History of political Catalanism

The history of Catalan political nationalism, also referred to as Catalanism (Catalan: catalanisme), traces its origins to the early years of the Bourbon Restoration in Spain following the failure of the federalist system of the short-lived First Spanish Republic. However, its roots extend to the first half of the 19th century, driven by the cultural revival movement known as the Renaixença and opposition to the centralist model of the liberal Spanish state. Historian John H. Elliott notes that the term "Catalanism," previously associated with cultural movements, began to take on significant political meaning during the Revolutionary Sexennium (1868–1874).[1] Specifically, the term "Catalanist" emerged around 1870–1871, used by members of Jove Catalunya and the journal La Renaixensa to signify ambitions beyond mere regionalism.[2] As a political movement, Catalanism solidified in the late 1880s.[3]

Origins of Political Catalanism (1808–1875)

[edit]Dual Catalan and Spanish Identity and Opposition to Centralist Liberal State

[edit]

According to historian Pere Anguera, around 1800, Spain was primarily an "administrative reference" for many Catalans, not a source of collective identity. Distinctive elements, from the Catalan language to civil law traditions, sustained a particular Catalan consciousness, further reinforced by an idealized memory of lost liberties.[4] In 1775, English traveler Henry Swinburne noted the Catalans' "passionate enthusiasm for liberty," citing their numerous insurrections and describing the War of the Spanish Succession as a fierce struggle for freedom. Similarly, French general Jacques Dugommier, upon entering Catalonia in 1794 during the War of the Convention, reported to the Committee of Public Safety that Catalans were "enemies of the Spanish" and cherished liberty.[5] However, historian Angel Smith observes that Catalan elites began embracing the Spanish project from the 1770s, with a significant shift during the Peninsular War against Napoleon.[6]

A sense of Spanish identity emerged in Catalonia during the Peninsular War, as Catalans, for the first time, shared a common enemy with other Spaniards.[7][8] Smith notes that the emotional term pàtria (transl. homeland) was commonly used to refer to both Spain and Catalonia.[9]

Yet, opposition to Castilian linguistic and legal dominance persisted, as Catalans continued to advocate for their abolished institutions and laws of the Principality of Catalonia, abolished under the Decree of Nueva Planta of Catalonia of 1714, and maintained the use of Catalan in administrative and academic contexts despite decrees mandating Spanish.[10] Catalans rejected not Spain as a whole, but Castile's attempts to dominate it.[11] French traveler Alexandre de Laborde and Spanish general Evaristo San Miguel noted this animosity toward Castile.[12][13]

In the 1808 pamphlet Centinela contra franceses, Barcelona native Antonio de Capmany praised Spain's diversity as a strength against Napoleonic invasion, contrasting it with France's uniformity.[14] However, he viewed Catalan as a "dead provincial language" for literary purposes.[15] Similarly, liberal Antonio Puigblanch argued in 1811 that Catalonia should abandon Catalan for Spanish to integrate fully into the nation.[16]

During the construction of Spain's liberal state, Catalan liberals emphasized the continuity between historical Catalan liberties and the new constitutional regime to foster integration into liberal Spain while reinforcing Catalan identity.[17] In 1808, the Superior Junta of Catalonia urged deputies to the Cortes of Cádiz to preserve Catalonia's traditional privileges if uniform legislation proved unfeasible.[18] During the Liberal Triennium (1820), the Provincial Deputation of Catalonia claimed to inherit the spirit of Catalan ancestors in defending civil liberties.[17]

This period saw the emergence of a dual Catalan-Spanish identity, encapsulated in the phrase "Spain is the nation, Catalonia is the homeland."[19][20] The newspaper El Nuevo Vapor in 1836 highlighted Catalans' pride in belonging to Spain while emphasizing their attachment to Catalonia.[21] Catalanist priest Jaume Collell later attributed this dual identity to the Peninsular War, noting both unprecedented Spanish unity and a strong regional particularism.[22] Anguera similarly observes that the war fostered solidarity with Spain while proving Catalans' self-reliance.[23]

The first Catalan-language newspaper, Lo verdader catalá,[24] advocated preserving Catalan identity alongside Spanish unity while criticizing the centralist state model of the Moderate Party.[25] Progressive liberal Tomás Bertran i Soler even proposed restoring Catalonia's historical constitution, akin to Basque privileges.[26]

In 1851, J.B. Guardiola advocated for decentralization as the best guarantee of Spain’s unity, viewing Spain not as a single nation but as a collection of nations. Three years later, following the success of the Vicalvarada, Víctor Balaguer launched the newspaper La Corona de Aragón, which championed decentralization. An editorial declared its title a “gauntlet thrown at despots and tyrants” who sought to enslave Catalonia, whether from a throne or a ministerial chair. The paper, accused by some of being a “flag of independence,” argued that Spain comprised several kingdoms distinguished by race, language, and history. In 1855, Juan Illas Vidal lamented in his pamphlet Cataluña en España that Catalonia and Castile, once distinct nationalities, had not been united by time and justice. Joan Mañé i Flaquer, a leading ideologue of Catalonia’s conservative bourgeoisie, echoed this sentiment, noting the lack of shared feelings and aspirations among “brother peoples,” which he attributed to the Castilianizing uniformity imposed by Isabeline governments. In 1860, Juan Cortada y Sala’s book Cataluña y los catalanes distinguished Catalans from other Spaniards while considering them “brothers,” proposing a cohesive Spain. He also noted a group of Catalans with “exaggerated patriotic zeal” seeking to revive ancient administrations aligned with the free spirit of the Principality of Catalonia.[25] That same year, Antonio de Bofarull wrote:[25]

Spain, as I have argued elsewhere, is not a nation but a collection of nationalities, each with its own history and glory, unknown to the others. This ignorance leads to the dominance of the one that has absorbed all importance.

In March 1866, seven Catalan deputies led by Manuel Duran y Bas of the Liberal Union proposed a bill in the Congress of Deputies for broad administrative decentralization, transferring powers from the central government to provinces grouped into a new territorial division. They argued against uniformity imposed in the name of unity.[27] The Minister of the Interior, José Posada Herrera, from the same party, opposed what he termed “excentralization,” calling it “an enemy of liberty” that would lead to “horrible local tyrannies.” He questioned whether all people under one government should be governed by the same law, arguing that Duran’s system would create inequalities.[28] Madrid’s press attacked the proposal, labeling the Catalan deputies “regional deputies” and threatening tariff reforms to harm Catalonia. The bill was rejected, with 44 votes in favor (including all Catalan deputies) and 88 against.[28]

Renaixença and Popular Catalanism

[edit]

The Renaixença, or Catalan Romanticism, was a cultural movement aimed at restoring the Catalan language to its prestigious status, as it had remained vibrant in popular literature.[29] Its beginning is traditionally dated to August 1833, with the publication of Buenaventura Carlos Aribau’s Oda a la Patria in El Vapor.[29] This was followed by 27 Catalan poems by Joaquín Rubió y Ors, published in the Diario de Barcelona from 1839, later compiled in Lo Gayter del Llobregat under his pseudonym. In the introduction, Rubió outlined his literary program, emphasizing love for “the things of one’s homeland” and defending the Catalan language, which was “sadly fading day by day” and shamed by some.[30] He wrote:

Catalonia can still aspire to independence—not political, as it weighs too little compared to other nations with vast armies and navies, but literary, beyond the reach of political balance.[30]

The movement focused on literature, particularly poetry, with a milestone being the first Jocs Florals held in 1859, organized by the Barcelona City Council. An earlier precedent was a 1841 poetry contest by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Barcelona, where Rubió won for a poem on the almogavars and Braulio Foz for a historical essay on the Compromise of Caspe.[31] The Jocs Florals, with awards for faith, homeland, and love, promoted historicist poetry, and their ceremonial speeches became a platform for regionalism, attracting diverse audiences. They “fanned the flame of Catalan identity while proclaiming Catalonia’s Spanishness.”[32]

However, Enric Prat de la Riba, a key Catalan nationalist, later criticized Jocs Florals participants for lamenting the Catalan language’s decline while speaking Castilian at home and ignoring Catalonia outside the contests.[33] Most early Renaixença figures, except the progressive liberal Víctor Balaguer, aligned with Moderantismo. Rubió, known for conservative works like El libro de las niñas (1845) and Manual de elocuencia sagrada (1852), defended Catholic universities as barriers against error.[33] Antonio de Bofarull, also conservative, wrote the first Catalan serial novel, L’orfeneta de Menargues o Catalunya agonisant (1862).[33]

