Chae Chan Ping v. United States

| Chae Chan Ping v. United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 28–29, 1889 Decided May 13, 1889 | |

| Full case name | Chae Chan Ping v. United States |

| Citations | 130 U.S. 581 (more) 9 S. Ct. 623; 32 L. Ed. 1068; 1889 U.S. LEXIS 1778 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Appeal from the circuit court of the United States for the Northern district of California |

| Holding | |

| |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

| Majority | Field, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Art. III and Scott Act of 1888 | |

Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889), or Chinese Exclusion Case, is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the constitutionality of the Scott Act of 1888, a follow-up to the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Chinese Exclusion Act barred the entry from abroad of Chinese people into the United States, the other barred reentry from abroad of Chinese people in the United States.[1]

The case arose concerning Chae Chan Ping, a Chinese laborer who moved to the United States in 1875, legally resided in San Francisco for over a decade, and whose return voyage from a trip to British Hong Kong was pending when the Scott Act became effective.[2] Ping's legal challenge to the reentry bar was aided by Chinese immigrant groups and advocated on his behalf by an elite "dream team" of lawyers.[3]

The case is viewed as "the grandfather of immigration law cases" and is significant both in the broad judicial deference conveyed and role of the case in forming the plenary power and consular nonreviewability doctrines in immigration and nationality law.[4][5]

Background

[edit]Burlingame Treaty

[edit]In 1868, the United States and China agreed to the Burlingame Treaty, which established formal friendly relations between the two countries and granted China most favored nation status. The treaty encouraged immigration from China and granted some privileges to citizens of either country residing in the other but withheld the privilege of naturalization for immigrants from China.[6] The treaty was later amended by the Angell Treaty of 1880 to suspend the entry of new Chinese immigrants.[7]

Chinese Exclusion Act and Scott Act

[edit]

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, forbidding the immigration of new laborers from China to the United States. The rights of prior immigrants were not significantly affected. An 1884 Amendment to the Chinese Exclusion Act required Chinese immigrants to obtain re-entry permits if they wished to return after leaving the United States. Subsequently, the Scott Act of 1888 was signed by President Grover Cleveland, which the barred such reentry and voided all prior reentry permits.[9][10]

Chae Chan Ping

[edit]Chae Chan Ping was a laborer from China who immigrated to San Francisco, California, in 1875. On June 2nd, 1887, he left San Francisco to travel to British Hong Kong, obtaining an appropriate reentry permit before departure. Unbeknownst to Ping, the Scott Act had became effective in the intervening time and barred his return.[2] Petition for writ of habeas corpus was filed on behalf of Ping on October 10, 1888, and swiftly heard thereafter on October 12th before Circuit Judges Lorenzo Sawyer and Ogden Hoffman Jr.. On October 15th, the Circuit Court ruled against Ping, setting the stage for the case to be heard before the Supreme Court.[3] Historically, direct review requesting writ of habeas corpus was the only means of challenging immigration-related legal orders.[11]

Supreme Court

[edit]Arguments

[edit]Chae Chan Ping was represented by prominent lawyers at the time, including George Hoadly, James C. Carter, and Thomas S. Riordan, all of whom had previously won cases before the federal judiciary which resulted in outcomes favorable to Chinese immigrants.[3] Despite his lower socioeconomic status as a day laborer, Ping's high-quality "dream team" legal counsel was made possible through Chinese-American benevolent societies which sought to use him as a test case to challenge Chinese exclusion.[2] Lawyers for Ping argued that the Scott Act violated the guarantees set forth in the Burlingame Treaty.[3] Further, they argued that the Act deprived Ping of "life, liberty, or property, without due process of law" in violation of the Fifth Amendment since it was argued that Ping's certificate permitting his reentry had vested him with a property right that could not be "taken away by mere legislation".[12]

