Ancient Egypt in the Western imagination

The culture of Ancient Egypt has fascinated outsiders from its own day well into our own, long after that culture was subsumed first by Greco-Roman, then Christian, then Muslim currents. And while the concept of the "Western world" owes its origin to Christian writers of early medieval Europe and Asia Minor,[1] those same writers were keen to imagine themselves as part of—or heirs to—a cultural continuum that began with classical antiquity and evolved to include the Biblical history of the Jews.

In Western cultures' collective imaginings, the idea of "Ancient Egypt" has developed and changed over millennia no less than those cultures themselves changed. From classical and late antiquity through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and into the modern era, this imagined "Egypt" has served as a powerful symbol, variously representing profound antiquity, esoteric wisdom, evil, the exotic, or timeless grandeur.[2]

An essential factor in Ancient Egypt's enduring mystery and remoteness was that its written languages remained unreadable from about the 5th century CE until the early 19th century, which rendered its own recorded history inaccessible. The continuing engagement of nations and societies that constitute "the West" with Egypt has shaped their art, literature, architecture, philosophy, and popular culture. This influence in turn reflects those societies' contemporary intellectual currents,[3] colonial ambitions, and religious and spiritual ideas in addition to—or instead of—an understanding grounded in historical fact.[2]

A journal dedicated to the subject, named Aegyptiaca Journal of the History of Reception of Ancient Egypt, began publication in 2017 at the University of Munich. The journal covers the influences of ideas about Egypt in Western cultural history across various fields and periods.[4]

According to the conventional periodization of European history,[5] imaginings of ancient Egypt evolved in the following ways:

Classical Greece

[edit]To a Greek observer of the ancient classical age (c. 510 – 323 CE), Egypt was already "ancient" and mysterious.

Herodotus, in his Histories, Book II, gives a detailed if selectively coloured and imaginative description of ancient Egypt. He praises peasants' preservation of history through oral tradition, and Egyptians' piety. He lists the many animals to which Egypt is home, including the mythical phoenix and winged serpent, and gives inaccurate descriptions of the hippopotamus and horned viper. While Herodotus was quite critical about the stories he heard from the priests (II,123).

The Hellenistic Period

[edit]The Hellenistic period (roughly 323 BCE to 31 BCE) fundamentally reshaped the "Western" (Greek) intellectual engagement with Ancient Egypt. Following Alexander the Great's conquest and the subsequent establishment of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt, Greeks were no longer mere visitors but became the ruling elite. This unprecedented proximity and political dominance led to a complex interplay of admiration, adaptation, and intellectual appropriation. Greek scholars, philosophers, and administrators in Alexandria and other Greek cities in Egypt found themselves directly confronting a civilization far older than their own. This encounter inspired in the Greeks a conception of Egypt as an ancient and enduring source of religious wisdom and exotic spectacle, even as Greek culture maintained its own distinct identity and asserted its new political supremacy.

Jewish views of Egypt in antiquity

[edit]The Jewish perception of Egypt in classical antiquity was shaped by the Jews' unique historical and theological narratives, and was very different from the predominantly admiring or pragmatic views of the Greeks and Romans. For Jews, Egypt was defined by the foundational story of the Exodus: a land of slavery, oppression, and locus of divine liberation. However, as large and influential Jewish communities emerged in Egypt itself, particularly in Alexandria, a more complex and sometimes contradictory set of views developed, balancing the ancient memory of bondage with the realities of diasporic life and intellectual engagement with the Gentiles.

Egypt is mentioned 611 times in the Bible, between Genesis 12:10 and Revelation 11:8.[6] The first Greek translation of Hebrew scriptures, the Septuagint, was commissioned in Alexandria in the 3rd century CE.

