Aesthetics

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.[1] Aesthetics examines values about, and critical judgments of, artistic taste and preference.[2] It thus studies how artists imagine, create, and perform works of art, as well as how people use, enjoy, and criticize art. Aesthetics considers why people consider certain things beautiful and not others, as well as how objects of beauty and art can affect our moods and our beliefs.[3]

Aesthetics tries to find answers to what exactly is art and what makes good art. It considers what happens in our minds when we view visual art, listen to music, read poetry, enjoy delicious food, and engage in large artistic projects like creating and experiencing plays, fashion shows, films, and television programs. It can also focus on how humans regard various forms of beauty in the natural world. Its function is the "critical reflection on art, culture and nature".[4][5]

Definition

[edit]

Aesthetics, sometimes spelled esthetics,[6] is the branch of philosophy that studies the beauty, art, and taste. It examines which types of aesthetic phenomena there are, how people experience them, and how objects evoke them. This field also investigates the nature of aesthetic judgments, the meaning of artworks, and the problem of art criticism.[7] Key questions in aesthetics include "What is art?", "Can aesthetic judgments be objective?", and "How is aesthetic value related to other values?".[8] One characterization distinguishes between three main approaches to aesthetics: the study of aesthetic concepts and judgments, the study of aesthetic experiences and other mental responses, and the study of the nature and features of aesthetic objects.[9] In a slightly different sense, the term aesthetics can also refer to particular theories of beauty or to beautiful appearances.[10]

Aesthetics is closely related to the philosophy of art and the two terms are often used interchangeably since both involve the philosophical study of aesthetic phenomena. One difference is that the philosophy of art focuses on art, whereas the scope of aesthetics also includes other domains, such as beauty in nature and everyday life. This leads some theorists to argue that the philosophy of art is a subfield of aesthetics.[11] However, the precise relation between the two fields is disputed and another characterization holds that the philosophy of art is the broader discipline. This view argues that aesthetics mainly addresses aesthetic properties, while the philosophy of art also investigates non-aesthetic features of artworks, belonging to fields such as ontology, epistemology, philosophy of language, and ethics.[12]

Even though the philosophical study of aesthetic problems originated in antiquity, it was not until the 18th century that aesthetics emerged as a distinct branch of philosophy when philosophers engaged in systematic inquiry into its principles.[13] The term "aesthetics" was coined by the German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten in 1735, initially defined as the study of sensibility or sensations of beautiful objects.[14] The term comes from the ancient Greek words aisthetikos, meaning 'perceptible things', aisthesthai, meaning 'perceive, see', and aesthesis, meaning 'sensation, perception'.[15] The earliest known use in the English language happened in a translation by W. Hooper in the 1770s.[16]

History of aesthetics

[edit]The history of the philosophy of art as aesthetics covering the visual arts, the literary arts, the musical arts and other artists forms of expression can be dated back at least to Aristotle and the ancient Greeks. Aristotle writing of the literary arts in his Poetics stated that epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and dance are all fundamentally acts of mimesis, each varying in imitation by medium, object, and manner.[17][18] Aristotle applies the term mimesis both as a property of a work of art and also as the product of the artist's intention[17] and contends that the audience's realisation of the mimesis is vital to understanding the work itself.[17]

Aristotle states that mimesis is a natural instinct of humanity that separates humans from animals[17][19] and that all human artistry "follows the pattern of nature".[17] Because of this, Aristotle believed that each of the mimetic arts possesses what Stephen Halliwell calls "highly structured procedures for the achievement of their purposes."[20] For example, music imitates with the media of rhythm and harmony, whereas dance imitates with rhythm alone, and poetry with language.

The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitation – through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama.[21]

Basic concepts

[edit]The domain of the aesthetic encompasses a variety of properties, objects, experiences, and judgments associated with beauty and artistic expression. However, the exact boundaries of this domain are disputed—it is controversial whether there is a group of essential features shared by all aesthetic phenomena or whether they are more loosely related through family resemblances. Another central topic concerns the relation between different aesthetic concepts, for example, whether the concept "aesthetic object" is defined through the concept of "aesthetic experience".[22]

Aesthetic properties and objects

[edit]

Aesthetic properties of an object are features that shape its aesthetic appeal or factors that influence aesthetic evaluations. For instance, when an art critic describes an artwork as great, vivid, or amusing, they express aesthetic properties of this artwork. Aesthetic properties cover a wide range of features. Some focus on aesthetic value in general, like great and ugly, while others center on more specific forms of value, such as graceful and elegant. Aesthetic properties can also refer to perceptual qualities of objects like balanced and vivid, to representational aspects like realistic and distorted, or to emotional responses such as joyful and angry.[23]

The precise distinction between aesthetic and non-aesthetic properties is disputed. According to one proposal, aesthetic properties require a specific aesthetic sensitivity in addition to the sensory perception of non-aesthetic properties, going beyond simple colors, shapes, and sounds. Aesthetic properties are associated with evaluations, but not all are intrinsically good or bad. For example, being a realistic representation may be aesthetically good in some artistic contexts and bad in others.[24]

The school of realism argues that aesthetic properties are objective, mind-independent features of reality. A related proposal asserts that they are emergent properties dependent on non-aesthetic properties. According to this view, the beauty of a painting may emerge from the right combination of colors and shapes. A different position holds that aesthetic properties are response-dependent, for example, that features of objects only qualify as aesthetic properties if they evoke aesthetic experiences in observers.[25] The terms "aesthetic property" and "aesthetic quality" are often used interchangeably to refer to aspects such as beauty, sublimity, and grandeur. However, some philosophers distinguish the two, associating aesthetic properties with objective features and aesthetic qualities with subjective experiences and emotional responses.[26]

An aesthetic object is an object with aesthetic properties. One interpretation suggests that aesthetic objects are material entities that evoke aesthetic experiences. According to this view, if a person admires an oil painting then the physical canvas and paint make up the aesthetic object. Another interpretation, associated with the school of phenomenology, argues that aesthetic objects are not material but intentional objects. Intentional objects are part of the content of experiences and their existence depends on the perceiver. An intentional object may accurately reflect a material object, as in the case of veridical perceptions, but can also fail to do so, which happens during perceptual illusions. The phenomenological perspective focuses on the intentional object given in experience rather than the material object considered independently of the perceiver.[27]