Arguing on behalf of the United States was the Solicitor General George Jenks. The State of California submitted an amicus curiae brief in favor of the United States position. The amicus brief was written by John F. Swift, whom nine years earlier had negotiated the Angell Treaty of 1880.[3] The United States made its arguments in the context of the law of nations, positioning the case as part of a larger foreign affairs dispute with the Chinese government, and that with this in consideration, the government had complete power to bar the entry not only of Chae Chan Ping, but any other foreigner or class of foreigners, whatever their background might be, and that such expansive foreign affairs powers laid wholly within the purview of the federal government, not the states.[13]

Decision of the Court

[edit]

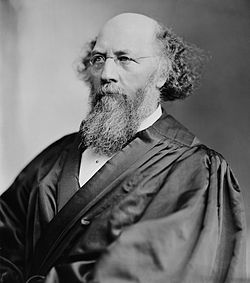

In a unanimous decision on May 13, 1889, authored by Justice Stephen Johnson Field, the Supreme Court held that the Scott Act of 1888 was constitutional; thus, Chae Chan Ping was excluded from reentry to the United States and expelled by removal to China.[2] Justice Field had previously ruled, as Chief Justice of California, against the discriminatory, anti-Chinese Pigtail Ordinance, but had shifted in his views after taking office on the Supreme Court, employing immigration restrictionist rhetoric in the majority opinion.[14] Early on, Field noted that nothing in any United States treaty with China was irreconcilable with the Act, but even if it were, Congress could abrogate treaties with foreign nations.[15]

Then Field addressed the power of government over immigration and nationality law, holding for the Court that only the federal government had such power.[15] Field drew heavily upon the language of the law of nations for the majority opinion's proposition that the power to exclude foreigners is "[a]n incident of sovereignty...part of those sovereign powers delegated by the Constitution."[16] However, Field did not originate this proposition for the Court, as European nations had earlier relied upon similar grounds in justification of deportation.[17] Rather, Field reiterated for the Court that foreign affairs powers, under the commerce, naturalization, offenses, and war clauses of the Constitution, implicating the law of nations, permitted wide-ranging immigration restrictions and were largely entrusted to the federal government.[18][19]

After addressing both issues concerning conflict of laws and separation of powers, Field gave broad judicial deference on the matter of immigration and nationality law, stating that such laws were "conclusive upon the judiciary.” In effect, this left to the American people, through Congress and the Presidency, the power over this area of law.[20] This deference, having roots tracing back to the Roman Empire and being reflected, by Founding Fathers such as Gouverneur Morris, during the debates over the Constitution, was first judicially articulated with Field in the majority opinion, before being further developed, over the course of subsequent cases, into the plenary power and consular nonreviewability doctrines in immigration and nationality law.[21]

Aftermath

[edit]Plenary power doctrine

[edit]

The decision in Chae Chan Ping marked a pivotal moment in immigration law and nationality law, as it principally laid the groundwork for the plenary power doctrine. This judicial doctrine states that the federal government has immense and exclusive power over this area of law, so that the substance of such law is insulated from judicial review, largely leaving only procedural due process behind.[23] The result is "a domain where ordinary constitutional rules have never applied".[24] While Chae Chan Ping as a case has received criticism for its racist outcome, the deference afforded by the plenary power doctrine it first articulated has nonetheless mostly persisted and been borne out in 21st century cases such as Trump v. Hawaii (2018).[25] A more recent yet related doctrine to the plenary power doctrine is consular nonreviewability, which holds that actions by consular officials and embassies abroad are generally insulated from judicial review, with few exceptions.[26]

See also

[edit]- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 130

- Illegal immigration to the United States

- Immigration to the United States

- United States nationality law

References

[edit]- ^ "Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations - Office of the Historian". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 16 January 2025. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d Epps, Garrett (20 January 2018). "The Ghost of Chae Chan Ping". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 13 May 2025. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Chin, G. J. (19 May 2005). "Chae Chan Ping and Fong Yue Ting: The Origins of Plenary Power". University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series.

