Coins of Augustus

Coins of Augustus were coins of the Roman Empire minted during the reign of Augustus. According to the catalogue The Roman Imperial Coinage, from the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, when power was fully consolidated under Augustus, until his death in 14 AD, 550 distinct coin types of various denominations were issued.

During Augustus reign, a series of measures known as the monetary reform were implemented. The Roman Empire established a system where the gold aureus and silver denarius formed the basis of a bimetallic monetary system. The intrinsic value of silver and gold coins matched their nominal value. Coins made of base metals were fiat, meaning their value was determined not by the metal content but by state legislation. A distinctive feature of the monetary system was the coexistence of both imperial and provincial coins. The issuance of imperial coins was directly controlled by the state or individuals authorized by the emperor, while provincial coins were issued by local authorities under the supervision of Roman governors.

While weight standards were consistent, the designs of the coins were not standardized. This led to the creation of hundreds of coin types across different denominations, with varying imagery. These coins often served as a tool for propaganda. Their active circulation, passing through many hands, combined with their value and relative durability, made them an effective medium for disseminating the ruler's views, ideas, and grandeur.

This article does not include information on coins featuring Augustus that were minted during the reigns of Julius Caesar or his successors.

Organization of coinage

[edit]Control over coin issuance

[edit]Since the time of the Roman Republic, the Senate oversaw coin minting. The process was managed by a board of three moneyers, typically young aristocrats, known as triumviri auro, argento, aere flando feriundo ("three men for casting and striking gold, silver, copper, and bronze").[1][2] In common parlance, they were called tres viri monetales,[3] loosely translated from Latin as "three monetary men". In 44 BC, under Julius Caesar, their number was increased to four. Augustus reduced it back to three.[3] In some cases, the Senate could delegate minting control to other magistrates, such as curule and plebeian aediles or quaestors.[2]

During military campaigns, commanders could oversee coin minting.[3] This practice was justified and served state interests. Commanders often seized enemy treasures, and supplying legions during wartime required funds. The title of "emperor" at this time was an honorary military distinction, awarded for exceptional military achievements. These issues are referred to as "imperial coins" or "military issues".[4][2] During the civil wars of the late 1st century BC, these became predominant.[2] The traditional organization of coinage was altered due to commanders' desire to control money issuance. Caesar replaced aristocratic moneyers with his freedmen.[2][5]

After Caesar's death, imperial and senatorial coinages coexisted.[6][7] Following the defeat of Mark Antony in 31 BC at the Battle of Actium and the consolidation of power under one ruler, both types of coins became "imperial". After Augustus came to power, he implemented measures that effectively centralized control over the issuance of silver and gold coins.[6][7] This was done gradually and in compliance with legal formalities. During the civil wars, Augustus' coins were among many issued by various military and political figures. After the civil wars ended in 27 BC, Augustus transferred minting rights to the Senate.[8] In 25 BC, through his legate Titus Publius Carisius, who was waging war against the Cantabri and Astures tribes in northern Spain, Augustus gained control over silver coin issuance in the western empire. A mint was established in the Colony of Emerita, located at modern-day Mérida. This mint produced silver denarii and quinarii, as well as copper asses and dupondii, featuring Augustus' image and Carisius' name.[8][9][10]

Under Augustus, the empire's provinces were divided into senatorial provinces and imperial provinces. The Senate appointed governors for the former, while the emperor appointed those for the latter. Using his imperium authority, Augustus established mints in provinces controlled by his legates, producing gold and silver coins. To avoid undermining the Senate's authority, Augustus refrained from issuing "imperial" coins in Rome.[6]

The largest imperial mint was established in Lugdunum (modern Lyon) in 15 BC during Augustus' visit to Gaul. The location was chosen strategically, as the region was rich in precious metals. In this imperial province, Augustus could issue coins without Senate approval. In 12 BC, the Rome mint was briefly closed, and Lugdunum became the primary mint for gold and silver coins.[11][12] In 9 BC, the Rome mint reopened, but only for issuing base metal coins, a decision driven by economic efficiency and the need to reduce abuses, as transporting small denomination coins from distant Lugdunum was challenging.[11][12][13]

In 4 BC, the name of the moneyer appeared for the last time on a copper quadrans.[14] This eliminated a republican element in coin design.[15] Copper coins retained the abbreviation "SC" (Senatus Consulto), indicating issuance with Senate approval. However, as historian M. G. Abramzon notes, this was "little more than a façade to mask the autocracy of Augustus and subsequent emperors".[8]

Mint operations

[edit]Information about the structure and operation of Roman mints is derived from inscriptions from the reign of Trajan (98–117 AD). The minister of finance (rationalis) was responsible for imperial mints, with mint overseers reporting to him. Technical operations were managed by a subordinate official, titled exactor auri, argenti et aeris manceps officinarum aerarium quinquae, item fraturariae argentariae. The mint staff included engravers (signatores), smelters (flaturarii), blank placers (suppostores), hammerers (malleatores), adjusters (aequatores), assayers (nummularii), and cashiers (dispensatores). Some production stages could be outsourced. The entire structure was ultimately accountable to the emperor, who could order specific designs, approve, or reject trial samples for mass production.[16][6][17]