Aesthetic values and beauty

[edit]Aesthetic values are a special type of aesthetic properties. They express the sensory appeal of an object as a qualitative measure of how pleasing it is. Aesthetic values contrast with values in other domains, such as moral, epistemic, religious, and economic values. Beauty is usually considered the main aesthetic value, but not the only one. For example, the sublime is another value of things that inspire a feeling of awe and fear. Further suggested values include charm, elegance, harmony, and grace. Historically, pre-modern philosophers typically rejected the idea of multiple distinct aesthetic values. They tended to argue that beauty alone encompasses all that is aesthetically commendable and serves as a unifying concept of the whole domain of aesthetics. Aesthetic values are either positive, like beautiful and sublime, or negative, such as clumsy and boring.[28] Various attempts have been made to explain why some objects have positive aesthetic values, proposing features like unity, intensity, and the right level of complexity.[29]

The aesthetic value of beauty is often singled out as a central topic of aesthetics.[30] It is a key aspect of human experience, influencing both personal decisions and cultural developments.[31] Examples of beautiful objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans, and artworks. As a positive value, beauty contrasts with ugliness as its negative counterpart. Beauty is typically understood as a quality of objects that involves balance or harmony and evokes admiration or pleasure when perceived, but its precise definition is debated.[32]

Various theoretical disputes surround the nature of beauty and its role in aesthetics. Some theories understand beauty as an objective feature of external objects. Others emphasize its subjective nature, linking it to personal experience and perception. They argue that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder" rather than in the perceived object.[33] Another central debate concerns the features that all beautiful objects have in common. The classical conception of beauty is rooted in classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. Focusing on objective features, it asserts that beauty is an harmonious arrangement of parts into a coherent whole. Aesthetic hedonism, by contrast, is a subjective theory holding that a thing is beautiful if it acts as a source of aesthetic pleasure. Other conceptions define beautiful objects in terms of intrinsic value, the manifestation of ideal forms, or as what evokes love and passion.[34]

Aesthetic experiences, attitude, and pleasure

[edit]An aesthetic experience is an appreciation of beauty or an awareness of other aesthetic features. In its most typical form, it is a sensory perception of a natural object or an artwork. However, it can also take other forms, such as aesthetic imagination[a] of fictional objects described in literature.[36] Internalist theories, like Monroe Beardsley's view, explain aesthetic experience from a first-person perspective, focusing on aspects internal to the experience, such as focus and intensity. By contrast, externalist theories, such as George Dickie's position, argue that the key element of aesthetic experiences comes from the experienced external objects and their aesthetic properties.[37]

Diverse features are associated with aesthetic experiences, but it is controversial whether any of them are essential. Aesthetic experiences usually appreciate an object for its own sake because of its sensory properties, resulting in aesthetic pleasure from a positive evaluation of the object. This pleasure is typically said to be detached from practical concerns and can involve selfless absorption, allowing imaginative freedom or free play of mental faculties in addition to sensory perception. Some theorists associate this free play with an absence of conceptual activity. Aesthetic experiences may also be normative, meaning that certain responses are appropriate, like the positive appreciation of beauty, but others are not, such as the positive appreciation of ugliness.[38]

A central aspect of aesthetic experience is the aesthetic attitude—a special way of observing or engaging with art and nature. This attitude involves a form of pure appreciation of perceptual qualities detached from personal desires and practical concerns. It is disinterested in this sense by engaging with an object for its own sake without ulterior motives or practical consequences. For example, the experience of a violent storm through the aesthetic attitude may focus on its intricate patterns of lightning and thunder rather than preparing for its immediate dangers. One characterization understands the aesthetic attitude as a natural form of apprehension that occurs on its own in certain situations. Another outlook holds that the aesthetic attitude is a voluntary stance people can choose to adopt towards any object.[39] There is debate about the extent and type of emotional engagement a disinterested stance requires, for instance, whether fear during a horror movie can be disinterested.[40]

The aesthetic attitude is sometimes contrasted with other attitudes, such as the practical attitude, which is interested in usefulness and seeks to utilize or manipulate objects to achieve specific goals. Similarly, it differs from the scientific attitude, which aims to explain phenomena and acquire factual knowledge about the world.[41] Some philosophers, such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Martin Heidegger, suggest that the aesthetic attitude can reveal aspects of reality obscured in other attitudes.[42]

Aesthetic experience is further associated with aesthetic pleasure—a form of enjoyment in response to natural and artistic beauty. It is typically characterized as disinterested pleasure. It contrasts with interested pleasure that arises from the satisfaction of desires, such as the joy of achieving a personal goal or indulging in a particular type of food one craved. Another difference is that aesthetic pleasure does not depend on the existence of the enjoyed object, like enjoying the beauty of a sunset in a dream. The joy in achieving a personal goal, by contrast, would be frustrated if one discovered that the achievement was merely a dream.[43] Philosophers like Immanuel Kant argue that aesthetic pleasure is pre-conceptual, meaning that it arises from a free interplay between imagination and understanding rather than from cognitive judgments or conceptual analysis.[44] Some theorists distinguish refined from unrefined aesthetic pleasures based on whether the pleasure is evoked by a cultivated taste or an immediate, instinctual response.[45]

Aesthetic pleasure is central to the characterization of various aesthetic phenomena, which are said to involve or evoke such pleasure. However, the view that aesthetic pleasure is the defining characteristic of the entire aesthetic domain is controversial. It faces challenges in explaining phenomena such as the sublime, drama, tragedy, and various forms of modern art, which may evoke diverse emotions not primarily linked to pleasure.[46]

Aesthetic judgments and taste

[edit]

Aesthetic judgments are assessments of the aesthetic features and values of objects, expressed in statements like "this music is beautiful". They can apply both to natural objects and artworks. Aesthetic judgments also include assessments about how or why an object has aesthetic value without explicitly determine its overall aesthetic worth, as in the statement "this music is balanced". Many debates in aesthetics concern the nature of aesthetic judgments, in particular, whether they can be as objective and universal as empirical judgments made by natural scientists. Subjectivists argue that aesthetic judgments express personal feelings and dislikes without universal validity. This view is contested by objectivists, who hold that aesthetic judgments describe objective features that are independent of the particular preferences of the judging individual. Intermediate views suggest that the standards of aesthetic judgment are grounded in stable shared dispositions rather than variable individual preferences, resulting in a form of subjective universality.[47] This position is reflected in Kant's view, which identifies four core features of aesthetic judgments: they are subjective, universal, disinterested, and involve an interplay of sense, imagination, and understanding.[48]