- ^ Legendre, Ray (27 September 2017). "Rewriting Chae Chan Ping". Fordham Law News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2025. Retrieved 9 May 2025.

- ^ Schmitt, Desiree. "The Doctrine of Consular Nonreviewability in the Travel Ban Cases: Kerry v. Din Revisitied". Georgetown University. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ Banks, Angela (1 October 2010). "The Trouble with Treaties: Immigration and Judicial Law". 84 St. John's Law Review 1219-1271 (2010).

- ^ Scott, David (7 November 2008). China and the International System, 1840-1949: Power, Presence, and Perceptions in a Century of Humiliation. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791477427.

- ^ Tracey, Liz (19 May 2022). "The Chinese Exclusion Act: Annotated". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Scott Act (1888)". Harpweek. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Hall, Kermit L. (1999). The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 53. ISBN 9780195139242. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

Scott act 1888.

- ^ Neuman, Gerald (1 January 2006). "On the Adequacy of Direct Review After the REAL ID Act of 2005". NYLS Law Review. 51 (1): 133–158. ISSN 0145-448X.

- ^ Villazor, Rose Cuison (1 January 2015). "Chae Chan Ping v. United States: Immigration as Property". Oklahoma Law Review. 68 (1): 137. ISSN 2473-9111.

- ^ Ayers, Ava (Fall 2004). "International Law as a Tool of Constitutional Interpretation in the Early Immigration Power Cases". Georgetown Immigration Law Review. 19 (1): 125–154 – via SSRN.

The third brief for the government includes a section on international law, which seems to be included in support of the structural argument about the national powers being granted to Congress: 'The whole tenor of the Constitution is that the United States is a nation, and, as to foreign nations and their subjects, is endowed with full sovereign powers.' The following section is entitled 'The law of nations.' Its conclusion, not surprisingly, is that '[i]ntemational law fully establishes the right of a nation to exclude foreigners from its domain." For authority, it cites Chief Justice Marshall in The Schooner Exchange ('The jurisdiction of the nation within its own territory is necessarily exclusive and absolute') and Vattel's Law of Nations ('the lord of the territory may, whenever he thinks proper, forbid its being entered').

- ^ Romero, Victor (1 January 2015). "Elusive Equality: Reflections on Justice Field's Opinions in Chae Chan Ping and Fong Yue Ting". Oklahoma Law Review. 68 (1): 165. ISSN 2473-9111.

- ^ a b Martin, David (1 January 2015). "Why Immigration's Plenary Power Doctrine Endures". Oklahoma Law Review. 68 (1): 29. ISSN 2473-9111.

Justice Field's opinion for the Chae Chan Ping Court invoked sovereignty not to trump rights claims but to solve a federalism problem–structural reasoning that locates the immigration control power squarely in the federal government rather than the states...

- ^ Erman, Sam (1 January 2023). "Status Manipulation in Chae Chan Ping v. United States". Michigan Law Review. 121 (6): 1091–1100. doi:10.36644/mlr.121.6.status. ISSN 0026-2234 – via University of Michigan.

In classic international law accounts, sovereignty was the unlimited, unaccountable, and undivided power of the nation state within its territory and over its nationals...[S]overeignty and the law of nations was everywhere in the Court's decision.

- ^ Hester, Torrie (1 October 2010). ""Protection, Not Punishment": Legislative and Judicial Formation of U.S. Deportation Policy, 1882–1904". Journal of American Ethnic History. 30 (1): 11–36. doi:10.5406/jamerethnhist.30.1.0011. ISSN 0278-5927.

The authority to exclude aliens, the Court found in Chae Chan Ping, is 'an incident of every independent nation. It is a part of its independence.' The Court did not invent the rationale that deportation was a power inherent in sovereignty, nor did it claim the power was uniquely American…In the late nineteenth century, European governments asserted a similar power to remove immigrants.

- ^ Ludsin, Hallie (1 April 2022). "Frozen in Time: The Supreme Court's Outdated, Incoherent Jurisprudence on Congressional Plenary Power over Immigration". North Carolina Journal of International Law. 47 (3): 433.