For senatorial mints, a board of Senate-approved moneyers was responsible for issuance.[18] The technical aspects of production were likely similar to those of imperial mints.[19]

Differences in issuance and appearance compared to republican coins

[edit]Following the conquests of Caesar and Augustus, the Roman Empire became a vast state by ancient standards. To sustain monetary circulation, mass coin production was necessary, requiring improvements in minting processes.[20] Notably, iron dies were replaced with hardened iron dies, increasing the production of uniform denarii and aurei.[21] Coins from Augustus' era were flat and uniformly shaped, often featuring a dotted or (less commonly) continuous rim encircling the central design.[20]

Coins of Augustus during the civil wars

[edit]

Since BC, following the assassination of his adoptive father Julius Caesar, Augustus emerged as an independent political figure. In 43 BC, as part of the Second Triumvirate with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, he received Senate authorization to mint coins independently.[22] During this period of civil war, various military and political figures minted coins, often using mobile mints without Senate approval.[23][24] Augustus' pre-imperial coin issues were irregular. Historian M. G. Abramzon identifies four series of Augustus' coins from this period:[22]

- Under Senate control in Rome, 39–36 BC

- Military issues in Gaul, 42–32 BC

- Provincial issues in Gaul, 40–28 BC

- Military issues in Africa, 31–29 BC

The compilers of Roman Imperial Coinage classify the African issues as imperial coins.[25]

In 42 BC, Julius Caesar was deified, making Augustus the "divi filius" ("son of the divine"). Most of Augustus' pre-imperial coins reference his connection to his "divine" father. Aurei and denarii bore variations of his title "IMP CAESAR DIVI FILIO," meaning "Emperor Caesar, son of the divine".[23][24] Coins featuring both Julius Caesar and Augustus, either together or on opposite sides, were also issued.[22]

Among the Gallic imperial coins, one legionary coin dedicated to the XVI Gallic Legion is known. The obverse features a bearded Augustus, while the reverse shows the legion's lion symbol and the inscription "LEG. XVI." Some researchers believe it was minted in Gaul, others in Africa.[26]

Roman monetary units during Augustus' reign

[edit]After Augustus consolidated supreme power in the Roman Empire, a coherent monetary system was established with fixed ratios and weight standards for imperial coins. From one Roman pound (327.45 g) of gold, 42 aurei were minted, each valued at 25 silver denarii. Denarii were minted at 84 per pound.[27] Half-denominations, gold and silver quinarii, were issued sporadically. Coins were made from highly purified precious metals. Base metal coins, such as the sestertius and dupondius, were made of brass (orichalcum, or "yellow copper"), while the as, semis, and quadrans were made of pure copper. Augustus largely retained republican monetary units and their relative values. Under his rule, the aureus became a universal imperial coin, its value fixed by the state rather than the market price of gold.[27]

The metal content ratios for equivalent-value coins were as follows:[28]

- Gold to silver: 1 to 12.5 (one gold aureus weighed 12.5 times less than 25 silver denarii of equal value);

- Silver to brass: 1 to 28;

- Brass to copper: 28 to 45.

The monetary system established under Augustus was essentially bimetallic. The intrinsic value of silver and gold coins matched their nominal value. Base metal coins remained fiat, with their value determined by state laws.[29][30] After Augustus' monetary reform, the sestertius became the unit of account, used for expressing large sums.[31] In the Res Gestae Divi Augusti[32] and Suetonius' biography of Augustus, all expenditures, payments, and rewards are expressed in sestertii.[33][34]

The following table outlines the relationships between the main monetary units after Augustus' reform:[35]

| Nominal value in | Nominal value in | Nominal value in | Coin | Metal | Weight, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 100 | 400 | Aureus | Gold | ~7.85 |

| 12½ | 50 | 200 | Gold quinarius | Gold | ~3.92 |

| 1 | 4 | 16 | Denarius | Silver | ~3.79 |

| ½ | 2 | 8 | Silver quinarius | Silver | ~1.79 |

| ¼ | 1 | 4 | Sestertius | Brass | ~25 |

| 1⁄8 | ½ | 2 | Dupondius | Brass | ~12.5 |

| 1⁄16 | ¼ | 1 | As | Copper | ~11 |

| 1⁄32 | 1⁄8 | ½ | Semis | Copper | ~4.6 |

| 1⁄64 | 1⁄16 | ¼ | Quadrans | Copper |

Imperial mints

[edit]After defeating Mark Antony's forces and conquering Egypt, Augustus became the sole ruler of a vast empire. From 30 BC until his death, Roman imperial coins were minted at mints in around twenty cities. The locations of some mints remain unidentified (see Table 2).

| Location | Years | Denominations | Number of coin types | Catalogue numbers in The Roman Imperial Coinage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital of Lusitania Emerita Augusta (modern Mérida) | 25–23 (or 24–22[12]) BC[37] | Quinarii | 1 | 1 |

| Denarii | 9 | 2—10 | ||

| Dupondii | 1 | 11 | ||

| Asses | 14 | 12—25 | ||

| Colonia Caesaraugusta (modern Zaragoza) | 19–18 BC[38] | Aurei | 7 | 26—32 |

| Denarii | 17 | 33—49 | ||

| Colonia Patricia (modern Córdoba) | 20–19 BC[39] | Aurei | 4 | 50, 52, 53, 55 |

| Denarii | 5 | 51, 54, 56—58 | ||

| 19 BC[40] | Aurei | 15 | 59—63, 66, 68, 73, 76, 78, 80, 85, 88, 90, 91 | |

| Denarii | 22 | 64, 65, 67, 69—72, 74, 75, 77, 79, 81—84, 86, 87, 89, 92—95 | ||

| 18 BC[41] | Aurei | 8 | 104, 107, 109, 111, 112, 114, 116, 118 | |

| Denarii | 17 | 96—103, 105, 106, 108, 110, 113, 115, 117, 119, 120 | ||

| 18–17/16 BC[42] | Aurei | 10 | 125, 127, 129, 131, 133, 135, 138, 140, 141, 143 | |

| Gold quinarii | 3 | 121—123 | ||

| Denarii | 17 | 124, 126, 128, 130, 132, 134, 136, 137, 139, 142, 144—146, 148, 150, 152, 153 | ||

| Nîmes | 20–10 BC[43] | Dupondii | 1 | 154 |

| Asses | 3 | 155—157 | ||

| 10 BC–10 AD[43] | Asses | 1 | 158 | |

| 10–14 AD[44] | Asses | 3 | 159—161 | |

| Lugdunum (modern Lyon) | 15–13 BC[45] | Aurei | 6 | 163, 164, 166, 168, 170, 172 |

| Denarii | 6 | 162, 165, 167, 169, 171, 173 | ||

| 12 BC[46] | Denarii | 2 | 174, 175 | |

| 11–10 BC[47] | Aurei | 10 | 176, 177, 179, 181, 186, 188, 190, 192, 194, 196 | |

| Gold quinarii | 2 | 184, 185 | ||

| Denarii | 10 | 178, 180, 182, 183, 187, 189, 191, 193, 195, 197 | ||

| 8–7 BC[48] | Aurei | 2 | 198, 200 | |

| Gold quinarii | 1 | 202 | ||

| Denarii | 2 | 199, 201 | ||

| 7–6 BC[48] | Four aurei | 2 | 204, 205 | |

| Aurei | 2 | 206, 209 | ||

| Gold quinarii | 3 | 213—215 | ||

| Denarii | 5 | 207, 208, 210—212 | ||

| 6–9 AD[49] | Gold quinarii | 3 | 216—218 | |

| 13–14 AD[49] | Aurei | 4 | 219, 221, 223, 225 | |

| Denarii | 4 | 220, 222, 224, 226 | ||

| 15–10 BC[50] | Sestertii | 1 | 229 | |

| Asses | 1 | 230 | ||

| Quadrantes | 2 | 227, 228 | ||

| 10–14 AD[51] | Sestertii | 5 | 231, 240, 241, 247, 248 | |

| Dupondii | 4 | 232, 235, 236, 244 | ||

| Asses | 5 | 233, 237, 238, 242, 245 | ||

| Semisses | 4 | 234, 239, 243, 246 | ||

| Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier) | Second half of Augustus' reign[52] | Quadrantes | 1 | 249 |

| Rome and Brindisi (uncertain which coins were minted in Rome or Brindisi) | 32–29 BC[53] | Aurei | 5 | 258—262 |

| Denarii | 9 | 250—257, 263 | ||

| 32–29 BC[54] | Aurei | 3 | 268, 273, 277 | |

| Quinarii | 1 | 276 | ||

| Denarii | 9 | 264—267, 269—272, 274, 275 | ||

| Rome | 19–12 BC[55] | Aurei | 20 | 278, 279, 285, 286, 293, 298, 302, 308, 312, 316, 321, 337, 339, 350, 369, 402, 409, 411, 413, 419 |

| Denarii | 74 | 280—284, 287—292, 294—297, 299—301, 303—307, 309—311, 313—315, 317—320, 322, 338, 340, 343, 344, 351—368, 397—401, 403—408, 410, 412, 414—418 | ||

| Sestertii | 15 | 323, 325, 327—330, 341, 345, 348, 370, 374, 377, 380, 383, 387 | ||

| Dupondii | 19 | 324, 326, 331—336, 342, 346, 347, 349, 371, 372, 375, 378, 381, 384, 388 | ||

