025). "Reimagining National Identity: The Intersection of Cultural Narratives and Postmodern Nationalism in India Post-1990s". The Academic – International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research. doi:10.5281/zenodo.15223681.

- ^ "BJP launches 'Har Ghar Tiranga' drive in Chhattisgarh". The Times of India. 6 August 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

Bibliography

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (1998), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16952-6

- Croitt, Raymond D; Mjøset, Lars (2001), When Histories Collide, Oxford, UK: AltaMira, ISBN 0-7591-0158-2

- Desai, A.R. (2005), Social Background of Indian Nationalism (6Th-Edn), Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-667-1

- Mitra, Subrata K. (2006), The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-27493-2

- Mukherjee, Bratindra Nath (2001), Nationhood and Statehood in India: A historical survey, Regency Publications, ISBN 978-81-87498-26-1

- Yadav, B.D (1992), M.P.T. Acharya, Reminiscences of an Indian Revolutionary, New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt ltd, ISBN 81-7041-470-9

External links

Media related to Indian nationalism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Indian nationalism at Wikimedia Commons