Roman Empire

[edit]Among the Romans, an Egypt that had been drawn into their economic and political sphere was still a source of wonders: Ex Africa semper aliquid novi;[7][page needed][a] the exotic fauna of the Nile is embodied in the famous "Nilotic" mosaic from Praeneste, and Romanized iconographies were developed for the "Alexandrian Triad": Isis, who developed a widespread Roman following; Harpocrates, "god of silence";[8] and the Ptolemaic syncretic deity Serapis.[9]

The Roman perception of Ancient Egypt was deeply influenced by that of Rome's Hellenistic precursors, but evolved significantly with Rome's increasing political and economic dominance. From the late Republic's (c. 509 – 27 BCE) strategic engagement with the Ptolemies to the Empire's direct annexation and administration of Roman Egypt in 30 BCE as an essential imperial province, Roman intellectuals and the broader populace viewed Egypt through a multifaceted lens. It was simultaneously the indispensable granary of the empire, a land of ancient and often bewildering wisdom, and an inexhaustible source of exotic spectacle that both fascinated and occasionally repulsed Roman sensibilities.

Early Christianity and the Desert Fathers of Egypt

[edit]The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics who lived primarily in the Wadi El Natrun, then known as Skete, in Roman Egypt, beginning around the third century.

Later Roman Empire

[edit]The Later Roman Empire (284—642) saw the rise of Christianity from a persecuted sect to the state religion; as conceptualized by thinkers in later centuries, events would establish both the pagan Greco-Roman world and the monotheistic Hebrews as ancestors of the "Western world".[10][page needed][b]

Division into east and west

[edit]Between 285 CE and 380 CE, the Roman Empire saw major political and religious transformations, beginning with Emperor Diocletian's strategic division of imperial rule into eastern and western halves in 285 CE. Constantine the Great founded the new imperial capital Constantinople in 330 CE, further solidifying the empire's dual structure, and re-orienting its power center to the east.

Egypt was part of the eastern provinces and, after the fragmentation of the western empire, remained under the control of Constantinople; it was a vital source of grain and revenue, closely tied to the administrative and economic structures of the capitol.

Christianity as state religion

[edit]Amidst these political changes, Christianity continued its spread, finding converts in the elite as well as the masses, and among the populations who lived on the fringes or outside of the empire, notably in the tribes of Germanic peoples. The pivotal moment arrived in 313 CE when Emperors Constantine and Licinius issued a decree granting widespread religious toleration, effectively ending state-sponsored persecution. In 380 CE, Emperor Theodosius I formally established Nicene Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire.

Christian Egypt

[edit]The establishment of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire would also mean that Christians began to adopt Jewish views of Egypt as a land of particular evil, as well their own intolerance towards all things pagan in general.

Egypt—especially Alexandria—was a major center of both early Christianity and the early established Christian church, as well home to a substantial population of largely Hellenized Jews.

Egyptian Christians of the late Roman Empire abhorred the religion and culture of Ancient Egypt. While general Christian opposition to paganism targeted Greco-Roman deities and temples (and people; see, for example, Hypatia and Serapeum of Alexandria), Egyptian Christianity developed a distinct antagonism toward those native Egyptian religious practices still active in some regions and to the totality of its pre-Christian culture and history.

Temples to gods like Isis, Horus, and Thoth were denounced as demonic, and Christian writers often portrayed Pharaonic religion as not only false but particularly deceptive, occult in nature, or simply evil and demonic. Egyptian hieroglyphs and iconography of the Ancient Egyptian religion were associated with witchcraft and idolatry. Anti-paganism policies of the early Byzantine Empire caused the defacement, repurposing, or destruction of artwork, monuments, and temples. The Philae temple complex—among others—was eventually closed by imperial order in the late 4th and early 5th centuries.

Still, some aspects of ancient Egyptian culture were absorbed or reinterpreted. Saints' cults, monastic desert traditions, and architectural elements echoed earlier Egyptian forms, though now fully recontextualized within Christian meaning. The result was a sharp rhetorical rejection of ancient Egyptian religion, even as certain local patterns of devotion and symbolism subtly persisted.

Late antiquity and early Middle Ages

[edit]The period of European history from approximately 500 to 1400–1500 CE is traditionally called the "Middle Ages." The term "Middle Ages" was first used by 15th-century scholars to describe the time between their own era and the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Historians often divide the Middle Ages into periods—typically early and late, or early, central (or high), and late.[5]

The transitional periods of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (through c. 1000 CE) saw the total collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476, a widening cultural and religious gulf between the Greek-speaking east and the Vulgar Latin—then Germanic and Romance-speaking—peoples of the Western Europe. In the continuing empire in the east—known by modern readers as the Byzantine Empire—Arab conquests of its Levantine provinces were a precursor to the Arab conquest of Egypt in 646 CE.