Philosophers such as Francis Hutcheson and David Hume argue that there are general aesthetic principles or universal criteria that are applied when making aesthetic judgments. Particularists, by contrast, assert that the unique nature of each aesthetic object requires a case-by-case evaluation that cannot be fully subsumed under general principles.[49] A related debate between rationalism and the immediacy thesis concerns whether aesthetic judgments are mediated through concept application and reasoning or emerge directly from sensory intuition.[50]

Aesthetic judgments rely on taste,[b] which is a sensitivity to aesthetic qualities, a capacity to feel aesthetic pleasure, or an ability to discern beauty and other aesthetic qualities. Taste is a type of preference expressed in immediate reactions and is sometimes understood as an inner sense or cognitive faculty. Differences in taste are often used to explain why people disagree about aesthetic judgments and why the judgments of some people, such as art critics with extensive experience and a refined sense, carry more weight than those of casual observers. Taste varies both between cultures and between individuals within a culture[c]. However, there are also some cross-cultural agreements. Various philosophers argue that taste can be learned to some extent and that the judgments of experienced observers follow similar standards, suggesting the existence of social norms of right and wrong aesthetic assessments.[53]

The term "aesthetic universal" refers to aspects of taste and other aesthetic phenomena that are shared across different cultures and societies, indicating common features of human nature underlying aesthetics. Suggested general tendencies include the dispositions to engage in artistic expressions or to derive aesthetic pleasure from appreciating these expressions. The existence of more specific shared tendencies is debated. An example is the idea that humans generally find savanna-like landscapes with open grassy plains and scattered trees pleasing.[54]

New Criticism and "The Intentional Fallacy"

[edit]During the first half of the twentieth century, a significant shift to general aesthetic theory took place which attempted to apply aesthetic theory between various forms of art, including the literary arts and the visual arts, to each other. This resulted in the rise of the New Criticism school and debate concerning the intentional fallacy. At issue was the question of whether the aesthetic intentions of the artist in creating the work of art, whatever its specific form, should be associated with the criticism and evaluation of the final product of the work of art, or, if the work of art should be evaluated on its own merits independent of the intentions of the artist.[citation needed]

In 1946, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley published a classic and controversial New Critical essay entitled "The Intentional Fallacy", in which they argued strongly against the relevance of an author's intention, or "intended meaning" in the analysis of a literary work. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, the words on the page were all that mattered; importation of meanings from outside the text was considered irrelevant, and potentially distracting.[citation needed]

In another essay, "The Affective Fallacy," which served as a kind of sister essay to "The Intentional Fallacy", Wimsatt and Beardsley also discounted the reader's personal/emotional reaction to a literary work as a valid means of analyzing a text. This fallacy would later be repudiated by theorists from the reader-response school of literary theory. One of the leading theorists from this school, Stanley Fish, was himself trained by New Critics. Fish criticizes Wimsatt and Beardsley in his essay "Literature in the Reader" (1970).[55]

As summarized by Berys Gaut and Livingston in their essay "The Creation of Art": "Structuralist and post-structuralists theorists and critics were sharply critical of many aspects of New Criticism, beginning with the emphasis on aesthetic appreciation and the so-called autonomy of art, but they reiterated the attack on biographical criticisms' assumption that the artist's activities and experience were a privileged critical topic."[56] These authors contend that: "Anti-intentionalists, such as formalists, hold that the intentions involved in the making of art are irrelevant or peripheral to correctly interpreting art. So details of the act of creating a work, though possibly of interest in themselves, have no bearing on the correct interpretation of the work."[57]

Gaut and Livingston define the intentionalists as distinct from formalists stating that: "Intentionalists, unlike formalists, hold that reference to intentions is essential in fixing the correct interpretation of works." They quote Richard Wollheim as stating that, "The task of criticism is the reconstruction of the creative process, where the creative process must in turn be thought of as something not stopping short of, but terminating on, the work of art itself."[57]

Derivative forms of aesthetics

[edit]A large number of derivative forms of aesthetics have developed as contemporary and transitory forms of inquiry associated with the field of aesthetics which include the post-modern, psychoanalytic, scientific, and mathematical among others.[citation needed]

Post-modern aesthetics and psychoanalysis

[edit]Early-twentieth-century artists, poets and composers challenged existing notions of beauty, broadening the scope of art and aesthetics. In 1941, Eli Siegel, American philosopher and poet, founded Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy that reality itself is aesthetic, and that "The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites."[58][59]

Various attempts have been made to define Post-Modern Aesthetics. The challenge to the assumption that beauty was central to art and aesthetics, thought to be original, is actually continuous with older aesthetic theory; Aristotle was the first in the Western tradition to classify "beauty" into types as in his theory of drama, and Kant made a distinction between beauty and the sublime. What was new was a refusal to credit the higher status of certain types, where the taxonomy implied a preference for tragedy and the sublime to comedy and the Rococo.

Croce suggested that "expression" is central in the way that beauty was once thought to be central. George Dickie suggested that the sociological institutions of the art world were the glue binding art and sensibility into unities.[60] Marshall McLuhan suggested that art always functions as a "counter-environment" designed to make visible what is usually invisible about a society.[61] Theodor Adorno felt that aesthetics could not proceed without confronting the role of the culture industry in the commodification of art and aesthetic experience. Hal Foster attempted to portray the reaction against beauty and Modernist art in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Arthur Danto has described this reaction as "kalliphobia" (after the Greek word for beauty, κάλλος kallos).[62] André Malraux explains that the notion of beauty was connected to a particular conception of art that arose with the Renaissance and was still dominant in the eighteenth century (but was supplanted later). The discipline of aesthetics, which originated in the eighteenth century, mistook this transient state of affairs for a revelation of the permanent nature of art.[63] Brian Massumi suggests to reconsider beauty following the aesthetical thought in the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari.[64] Walter Benjamin echoed Malraux in believing aesthetics was a comparatively recent invention, a view proven wrong in the late 1970s, when Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake analyzed links between beauty, information processing, and information theory. Denis Dutton in "The Art Instinct" also proposed that an aesthetic sense was a vital evolutionary factor.