Alongside the Renaixença, Catalan historiography revived, beginning in 1836 with Félix Torres Amat’s Memorias para ayudar a formar un diccionario crítico de escritores catalanes and Próspero de Bofarull y Mascaró’s Los condes de Barcelona vindicados.[35] In 1839, Pablo Piferrer’s Recuerdos y bellezas de España passionately recounted the “glorious eras of the Raimundos and Jaimes,” praising those who defended their homeland’s freedoms.[35] Historian Josep Fontana credits it as the first work to outline Catalonia’s national history, including milestones like September 11.[36][37]

Later historians included Víctor Balaguer, with Bellezas de la historia de Cataluña (1853) and Historia de Cataluña y de la corona de Aragón (1860), aiming for a united yet confederated Spain, and Antonio de Bofarull, who edited medieval Catalan chronicles and began Historia crítica (civil y eclesiástica) de Cataluña in 1876.[38] Jaume Vicens Vives noted that Balaguer’s work inspired patriotic poets, while Bofarull’s supported jurists and politicians.[39]

In 1863, Barcelona’s City Council tasked Balaguer with naming streets for the city’s Eixample district, blending Catalan regionalist and Spanish nationalist imagery. North-south streets honored historical institutions (e.g., Corts Catalanes, Diputació del General), while east-west streets commemorated battles, writers, and heroes (e.g., Balmes, Aribau, Roger de Lauria).[40][41]

In his 1868 Jocs Florals inaugural speech, months before the Glorious Revolution, Balaguer declared Spain a “great nation composed of several nationalities,” with Castilian as the language of the lips and Catalan as the language of the heart, enriching Spain with dual literatures.[42]

Democratic-republican currents in Catalonia, left of Progressivism, used Catalan to reach popular sectors, advocating for el català que ara es parla (the Catalan spoken now) over the archaic Catalan of the Jocs Florals.[43] Frederic Soler (Serafí Pitarra) satirized revered figures like James I of Aragon in his 1856 play Don Jaume el Conqueridor, performed privately, followed by public works like La Esquella de la Torratxa (1860).[44]

Democratic Sexennium: Federalism’s Failure

[edit]

After the Glorious Revolution of 1868, Catalan symbols and heroes of 1714 were celebrated, with calls to restore laws abolished by the Nueva Planta Decrees. The journal Lo Gay Saber proclaimed it was “time to regenerate Catalonia,” denouncing the “bastonazos” of Castilianization.[45]

While monarchists like Balaguer supported a “monarchical federation,” republicans championed Federalism. On May 18, 1869, representatives of the Federal Democratic Republican Party from Catalonia, Valencia, Aragon, and the Balearic Islands signed the Tortosa Federal Pact, stating:[47]

The citizens here agree that the three ancient provinces of Aragon, Catalonia, and Valencia, including the Balearic Islands, are united for the conduct of the republican party and the revolutionary cause, without implying any intent to separate from the rest of Spain.

In 1869, conservative Francesc Romaní Puigdendolas published El federalismo en España, defending federalism as Spain’s traditional system—a “bundle of nationalities, united but not merged.”[48][49] Josep Narcís Roca Farreras proposed ending “absorbent, centralizing, uniform” unity to modernize Spain, distinguishing Catalonia’s “defensive, fraternal” nationalism from Castile’s “aggressive, domineering” one.[49]

In 1870, Jove Catalunya, the first patriotic Catalanist association, was founded, adopting a Mazzinian name but opposing Italian unification principles.[50] Members included Pere Aldavert, Àngel Guimerà, and Lluís Domènech i Montaner. They launched La Gramalla, replaced in 1871 by La Renaixensa.[51] Initially featuring political articles by Roca Farreras, it later focused on literary criticism and historical research under Guimerà.[52] Jove Catalunya pioneered combining literature with anticastilianist politics, using the term “Catalanist.”[3]

Catalan Carlists, inspired by Basque counterparts, defended the abolished Fueros in 1872’s Los catalans y sos furs.[53] Carlist pretender Carlos VII promised to restore Catalonia’s constitutions.[54]

On February 11, 1873, after Amadeo I of Spain’s abdication, the First Spanish Republic was proclaimed. Barcelona’s republican newspaper La Campana de Gracia celebrated in Catalan:

We have it! The throne has fallen forever in Spain. There will be no other king but the people, nor any government but the just, holy, and noble federal republic.[55]

On March 9, 1873, federalists, backed by workers, attempted to proclaim a Catalan State, prompting President Estanislao Figueras to visit Barcelona to urge patience until parliamentary approval.[53] Valentí Almirall relaunched El Estado Catalán in Madrid to push for a federal republic.[55] The Cantonal Rebellion of July 1873 had limited support in Catalonia due to Carlist threats, leading to the Republic’s collapse and the Bourbon Restoration in Spain.[56][57]

Birth of Political Catalanism (1875–1905)

[edit]Historian John H. Elliott notes that the 1868–1874 Sexennium’s failure was pivotal in transforming Catalan cultural regionalism into political nationalism.[58]

Valentí Almirall and the Centre Català

[edit]

The 1875 Bourbon Restoration curtailed freedoms, forcing nascent political Catalanism to retreat. La Renaixensa faced suspensions despite its cultural focus, becoming a daily in 1881 under Pere Aldavert and Àngel Guimerà.[36] Groups like the Catalanist Association for Scientific Excursions, founded in 1876, promoted Catalonia’s “splendor and glory” through publications and conferences.[36] A 1878 split birthed the Catalan Excursions Association.[59]

After the Republic’s failure, Valentí Almirall led a Catalanist shift within federal republicanism, breaking with Francesc Pi i Margall. In 1879, he founded Diari Catalá, the first all-Catalan daily, which closed in 1881.[60][61] In 1880, he convened the First Catalanist Congress,[60] leading to the 1882 creation of the Centre Català, a platform for promoting Catalanism and pressuring the government.[62][63][64]

In 1882, protests in Barcelona against a French trade treaty saw demonstrators wearing barretinas and senyera-colored ties, met with police dispersal and cries of “Long live Catalonia!”[65] In 1885, the Centre Català presented a Memorial of Grievances to King Alfonso XII, bypassing Parliament, denouncing trade treaties and civil code unification.[66] It concluded:

The only just and suitable path is to abandon absorption and embrace true liberty, seeking harmony through equality and variety, ensuring perfect union among Spain’s regions.[67]

In 1886, Almirall published Lo catalanisme, articulating Catalan “particularism” and advocating for recognizing regional personalities shaped by history, geography, and character. He proposed a dual structure like Austria-Hungary, viewing Catalonia as positivist and democratic against Castile’s idealistic dominance.[61][69] His French essay L’Espagne telle qu’elle est blamed Spain’s woes on Castilian authoritarianism.[70]

Gaspar Núñez de Arce criticized Almirall’s Catalanism, warning it threatened Spain’s unity.[71] Almirall countered that he sought not to break Spain but to end its Castilian identification, using Castilian “with reluctance” due to its imposition.[72] Joan Mañé i Flaquer wrote in Diario de Barcelona:

Do you consider us brothers? Treat us as equals, not imposing your laws and language, as we do not impose ours. If you see us as a conquered land, do not expect fraternal reciprocation.[72]

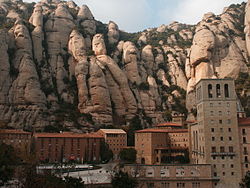

Catalan symbols emerged: the flag (1880), hymn (1882), September 11 (1886), dance (1892), and patrons Saint George (1885) and Virgin of Montserrat (1881).[73][74][75] Castells spread beyond Camp de Tarragona, symbolizing Catalan vitality.[76]

Lliga de Catalunya, Unió Catalanista, and Bases de Manresa (1887–1892)

[edit]In 1887, the Centre Català split between Almirall’s federalist faction and a conservative group around La Renaixensa.[77] The latter published Los Fueros de Cataluña (1878) by José Coroleu and José Pella Forgas, defining the Catalan nation as Catalan-speaking peoples, including Roussillon, Valencia, and Mallorca. It proposed a conservative, estate-based system, reserving public offices for native Catalans.[78]