| Asses | 14 | 373, 376, 379, 382, 385, 386, 389—396 | ||

| 9–4 BC[13] | Dupondii | 5 | 426, 429, 430, 433, 434 | |

| Asses | 12 | 427, 428, 431, 432, 435—442 | ||

| Quadrantes | 32 | 420—425, 443—468 | ||

| 10–12 AD[14] | Asses | 3 | 469—471 | |

| Unidentified mint in northern Peloponnese | 21 BC[56] | Quinarii | 1 | 474 |

| Denarii | 2 | 472, 473 | ||

| Samos | 21–20 BC[56] | Denarii | 1 | 475 |

| Ephesus | 28–20 BC[57] | Cistophori | 7 | 476—482 |

| Sestertii | 2 | 483—484 | ||

| Asses | 2 | 485—486 | ||

| Pergamon | 27–26 BC[58] | Cistophori | 7 | 487—494 |

| 28–15 BC[59] | Sestertii | 2 | 496, 501 | |

| Dupondii | 3 | 497, 499, 502 | ||

| Asses | 4 | 495, 500, 503, 504 | ||

| Semisses | 1 | 498 | ||

| 19–18 BC[60] | Cistophori | 6 | 505—510 | |

| Aurei | 6 | 511—514, 521, 522 | ||

| Denarii | 10 | 515—520, 523—526 | ||

| Antioch | After 23 BC[61] | Asses | 1 | 528 |

| Semisses | 1 | 529, 530 | ||

| Unidentified city in Cyrenaica | 31–29 BC[25] | Aurei | 1 | 533 |

| Denarii | 3 | 531, 534, 535 | ||

| Quinarii | 1 | 532 | ||

| Mints with unidentified locations | Cistophori | 1 | 527 | |

| Four aurei | 1 | 546 | ||

| Aurei | 5 | 536—539, 544 | ||

| Denarii | 7 | 540—543, 545, 547, 548 | ||

| Sestertii | 1 | 549 | ||

| Dupondii | 1 | 550 |

Coins of Augustus as a tool of political propaganda

[edit]

In the absence of mass media, coins served as a tool for political propaganda. Their widespread circulation, value, and durability made them effective for spreading the ruler's views, ideas, and grandeur.[63][64]

Many coin types targeted the backbone of Roman power—legionaries and veterans. These featured allegorical military themes[65] and celebrated achievements enabled by the army.[66] The emperor was not only a statesman but also the army's supreme commander. To emphasize unity with the military, Augustus was depicted on horseback or in military attire.[67]

Coins minted in Nîmes, in particular, highlighted veterans' past achievements. The obverse featured portraits of Augustus and Agrippa, with the inscription "IMP DIVI F." The reverse depicted a crocodile chained to a palm tree, topped with a wreath and palm shoots below. The inscription "COL NEM" stood for "Colonia Nemausus." This design commemorated the veterans of the Egyptian campaign, many of whom received land grants in Narbonensian Gaul. The palm and crocodile imagery recalled their past exploits.[68][69]

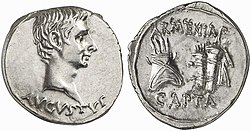

"Provincia capta" type

[edit]

A distinct group of coins was minted to commemorate the conquest of provinces, bearing the province's name and inscriptions such as "CAPTA," "DEVICTA," "RECEPTA," "SUBACTA," or "PACATA." These coins highlighted Rome's military successes, though they did not always reflect reality. After Mark Antony's allies lost power in Asia Minor, and the province aligned with Augustus, special quinarii were issued. Their reverse featured Victoria standing on a cista mystica, flanked by two snakes, with the inscription "ASIA RECEPTA," signifying Augustus' control over Asia, depicted on the obverse. These coins were likely minted as Augustus and his forces moved through Asia and Syria toward Egypt, where Mark Antony and Cleopatra had fled.[70]

In 30 BC, after the deaths of Cleopatra and Caesarion, Egypt became a Roman province under an imperial prefect appointed by Augustus.[71] This milestone was reflected on denarii from 29–27 BC, inscribed "AEGVPTO CAPTA" ("Egypt Conquered").[72][73]

Subsequent coins in this series were minted after Tiberius' campaign in Armenia in 20 BC, which restored the pro-Roman Tigranes III to the throne. Though Roman successes against the Parthian Empire for control of Armenia were temporary, they were commemorated on coins with legends such as "ARMENIA CAPTA",[74] "ARMENIA RECEPTA", and others incorporating these phrases. Propaganda also emphasized victories over the Parthians with inscriptions like "PARTHICIS RECEPTIS" and its abbreviations,[75] as well as depictions of a kneeling Parthian (or Armenian) warrior.[76]

Triumphal issues celebrating Roman victories

[edit]

Nearly all major military successes were depicted on coins. The victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium was commemorated on several coins: Augustus with a parazonium and spear standing on a rostral column; naval and military trophies on a ship's prow; and Victoria on a ship's prow with a wreath and palm branch, with Augustus in a triumphal chariot on the reverse.[77] A notable denarius features the Arch of Augustus, built to commemorate the Actium victory, providing insight into its design.[78]

Commemorative coins also include those depicting trophies from the Cantabrian Wars, such as helmets, cuirasses, spears, shields, and piles of weapons.[79]

"Princeps iuventutis" type and depictions of heirs

[edit]

From Augustus' reign, the practice of depicting heirs on coins began, introducing the public to potential future rulers. Until his death in 12 BC, Augustus' friend and ally Agrippa was his heir. Several coins, aside from those minted in Nîmes, feature Agrippa. The title "Princeps iuventutis" ("Leader of the Youth") was awarded to the junior member of the imperial family, presumed heir. After Agrippa's death, Augustus' grandsons and adopted sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, became heirs. Their attributes—a silver shield and spear—are depicted on coins. Some coin types show Gaius Caesar on horseback.[81]

The "Princeps iuventutis" title conferred no additional powers. At age 15, Gaius and Lucius were appointed consuls. Augustus involved them in state affairs from a young age. On denarii and aurei, they are depicted holding shields with two spears behind and a sacrificial vessel (simpulum) and lituus above. The legend "C • L • CAESARES • AVGVSTI • F • COS • DESIG • PRINC • IVVENT •" translates to "Gaius and Lucius Caesars, sons of Augustus, designated consuls, leaders of the youth." The cult objects indicate they performed augury.[82] Coins featuring Gaius and Lucius include rare four-aureus medallions, weighing over 30 g.[83] Imitations of these denarii were produced in Transcaucasia and the Rhine-Danube region, with Transcaucasian copies being crude and schematic.[84] Some suggest these were minted in large quantities for trade with Eastern countries, including India.[85]

After the deaths of Gaius and Lucius, Tiberius became Augustus' heir. Coins featuring his bust or him in a triumphal quadriga with a scepter were issued in the final years of Augustus' life.[49]

"Debellator" type

[edit]

Coins classified as "Debellator" ("Conqueror" or "Victor") depict Roman commanders as merciful and magnanimous victors. These coins show Augustus seated on a curule chair, receiving a child from a defeated barbarian.[86]

Religious motifs on Augustus' coins

[edit]Deification of Caesar

[edit]

Most of Augustus' coins from the civil war period and many from the principate bear the inscription "D(IVI) F(ILIO)." Some feature the image of the "Divine Julius", emphasizing the connection between the triumvir and young emperor with his "divine" father.[87]

Augustus and Numa Pompilius

[edit]Augustus placed significant emphasis on traditional religious cults. He was a member of several priestly colleges, serving as a quindecimvir sacris faciundis, epulone, Arval Brother, fetial, and Pontifex Maximus. Coins featuring Augustus on one side and the semi-legendary king Numa Pompilius on the other highlight parallels between the emperor and the deified king, portraying Augustus as a "new Numa".[88]

Deities on Augustus' coins

[edit]

Coins of Augustus feature gods of the Roman pantheon. Some are standard for Roman coins, others are Augustus' patrons, and some are linked to the emerging imperial cult.

The goddess of victory Victoria appeared on Roman coins as early as 269 BC, a staple on victoriati and quinarii. She is featured on many of Augustus' coins.[89][90]

The war god Mars and the personification of peace Pax frequently appear on Augustus' coins. Pax symbolizes the long-desired peace and stability achieved under Augustus.[91] Pax appears on cistophori minted after the Actium victory, with the obverse legend "IMP CAESAR DIVI F COS VI LIBERTATIS PR VINDEX" ("Defender of the Liberty of the Roman People"), emphasizing Augustus' divine lineage, peace establishment, and protection of Roman freedom.[92]

Venus, patroness of the Julian family, dominates pre-Actium coins but appears later as well.[93] In 19 BC, under the moneyer Quintus Rustius, denarii and aurei featured Fortuna Felix and Fortuna Victrix.[94][95]

Some coins depict deities with features of Augustus or his family, a practice rooted in Hellenistic traditions. In the eastern empire, Augustus' cult drew on ancient traditions. Coins portray Augustus with features of Apollo, or Apollo with Augustus' features.[96] Apollo was central to the Roman pantheon, and Augustus considered him his patron in the battles of Philippi and Actium. Coins featuring Apollo with the abbreviation "ACT" ("Actian") were issued multiple times.[96] Coins also depict Augustus' daughter Julia as Diana[97] and his wife Livia as Pax.[98]

Priestly implements on coins

[edit]

Augustus' religious activities, as an augur and Pontifex Maximus, were reflected on coins. These depict ritual plowing scenes by the emperor and priestly attributes like the augural staff lituus, simpulum, patera, and others.[99]

Cults of sacred standards and legionary eagles

[edit]Military standards, such as the legionary aquila, vexillum, labarum, and manipular signa, were sacred to Romans. Their loss was considered a disgrace. In 20 BC, Augustus' stepson Tiberius compelled the Parthian king Phraates IV to return standards and prisoners captured during the failed campaigns of Crassus in 53 BC, Lucius Decidius Saxa in 40 BC, and Mark Antony in 36 BC. This event was commemorated on coins with the legend "Signis receptis" or a Parthian handing over a standard.[100]

Capricorn and celestial bodies on Augustus' coins

[edit]

Suetonius recounts that during Augustus' stay in Apollonia, he and Agrippa visited the astrologer Theogenes' observatory. Initially reluctant to reveal his birth hour, fearing a less favorable prediction than Agrippa, Augustus eventually complied. Theogenes recognized his destiny, leading Augustus to publicize the celestial signs of his birth and issue a silver coin featuring Capricorn, his birth sign.[101] A discrepancy with Suetonius' statement that Augustus was born on September 23 under the consuls Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius[102] was noted by astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). Augustus' attachment to Capricorn may relate to his conception, calendar reforms, the Moon's position, or simply personal superstition.[103]

Capricorn was depicted alone or with a cornucopia and/or a globe, symbolizing eternity. One coin pairs Capricorn with Aurora. Stars, comet, and the Moon on coins, according to M. G. Abramzon, promote the "golden age" ushered in by Augustus and the eternal greatness of the emperor and Roman Empire.[104]

Architectural monuments on Augustus' coins

[edit]Coins featuring temples, basilicas, and other structures were part of imperial propaganda, reinforcing the "Roman myth." These numismatic depictions are valuable for historians and architects in reconstructing their appearance.[105]

Coins depict the temples of Mars the Avenger, Jupiter Tonans, Jupiter Olympius, Diana, and Roma and Augustus.[106]

The depiction of Mars the Avenger fulfills Augustus' vow during the Philippi campaign to avenge Caesar's assassins.[107] Coins dated 19–18 BC show Mars the Avenger in his temple, dedicated in 2 BC at the Forum of Augustus. British numismatist Harold Mattingly suggests these coins may depict another Mars temple on the Capitoline Hill.[107]

The temple of Jupiter Tonans on the Capitoline Hill was built by Augustus to commemorate his escape from a lightning strike that killed a torch-bearing slave. The coin depicts a six-columned temple with a three-step podium, housing a statue of Jupiter with a scepter and thunderbolt.[108]

The depiction of the Temple of Jupiter Olympius in Athens, begun in the 6th century BC and completed in the 2nd century AD, indicates significant progress under Augustus.[109]

The Temple of Roma and Augustus in Ephesus was a religious and political center in the province of Asia, later depicted on other emperors' coins.[110]

Altars, such as those dedicated to Roma and Augustus in Lugdunum, were also depicted, including altars to Fortuna Redux, Providentia, Diana, and Roma and Augustus. Cistophori from 28–27 BC show Diana's altar with two deer.[111]

Triumphal arches commemorating military victories were also featured on coins.[112] Some coins depict city walls or panoramic city views.[113]

Titulature on Augustus' coins

[edit]Following Caesar's deification, Augustus became the "son of the divine," reflected on coins. In 27 BC, the Senate bestowed honors on him, including the name "Augustus," making his full official name "Imperator Caesar Augustus, son of the divine" (Imperator Caesar Augustus divi filius), or simply Caesar Augustus.[114]

Coin inscriptions help date issues. In Roman Imperial Coinage, coins with "IMP X" (likely indicating Augustus' tenth year of imperium) are dated to 15–13 BC;[45] "IMP XI" to 12 BC;[46] "IMP XII" or "TR POT XIII" (tribunician power, 13th year) to 11–10 BC;[47] "TR POT XVI" to 8–7 BC, "IMP XIIII" to 8 BC;[48] "TR POT XVII" to 7–6 BC;[83] "TR POT XXIIII" to 1–2 AD;[83] "TR POT XXV" to 2–3 AD;[83] "TR POT XXVII" to 4–5 AD;[83] and "TR POT XXVIIII," "TR POT XXX," "TR POT XXXI" to 6–9 AD.[49]

On February 5, 2 BC, Augustus received the title "Father of the Fatherland" (pater patriae or parens patriae), also reflected on coins.[115]

Some coins note Augustus' religious roles as augur and Pontifex Maximus.[50] During a brief period of accord with Mark Antony, coins indicate Augustus' role as pontiff. African coins from 31–29 BC bear the legend "AVGVR PONTIF".[116]

Provincial coins

[edit]

In addition to imperial coins, the Roman Empire minted provincial coins. Unlike imperial coins, their issuance was not regulated by central authorities or emperor-authorized individuals.[117] Provincial coins were vital for local circulation, often replicating traditional local units like tetradrachms in the eastern Mediterranean, to provide small change.[118]

The term "provincial coins" is ambiguous. In 1930, Kurt Regling identified their primary characteristic as issuance under semi-autonomous entities rather than Roman authorities.[119] This raises questions, as determining Roman governors' influence over local issues is often challenging. Governors likely oversaw provincial mints to some extent.[120] Many provincial coins feature the emperor's portrait, unlike imperial coins minted in Rome. For non-specialists, distinguishing between provincial and imperial coins is easiest by referencing catalogues like The Roman Imperial Coinage or Roman Provincial Coinage. Some coins, such as cistophori and issues from Colonia Caesaraugusta, appear in both, indicating both imperial and provincial characteristics and a lack of clear classification criteria.[121]

Monetary circulation in the Roman Empire during Augustus' reign

[edit]While Augustus introduced no fundamentally new elements in coin issuance or circulation compared to the Roman Republic, he established a robust monetary system that maintained consistent ratios between denominations for about two centuries. The empire adopted a silver-gold bimetallism system alongside fiat base metal coins, whose value was state-determined.[122][123]

A key feature of monetary circulation under Augustus, the first Roman emperor, was the coexistence of imperial and provincial coins. Imperial coin issuance was controlled by the state or emperor-authorized individuals, while provincial coins were issued by local authorities under Roman governors' supervision.[119][120] Gold aurei were exclusively imperial, while small change was mostly provincial. The copper as, a fiat coin, circulated in Rome, Italy, Gaul, Asia, Syria, and Roman Egypt. In other regions, provincial coins served as small change.[124]

Silver coins were minted as both imperial and provincial. Monetary circulation differed between the empire's western and eastern regions. In conquered areas like Gaul, Spain, and Britain, monetary systems were underdeveloped, while Greece and Asia had centuries-old traditions. Eastern trade with the Parthian Empire brought goods from India. Thus, in the eastern empire, tetradrachms and cistophori (equivalent to three denarii) circulated alongside denarii and aurei, with cistophori having both imperial and provincial characteristics.[125]

References

[edit]- ^ Zvarich 1980.

- ^ a b c d e Abramzon 1995, p. 62, "Part One. Chapter II. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ a b c Zograf 1951, p. 35.