Jean-François Lyotard re-invokes the Kantian distinction between taste and the sublime. Sublime painting, unlike kitsch realism, "... will enable us to see only by making it impossible to see; it will please only by causing pain."[65][66]

Sigmund Freud inaugurated aesthetical thinking in Psychoanalysis mainly via the "Uncanny" as aesthetical affect.[67] Following Freud and Merleau-Ponty,[68] Jacques Lacan theorized aesthetics in terms of sublimation and the Thing.[69]

The relation of Marxist aesthetics to post-modern aesthetics is still a contentious area of debate.

Aesthetics and science

[edit]The field of experimental aesthetics was founded by Gustav Theodor Fechner in the 19th century. Experimental aesthetics in these times had been characterized by a subject-based, inductive approach. The analysis of individual experience and behaviour based on experimental methods is a central part of experimental aesthetics. In particular, the perception of works of art,[70] music, sound,[71] or modern items such as websites[72] or other IT products[73] is studied. Experimental aesthetics is strongly oriented towards the natural sciences. Modern approaches mostly come from the fields of cognitive psychology (aesthetic cognitivism) or neuroscience (neuroaesthetics[74]).

Truth in beauty and mathematics

[edit]Mathematical considerations, such as symmetry and complexity, are used for analysis in theoretical aesthetics. This is different from the aesthetic considerations of applied aesthetics used in the study of mathematical beauty. Aesthetic considerations such as symmetry and simplicity are used in areas of philosophy, such as ethics and theoretical physics and cosmology to define truth, outside of empirical considerations. Beauty and Truth have been argued to be nearly synonymous,[75] as reflected in the statement "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" in the poem "Ode on a Grecian Urn" by John Keats, or by the Hindu motto "Satyam Shivam Sundaram" (Satya (Truth) is Shiva (God), and Shiva is Sundaram (Beautiful)). The fact that judgments of beauty and judgments of truth both are influenced by processing fluency, which is the ease with which information can be processed, has been presented as an explanation for why beauty is sometimes equated with truth.[76] Recent research found that people use beauty as an indication for truth in mathematical pattern tasks.[77] However, scientists including the mathematician David Orrell[78] and physicist Marcelo Gleiser[79] have argued that the emphasis on aesthetic criteria such as symmetry is equally capable of leading scientists astray.

Computational approaches

[edit]

Computational approaches to aesthetics emerged amid efforts to use computer science methods "to predict, convey, and evoke emotional response to a piece of art.[80] In this field, aesthetics is not considered to be dependent on taste but is a matter of cognition, and, consequently, learning.[81] In 1928, the mathematician George David Birkhoff created an aesthetic measure as the ratio of order to complexity.[82]

In the 1960s and 1970s, Max Bense, Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake were among the first to analyze links between aesthetics, information processing, and information theory.[83][84][85] Max Bense, for example, built on Birkhoff's aesthetic measure and proposed a similar information theoretic measure , where is the redundancy and the entropy, which assigns higher value to simpler artworks.

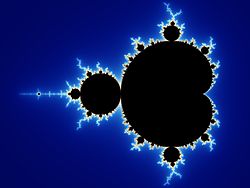

In the 1990s, Jürgen Schmidhuber described an algorithmic theory of beauty. This theory takes the subjectivity of the observer into account and postulates that among several observations classified as comparable by a given subjective observer, the most aesthetically pleasing is the one that is encoded by the shortest description, following the direction of previous approaches.[86][87] Schmidhuber's theory explicitly distinguishes between that which is beautiful and that which is interesting, stating that interestingness corresponds to the first derivative of subjectively perceived beauty. He supposes that every observer continually tries to improve the predictability and compressibility of their observations by identifying regularities like repetition, symmetry, and fractal self-similarity.[88][89][90][91]

Since about 2005, computer scientists have attempted to develop automated methods to infer aesthetic quality of images.[92][93][94][95] Typically, these approaches follow a machine learning approach, where large numbers of manually rated photographs are used to "teach" a computer about what visual properties are of relevance to aesthetic quality. A study by Y. Li and C. J. Hu employed Birkhoff's measurement in their statistical learning approach where order and complexity of an image determined aesthetic value.[96] The image complexity was computed using information theory while the order was determined using fractal compression.[96] There is also the case of the Acquine engine, developed at Penn State University, that rates natural photographs uploaded by users.[97]

There have also been relatively successful attempts with regard to music.[98] Computational approaches have also been attempted in film making as demonstrated by a software model developed by Chitra Dorai and a group of researchers at the IBM T. J. Watson Research Center.[99] The tool predicted aesthetics based on the values of narrative elements.[99] A relation between Max Bense's mathematical formulation of aesthetics in terms of "redundancy" and "complexity" and theories of musical anticipation was offered using the notion of Information Rate.[100]

Evolutionary aesthetics

[edit]Evolutionary aesthetics refers to evolutionary psychology theories in which the basic aesthetic preferences of Homo sapiens are argued to have evolved in order to enhance survival and reproductive success.[101] One example being that humans are argued to find beautiful and prefer landscapes which were good habitats in the ancestral environment. Another example is that body symmetry and proportion are important aspects of physical attractiveness which may be due to this indicating good health during body growth. Evolutionary explanations for aesthetical preferences are important parts of evolutionary musicology, Darwinian literary studies, and the study of the evolution of emotion.

Aesthetic ethics

[edit]Aesthetic ethics refers to the idea that human conduct and behaviour ought to be governed by that which is beautiful and attractive. John Dewey[102] has pointed out that the unity of aesthetics and ethics is in fact reflected in our understanding of behaviour being "fair"—the word having a double meaning of attractive and morally acceptable. More recently, James Page[103] has suggested that aesthetic ethics might be taken to form a philosophical rationale for peace education.