The conservative faction formed the Lliga de Catalunya in November 1887, joined by the Centre Escolar Catalanista, including future leaders Enric Prat de la Riba, Francesc Cambó, and Josep Puig i Cadafalch.[79] During the 1888 Jocs Florals and the Barcelona Universal Exposition (1888), they presented a Message to the Queen Regent, demanding free Catalan Cortes, official use of Catalan, and a Catalan supreme court.[80]

Conservative Catalanist figures like Josep Torras i Bages, who wrote La Tradició Catalana (1892), emphasized Catalonia’s Catholic identity against liberal uniformity.[81] Jaume Collell, a vigatanismo leader, won the 1888 Jocs Florals with Sagramental, ambiguously proclaiming a “free Catalonia within the Spanish kingdom.”[82]

The conservative shift redefined Catalonia as the nation and Spain as the state.[83] In 1891, Narcís Verdaguer proposed the Unió Catalanista, which held its first assembly in Manresa in March 1892, approving the Bases de Manresa.[84] These 17 articles advocated autonomy, exclusive use of Catalan, native-only public offices, and corporate-elected Cortes, marking the birth of conservative political Catalanism.[85][86]

In 1894, Enric Prat de la Riba and Pere Muntanyola’s Compendi de la Doctrina Catalanista distinguished Catalonia as a “natural” nation from Spain’s “artificial” state.[87][88] Historian John H. Elliott sees this as an attempt to invent Catalonia as a nation.[89]

Angel Smith notes that Catalan nationalism emerged from the conservative right, driven by battles over protectionism and the Civil Code, appealing to urban and rural elites.[90]

Post-1898 Nationalism and the Lliga Regionalista

[edit]

Most Catalanists supported Cuban autonomy as a precedent for Catalonia, but Francesc Cambó’s call for Cuban independence found little support.[91] In 1897, the Unió Catalanista sent a Missatge a S.M. Jordi I, rei dels Hel·lens, celebrating Crete’s annexation to Greece, an act of Catalanist fervor.[92] Prat de la Riba’s anonymous La Question Catalane addressed European press.[93] The Catalanist Teaching Association founded the first Catalan-language school in 1898.[94]

The 1898 Spanish–American War defeat spurred Catalan regionalism, leading to the 1901 formation of the Lliga Regionalista from the Unió Regionalista and a Centre Nacional Català splinter group.[95] After failed collaboration with Francisco Silvela’s conservatives, the Lliga triumphed in Barcelona’s 1901 municipal elections, ending electoral fraud, and won six seats in the 1901 Spanish general election.[96][95] Some members, including Jaime Carner and Lluís Domènech i Montaner, left in 1904 to form the Centre Nacionalista Republicà.[97]

Simultaneously, Alejandro Lerroux’s Lerrouxism, a populist Spanish nationalist movement, gained traction in Barcelona’s working-class districts.[98] In 1903, the Centre Autonomista de Dependents del Comerç i de la Indústria was founded, promoting Catalanism, education, and social reform.[99]

Political Catalanism in Spanish Politics (1905–1923)

[edit]¡Cu-Cut! incident and Solidaritat Catalana

[edit]

On November 25, 1905, officers stormed the offices of the satirical weekly ¡Cu-Cut! in Barcelona over a cartoon mocking Spanish military defeats, also attacking La Veu de Catalunya.[100][101] The liberal government of Eugenio Montero Ríos declared a state of emergency but resigned under pressure from Alfonso XIII, who supported the military.[102][103]

Alejandro Lerroux endorsed the attackers in La Publicidad , calling Catalanism a “degenerate offspring” of romanticism and social unrest.[104] The new government under Segismundo Moret passed the Law of Jurisdictions, transferring crimes against the homeland and army to military courts.[103]

In May 1906, Solidaritat Catalana, a coalition led by Nicolás Salmerón, united republicans, Catalanists, and Carlists against the Law of Jurisdictions.[105] The Lliga distanced itself from romantic Catalanism and the Bases de Manresa.[106]

That month, Enric Prat de la Riba published La nacionalitat catalana, reinforcing Catalonia as a nation within Spain’s state.[97] He envisioned a cultural empire from Lisbon to the Rhône, led by Catalonia.[107]

Solidaritat’s rallies, like the May 20, 1906, event with 200,000 attendees, were massive.[108] In the 1907 Spanish general election, it won 41 of Catalonia’s 44 seats.[109] Francesc Macià was elected, and Enric Prat de la Riba became Barcelona Provincial Council president.[110]

Borja de Riquer notes that Solidaritat transformed Catalan politics, making the “Catalan question” a pressing issue for Madrid.[111] Jordi Canal highlights the Lliga and Francesc Cambó as key beneficiaries.[110]

Solidaritat collapsed over the Lliga’s support for Antonio Maura’s local administration bill and the Tragic Week of 1909.[100] In 1910, progressive Catalanists formed the Federal Nationalist Republican Union, which lasted until 1917, when many joined the Catalan Republican Party.[100]

Canalejas Government and the Commonwealth of Catalonia

[edit]

In 1911, the Barcelona Provincial Council, led by Enric Prat de la Riba, revived a long-standing Catalanist demand, also part of the Solidaritat Catalana coalition's program: uniting Catalonia’s four provincial councils into a single regional entity. On October 16, the four councils jointly approved the Bases de Mancomunitat Catalana, envisioning an assembly of all provincial deputies and a permanent eight-member council, two per province. Six weeks later, the Bases were submitted to Prime Minister José Canalejas, who introduced them to the Spanish Parliament as the Mancomunities Bill on May 1, 1912.[112]

Early in his career, Canalejas had favored a centralized state, once stating that greater local autonomy could yield “nothing good.” By 1910, as prime minister, he had shifted, declaring that “a centralist liberal belongs in paleontology or archaeology.”[113] He aimed to create a regional body, the Commonwealth of Catalonia, integrating the four Catalan provincial councils. Resistance came from within his own Liberal Party, led by Segismundo Moret and supported by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. Canalejas delivered a persuasive parliamentary address to win over Liberal MPs, yet 19, including Moret, voted against the bill.[113] The Congress of Deputies passed it on June 5, 1912, but Canalejas’ Assassination of José Canalejas delayed Senate approval. The law was enacted in December 1913, with the Commonwealth established in April 1914.[114][115]

The four provincial councils transferred their powers to the Commonwealth, but the central government retained its authority, disappointing the Lliga Regionalista. Nevertheless, the Commonwealth demonstrated effective governance despite limited resources, advancing education and culture through technical schools, universities, and libraries like the Institut d’Estudis Catalans and Library of Catalonia. It also developed infrastructure, including roads, telephone networks, and social services, fostering autonomist sentiment across Catalan society.[116]

Symbolically, the Commonwealth unified Catalonia’s provinces, marking the first self-governance since the Nueva Planta decrees. In his April 6, 1914, inaugural speech, Prat de la Riba referenced this, a point the Lliga leveraged to promote Catalanist consciousness and lay the foundation for broader autonomy. The Commonwealth highlighted the Lliga’s pragmatic strategy of deal-making, supporting the central government in exchange for concessions, a tactic later seen in post-Spanish Transition Catalanism. Prat de la Riba governed in Barcelona, while Francesc Cambó led in Madrid, marking the Lliga’s peak influence.[117]

Historian Jordi Canal argues that Prat de la Riba aimed to “build the Catalan nation” through the Commonwealth, focusing on infrastructure and culture as state-like structures.[118] John H. Elliott views the Commonwealth as an ambitious step toward regional revitalization, though constrained by Madrid’s opposition to decentralization that could threaten Spain’s unity.[119]

Per Catalunya i l'Espanya Gran and the 1918–1919 Autonomy Campaign

[edit]From Catalonia, systematically excluded from Spain’s governance, we, labeled as separatists and regionalists, address Spaniards of good faith who seek greater dignity for their land. The obstacle is the exhausting struggle between a dominant nationality and others refusing to vanish. We propose harmonizing Spain’s nationalities with the state, allowing each to govern its internal affairs while contributing to the whole. This will make Spain the vibrant sum of its peoples, whole as created by God, without mutilating their language, culture, or identity. Catalonia’s issue will not be resolved through violence, Kulturkampf, betrayals, or political maneuvering. The only path is full autonomy, paving the way for a federal, great Spain. Persisting otherwise leads to a weaker, divided Spain.