- ^ Sayles, W. G. (2007). Ancient Coin Collecting III: The Roman World - Politics wierd Propaganda [Ancient Coin Collecting III: The Roman World - Politics and Propaganda] (2nd ed.). Iola, WI: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-89689-478-5. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ Suetonius, Divine Julius 76 (3)

- ^ a b c d Zograf 1951, p. 36.

- ^ a b Abramzon 1995, p. 63, "Part One. Chapter II. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ a b c Abramzon 1995, p. 64, "Part One. Chapter II. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 5.

- ^ Mattingly 2005, p. 96.

- ^ a b Mattingly 2005, p. 95—96.

- ^ a b c Sydenham 1920, p. 18.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 74—78.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 78.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 67, "Part One. Chapter II. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 70—71, "Part One. Chapter II. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ Kazmanova 1969, p. 73—74, "VI. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ Kazmanova 1969, p. 82—83, "VI. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 71, "Part One. Chapter II. Organization of Coinage".

- ^ a b Kazmanova 1969, p. 57, "IV. Systematization of Ancient Coins".

- ^ Kazmanova 1969, p. 79, "V. Coinage Techniques".

- ^ a b c Abramzon 1995, p. 325, "Augustus' Religious Program in the Pre-Actium Period".

- ^ a b Crawford 1985, p. 256.

- ^ a b Harl 1996, p. 51.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 84.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 146, "Legionary Coins".

- ^ a b Mattingly 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Mattingly 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Mattingly 2005, p. 106—107.

- ^ Zograf 1951, p. 52.

- ^ Zvarich 1980, "Sestertius".

- ^ Octavian Augustus 1985.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 30, 40, 41, 46, 68, 71, 101

- ^ Res Gestae Divi Augusti 15, 16, 17, 21

- ^ Mattingly 2005, p. 107—108.

- ^ Depeyrot 2006, p. 33.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 41—42.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 43—45.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 45—46.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 46—48.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 48—49.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 49—51.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 51.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 52.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 52—53.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 53.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 53—54.

- ^ a b c C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 54—55.

- ^ a b c d C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 56.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 57.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 57—58.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 58.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 59—60.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 60—61.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 61—74.

- ^ a b C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 79.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 70.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 81.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 81—82.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 82—83.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 83—84.

- ^ Obverse and Reverse of History. Moscow: International Numismatic Club. 2016. p. 216. ISBN 978-5-9906902-6-4.

- ^ Cunz 1998, p. 347.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 94—95, "Coins as a Means of Propaganda for Military Policy".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 95—96, "Coins as a Means of Propaganda for Military Policy".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 97, "Coins as a Means of Propaganda for Military Policy".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 234, "Coins as a Means of Propaganda for Military Policy".

- ^ "Augustus & Agrippa Nemausus Crocodile" [Augustus & Agrippa Nemausus Crocodile]. www.moneta-coins.com. Moneta Gallery Coin Museum. Archived from the original on 2018-06-18. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 51—52.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 166, "Provincia capta Type and Other Similar Series".

- ^ Mazzarino, Santo (1976). L'impero romano [The Roman Empire]. Roma-Bari. pp. 66–67.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Denarius of Octavian, "AEGYPTO CAPTA"" [Denarius of Octavian, “Egypt Conquered”]. www.dartmouth.edu. Hood Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2018-06-25. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ "Research Coins: Affiliated Auction" [Research Coins: Affiliated Auction]. www.cngcoins.com. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. Archived from the original on 2018-06-17. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 167, "Provincia capta Type and Other Similar Series".

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 83.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 62.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 177, "Triumphal Issues Celebrating Roman Victories".

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 60.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 179, "Triumphal Issues Celebrating Roman Victories".

- ^ Obverse and Reverse of History. Moscow: International Numismatic Club. 2016. p. 94. ISBN 978-5-9906902-6-4.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 54.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 236, "Triumphal Issues Celebrating Roman Victories".

- ^ a b c d e C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 55.

- ^ Kazmanova 1969, p. 96, "Imitations of Augustus' Denarii with Gaius and Lucius Caesars on the Reverse".

- ^ Kazmanova 1969, p. 79, "Changes in Coin Production Techniques in the Imperial Era".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 239—240, "Debellator Type".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 325, "Octavian's Religious Program in the Pre-Actium Period".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 340, "Octavian's Religious Program in the Pre-Actium Period".

- ^ Zvarich 1980, "Victoriatus".

- ^ Shulavov, P. V. "Quinarius" [Quinarius]. Great Russian Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. p. 494. Archived from the original on 2023-01-03. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 345, "Augustus' Cult and Religious Themes on His Coins".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 334, "Augustus' Cult and Religious Themes on His Coins".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 330, "Augustus' Cult and Religious Themes on His Coins".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 344, "Augustus' Cult and Religious Themes on His Coins".

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 64—65.

- ^ a b Abramzon 1995, p. 336, "Augustus' Cult and Religious Themes on His Coins".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 347—348, "Emergence of the Julio-Claudian Dynastic Cult".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 351—352, "Emergence of the Julio-Claudian Dynastic Cult".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 265—267, "The Emperor and His Role in the Army's Religious Life. Coins with Priestly Implements".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 269—270, "Cults of Sacred Standards and Legionary Eagles".

- ^ Suetonius, Divine Augustus 94 (12)

- ^ Suetonius, Divine Augustus 5

- ^ Barton, T. (1995). "Augustus and Capricorn: Astrological Polyvalency and Imperial Rhetoric" [Augustus and Capricorn: Astrological Polyvalency and Imperial Rhetoric]. The Journal of Roman Studies. 85: 33–51. doi:10.2307/301056. JSTOR 301056.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 337—339, "Augustus' Religious Program and the Emergence of the Julio-Claudian Dynastic Cult on Coin Types".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 496—497, "Architectural Monuments on Coins".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 499—503, "Architectural Monuments on Coins".

- ^ a b Abramzon 1995, p. 499—500, "Temple of Mars the Avenger".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 499—500, "Temple of Jupiter Tonans".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 500—501, "Temple of Jupiter Olympius".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 503, "Temple of Roma and Augustus".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 516—517, "Altars".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 519—520, "Triumphal Arches".

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 529, "Architectural Complexes".

- ^ Goldsworthy, A. (2014). Augustus. First Emperor of Rome. New Haven; London: Yale University Press. p. 236.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 55—57.

- ^ Abramzon 1995, p. 266, "The Emperor and His Role in the Army's Religious Life. Coins with Priestly Implements".

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 19.

- ^ C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson 1984, p. 19—20.

- ^ a b Amandry 2012, p. 391—392.

- ^ a b Bunson, M. (2002). "Coinage". Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Revised Edition [Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Revised Edition]. New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 131–132. ISBN 0-8160-4562-3. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ Amandry 2012, p. 393.

- ^ Zvarich 1980, "Bimetallism".

- ^ Crawford 1978, p. 154—155.

- ^ Mattingly 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Mattingly 2005, p. 90.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abramzon, M. G. (1995). Coins as a Means of Propaganda for the Official Policy of the Roman Empire. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology. p. 656. ISBN 5-7114-0063-0.

- Abramzon, M. G. (1992). The Formation of the Imperial Cult in Ancient Rome (Based on Numismatic Evidence). Dissertation Abstract for the Degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences (100 ed.). Moscow: MPGU named after V. I. Lenin Printing House. p. 16.

- Obverse and Reverse of History. Moscow: International Numismatic Club. 2016. p. 216. ISBN 978-5-9906902-6-4.

- Octavian Augustus (1985). "Deeds of the Divine Augustus". In Nemirovsky A. I., Dashkova M. F. (ed.). "Roman History" by Velleius Paterculus. Voronezh: Voronezh University Publishing House. p. 211.

- Suetonius (1933a). "Divine Julius". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Moscow—Leningrad: Academia.

- Suetonius (1933b). "Divine Augustus". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Moscow—Leningrad: Academia.

- Zvarich, V. V. (1980). Numismatic Dictionary (4th ed.). Lviv: Vyshcha Shkola.

- Zograf, A. N. (1951). Ancient Coins (4000 ed.). Moscow, Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House. p. 265.

- Kazmanova, L. N. (1969). Introduction to Ancient Numismatics (6800 ed.). Moscow: Moscow University Publishing House. p. 303.

- Mattingly, Harold (2005). Coins of Rome from Ancient Times to the Fall of the Western Empire. Collector’s Books. ISBN 1-932525-37-8.

- Amandry, M. (2012). "Chapter 21. The Coinage of the Roman Provinces through Hadrian". In Metcalf, W. E. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

- Amandry, M.; Burnett, A.; Carradice, I.; Ripollès, P. P.; Butcher, M. S. (2014). Roman Provincial Coinage Supplement 3. New York: The American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-89722-333-1.

- Crawford, M. H. (1978). "Ancient Devaluations: A General Theory". Publications de l'École Française de Rome. 37 (1): 147–158. ISBN 2-7283-0449-1.

- Crawford, M. H. (1985). "Chapter 17. The Emperor Augustus". Coinage and Money under the Roman Republic. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 256–280. ISBN 0-520-05506-3.

- Cunz, Rainer (1998). Historical Commission for Lower Saxony and Bremen (ed.). "God's Friend, the Priests' Enemy. On the Propaganda Coins of "Mad Christian"". Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte (in German). 70. Hannover: Verlag Hahnsche Buchhandlung: 347–362. ISSN 0078-0561. Archived from the original on 2018-06-17.

- Depeyrot, Georges (2006). Roman Coinage: 211 BC – 476 AD. Editions Errance. p. 212. ISBN 2877723305.

- Harl, K. W. (1996). Roman Economy, from 300 BC to AD 700. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5291-9.

- Howgego, Christopher (1994). "Coin Circulation and the Integration of the Roman Economy". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 7: 5–21. doi:10.1017/S1047759400012472.

- C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson (1984). The Roman Imperial Coinage. Vol. I. London—Oxford: Spink & Son LTD. ISBN 0-907605-09-5.

- Sutherland, C. H. V. (1945). "The Gold and Silver Coinage of Spain under Augustus". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, Sixth Series. 5 (1/2): 58–78.

- Sydenham, E. A. (1920). "The Coinages of Augustus". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. 20: 17–56. JSTOR 42663784.