Applied aesthetics

[edit]As well as being applied to art, aesthetics can also be applied to cultural objects, such as crosses or tools. For example, aesthetic coupling between art-objects and medical topics was made by speakers working for the US Information Agency. Art slides were linked to slides of pharmacological data, which improved attention and retention by simultaneous activation of intuitive right brain with rational left.[104] It can also be used in topics as diverse as cartography, mathematics, gastronomy, fashion and website design.[105][106][107][108][109]

Other approaches

[edit]Guy Sircello has pioneered efforts in analytic philosophy to develop a rigorous theory of aesthetics, focusing on the concepts of beauty,[110] love[111] and sublimity.[112] In contrast to romantic theorists, Sircello argued for the objectivity of beauty and formulated a theory of love on that basis.

British philosopher and theorist of conceptual art aesthetics, Peter Osborne, makes the point that "'post-conceptual art' aesthetic does not concern a particular type of contemporary art so much as the historical-ontological condition for the production of contemporary art in general ...".[113] Osborne noted that contemporary art is 'post-conceptual' in a public lecture delivered in 2010.

Gary Tedman has put forward a theory of a subjectless aesthetics derived from Karl Marx's concept of alienation, and Louis Althusser's antihumanism, using elements of Freud's group psychology, defining a concept of the 'aesthetic level of practice'.[114]

Gregory Loewen has suggested that the subject is key in the interaction with the aesthetic object. The work of art serves as a vehicle for the projection of the individual's identity into the world of objects, as well as being the irruptive source of much of what is uncanny in modern life. As well, art is used to memorialize individuated biographies in a manner that allows persons to imagine that they are part of something greater than themselves.[115]

Criticism

[edit]The philosophy of aesthetics as a practice has been criticized by some sociologists and writers of art and society. Raymond Williams, for example, argues that there is no unique and or individual aesthetic object which can be extrapolated from the art world, but rather that there is a continuum of cultural forms and experience of which ordinary speech and experiences may signal as art. By "art" we may frame several artistic "works" or "creations" as so though this reference remains within the institution or special event which creates it and this leaves some works or other possible "art" outside of the frame work, or other interpretations such as other phenomenon which may not be considered as "art".[116]

Pierre Bourdieu disagrees with Kant's idea of the "aesthetic". He argues that Kant's "aesthetic" merely represents an experience that is the product of an elevated class habitus and scholarly leisure as opposed to other possible and equally valid "aesthetic" experiences which lay outside Kant's narrow definition.[117]

Timothy Laurie argues that theories of musical aesthetics "framed entirely in terms of appreciation, contemplation or reflection risk idealizing an implausibly unmotivated listener defined solely through musical objects, rather than seeing them as a person for whom complex intentions and motivations produce variable attractions to cultural objects and practices".[118]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Aesthetic imagination is a creative process that explores the possibilities of aesthetic experience as a free flow of thought not limited to factual reality. It is relevant both to the appreciation and artistic creation of beauty.[35]

- ^ In biology, the term taste has a more narrow meaning limited to the gustatory system.[51]

- ^ Taste is also influenced by a person's upbringing, leading to distinct aesthetic preferences that can reflect their social class.[52]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Slater, B. H., Aesthetics, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Archived 31 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on 15 September 2024.

- ^ Zangwill, Nick. "Aesthetic Judgment Archived 2 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 02-28-2003/10-22-2007. Retrieved 07-24-2008.

- ^ Thomas Munro, "Aesthetics", The World Book Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, ed. A. Richard Harmet, et al., (Chicago, Illinois: Merchandise Mart Plaza, 1986), p. 80.

- ^ Kelly (1998), p. ix.

- ^ Riedel, Tom (Fall 1999). "Review of Encyclopedia of Aesthetics 4 vol. Michael Kelly". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America. 18 (2): 48. doi:10.1086/adx.18.2.27949030.

- ^

- ^

- Audi 1999, pp. 11–12

- Beauchamp 2005, p. 13

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, pp. 17–18

- Robinson 2006, pp. 72–73

- ^

- Audi 1999, pp. 11–12

- Gardner 2003, pp. 231–232

- Fenner 2003, pp. 1–2

- ^ Munro & Scruton 2025, § Three Approaches to Aesthetics

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2025

- ^

- Munro & Scruton 2025, Lead section

- Nanay 2019, p. 4

- Beauchamp 2005, p. 13

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, pp. 17–18

- Robinson 2006, pp. 72–73

- ^

- Stecker 2010, pp. ix

- Nanay 2019, p. 4

- ^

- Audi 1999, pp. 11–12

- Stecker 2010, pp. 1–2

- Herwitz 2008, p. 11

- ^

- Stecker 2010, p. 2

- Herwitz 2008, p. 21–22

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, pp. 17–18

- ^

- Herwitz 2008, p. 21–22

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, pp. 17–18

- Hoad 1993, p. 7

- ^ OED staff 2025

- ^ a b c d e Halliwell 2002, pp. 152–159.

- ^ Poetics, p. I 1447a.

- ^ Poetics, p. IV.

- ^ Halliwell 2002, pp. 152–59.

- ^ Poetics, p. III.