— Manifesto Per Catalunya i l'Espanya Gran, 1916

In March 1916, before the Spanish general election, 1916, the Lliga Regionalista published the manifesto Per Catalunya i l'Espanya Gran, drafted by Prat de la Riba—who died in August 1917—and signed by all Lliga parliamentarians. It condemned Catalonia’s exclusion from Spanish law, relegating it to “third-class Spaniards,” and demanded autonomy to end assimilationist policies, envisioning a unified “peninsular Iberian empire” including Portugal.[120]

In July 1917, amid the 1917 Spanish political crisis, Cambó convened Catalan parliamentarians in Barcelona, though 13 monarchist MPs withdrew. The assembly, including Alejandro Lerroux, affirmed Catalonia’s autonomist aspirations and demanded a federal structure for Spain. They called for constituent Cortes and, if ignored, a 1917 Parliamentary Assembly in Barcelona on July 19.[121][122] The Conservative government of Eduardo Dato dismissed it as “separatist,” and only Lliga, republican, reformist, and socialist MPs attended. The assembly, dissolved by Barcelona’s governor, demanded a sovereign government for constituent elections. After the August 1917 general strike, it reconvened in Madrid on October 30. That day, Cambó secured King Alfonso XIII’s support for a coalition government under Manuel García Prieto, including Lliga’s Joan Ventosa. This collapsed, leading to another coalition under Antonio Maura, with Cambó, lasting until November 1918.[123][124][125][125]

With the assembly and coalitions failing, Cambó declared it “Catalonia’s hour” and launched the Catalan autonomy campaign of 1918–1919, shaking Spanish politics.[126][127] Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points and the post-World War I self-determination principle, the Commonwealth and Catalan MPs in November 1918 petitioned for autonomy, citing the global triumph of peoples’ self-governance.[128]

Initially, King Alfonso XIII backed the autonomy statute to divert Catalan masses from revolution, but Spanish nationalism triggered an anti-Catalan campaign, mobilizing thousands in Madrid and beyond.[129][130] On December 2, Castilian councils in Burgos issued the Message of Castile, defending Spanish unity and opposing regional autonomy, even calling for a boycott of Catalan industries.[131] El Norte de Castilla headlined: “Facing Catalan nationalism, Castile affirms the Spanish nation.” Only Basque and Galician regions showed some support.[132]

The king aligned with Castilian provinces, and in December 1918 parliamentary debates, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora accused Cambó of dual ambitions, while Antonio Maura insisted Catalans were inherently Spanish. The statute, backed by 98% of Catalan municipalities, was rejected, prompting most Catalan parliamentarians to withdraw in protest.[133][134] In Barcelona, Cambó rallied with the slogan “Monarchy? Republic? Catalonia!” prioritizing autonomy over regime type.[135]

Prime Minister Count of Romanones formed an extraparliamentary commission under Maura, which proposed a diluted statute, stripping Commonwealth powers. The Commonwealth’s [130] 1919 Catalan Autonomy Statute was ignored, and despite Catalan MPs’ return to push for a plebiscite, Romanones closed the Cortes on February 27, 1919, amid Barcelona’s La Canadiense strike. Cambó halted the campaign, avoiding civil resistance.[136][137] Historian Albert Balcells notes the Lliga’s support for the Somatén against strikers made civil disobedience untenable, while the Spanish nationalist Unión Monárquica Nacional challenged Lliga’s dominance.[138]

The Lliga’s pro-employer stance during Barcelona’s violent labor conflicts led to a split, with dissenters forming Acció Catalana in 1922, succeeding in 1923 provincial elections. Francesc Macià had earlier left the Lliga, though his influence was still marginal.[139]

Primo de Rivera Dictatorship (1923–1930): Persecution and Resistance

[edit]

Anti-Catalanist Policy and Commonwealth Dissolution

[edit]The Lliga Regionalista initially supported Primo de Rivera’s coup in 1923, trusting his decentralization promises, which quickly faded.[140][141] On coup day, Primo praised Catalan speeches at a Montjuïc furniture exhibition, claiming to be “Catalanized” by affection for Catalonia.[142]

His September 13 manifesto condemned “blatant separatist propaganda,” and five days later, the Primo de Rivera Military Directorate issued a decree punishing “crimes against homeland security and unity” under the 1906 Law of Jurisdictions, banning non-Spanish flags, Catalan in official acts, and requiring local records in Spanish.[143] The policy, under the slogan España una, grande e indivisible, aimed to erase Catalan identity.[144] Nationalist centers were closed, militants jailed, and cultural entities like the Ateneu Barcelonès, Jocs Florals, and FC Barcelona faced restrictions.[145][146] Street names were Castilianized, Catalan advertisements banned, and the sardana La Santa Espina prohibited as a “hymn of hateful ideas.”[140][147]

Education decrees mandated Spanish-only teaching, with inspectors empowered to suspend non-compliant teachers and close schools.[148] The Church faced repression, with priests detained and Bishop Josep Miralles relocated.[149] Over 100 institutions, including Lliga offices and La Veu de Catalunya, were shut down.[140][150]

In March 1924, over 100 Castilian intellectuals, led by Pedro Sáinz Rodríguez, signed a manifesto supporting the Catalan language.[151] High Catalan culture, like Antoni Rovira i Virgili’s Historia Nacional de Catalunya, faced less persecution, with new publishers and 308 Catalan titles by 1930.[143][152]

The Commonwealth of Catalonia was dissolved in 1925, deemed a potential “small state” by Primo.[153][154] Alfonso Sala, a Spanish nationalist, replaced Josep Puig i Cadafalch as Commonwealth president in 1923, but resigned in April 1925 after its powers were curtailed.[155][156] Historian Genoveva García Queipo de Llano notes Primo’s policies alienated Catalan society broadly.[157]

Resistance and Catalanist Revival: Catalunya endins

[edit]

The Barcelona Bar Association resisted, refusing to publish its Guía Judicial in Spanish. After two years, the dictatorship forcibly replaced its board in March 1926, exiling members, though they returned soon after.[158][159] On June 19, 1925, FC Barcelona fans booed the Marcha Real at a match, resulting in a six-month stadium closure and the exile of president Hans Gamper.[145]

Acció Catalana presented a manifesto to the League of Nations in Geneva, demanding an autonomy referendum, with limited impact.[160] The Catalan Church, led by Francisco Vidal y Barraquer, resisted Spanish-only liturgy, becoming a defender of regional freedoms.[161][162]

Private initiatives fueled a cultural revival, with ateneus, choirs, and religious groups fostering Catalan identity under the slogan Catalunya endins (‘Catalonia inward’), strengthening internal resilience.[163][164]

-

Their demolition under Primo’s orders.

-

Rebuilt in 2011 near their original site.

-

The columns today, viewed from Montjuïc Palace.

Opposition and the Prats de Molló Plot

[edit]

The dictatorship banned nationalist parties. Acció Catalana’s moderate leader Jaume Bofill i Mates exiled himself to Paris, with Lluís Nicolau d'Olwer taking charge. A radical faction led by Antoni Rovira i Virgili split, launching La Nau in 1927, later forming Acció Republicana de Catalunya.[165]

Estat Català, led by Francesc Macià, pursued armed resistance. In 1925, it raised funds through the Pau Claris loan and stockpiled weapons near the French-Spanish border.[166] Macià sought Soviet support in Moscow but received none.[167]A failed Garraf plot targeted the royals’ train in June 1925.[167] In 1926, Macià planned an invasion from Prats de Molló with escamots. Betrayed by Italian double agent Riciotti Garibaldi, French police arrested over 100 in November. Macià, tried in Paris in 1927, was exiled to Belgium.[167]The plot gained international attention, elevating Macià’s status as "l'Avi" (the Grandpa) and l'Avi boosting propaganda. In 1928, Macià’s Latin American tour culminated in Cuba, hosting the Catalan Separatist Assembly, forming the Partit Separatista and drafting a Provisional Catalan Constitution, based on liberal democratic and progressive principles. After a failed 1929 coup, he shifted to internal insurrection.[168]

Second Spanish Republic and Civil War (1931–1939)

[edit]Proclamation of the Catalan Republic and Generalitat Restoration

[edit]

In March 1931, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya formed, becoming the dominant force in Catalonia during the Second Spanish Republic, shifting Catalanism leftward.[169] It united Estat Català under Francesc Macià, Partit Republicà Català led by Lluís Companys, and the Grup de L’Opinió. Macià’s charisma drove Esquerra’s landslide in the 1931 Spanish local elections, winning 25 seats in Barcelona.[170]

On April 14, 1931, Companys proclaimed the Republic from Barcelona’s City Hall balcony, raising the Spanish Republican flag. An hour later, Macià, with the senyera, declared “the Catalan State,” to integrate into the “Federation of Iberian Republics.”[171] From the Barcelona Provincial Council balcony, he announced assuming governance, stating, “they’ll only remove us dead.” His manifesto proclaimed a “Catalan Republic” within an “Iberian Confederation.”[172] Macià appointed Companys as Barcelona’s civil governor and formed a government dominated by Esquerra, excluding the Lliga Regionalista.

Later, referencing the Pact of San Sebastián, Macià declared “the Catalan Republic as part of the Iberian Federation.”[173] His actions aimed to force autonomy per the San Sebastián agreement, not independence.[174]

The Provisional Government of the Second Republic sent three ministers Marcelino Domingo, Lluis Nicolau d'Olwer, and Fernando de los Ríos. On April 17, Esquerra renounced the Catalan Republic for a commitment to present a Catalan autonomy statute and recognition of the Generalitat of Catalonia, reviving the institution abolished in 1714. The Generalitat assumed provincial functions and organized a municipal assembly until elections.[175][171] Most parties except Estat Català and the Workers and Peasants’ Bloc accepted.[174]

On April 26, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora was warmly received in Barcelona. A decree legalized Catalan in schools, but tension arose when the Generalitat’s May 3 decree clashed with central powers.[174][176]

1932 Autonomy Statute

[edit]

The Generalitat convened municipalities to elect a 45-member Provisional Generalitat Council. Esquerra dominated due to the Lliga Regionalista’s withdrawal. On June 9, a commission drafted the Nuria Statute, finalized by June 20 and approved in a referendum with 99% support and 75% turnout.[177][171] In Barcelona, 175,000 voted yes, 2,127 no.[178] Macià presented it to Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, who submitted it to the Constituent Cortes on August 18.[174]

The Nuria Statute proposed a federal state, exceeding the 1931 Spanish Constitution’s unitary framework, claiming Catalan citizenship and sole Catalan officiality.[179][180] From January to April 1932, the Cortes revised it, angering nationalists.[181] Opposition came from liberals like Miguel de Unamuno, republicans, and socialists, with traditionalists mobilizing protests.[182][183]

The Sanjurjada coup in August 1932 hastened approval on September 9, with 314 votes for and 24 against.[181][171] Alcalá-Zamora signed it on September 15. Manuel Azaña’s support balanced autonomy with Spanish unity.[183]

The statute disappointed nationalists, removing references to sovereignty, mandating Spanish co-officiality, and limiting Generalitat powers. Slow transfers and underfunding fueled frustration, yet it was a practical tool for Catalan legislation.[184][185]

In November 1932, Esquerra Republicana, allied with Unió Socialista, won the regional elections, followed (but far) by the Regionalist League. Francesc Macià led until his 1933 death, succeeded by Lluís Companys with a left-wing coalition.[186][187] In January 1934, Esquerra-led coalitions won most municipalities, with Carles Pi i Sunyer as Barcelona’s mayor.[188]

Conflict over the Crop Contracts Law and the October 1934 Revolution

[edit]On March 21, 1934, the Parliament of Catalonia unanimously passed the Crop Contracts Law, with deputies from the Lliga Catalana, formerly the Lliga Regionalista, absent. The law secured tenant farmers, known as rabassaires, the right to cultivate leased land for at least six years and to acquire ownership of plots they had farmed continuously for over 18 years.[189][190]

The law faced strong opposition from the Catalan Agricultural Institute of Saint Isidore, representing major landowners, and the Lliga, which urged the Radical Republican Party government under Ricardo Samper, supported by the Lliga and CEDA, to challenge the law before the Constitutional Guarantees Court. On May 4, the government filed the appeal, alleging the law infringed on state powers. This exposed the Lliga's prioritization of economic interests over autonomy, contradicting its 1933 pledge for broader self-governance.[190][189][191]

On June 8, 1934, the court, by a 13–10 vote, declared the Catalan Parliament incompetent on the matter, nullifying the law. In response, Catalonia's Parliament passed an almost identical law on June 12, triggering a severe political crisis between Madrid and Barcelona. Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya deputies, joined by Basque Nationalist Party members in solidarity, withdrew from the Spanish Cortes. The crisis fueled nationalist sentiment, boosting paramilitary activities and separatist propaganda by the Joventuts d'Esquerra Republicana-Estat Català, led by Josep Dencàs. The Communist Party of Catalonia demanded the "unlimited right of the Catalan nation to self-determination, up to complete separation from the oppressive Spanish state."[189][192][190]

To avoid further confrontation, representatives of both governments negotiated amendments to the law's regulations during the summer. However, the agreement between Samper and Lluís Companys collapsed when a new government under Alejandro Lerroux, including three CEDA ministers, formed in Madrid in early October. This sparked the October 1934 Revolution, with Companys proclaiming the Catalan State within a Spanish Federal Republic.[193]

On October 6, 1934, at around 8 p.m., following a revolutionary general strike called by the Workers' Alliance, Companys announced the Generalitat's break with the "corrupted" Republic's institutions, denouncing the "monarchist and fascist forces" that had seized power. He proposed a provisional Republican government based in Barcelona. However, this act was not aligned with the ongoing workers' revolution, as the Generalitat refused to arm revolutionaries and even acted against them. Companys' move aimed to curb a social revolution, maintain ERC's control over agrarian unions, and respond to pressure from Marxist and independentist groups.[194][191][195][196][197]

The rebellion lacked planning, despite Josep Dencàs mobilizing the escamots and Mossos d'Esquadra. The CNT's passivity and the intervention of the Spanish Army, led by General Domingo Batet, ended the revolt by October 7. Batet's restrained approach limited casualties to eight soldiers and 38 civilians. He later received the Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand.[195][198]

Companys and most Generalitat ministers were imprisoned, except Dencàs, who escaped. The Catalan Statute of Autonomy of 1932 was suspended, and all autonomous institutions were replaced by military control. On January 2, 1935, the Cortes indefinitely suspended the Statute, with the right demanding its permanent repeal. The Lliga joined the government-appointed Generalitat Council, reinforcing its image as an opponent of autonomy, though it later challenged the January 1935 law before the Constitutional Guarantees Court. A repressive wave followed, closing political and union centers, suppressing newspapers, dismissing town councils, and detaining thousands. In June 1935, Companys was sentenced to 30 years for rebellion.[194][199][197][200]

Victory for the Front d'Esquerres and Generalitat Restoration

[edit]In the February 1936 elections, the Popular Front triumphed, forming a left-republican government under Manuel Azaña. Its first act was to grant amnesty to those convicted in the October 1934 Revolution, fulfilling a key campaign promise.[201]

The amnesty freed Generalitat government members, and a March 1 decree restored the Catalan Parliament and reinstated Lluís Companys as president. This met the primary demand of the Front d'Esquerres de Catalunya, Catalonia's Popular Front, which won 59% of the vote, aided by the CNT's decision not to advocate abstention. The warm reception of the freed leaders across Spain reflected growing support for regional autonomy. In Barcelona, Companys was hailed as a hero, becoming an iconic figure in Catalan nationalism alongside Francesc Macià. His famous words upon return were: "We will fight again, suffer again, and triumph again."[201][202][200][203]

The Generalitat's Executive Council, in agreement with the central government, began implementing the Crop Contracts Law. Nationalist rhetoric intensified, with Manuel Carrasco i Formiguera of Democratic Union of Catalonia advocating for Catalonia as an independent state, and Joan Comorera of Socialist Union of Catalonia calling for a Socialist Catalan Republic federated with Iberian socialist republics.[201][204]

Spanish Civil War

[edit]The failure of the July 1936 coup in Barcelona shifted power to workers' organizations, primarily the CNT-AIT. Lluís Companys negotiated with the CNT to form the Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia, theoretically under the Generalitat but effectively holding real power. This created a dual power structure, resolved on September 26 when the Militias Committee dissolved, and anarchists, alongside PSUC and POUM, joined the Generalitat government led by Josep Tarradellas. Estat Català was excluded due to tensions with the CNT and ERC. The Lliga Regionalista, despite not supporting the coup, backed the Nationalist side due to the social revolution and persecution of its members.[205][206]

A November 1936 plot, allegedly led by Estat Català's Joan Torres Picart, aimed to replace Companys with Parliament President Joan Casanovas to declare Catalan independence under French or British protection. Its veracity was disputed, and Casanovas remained Parliament President.[207]

The Generalitat expanded its powers, controlling public order, the economy, justice, and defense, functioning as a near-independent state for the war's first ten months. The May Days of 1937 and the Republican government's relocation to Barcelona in October 1937 shifted dynamics. On May 3, 1937, the Generalitat's attempt to retake the CNT-controlled Telefónica building in Barcelona sparked clashes involving the CNT, POUM, PSUC, and Generalitat forces. The Republican government sent 5,000 mossos d'esquadra, and anarchist ministers called for a ceasefire. By May 7, order was restored, but the Generalitat lost control over public order and defense to the new Republican government under Juan Negrín. Companys focused on cultural Catalanization and propaganda.[208][209][210]

Negrín's centralization efforts, justified by war needs, included moving the government to Barcelona after losing the Cantabrian front. Tensions rose as the Republic assumed control over justice, war industries, and defense. The Generalitat's autonomy waned, lowering Catalan morale. Companys and Basque lehendakari José Antonio Aguirre sought French and British mediation to end the war while preserving their statutes, but failed.[211][212][213]

On April 5, 1938, Franco's forces occupied Lleida and abolished the Catalan Statute of Autonomy of 1932, enforcing a unified Spanish identity. After the Battle of the Ebro, Franco launched the Catalonia Offensive on December 23, 1938. By January 26, 1939, Barcelona fell with little resistance, followed by Girona on February 5. Republican leaders, including Azaña, fled to France, followed by a massive exodus. By February 11, Catalonia was fully under Francoist control. Antoni Rovira i Virgili vowed to preserve Catalan identity in exile, while Gaziel lamented the loss of Catalan institutions.[214][213][215][216]

Francoist Dictatorship (1939–1975)

[edit]Repression and Exile

[edit]

Franco's victory led to the exile of Catalan Republican leaders and intellectuals, depleting Catalonia's leadership. Lluís Companys was arrested by the Gestapo in August 1940, handed over to Francoist authorities, tortured, and executed at Montjuïc Castle on October 15, 1940, declaring "Per Catalunya!" before dying.[217][214][218]

Francoist repression in Catalonia was brutal, driven by vengeance and a determination to eradicate Catalan identity. Over 4,000 were executed between 1938 and 1953, with widespread purges, imprisonments, and humiliations targeting ERC, CNT, and leftists. The regime sought to eliminate Catalan distinctiveness, banning the Catalan language in public life, purging cultural institutions, and renaming streets and towns in Spanish. This "cultural genocide," as termed by Josep Benet, was endorsed by figures like Ramón Serrano Suñer, who called Catalans "morally and politically sick."[219][220][221]

Despite repression, Catalan culture survived clandestinely through private patronage, with books printed covertly and institutions like the Institute of Catalan Studies operating underground. This resilience prevented complete cultural annihilation, as even conservative Catalans supported cultural recovery.[222]

Resistance in the 1940s and 1950s

[edit]Most Catalan parties, except the Lliga Regionalista, opposed the dictatorship. Estat Català formed the National Front of Catalonia in 1940, collaborating with Allies during World War II. In exile, Companys attempted to form a Catalan government but failed due to tensions between ERC and PSUC. A National Council of Catalonia was established, adopting independentist stances. After the Allied victory in 1945, hopes of intervention against Franco faded, limiting exile efforts.[223][217]

In 1947, the Montserrat Monastery hosted a major resistance event during the enthronement of the Virgin of Montserrat, attended by over 60,000 people under a clandestine Catalan flag, marking a cultural defiance against Francoism. The 1951 Barcelona tram boycott was another significant protest, though lacking nationalist focus.[224][225]

In 1954, Josep Irla resigned as exiled Generalitat president, and Josep Tarradellas was elected but declined to form a government. Resistance shifted to legal cultural associations, which organized literary contests and conferences. The 1958–1959 Galinsoga affair campaign, led by Cristians Catalans, forced the resignation of La Vanguardia Española's Francoist director for anti-Catalan remarks.[226][227]

Political Catalanism Revival (1960–1975)

[edit]

The 1960 Palau de la Música events, where attendees sang the banned Cant de la Senyera during a Francoist event, marked the revival of political Catalanism. Jordi Pujol, accused of organizing the protest, was imprisoned for three years. Cultural initiatives like Serra d'Or, Òmnium Cultural, and Edicions 62 bolstered Catalan identity. The 1963 statements by Montserrat's abbot Aureli Escarré criticizing Franco led to his exile. Campaigns like Volem bisbes catalans and Català a l'escola reinforced linguistic demands.[228][229][230]

The 1966 La Capuchinada saw students and intellectuals demand cultural rights, leading to the Taula Rodona and the 1969 Coordinadora de Forces Polítiques de Catalunya, uniting opposition groups. The 1970 Burgos trials protest at Montserrat and the 1971 Assembly of Catalonia consolidated anti-Francoist and nationalist demands under the slogan Llibertat, amnistia, estatut d'autonomia. The Assemblea mobilized widespread support, challenging the regime openly.[231][232][233]

Reign of Juan Carlos I (1975–2014)

[edit]Democratic Transition and Generalitat Restoration (1975–1978)

[edit]

After Franco's death in November 1975, the Assembly of Catalonia intensified its campaign for freedom, amnesty, and autonomy. The 1976 Avui newspaper and the Marxa de la Llibertat reflected growing freedoms. The first post-war September 11 celebration in 1976 drew over 100,000 in Sant Boi de Llobregat. The 1977 elections saw leftist victories in Catalonia, with the Partit Socialista de Catalunya-Congrés and PSUC leading. The Asamblea de Parlamentarios demanded the restoration of the 1932 Statute. Josep Tarradellas returned on October 23, 1977, as Generalitat president, forming a unity government. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 recognized Catalonia as a "nationality," approved by 90% of Catalan voters.[234][235][236][237]

1979 Statute and Jordi Pujol's Governments (1980–2003)

[edit]

The Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 1979 was drafted in 1978 and approved in a 1979 referendum with 88.1% support, despite low turnout (59.6%). It granted less autonomy than the 1932 Statute in some areas but expanded others. CiU, led by Jordi Pujol, won the 1980 elections and governed until 2003, focusing on "nation-building" through linguistic and cultural policies, including the 1983 and 1998 Linguistic Normalization Laws. Pujol's policies aimed to strengthen Catalan identity, though they sparked tensions over bilingualism.[238][239][240]

Tripartit Government (2003–2010) and 2006 Statute

[edit]

In 2003, the PSC, ERC, and ICV formed a left-wing "tripartit" government under Pasqual Maragall. The Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, approved in 2005 by the Catalan Parliament, declared Catalonia a "nation" and expanded autonomy. After contentious negotiations, it was revised by the Spanish Cortes and approved in a 2006 referendum, despite opposition from ERC and the PP. Infrastructure crises in 2007 and the PP's constitutional challenge fueled nationalist demands, culminating in the 2009 La dignidad de Cataluña editorial. José Montilla led the tripartit from 2006 to 2010.[241][242][243][244]

Growth of Catalan Independentism and the Process Toward the November 9, 2014 Consultation

[edit]

In late June 2010, after four years of deliberation amid intense political pressure, the Constitutional Court of Spain issued its ruling on the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, significantly undermining key nationalist aspirations.[245] The decision invalidated provisions recognizing Catalonia as a "nation," establishing an autonomous treasury, granting preferential status to the Catalan language, and expanding judicial autonomy.[246] On the day of the ruling, President José Montilla expressed widespread sentiment, stating:[247]

To comply does not mean to renounce. We will not relinquish anything agreed upon, signed, and voted for. We have felt mistreated in this process, but we are by no means defeated. On the contrary. No court can judge our feelings or our will. We are a nation. We will not abandon our pursuit of the full aspirations for self-government contained in the Statute we voted for.

The ruling triggered a dramatic surge in Catalan independentism.[248][249] In 1998, only 17% of Catalans favored independence, compared to 52% supporting autonomy and 15% favoring a federal solution. Support was higher among younger voters (24% for those aged 18–24) and Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) voters (60%), with 27% among Convergència i Unió (CiU) supporters, 13% for Iniciativa per Catalunya Verds (ICV), and 8% for Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC).[250]

The ruling marked the failure of the Statute's attempt to secure a distinct solution for Catalonia, undermining both CiU's "pactist" approach and PSC's federalist vision. Political initiative shifted from the government and parliament to pro-independence civil organizations.[251]

On July 10, 2010, a massive demonstration in Barcelona, under the slogan Som una nació, nosaltres decidim ("We are a nation, we decide"), rejected the ruling. Attended by all major Catalan parties except the People's Party (PP) and Citizens, it became a de facto plebiscite for independence. President Montilla, a socialist, was forced to leave under heavy security due to pressure from radical independentist groups.[248][249][252]

Four months later, the Catalan parliamentary elections saw CiU, led by Artur Mas, win without an absolute majority. Mas was elected President of the Generalitat by a simple majority in the second round of voting.[253][254] CiU's platform emphasized the "right to decide" rather than explicit independence, as Mas declared in his inauguration speech on December 27, 2010:[255]

I do not feel like a resistor, nor a liberator. I feel like a builder of Catalonia, of my country, a builder of the Catalan nation.

The elections saw heavy losses for the tripartite coalition (PSC lost 9 seats, ERC and ICV 10 each), leading to internal crises. PSC elected federalist Pere Navarro, while ERC chose independentist Oriol Junqueras, who sought closer ties with CiU to form a "sovereignist" majority. Solidaritat Catalana per la Independència, led by former FC Barcelona president Joan Laporta, won four seats. PP gained four seats, while Citizens retained three. Mas's government pursued a pacte fiscal to align Catalonia's financing with the Basque and Navarre economic agreement model, but rejections by both the socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and the PP government of Mariano Rajoy, formed after the 2011 Spanish general election, fueled further unrest.[256]

The rise of independentism was evident in the Catalunya, nou estat d'Europa demonstration on September 11, 2012, Catalonia's National Day, organized by the Catalan National Assembly. Two weeks later, the Parliament of Catalonia passed a resolution urging a "consultation" on Catalonia's collective future. Mas called early elections for November 25, 2012. Despite CiU losing 12 seats, ERC gained 11, ICV 3, and the Candidatura d'Unitat Popular (CUP) entered with three, forming a "sovereignist" majority. PSC continued its decline, losing 8 seats, while Citizens tripled its representation to nine, and PP gained one. This confirmed the "implosion of the party system" that began in 2006.[257]

On January 23, 2013, the Parliament approved the "Declaration of Sovereignty and Right to Decide of the People of Catalonia," with its first article declaring Catalonia a "sovereign political and legal subject," later annulled by the Constitutional Court in March 2014. On September 11, 2013, the Catalan Way human chain spanned Catalonia. On December 12, pro-consultation parties (CiU, ERC, ICV, CUP) agreed on referendum questions ("Do you want Catalonia to be a state?" and "If yes, do you want this state to be independent?") and set November 9, 2014, as the date.[258]

In January 2014, the Parliament's request for referendum powers was rejected by the Spanish Congress on April 8. Catalonia responded with its Catalan Law of Consultations to provide legal backing for the vote.[259] The September 11, 2014, demonstration formed a giant "V" in Barcelona, symbolizing support for the consultation.[260]

On July 25, 2014, former President Jordi Pujol admitted in a statement to holding undeclared funds abroad for 34 years, inherited from his father Florenci Pujol.[261] He expressed regret for not regularizing the funds, estimated at four million euros in Andorra, which reportedly benefited from Spain's 2012 tax amnesty.[262][263][264] The revelation sparked significant political controversy.[265]

Reign of Felipe VI (2014–present)

[edit]The November 9, 2014 Participatory Process and the Call for Plebiscitary Elections in September 2015

[edit]

On September 19, 2014, the day after the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, which garnered significant attention in Catalonia, the Parliament of Catalonia approved the Catalan Law of Consultations.[266] Published in the Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya on September 27, the law took effect, and President Artur Mas signed the decree for the November 9 consultation.[267] The Spanish government, led by Mariano Rajoy, promptly appealed to the Constitutional Court, which suspended the law and decree on September 29.[268]

On October 13, Mas acknowledged that the consultation could not proceed due to legal constraints.[269] The next day, he announced a non-binding "citizen participation process" under unsuspended parts of the consultation law.[270] On November 9, the participatory process took place with over 40,000 volunteers and no major incidents. Approximately 41% of the electorate (2,344,828 people) participated, with 80% (1,897,274 votes) favoring the "Yes-Yes" option for independence.[271]

On November 25, 2014, after the prosecutor's office filed a complaint against him, Mas outlined a plan to achieve independence within 18 months.[272] On January 14, 2015, he announced early regional elections for September 27, 2015, framing them as a plebiscite on independence.[273]

Despite the Constitutional Court's unanimous ruling on February 25, 2015, declaring the 9-N consultation unconstitutional,[274] Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC), ERC, Catalan National Assembly, Òmnium Cultural, and Association of Municipalities for Independence agreed on a unified roadmap for the sovereignist process, including a unilateral declaration of independence within 18 months if pro-independence parties won the elections. They stated that their programs would prioritize a vote for independence.[271] Rajoy warned that "no Spanish government will authorize the rupture of national sovereignty."[275]

From the 2015 Plebiscitary Elections to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence on October 27, 2017

[edit]

In the September 27, 2015, "plebiscitary" elections, Junts pel Sí (JxSí), a pro-independence coalition of CDC, ERC, and prominent sovereignist figures like Carme Forcadell and Muriel Casals, won 39.59% of the vote and 62 seats. Combined with CUP's 8.21% and 10 seats, pro-independence forces secured a parliamentary majority, though their combined vote share was 47.8%.[276]

On November 9, 2015, as Mas's investiture debate began, the Parliament approved a resolution with 72 independentist votes, proclaiming the start of a "democratic disconnection" from Spain, to last 18 months. The resolution, deemed legitimate by independentists due to their electoral "plebiscite" victory, urged the Generalitat to disobey Spanish institutions, including the "delegitimized" Constitutional Court, and comply only with Catalan parliamentary laws.[277] Rajoy's government appealed to the Constitutional Court, which suspended the resolution on November 11, warning of severe consequences, including criminal penalties, for non-compliance.[278]

Mas's investiture failed due to CUP's opposition, as JxSí's 62 seats required at least six CUP votes for a majority. In January 2016, with the deadline for new elections looming, Mas stepped aside, proposing Carles Puigdemont, who secured CUP's support and became President. In his investiture speech, ending with "Visca Catalunya Lliure" ("Long live free Catalonia"), Puigdemont pledged to achieve independence within 18 months, establishing "state structures" like a treasury, social security, and central bank, describing himself as the "president of post-autonomy and pre-independence."[279] Later, he shifted to proposing a binding independence referendum on October 1, 2017.[280]

On September 6, 2017, the Parliament passed the Referendum Law without a Consell de Garanties Estatutàries report and despite warnings from parliamentary lawyers of its unconstitutionality. Approved in a single vote without time for opposition analysis or amendments, Citizens, PSC, and PP deputies left the chamber, while Catalunya Sí que es Pot abstained.[281] The Law of Transition was similarly passed two days later.[282]

The Constitutional Court suspended both laws,[283] but Puigdemont's government proceeded with the referendum.[284] Rajoy vowed to prevent the vote, with the Prosecutor's Office filing complaints against Puigdemont, his government, and Parliament President Carme Forcadell.[285]

During the Operation Anubis on September 20, the Civil Guard raided the Treasury Department, leading to a crowd damaging patrol cars and delaying officials' exit. Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart, leaders of Catalan National Assembly and Òmnium Cultural, were later charged with sedition.[286][287]

Despite government efforts, the referendum occurred on October 1 without guarantees. Police interventions caused clashes, with images of charges gaining global attention.[288] The Generalitat reported a 43% turnout (2,286,217 voters), with 90% (2,044,038) voting "Yes," though results were unverified.[289]

On October 3, King Felipe VI addressed the nation, condemning the Generalitat's "unacceptable disloyalty" to the state.[290] Independentists criticized his lack of mediation. On October 10, Puigdemont declared a mandate for independence but suspended its effects for dialogue.[291] Rajoy initiated Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution proceedings.[292]

On October 27, the Parliament approved a unilateral declaration of independence in a secret vote, with constitutionalist parties (Citizens, PSC, PP) absent and most Catalunya Sí que es Pot deputies voting against.[293] Simultaneously, the Senate authorized Article 155, dismissing Puigdemont’s government and calling elections for December 21.[294]