Arab Conquest of Egypt

[edit]The Byzantine Empire—directly impacted by its loss of Egypt—was home to Greek and Coptic-speaking chroniclers such as John of Nikiû (fl. 680 – 690), who wrote the History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria), a document of the events with local detail.

Direct and detailed analysis of the conquest of Egypt itself would remain largely the domain of Eastern Christian and later Muslim historians. The peoples of the new states in the former western empire had a much more limited and indirect understanding of the event.

Middle Ages

[edit]During the High Middle Ages (c. 1000 – c. 1300 CE), the Latin West's view of Egypt, as expressed in manuscripts by its clergy, was a complex blend of ancient biblical narratives, a veneration of its monastic heritage, and a nascent, often hostile, awareness of its contemporary reality as a powerful Muslim realm. Direct contact was still limited, making symbolic and historical interpretations paramount.

In Medieval Europe, Egypt was depicted primarily in the illustration and interpretation of the biblical accounts. These illustrations were often quite fanciful, as the iconography and style of ancient Egyptian art, architecture and costume were largely unknown in the West (illustration, right). Dramatic settings of the Finding of Moses, the Plagues of Egypt, the Parting of the Red Sea and the story of Joseph in Egypt, and from the New Testament the Flight into Egypt often figured in medieval illuminated manuscripts. Biblical hermeneutics were primarily theological in nature, and had little to do with historical investigations. Throughout the Middle Ages "Mummia", made—if genuine, by pounding exhumed[by whom?]mummified bodies—was a standard product of apothecary shops.[11]

Renaissance and Enlightenment

[edit]German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) gave an allegorical "decipherment" of hieroglyphs through which Egypt was thought of as a source of ancient mystic or occult wisdom. In alchemist circles, the prestige of "Egyptians" rose. A few scholars, however, remained skeptical:[12] in the 16th century, Isaac Casaubon determined that the Corpus Hermeticum of the great Hermes Trismegistus was actually a Greek work of about the 4th century CE (even though Casaubon's work was also criticized by Ralph Cudworth).

18th century

[edit]

Early in the 18th century, Jean Terrasson had written Life of Sethos, a work of fiction, which launched the notion of Egyptian mysteries. In an atmosphere of antiquarian interest, a sense arose that ancient knowledge was somehow embodied in Egyptian monuments and lore. Egyptian imagery pervaded the European Freemasonry of the time and its imagery, such as the eye on the pyramid. Contemporaneously, the Great Seal of the United States (1782), which appears on the United States one-dollar bill also features this imagery. There are Egyptian references in Mozart's Masonic-themed[citation needed] Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute, 1791), and his earlier unfinished "Thamos".[citation needed]

The revival of curiosity about the Antique world, seen through written documents, spurred the publication of a collection of Greek texts that had been assembled in Late Antiquity, which were published as the corpus of works of Hermes Trismegistus. But the broken ruins that sometimes appeared in paintings of the episode of the Rest on the Flight into Egypt were always of Roman character.

With historicism came the first fictions set in the Egypt of the imagination. Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra had been set partly in Alexandria, but its protagonists were noble and universal, and Shakespeare had not been concerned to evoke local color.

19th century

[edit]

The rationale for what is known as "Egyptomania" rests on a similar concept: Westerners looked to ancient Egyptian motifs because ancient Egypt itself was intrinsically so alluring. The Egyptians used to consider their religion and their government somewhat eternal; they were supported in this thought by the enduring aspect of great public monuments which lasted forever and which appeared to resist the effects of time. Their legislators had judged that this moral impression would contribute to the stability of their empire.[c]

The culture of Romanticism embraced every exotic locale, and its rise in the popular imagination coincided with Napoleon's failed Egyptian campaign and the start of modern Egyptology, beginning very much as a competitive enterprise between Britain and France. A modern "Battle of the Nile" could hardly fail to stir renewed curiosity about Egypt beyond the figure of Cleopatra. At about the same moment, the tarot was brought to Europe's attention by the Frenchman Antoine Court de Gebelin as a purported key to the occult knowledge of Egypt. All this gave rise to "Egyptomania" and occult tarot.

This legendary Egypt has been difficult, but not impossible to reconcile with the 1824 decryption of hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion. Inscriptions that a century earlier had been thought to hold occult wisdom, proved to be nothing more than royal names and titles, funerary formulae, boastful accounts of military campaigns, even though there remains an obscure part that might agree with the mystic vision. The explosion of new knowledge about actual Egyptian religion, wisdom and philosophy has been widely interpreted as exposing the mythical image of Egypt as an illusion that had been created by the Greek and Western imaginations.

In art, the development of Orientalism and the increased possibility of travel produced a large number of depictions, of varying degrees of accuracy. By the late 19th-century, exotic and carefully studied or researched decor was often dominant in depictions of both landscape and human figures, whether ancient or modern.[13][page needed]

One of the most enduring literary treatments of ancient Egypt to come out of the 19th-century Romantic movement is Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Ozymandias" (1818).

Egyptian Revival architecture extended the repertory of classical design explored by the Neoclassical movement and widened the decorative vocabulary that could be drawn upon.

The well-known Egyptian veneration of the dead and beliefs about the afterlife inspired Highgate Cemetery in London (1839); its themed features included a 'Gothic Catacomb' as well as an 'Egyptian Avenue'.[14]

In 1842, the American Joseph Smith published The Book of Abraham, a foundational text of his new Latter-Day Saint movement. Smith claimed it was a translation of ancient Egyptian papyri acquired from a traveling exhibition of Egyptian mummies that he attended in 1835. Smith also claimed that the Book of Mormon is translated from a hieratic-like script that he called "Reformed Egyptian".

In music, Ancient Egypt was the setting for the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi's (1813–1901) opera Aida, commissioned by the Khedive (sultan) of Ottoman Egypt for premiere in Cairo in 1871.

The 1895 historical novel Pharaoh, by Polish author Bolesław Prus, portrayed the demise of Egypt's New Kingdom.

20th century

[edit]

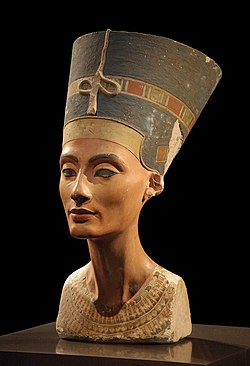

In 1912 the discovery of a well-preserved painted limestone bust of Nefertiti, unearthed from its sculptor's workshop near the royal city of Amarna, sparked new interest in ancient Egypt. The bust, now in Berlin's Egyptian Museum, became well known throughout the world through photographs. Nefertiti's strong-featured profile had a notable influence on feminine beauty ideals of the 20th century.[15]

British architectural historian James Stevens Curl (b. 1937) published work on the Egyptian motifs of Highgate cemetery.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art resurrected the Temple of Dendur within its own quarters in 1978. In 1989, the Louvre raised its own glass pyramid.

Egypt in popular culture

[edit]

The 1922 discovery of the undamaged tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun revived public interest in ancient Egypt; the treasures of "King Tut" influenced popular fashion and design, particularly Art Deco.[16] The discovery also led to sensational claims, promoted by the tabloid press, of a 'curse' that killed the discoverers. These claims were dismissed by Howard Carter.[17]

Agatha Christie's 1924 short story "The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb" from her collection Poirot Investigates features mysterious deaths that occur during an archaeological excavation.[18] A popular "curse of the mummy" myth developed out the tabloid reporting on Tutankhamun's excavators, which in turn inspired the horror film The Mummy with Boris Karloff. Cinema, and later television (see below), has proven to be one of the most powerful and enduring forms of imagining and re-imagining Ancient Egypt since the medium's invention.

In 1993 Las Vegas's Luxor Hotel opened with its replica tomb of Tutankhamun.

In 1978, American comedian Steve Martin recorded the novelty song "King Tut". A 1986 hit song and music video by American rock band The Bangles called "Walk Like an Egyptian" evoked poses from the mural art of ancient Egypt.

Egypt in cinema

[edit]Hollywood's depictions of ancient Egypt are major contributors to the fantasy Egypt of contemporary popular culture. Karloff's memorable performance as "the Mummy" in his 1932 established the cinematic trope of ancient Egyptian mummies reanimating as undead monsters. The 1944 American horror film The Mummy's Curse was one of many that made use of this enduring undead antagonist.

Cleopatra was a successful 1934 American epic film directed by Cecil B. deMille with starlet Claudette Colbert in the title role. DeMille's epic The Ten Commandments was a blockbuster of 1956; Jeanne Crain as Nefertiti in Queen of the Nile (1961) followed, then the Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor vehicle Cleopatra (1963). And in 1966, the 1895 novel Pharaoh was adapted into a Polish feature film.[19]

The popular science-fiction/action franchise Stargate, in which Egyptian gods are actually malevolent aliens, premiered as a film in 1994. A best-selling series of novels by French author and Egyptologist Christian Jacq, inspired by the life of Pharaoh Ramses II ("the Great"), had its first release in 1995. A remake of the 1932 Boris Karloff film, also called The Mummy, was released in 1999 and led to its own media franchise.

21st century

[edit]HBO's miniseries Rome features several episodes set in Greco-Roman Egypt. A faithful but anachronistic stage set of a court of Pharaonic Egypt (as opposed to the historically correct Hellenistic period) was built in Rome's Cinecittà studios. The series depicts intrigues between Cleopatra, Ptolemy XIII, Julius Caesar, and Mark Antony.

La Reine Soleil, a 2007 animated film by Philippe Leclerc set in the tumultuous 18th Dynasty (c. 1550 – 1292 BCE), portrays Akhenaten, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun), Akhesa (later Ankhesenamun), Nefertiti, and Horemheb in a complex struggle pitting the priests of Amun against Akhenaten's strict monotheistic innovations.

A second remake of the The Mummy was released in 2017. Fantastical representations of Egypt continue to feature in music videos and other products of Western popular culture of the 21st century.[20]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ ex Africa semper aliquid novi '[There is] always something new [coming] out of Africa', Pliny the Elder (c. 24 - 79 CE), Naturalis Historia, 8, 42 (unde etiam vulgare Graeciae dictum semper aliquid novi Africam adferre), a translation of the Greek «Ἀεὶ Λιβύη φέρει τι καινόν».

- ^ Rémi Brague states that "Western culture, which influenced the whole world, came from Europe. But its roots are not there. They are in Athens and Jerusalem... The Roman attitude senses its own incompleteness and recognizes the call to borrow from what went before it. Historically, it has led the West to borrow from the great traditions of Jerusalem and Athens: primarily the Jewish and Christian tradition, on the one hand, and the classical Greek tradition on the other." [10][page needed]

- ^ Reprinted in Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac, Fourier et Napoleon: l'Egypte et les cent jours: memoires et documents inedits, Paris, Firmin Didot Freres, 1844, p. 170.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Quigley 1979, p. 84.

- ^ a b Versluys 2018, pp. 159–166.

- ^ Peres 2019.

- ^ Budka, España-Rivera & Ebeling 2024.

- ^ a b Barzun & Parker 2025.

- ^ Strong 2001, p. 221-222.

- ^ Versluys 2015.

- ^ "Harpocrates" at The British Museum.

- ^ "Serapis" at The British Museum.

- ^ a b Brague 2009.

- ^ "Mummy" at Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Findlen 2004, p. 38.

- ^ Thompson 2015, p. 255.

- ^ Curl 1972, p. 86-102.

- ^ Tharoor 2012.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 326.

- ^ Christie 2016.

- ^ Kasparek 1994, pp. 45–50.

- ^ Rothman 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barzun, Jacques; Parker, Geoffrey (May 16, 2025). "History of Europe". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved June 9, 2025.

- Brague, Rémi (2009). "Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization". philpapers.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- Budka, Julia; España-Rivera, Mariana; Ebeling, Florian, eds. (31 December 2024). "About the Journal". Aegyptiaca. Journal of the History of Reception of Ancient Egypt. University Library Heidelberg. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- Christie, Agatha (2016) [1924]. Poirot Investigates. HarperCollins Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-0-00-816483-6.

- Curl, James Stevens (1972). The Victorian Celebration of Death. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5446-9.

- Findlen, Paula, ed. (2004). Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. Routledge.

- "Harpocrates". The British Museum. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- Kasparek, Christopher (1994). "Prus' Pharaoh: the Creation of a Historical Novel". The Polish Review (1): 45–50.

- "Mummy". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- Peres, Tessa (August 13, 2019). "Mummy Issues – How Ancient Egypt Shaped Sigmund Freud". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved June 10, 2025.

- Quigley, Carroll (1979). The Evolution of Civilizations – An Introduction to Historical Analysis. Liberty Fund, Inc. Retrieved June 8, 2025.

- Rothman, Lily (21 February 2014). "There's a Very Good Reason Why Katy Perry's "Dark Horse" Video Is Set in Ancient Egypt". Time. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- "Serapis". The British Museum. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- Strong, James (2001). Strong's Expanded Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Thomas Nelson Publishers. ISBN 0-7852-4540-5.

- Tharoor, Ishaan (6 December 2012). "The Bust of Nefertiti: Remembering Ancient Egypt's Famous Queen". Time. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- Thompson, Jason (2015). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology 1: From Antiquity to 1881. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-599-3.

- Versluys, Miguel John (2015). Aegyptiaca Romana: Nilotic Scenes and the Roman Views of Egypt. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. Vol. 144. Brill.

- Versluys, Miguel John (2018). ""Une géographie intérieure": The Perpetual Presence of Egypt". Aegyptiaca. Journal of the History of Reception of Ancient Egypt (3): 159–166. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- Winstone, H.V.F. (2006). Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Barzan, Manchester. ISBN 1-905521-04-9. OCLC 828501310.

Further reading

[edit]- Assmann, Jan (1997). Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-58738-3.

- Baines, John (2013). High Culture and Experience in Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

- Baines, John, ed. (2019). Historical Consciousness and the Use of the Past in the Ancient World. Oxford University Press.

- Bentley, J. H. (June 1996). "Cross-Cultural Interaction and Periodization in World History". American Historical Review: 749–770.

- Benton, Janetta Rebold; DiYanni, Robert (1998). Arts and Culture: An Introduction to the Humanities. Prentice Hall PTR.

- Besserman, Lawrence, ed. (1996). The Challenge of Periodization: Old Paradigms and New Perspectives. ISBN 0-8153-2103-1.

- Breasted, James Henry (1967). A History of Egypt from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, with Illustrations and Maps. New York: Bantam Books.

- Colla, Elliott (2008). Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity (PDF). Duke University Press.

- Curl, James Stevens (2005). The Egyptian Revival (revised and enlarged ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36118-4.

- Dobson, Eleanor; Tonks, Nichola, eds. (2020). Ancient Egypt in the Modern Imagination. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fazzini, Richard A. (1988). "Pharaonic Art and the Modern Imagination". The UNESCO Courier. XLI (9): 33–35. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- Herodotus (2003). Marincola, John M.; Radice, Betty (eds.). The Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- Ickow, Sara (2012). "Egyptian Revival". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- Joseph, Celucien L. (August 2014). "Anténor Firmin, the 'Egyptian Question,' and Afrocentric Imagination" (PDF). The Journal of Pan African Studies. 7 (2): 127–176. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- Moser, Stephanie (2006). Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum. University of Chicago Press.

- Nyord, Rune (2020). Yearning for Immortality: The European Invention of the Ancient Egyptian Afterlife. University of Chicago Press.

- Spier, Jeffrey; Cole, Sara E., eds. (2022). Egypt and the Classical World: Cross-Cultural Encounters in Antiquity. J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Tromans, Nicholas; et al. (2008). The Lure of the East, British Orientalist Painting. Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85437-733-3.

- Villing, Alexandra (2022). "Mediterranean Encounters: Greeks, Carians, and Egyptians in the First Millennium BC". In Spier, Jeffrey; Cole, Sara E. (eds.). Egypt and the Classical World. J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

External links

[edit]- Aegyptiaca. Journal of the History of Reception of Ancient Egypt, published by the University of Munich Faculty for the Study of Culture, Egyptology and Coptic Studies.