- ^

- Shelley 2022, Lead section, § 2. The Concept of the Aesthetic

- Zangwill 1998, pp. 78–79

- Townsend 2006, pp. 11–12, 17–18, 275

- Shelley 2013, pp. 246–256

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, pp. 16–17

- Townsend 2006, pp. 15–16

- Stecker 2010, pp. 65–69

- Feagin 1999

- ^

- Feagin 1999

- Stecker 2010, pp. 67–68

- ^

- Stecker 2010, pp. 65–69

- Townsend 2006, pp. 17–18

- Focosi 2020

- Feagin 1999

- ^

- Townsend 2006, pp. 15–16

- Feagin 1999

- ^

- Munro & Scruton 2025, § The Aesthetic Object

- Townsend 2006, pp. 11–13

- ^

- Janaway 2005

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, pp. 16–17, 74

- Townsend 2006, pp. 14, 17–18

- Rozzoni 2019

- Plato & Meskin 2023, pp. 95–96

- ^ Slater, § 3. Aesthetic Value

- ^

- Janaway 2005a

- Sartwell 2024, Lead section

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 74

- ^ Lorand 2005, pp. 198–199

- ^

- Janaway 2005a

- Sartwell 2024, Lead section

- ^

- Sartwell 2024, § 1. Objectivity and Subjectivity

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 74

- Janaway 2005

- ^

- Sartwell 2024, § 2. Philosophical Conceptions of Beauty

- De Clercq 2013, pp. 299–301

- ^ Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 15–16

- ^

- Shelley 2022, § 2.4 Aesthetic Experience

- Townsend 2006, pp. 9–11

- Peacocke 2024, Lead section, § 1. Focus of Aesthetic Experience

- ^

- Shelley 2022, § 2.4 Aesthetic Experience

- Townsend 2006, pp. 11–12, 17–18, 275

- ^

- Peacocke 2024, § 2. Mental Aspects of Aesthetic Experience

- Stecker 2010, pp. 40–41, 47, 53–54, 58–59

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 15

- Townsend 2006, pp. 4–6

- Shelley 2022, § 2.3 The Aesthetic Attitude

- ^ Shelley 2022, § 2.3 The Aesthetic Attitude

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 15

- Townsend 2006, pp. 4–6

- Shelley 2022, § 2.3 The Aesthetic Attitude

- ^

- Shelley 2022, § 2.3 The Aesthetic Attitude

- Peacocke 2024, § 1.5 Fundamental Nature

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 15

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 16

- Townsend 2006, pp. 13–14

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 16

- Townsend 2006, p. 5

- Ginsborg 2022, § 2.2 How are Judgments of Beauty Possible?, § 2.3.2 The free play of imagination and understanding

- ^ Townsend 2006, pp. 13–14

- ^ Townsend 2006, pp. 13–14

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 16

- Zangwill 1998, pp. 78–79, 85–86, 90

- ^

- Stecker 2010, pp. 40–41

- Ginsborg 2022, § 2.2 How are Judgments of Beauty Possible?, § 2.3.2 The free play of imagination and understanding

- ^

- Shelley 2022, § 2.2 Aesthetic Judgment

- Bender 1995, p. 379

- ^ Shelley 2022, § 1. The Concept of Taste

- ^ Korsmeyer 2013, p. 258

- ^ Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 678

- ^

- Bunnin & Yu 2004, p. 678

- Tregenza 2005

- Shelley 2022, § 1. The Concept of Taste

- Cohen 2004, pp. 167–170

- Korsmeyer 2013, pp. 257–258

- ^

- Dutton 2013, pp. 267–268

- Sheridan & Gardner 2012, p. 292

- Shockley 2022, pp. 44–46

- ^ Leitch, Vincent B., et al., eds. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001.

- ^ Gaut, Berys; Livingston, Paisley (2003). The Creation of Art. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0521812344.

- ^ a b Gaut and Livingston, p. 6.

- ^ Green, Edward (2005). "Donald Francis Tovey, Aesthetic Realism and the Need for a Philosophic Musicology". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. 36 (2): 227–248. JSTOR 30032170.

- ^ Siegel, Eli (1955). "Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 14 (2): 282–283. JSTOR 425879.

- ^ King, Alexandra. "The Aesthetic Attitude". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Grosswiler, Paul (2010). Transforming McLuhan: Cultural, Critical, and Postmodern Perspectives. Peter Lang Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1433110672. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Danto, Arthur C. (2004). "Kalliphobia in Contemporary Art". Art Journal. 63 (2): 24–35. doi:10.2307/4134518. JSTOR 4134518.

- ^ Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure, André Malraux's Theory of Art (Amsterdam: Netherlands Rodopi, 2009).

- ^ Massumi, Brian (ed.), A Shock to Thought. Expression after Deleuze and Guattari. London, England & New York, New York: Routeledge, 2002. ISBN 0415238048.

- ^ Lyotard, Jean-Françoise, What is Postmodernism?, in The Postmodern Condition, Minnesota and Manchester, 1984.

- ^ Lyotard, Jean-Françoise, "Scriptures: Diffracted Traces", in Theory, Culture and Society, Volume 21, Number 1, 2004.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund, "The Uncanny" (1919). Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Work of Sigmund Freud, 17: 234–236. London, England: The Hogarth Press.

- ^ Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1964), The Visible and the Invisible. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810104571.

- ^ Lacan, Jacques, "The Ethics of Psychoanalysis" (The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book VII), New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1992.

- ^ Kobbert, M. (1986), Kunstpsychologie ("Psychology of art"), Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, Germany.

- ^ Cunningham, Stuart; McGregor, Iain; Weinel, Jonathan; Darby, John; Stockman, Tony (11 October 2023). "Towards a Framework of Aesthetics in Sonic Interaction". Proceedings of the 18th International Audio Mostly Conference. AM '23. New York, New York, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 109–115. doi:10.1145/3616195.3616219. ISBN 979-8-4007-0818-3.

- ^ Thielsch, M. T. (2008), Ästhetik von Websites. Wahrnehmung von Ästhetik und deren Beziehung zu Inhalt, Usability und Persönlichkeitsmerkmalen. ("The aesthetics of websites. Perception of aesthetics and its relation to content, usability, and personality traits."), MV Wissenschaft, Münster, Germany.

- ^ Hassenzahl, M. (2008), Aesthetics in interactive products: Correlates and consequences of beauty. In H.N.J. Schifferstein & P. Hekkert (Eds.): Product Experience. (pp. 287–302). Elsevier, Amsterdam

- ^ Martindale, C. (2007). "Recent trends in the psychological study of aesthetics, creativity, and the arts". Empirical Studies of the Arts. 25 (2): 121–141. doi:10.2190/b637-1041-2635-16nn. S2CID 143506308.

- ^ Ian Stewart. Why Beauty Is Truth: The History of Symmetry, 2008.

- ^ Reber, R.; Schwarz, Norbert; Winkielman, P. (2004). "Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver's processing experience?". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8 (4): 364–382. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3. hdl:1956/594. PMID 15582859. S2CID 1868463.

- ^ Reber, R.; Brun, M.; Mitterndorfer, K. (2008). "The use of heuristics in intuitive mathematical judgment". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 15 (6): 1174–1178. doi:10.3758/pbr.15.6.1174. hdl:1956/2734. PMID 19001586. S2CID 5297500.

- ^ Orrell, David (2012). Truth or Beauty: Science and the Quest for Order. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300186611.

- ^ Gleiser, Marcelo (2010). A Tear at the Edge of Creation: A Radical New Vision for Life in an Imperfect Universe. Free Press. ISBN 978-1439108321.