From Catalonia’s Autonomy Intervention to the Fragmentation of Independentism (2017–2022)

[edit]

On October 27, 2017, the Spanish government dismissed Puigdemont and his cabinet, with Rajoy assuming the role of president and scheduling elections.[295] The Prosecutor filed charges against Puigdemont and others for rebellion, sedition, and embezzlement.[296] Puigdemont and four ministers fled to Brussels, while Oriol Junqueras and others were imprisoned.[297]

In the 2017 Catalan regional election, Ciudadanos led with 36 seats, but independentists (Junts per Catalunya, ERC, CUP) secured 70 seats, though with 47.49% of the vote.[298] On January 17, 2018, Roger Torrent, from ERC, became Parliament president.[299] He proposed Puigdemont for president, but the Constitutional Court required his physical presence, leading to delays.[300]

Attempts to invest Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Turull failed due to legal restrictions and CUP opposition.[301] On May 14, 2018, Quim Torra, Puigdemont’s choice, was elected, ending Article 155.[302]

The Trial of Catalonia independence leaders leaders from February to June 2019 resulted in 9–13-year sentences for sedition, with pardons granted in June 2021.[303][304]

In the 2021 Catalan regional election, independentists (ERC, Junts, CUP) strengthened their majority with over 50% of votes. Pere Aragonès was elected president on May 21, 2021, aiming to "complete independence."[305] The ERC-JunU coalition collapsed in October 2022 when Junts withdrew, with Jordi Sànchez declaring the "procés" definitively closed.[306]

References

[edit]- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 252.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 127; 220.

- ^ a b Smith 2014, p. 127.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 317-318.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 320-322.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 36.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 325It was then... that a significant number of Catalans evidenced a Spanish sentiment for the first time.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 29.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 23. Attachment to Catalan, reflecting an assumed consciousness of a distinct community, forced Charles IV's government during the War against the Convention to publish pamphlets inciting resistance in Catalan and recalling the country's past glories. French propagandists did the same.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 322.

- ^ Anguera 2001, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 318.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 57.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Anguera 2001, pp. 335.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 333.

- ^ Anguera 2001, p. 337.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 62.

- ^ a b c De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Claret & Santirso, p. 51-52.

- ^ Ferrer 2000, p. 118"In 1866, political Catalanism articulated for the first time, through parliamentary means, a demand for the restoration of the ancient political organization that had been taken away."

- ^ a b Ferrer 2000, pp. 118–120.

- ^ a b Smith 2014, p. 72.

- ^ a b Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 58–59.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 75.

- ^ a b Smith 2014, p. 73.

- ^ a b c De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Anguera 2001, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 74.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 90.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 65–66.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 81.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 115.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 93.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 60.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 74.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 75.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 166.

- ^ a b Smith 2014, p. 160.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 62.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 160.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 255.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 161.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 139.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 164–165.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Smith 2014, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 255–256.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 165.

- ^ a b Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Smith 2014, pp. 167–168.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 67–70.

- ^ Smith 2014, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 103.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 70.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 170.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 70–71.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 65–66.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 95.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 193.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 60.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 266.

- ^ Smith 2014, pp. 212–213.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 203.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 108.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 210.

- ^ a b Elliott 2018, p. 268.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 66.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 71.

- ^ a b c De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 74.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 72.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, p. 48.

- ^ a b Juliá 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 113.

- ^ Moreno Luzón 2009, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 114.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 114–115.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Juliá 1999, p. 31.

- ^ a b Canal 2018, p. 75.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, p. 52.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Tusell 1997, p. 280.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 191.

- ^ Tusell 1997, p. 279.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 75.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Canal 2018, pp. 79–80"This experience became a reference point for future self-governance efforts in nationalist rhetoric."

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 273.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 76–77.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 197.

- ^ Moreno Luzón 2009, pp. 448–453.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, pp. 89–91.

- ^ a b Juliá 1999, pp. 59–60.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, p. 114.

- ^ Moreno Luzón 2009, p. 471.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 276–277.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, p. 113.

- ^ a b Moreno Luzón 2009, p. 472.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, p. 115.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 58.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, pp. 116–121.

- ^ Barrio Alonso 2004, pp. 45–46.

- ^ De Riquer 2013, p. 123"It publicly declared Catalans’ priority for autonomy and indifference to Spain’s political regime."

- ^ De Riquer 2013, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Balcells 2010, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Balcells 2010, pp. 125–131.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 252, Macià’s time was yet to come.

- ^ a b c De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 279.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 130.

- ^ a b Roig i Rosich 1984, p. 70.

- ^ Ben-Ami 2012, p. 182.

- ^ a b González Calleja 2005, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Roig i Rosich 1984, p. 71.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Roig i Rosich 1984, pp. 70–71.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, p. 102.

- ^ García Queipo de Llano 1997, p. 108.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 79.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 279, Self-governance had no place in Primo’s unified Spain.

- ^ Puy 1984, p. 48.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, pp. 104–107.

- ^ García Queipo de Llano 1997, p. 106.

- ^ García Queipo de Llano 1997, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Pérez-Bastardas 1984, p. 56.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, p. 109.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, pp. 109–110.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Ben-Ami 2012, p. 186.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Roig i Rosich 1984, p. 74.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, p. 351.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, pp. 353–354.

- ^ a b c González Calleja 2005.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, p. 357.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 289–290.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Elliott 2018, p. 314.

- ^ Juliá 2009, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Juliá 2009, p. 32"Three declarations reflected the varied tendencies within the Catalan left coalition and significant improvisation."

- ^ a b c d De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 125.

- ^ Juliá 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Juliá 2009, pp. 33–34.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 126.

- ^ Jackson 1976, p. 81.

- ^ Gil Pecharromán 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Tusell 1997c, p. 72.

- ^ a b Tusell 1997c, p. 74.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Jackson 1976, p. 83.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 127.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 314, The statute satisfied moderate Catalan autonomy while keeping Catalonia in the Republic.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 128–133.

- ^ Gil Pecharromán 1997, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Canal 2018, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c Jackson 1976, p. 132.

- ^ a b c De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 133.

- ^ a b Elliott 2018, p. 293.

- ^ Termes 1999, p. 377.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 134.

- ^ a b Gil Pecharromán 1997, p. 92.

- ^ a b Casanova 2007, p. 129.

- ^ Gil Pecharromán 1997, p. 94.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 94.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 293–294.

- ^ a b Elliott 2018, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Gil Pecharromán 1997, p. 120.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 101.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 136.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 295.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 137.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Casanova 2007, pp. 318–321.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Bahamonde & Cervera Gil 1999, pp. 11–12.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Elliott 2018, p. 297.

- ^ a b De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 170.

- ^ Casanova 2007, pp. 403–405.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 153.

- ^ a b Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 157.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 160–161.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 170–171.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 171–172.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 165–166.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 174.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 175.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 175.

- ^ Juliana 2014, p. 73.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 178.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 179–180.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 302.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 213.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 192.

- ^ Tusell 1997b, p. 66.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 310–312.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, pp. 215–220.

- ^ Canal 2018, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 312–320.

- ^ Rodríguez Mesa 2017, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 217–221.

- ^ Bel 2013.

- ^ Sánchez-Cuenca 2012, pp. 72, 97.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 327, It declared that the reference to Catalonia as a 'nation' in the preamble had no legal effect... and ruled unconstitutional the addition of the words 'and preferential' regarding Catalan as 'the proper language'... The long-delayed ruling infuriated the Generalitat and nationalist organizations, who saw it as the culmination of a relentless anti-Catalan campaign.

- ^ Rodríguez Mesa 2017, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Sánchez-Cuenca 2012, p. 97.

- ^ a b García de Cortázar & González Vesga 2012, pp. 699–700.

- ^ De la Granja, Beramendi & Anguera 2001, p. 221.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 327.

- ^ Canal 2018, p. 152.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 328.

- ^ Rodríguez Mesa 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 223–226.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, pp. 226–228.

- ^ Claret & Santirso 2014, p. 228.

- ^ Vera Gutiérrez, Caro (July 19, 2014). "Paso a paso hacia la consulta" [Step by step toward the consultation]. El País (in Spanish). Retrieved June 6, 2025.

- ^ Rodríguez Mesa 2017, p. 42.

- ^ "Comunicado del señor Jordi Pujol y Soley" [Statement by Mr. Jordi Pujol y Soley]. El Mundo (in Spanish). July 25, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2025.