Notably, the Constitution does not expressly grant the federal government wholesale foreign affairs power. The foreign affairs power, rather, appears to be an amalgamation of Congress's powers to 'regulate commerce with foreign nations, to define offenses against the law of nations, and to declare war'…One more provision rounds out constitutional support for federal immigration powers: the naturalization provision that grants the federal government the power to 'establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization,' or a law for granting naturalized citizenship.

- ^ Natelson, Robert G. (13 November 2022). "The Power to Restrict Immigration and the Original Meaning of the Constitution's Define and Punish Clause". British Journal of American Legal Studies. 11 (2): 209–236. doi:10.2478/bjals-2022-0010.

[Founding era authorities on the law of nations, such as] Pufendorf, Barbeyac, Vattel, Martens, Blackstone, and—more obliquely, Grotius and Burlamaqui— all addressed limits on immigration when writing on the law of nations. These authors consistently recognized the prerogative of governments to impose immigration restrictions. That prerogative was qualified in cases of necessity (for example, a ship being driven by storm onto a foreign shore), and in the cases of exiles and fugitives. As to voluntary immigrants, however, all but Grotius—the earliest of the writers— recognized that the power to restrict was nearly absolute.

- ^ Charles, Patrick (2010). "The Plenary Power Doctrine and the Constitutionality of Ideological Exclusions: An Historical Perspective". Texas Review of Law & Politics. 15 (1): 61–122. ISSN 1098-4577.

- ^ Jake, Stuebner (2024). "Consular Nonreviewability After Department of State v. Munoz: Requiring Factual and Timely Explanations for Visa Denials". Columbia Law Review. Retrieved 9 May 2025.

Stemming from 'ancient principles of the international law of nation-states,' '[t]he power to admit or exclude is a sovereign prerogative.' Indeed, the ability to 'regulate the flow of non-citizens entering the country . . . is an inherent power of any sovereign nation.' This idea traces as far back as the Roman Empire and 'received recognition during the Constitutional Convention.'

- ^ Hurd, Hilary; Schwartz, Yishai (26 June 2018). "The Supreme Court Travel Ban Ruling: A Summary". Lawfare. Archived from the original on 13 May 2025.

- ^ Coutin, Susan; Richland, Justin; Fortin, Véronique (1 March 2014). "Routine Exceptionality: The Plenary Power Doctrine, Immigrants, and the Indigenous Under U.S. Law – UCI Law & Ethnography Lab". Retrieved 13 May 2025.

The plenary power doctrine, established in the 1880s through a series of Supreme Court decisions, thus writes exceptionality into law in a paradoxical way: the judiciary allows government action by exempting such action from judicial review. As a legal doctrine, plenary power is thus authorized by courts through the suspension of their own authority.

- ^ Cox, Adam B. "The Invention of Immigration Exceptionalism". Yale Law School. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ Litman, Leah (26 June 2018). "Opinion | Unchecked Power Is Still Dangerous No Matter What the Court Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

The section of the opinion [in Trump v. Hawaii] rejecting the plaintiffs' First Amendment claim began with an explanation about why the entry-ban case differs from other First Amendment challenges. The difference, the court said, is that 'the admission and exclusion of foreign nations is a fundamental sovereign attribute exercised by the Government's political departments largely immune from judicial control.' The court quoted a passage from a prior case that relied on both [Chae Chan Ping] and Fong Yue Ting to justify the idea that immigration is insulated from judicial review.

- ^ Johnson, Kevin (18 February 2015). "Argument preview: The doctrine of consular non-reviewability historical relic or good law?". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 9 May 2025.

External links

[edit]- Text of Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist

- United States Supreme Court cases

- United States Supreme Court cases of the Fuller Court

- United States immigration and naturalization case law

- 1889 in United States case law

- Deportation from the United States

- China–United States relations

- Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

- Chinese-American culture in San Francisco