- ^ Petrosino, Alfredo (2013). Progress in Image Analysis and Processing, ICIAP 2013: Naples, Italy, September 9–13, 2013, Proceedings. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 21. ISBN 978-3642411830.

- ^ Jahanian, Ali (2016). Quantifying Aesthetics of Visual Design Applied to Automatic Design. Cham: Springer. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-3319314853.

- ^ Akiba, Fuminori (2013). "Preface: Natural Computing and Computational Aesthetics". Natural Computing and Beyond. Proceedings in Information and Communications Technology. 6: 117–118. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-54394-7_10. ISBN 978-4431543930.

- ^ Bense, Max (1969). Einführung in die informationstheoretische Ästhetik. Grundlegung und Anwendung in der Texttheorie. Rohwolt.

- ^ A. Moles: Théorie de l'information et perception esthétique, Paris, Denoël, 1973 (Information Theory and aesthetical perception).

- ^ F. Nake (1974). Ästhetik als Informationsverarbeitung. (Aesthetics as information processing). Grundlagen und Anwendungen der Informatik im Bereich ästhetischer Produktion und Kritik. Springer, 1974, ISBN 978-3211812167.

- ^ Schmidhuber, Jürgen (22 October 1997). "Low-Complexity Art". Leonardo. 30 (2): 97–103. doi:10.2307/1576418. JSTOR 1576418. PMID 22845826. S2CID 18741604.

- ^ "Theory of Beauty – Facial Attractiveness – Low-Complexity Art". www.idsia.ch. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Schmidhuber, Jürgen (1991). Curious model-building control systems. International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. Vol. 2. Singapore: IEEE press. pp. 1458–1463. doi:10.1109/IJCNN.1991.170605.

- ^ Jürgen Schmidhuber. Papers on artificial curiosity since 1990: http://www.idsia.ch/~juergen/interest.html, Archived 18 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Schmidhuber, Jürgen (2006). "Developmental robotics, optimal artificial curiosity, creativity, music, and the fine arts". Connection Science. 18 (2): 173–187. Bibcode:2006ConSc..18..173S. doi:10.1080/09540090600768658. S2CID 2923356.

- ^ "Schmidhuber's theory of beauty and curiosity in a German TV show" (in German). Br-online.de. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008.

- ^ Datta, R.; Joshi, D.; Li, J.; Wang, J. (2006). "Computer Vision – ECCV 2006". Europ. Conf. on Computer Vision. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3953. Springer. pp. 288–301. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.81.5178. doi:10.1007/11744078_23. ISBN 978-3540338369.

- ^ Wong, L.-K.; Low, K.-L. (2009). "Saliency-enhanced image aesthetic classification". International Conference on Image Processing. International Conference on Image Processing. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2009.5413825.

- ^ Wu, Y.; Bauckhage, C.; Thurau, C. (2010). "2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition". Int. Conf. on Pattern Recognition. IEEE. pp. 1586–1589. doi:10.1109/ICPR.2010.392. ISBN 978-1424475421.

- ^ Faria, J.; Bagley, S.; Rueger, S.; Breckon, T.P. (2013). "Challenges of Finding Aesthetically Pleasing Images" (PDF). Proc. International Workshop on Image and Audio Analysis for Multimedia Interactive Services. IEEE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ a b Chio, Cecilia Di; Brabazon, Anthony; Ebner, Marc; Farooq, Muddassar; Fink, Andreas; Grahl, Jörn; Greenfield, Gary; Machado, Penousal; O'Neill, Michael (2010). Applications of Evolutionary Computation: EvoApplications 2010: EvoCOMNET, EvoENVIRONMENT, EvoFIN, EvoMUSART, and EvoTRANSLOG, Istanbul, Turkey, April 7–9, 2010, Proceedings. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 302. ISBN 978-3642122415.

- ^ "Aesthetic Quality Inference Engine – Instant Impersonal Assessment of Photos". Penn State University. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Manaris, B., Roos, P., Penousal, M., Krehbiel, D., Pellicoro, L. and Romero, J.; A Corpus-Based Hybrid Approach to Music Analysis and Composition; Proceedings of 22nd Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-07); Vancouver, British Columbia; pp. 839–845. 2007.

- ^ a b Hammoud, Riad (2007). Interactive Video: Algorithms and Technologies. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 162. ISBN 978-3540332145.

- ^ Dubnov, S.; Musical Information Dynamics as Models of Auditory Anticipation; in Machine Audition: Principles, Algorithms and Systems, Ed. W. Weng, IGI Global publication, 2010.

- ^ Shimura, Arthur P.; Palmer, Stephen E. (2012). Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 279.

- ^ Dewey, John; James Tufts (1932). "Ethics". In Jo-Ann Boydston (ed.). The Collected Works of John Dewey, 1882–1953. Carbonsdale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 275.

- ^

- Peace Education – Exploring Ethical and Philosophical Foundations Archived 29 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine infoagepub.com

- Page, James S. (2017). Peace Education : Exploring Ethical and Philosophical Foundations. Information Age Pub. ISBN 978-1593118891. Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2017 – via eprints.qut.edu.au.

- ^ Giannini, A. J. (December 1993). "Tangential symbols: using visual symbolization to teach pharmacological principles of drug addiction to international audiences". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 33 (12): 1139–1146. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03913.x. PMID 7510314. S2CID 32304779.

- ^ Kent, Alexander (2019). "Maps, Materiality and Tactile Aesthetics". The Cartographic Journal. 56 (1): 1–3. Bibcode:2019CartJ..56....1K. doi:10.1080/00087041.2019.1601932.

- ^ Kent, Alexander (2005). "Aesthetics: A Lost Cause in Cartographic Theory?". The Cartographic Journal. 42 (2): 182–188. Bibcode:2005CartJ..42..182K. doi:10.1179/000870405X61487. S2CID 129910488.

- ^ Moshagen, M.; Thielsch, M. T. (2010). "Facets of visual aesthetics". International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 68 (10): 689–709. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2010.05.006. S2CID 205266500. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Visual Aesthetics. Interaction-design.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Lavie, T.; Tractinsky, N. (2004). "Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of web sites". International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 60 (3): 269–298. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2003.09.002. S2CID 205265682.

- ^ Guy Sircello, A New Theory of Beauty. Princeton Essays on the Arts, 1. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- ^ Guy Sircello, Love and Beauty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- ^ Guy Sircello, "How Is a Theory of the Sublime Possible?" The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Autumn, 1993), pp. 541–550.

- ^ Peter Osborne, Anywhere Or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art, Verso Books, London, England, 2013. pp. 3 & 51.

- ^ Tedman, G. (2012), Aesthetics & Alienation, Zero Books.

- ^ Gregory Loewen, Aesthetic Subjectivity, 2011, pp. 36–37, 157, 238.

- ^ Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford University Press, 1977), p. 155. ISBN 978-0198760610.

- ^ Pierre Bourdieu, "Postscript", in Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (London, England: Routledge, 1984), pp. 485–500. ISBN 978-0674212770; and David Harris, "Leisure and Higher Education", in Tony Blackshaw, ed., Routledge Handbook of Leisure Studies (London, England: Routledge, 2013), p. 403. ISBN 978-1136495588 and books.google.com/books?id=gc2_zubEovgC&pg=PT403.

- ^ Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2). doi:10.5130/csr.v20i2.4149.

Sources

[edit]- Aristotle. "Poetics". classics.mit.edu. The Internet Classics Archive. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Audi, Robert (1999). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-07417-2.

- Beauchamp, Tom L. (2005). "Aesthetics, Problems of". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Bender, John W. (1995). "General but Defeasible Reasons in Aesthetic Evaluation: The Particularist/Generalist Dispute". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 53 (4): 379–392. doi:10.2307/430973.

- Bunnin, Nicholas; Yu, Jiyuan (2004). The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-0679-4.

- Cohen, Ted (2004). "The Philosophy of Taste: Thoughts on the Idea". In Kivy, Peter (ed.). The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 167–173. ISBN 978-0-470-75655-3.

- De Clercq, Rafael (2013). "29. Beauty". In Gaut, Berys; McIver Lopes, Dominic (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 299–308. ISBN 978-0-415-78286-9.

- Dutton, Denis (2013). "26. Aesthetic Universals". In Gaut, Berys; McIver Lopes, Dominic (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 267–277. ISBN 978-0-415-78286-9.

- Feagin, Susan L. (1999). "Aesthetic Property". In Audi, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-511-07417-2.

- Fenner, David E. W. (2003). Introducing Aesthetics. Praeger Publisher. ISBN 0-275-97907-5.

- Focosi, Filippo (2020). "Aesthetic Properties". International Lexico of Aesthetics. doi:10.7413/18258630076.

- Gardner, Sebastian (2003). "Aesthetics". In Bunnin, Nicholas; Tsui-James, Eric (eds.). The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 231–256. ISBN 0-631-21907-2.

- Ginsborg, Hannah (2022). "Kant's Aesthetics and Teleology". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 27 June 2025.

- Halliwell, Stephen (2002). "Inside and Outside the Work of Art". The Aesthetics of Mimesis: Ancient Texts and Modern Problems. Princeton University Press. pp. 152–159. ISBN 978-0-691-09258-4.

- HarperCollins (2022). "Aesthetics". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 20 June 2025.

- Herwitz, Daniel (2008). Aesthetics: Key Concepts in Philosophy. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8264-3294-0.

- Hoad, T. F. (1993). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283098-8.

- Janaway, C. (2005). "Value, aesthetic". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 941. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Janaway, C. (2005a). "Beauty". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Korsmeyer, Carolyn (2013). "25. Taste". In Gaut, Berys; McIver Lopes, Dominic (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 257–266. ISBN 978-0-415-78286-9.

- Lorand, Ruth (2005). "Beauty and Ugliness". In Horowitz, Maryanne Cline (ed.). New Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Thomson Gale. pp. 198–205. ISBN 0-684-31377-4.

- Merriam-Webster (2025). "Definition of Aesthetic". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 20 June 2025.

- Munro, Thomas; Scruton, Roger (2025). "Aesthetics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 19 June 2025.

- Nanay, Bence (2019). Aesthetics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-256125-1.

- OED staff (2025). "Aesthetics, n." Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Peacocke, Antonia (2024). "Aesthetic Experience". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 June 2025.

- Plato, Levno; Meskin, Aaron (2023). "Aesthetic Value". In Maggino, Filomena (ed.). Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-3-031-17298-4.

- Robinson, Jenefer (2006). "Aesthetics, Problems of". In Borchert, Donald M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 1 (2 ed.). Macmillan. pp. 72–81. ISBN 978-0-02-865781-3.

- Rozzoni, Claudio (2019). "Aesthetic Value". International Lexico of Aesthetics. doi:10.7413/18258630067.

- Sartwell, Crispin (2024). "Beauty". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- Shelley, James (2013). "24. The Aesthetic". In Gaut, Berys; McIver Lopes, Dominic (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 246–256. ISBN 978-0-415-78286-9.

- Shelley, James (2022). "The Concept of the Aesthetic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 20 June 2025.

- Sheridan, Kimberly M.; Gardner, Howard (2012). "Artistic Development: The Three Essential Spheres". In Shimamura, Arthur P.; Palmer, Stephen E. (eds.). Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience. Oxford University Press. pp. 276–298. ISBN 978-0-19-973214-2.

- Shockley, Paul R. (2022). "Theism and Universal Signatures of the Arts". In Coppenger, Mark; Elkins, William E.; Stark, Richard H. (eds.). Apologetical Aesthetics. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 44–56. ISBN 978-1-6667-1508-8.

- Slater, Barry Hartley. "Aesthetics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 19 June 2025.

- Stecker, Robert (2010). Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art: An Introduction. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4422-0128-6.

- Townsend, Dabney (2006). Historical Dictionary of Aesthetics. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-8108-6483-2.

- Tregenza, Bergeth (2005). "Taste". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 909. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Zangwill, Nick (1998). "The Concept of the Aesthetic". European Journal of Philosophy. 6 (1): 78–93. doi:10.1111/1468-0378.00051.

External links

[edit]- "Aesthetics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Aesthetics in Continental Philosophy Archived 1 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Medieval Theories of Aesthetics Archived 18 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- "The Value of Art". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Concept of the Aesthetic Archived 4 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Aesthetics Archived 29 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine entry in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy